2025 Study Architecture Student Showcase - Part XIII

Sustainability takes the spotlight in today’s edition of the 2025 Study Architecture Student Showcase. In Part VIII, we take a look at projects that incorporate sustainable practices to combat climate change while supporting local communities. The featured strategies include intentional material selection, environmental analyses, integrating ecological preservation, daylighting, holistic integration, natural ventilation systems, regenerative design principles, and more.

Scroll down for a closer look and get a glimpse at the future of green design practices!

V.L.A.B. Innovation Center by Nadiia Rudenko, Ryan Choucair & Zaynab Alhisnawi, M.Arch ’25

University of Detroit Mercy | Advisors James Leach & Kristin Nelson

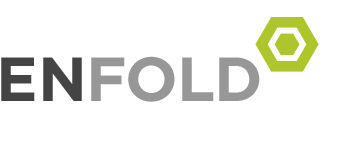

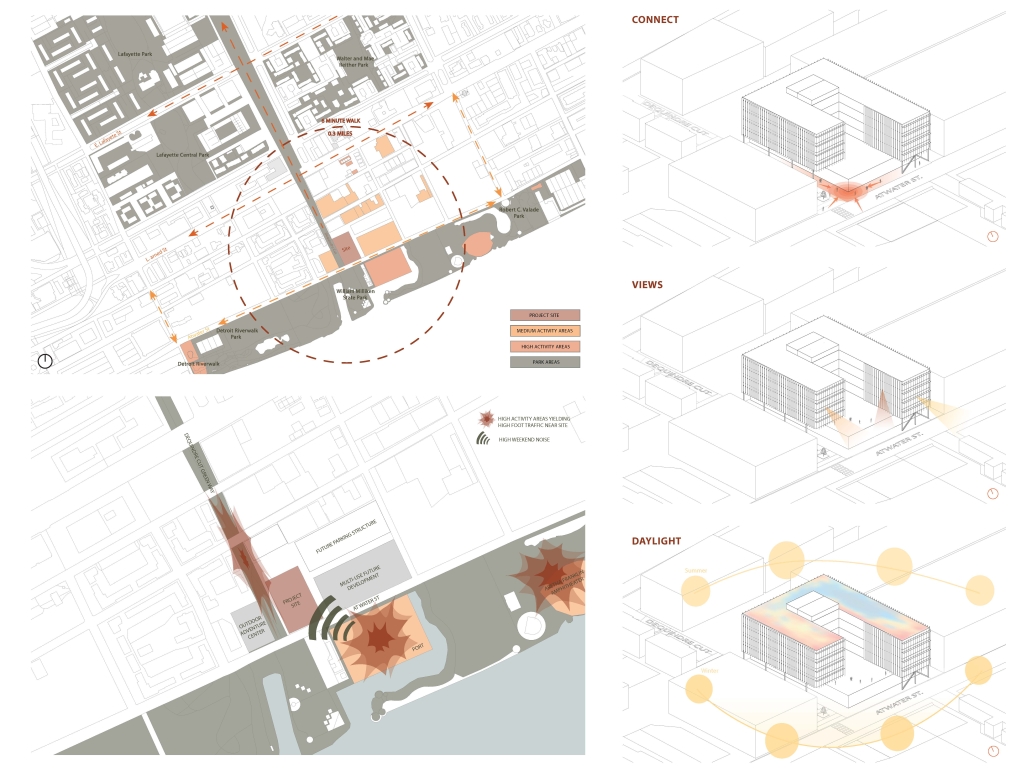

The Innovation Lab was designed with three primary objectives: to foster connectivity, enhance experiential qualities, and create a highly sustainable building. Our design process was guided by extensive research, incorporating qualitative, secondary, and applied methodologies.

We began with qualitative observational research, conducting on-site visits to analyze the existing environmental conditions, pedestrian flow, and spatial characteristics. This initial study helped us understand how users currently interact with the site and informed our approach to improving connectivity and engagement.

As the project progressed, we conducted secondary research to evaluate critical factors such as climate, infrastructure, and energy efficiency. Understanding Detroit’s climate, seasonal variations, and sustainability challenges allowed us to make informed decisions about material selection, glazing optimization, and shading strategies. To ensure the building’s energy performance was efficient, we used applied research, testing both passive and active systems to optimize thermal comfort, daylighting, and energy use intensity (EUI).

One of our key design achievements was creating a space that strengthens the relationship between the interior and exterior experience of the building. Strategically, we established a welcoming atmosphere where people outside feel invited in, and those inside remain connected to their surroundings.

We utilized cove.tool, a data-driven simulation platform that allowed us to refine our design through environmental analysis and energy modeling. Ultimately, our research-driven approach led to a building that successfully embodies our core design principles.

Instagram: @zaynab_alhisnawi

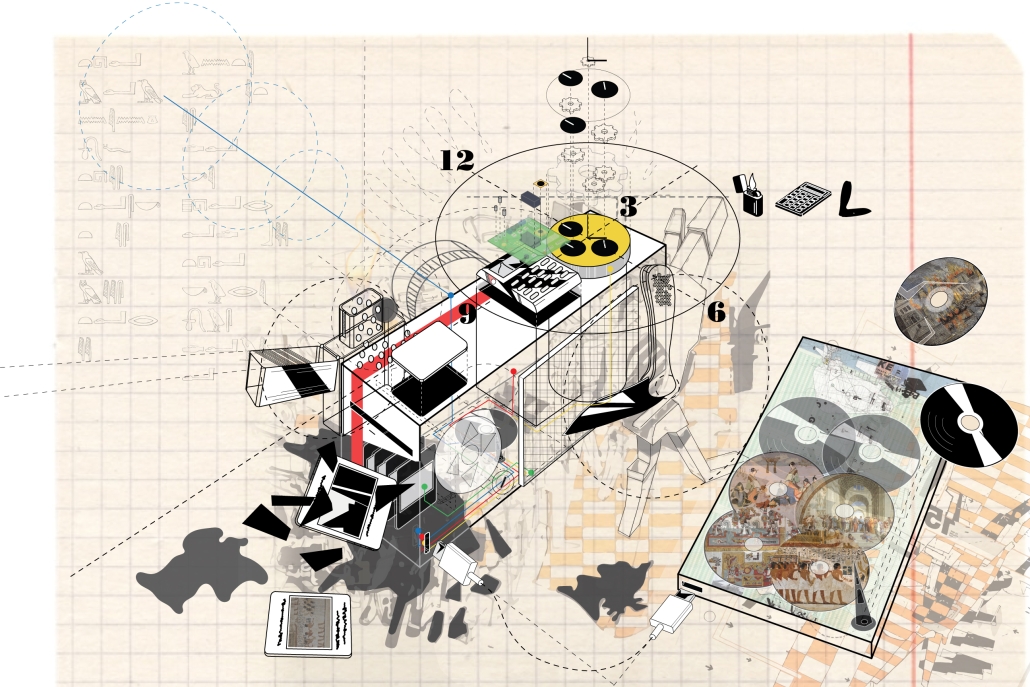

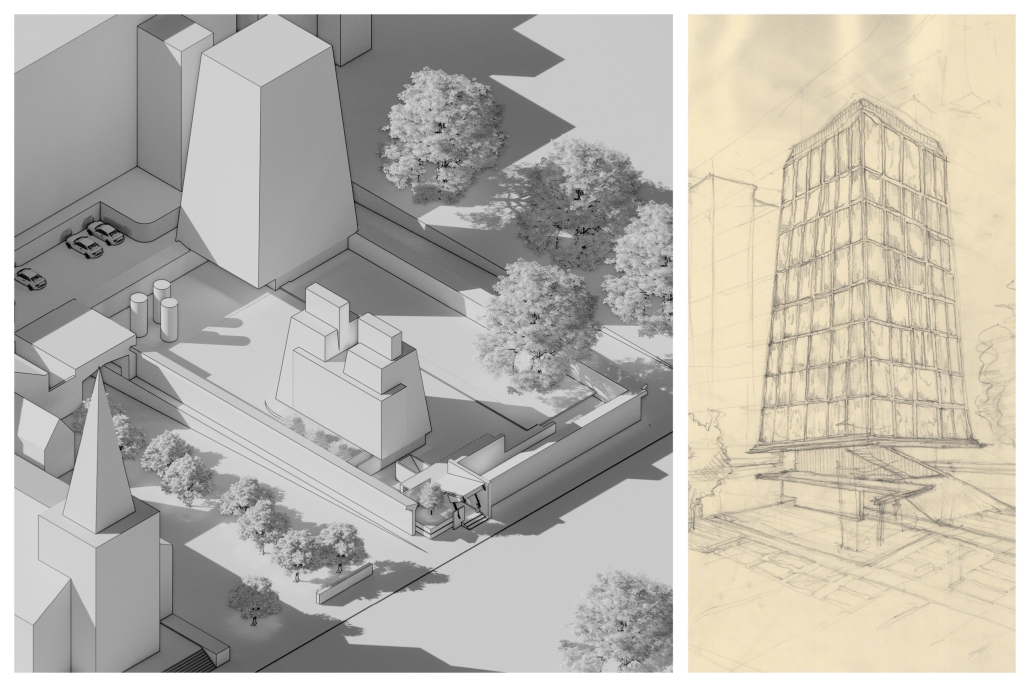

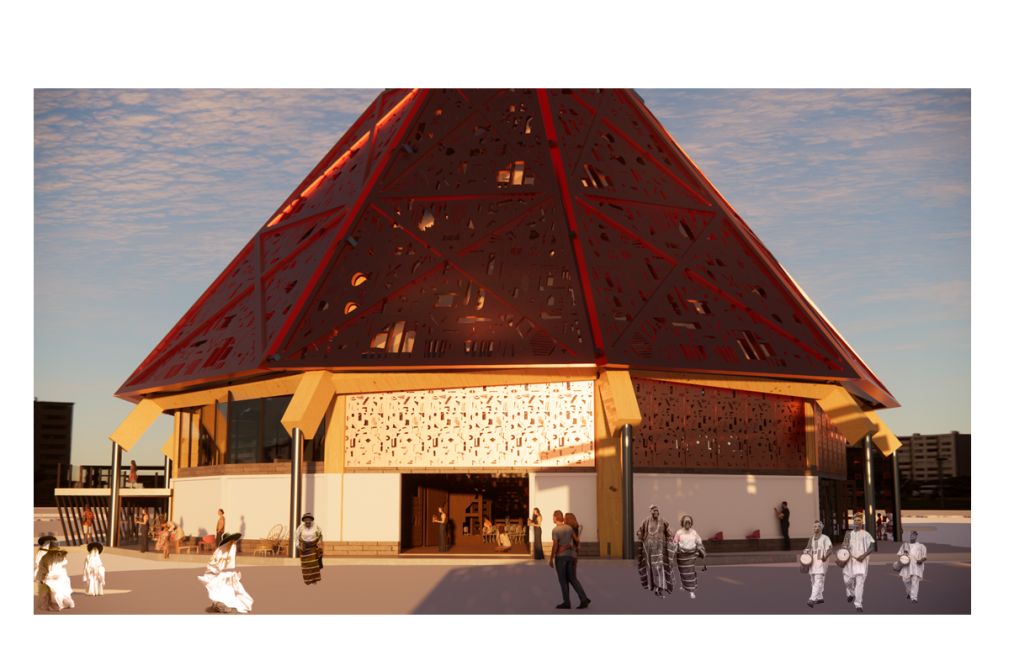

Falling Stars Protocol by Adeniyi Onanuga, B.Arch ‘25

Drexel University | Advisor: Wolfram Arendt

“The Falling Stars Protocol” proposes solutions to climate disasters by using biomimicry and climate science to analyze current weather and environment trends, protect endangered biomes, support community-driven ecological stewardship, and advocate for multilateral climate action legislation.

By leveraging natural systems, representation, and education strategies accessible to all – including local communities, scientists, and tourists – this framework emphasizes active recovery and resilience rather than passive preservation.

Though the framework does not always call for architectural solutions, this prototypical implementation addresses potential Biodiversity Loss in the Cape Floristic Region of South Africa through a botanical research campus and tourism-centric living collections.

This project was nominated for the Michael Pearson Award.

Instagram: @neonanuga, @drexel.architecture

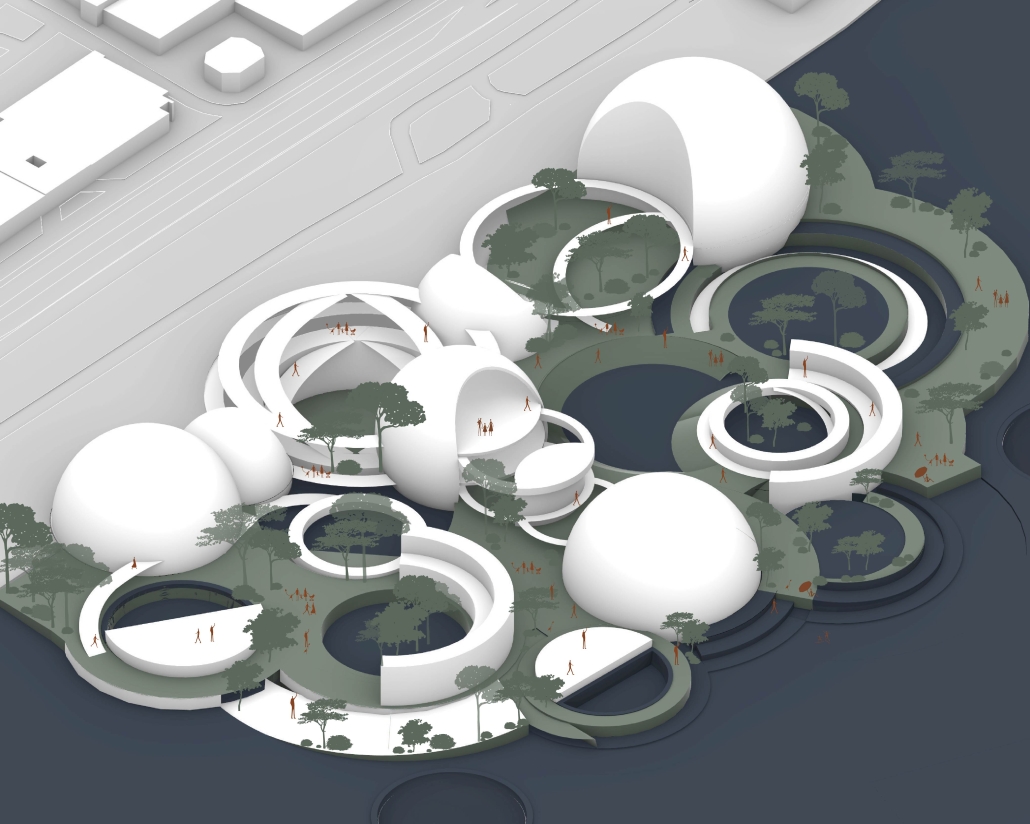

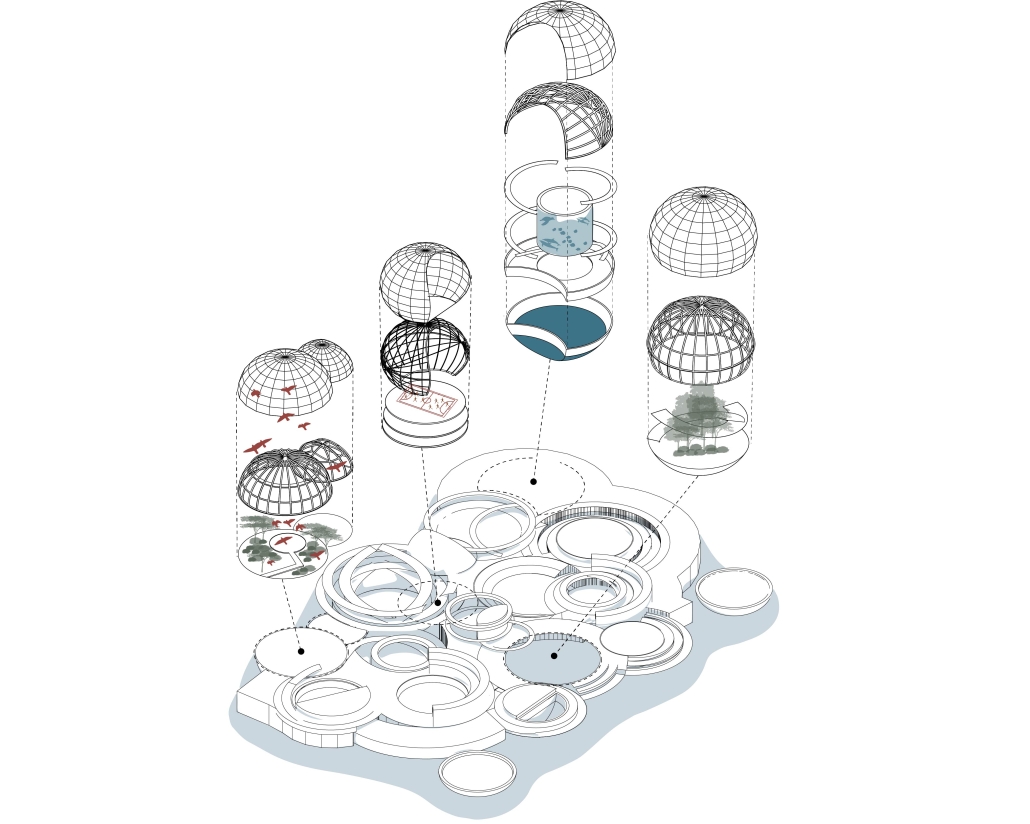

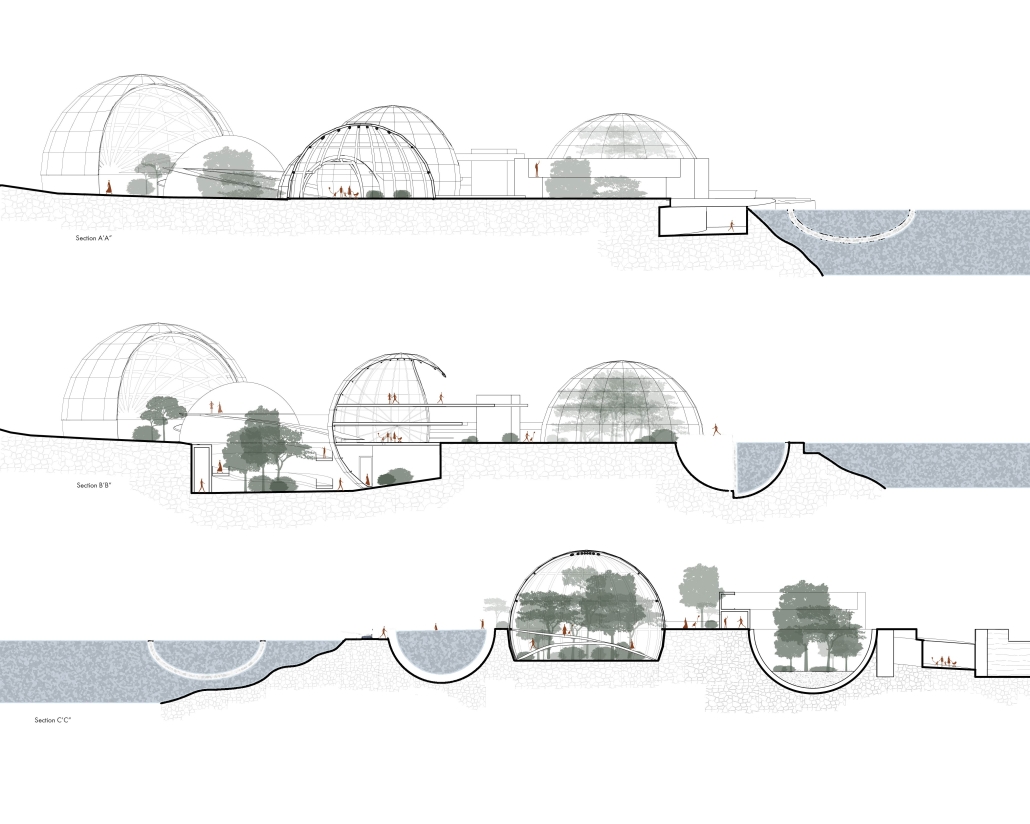

EcoScape: When Nature and Culture Converge by Nadia Bryson & Fairy Patel, M.Arch ’25

New York Institute of Technology | Advisors: Marcella del Signore & Evan Shieh

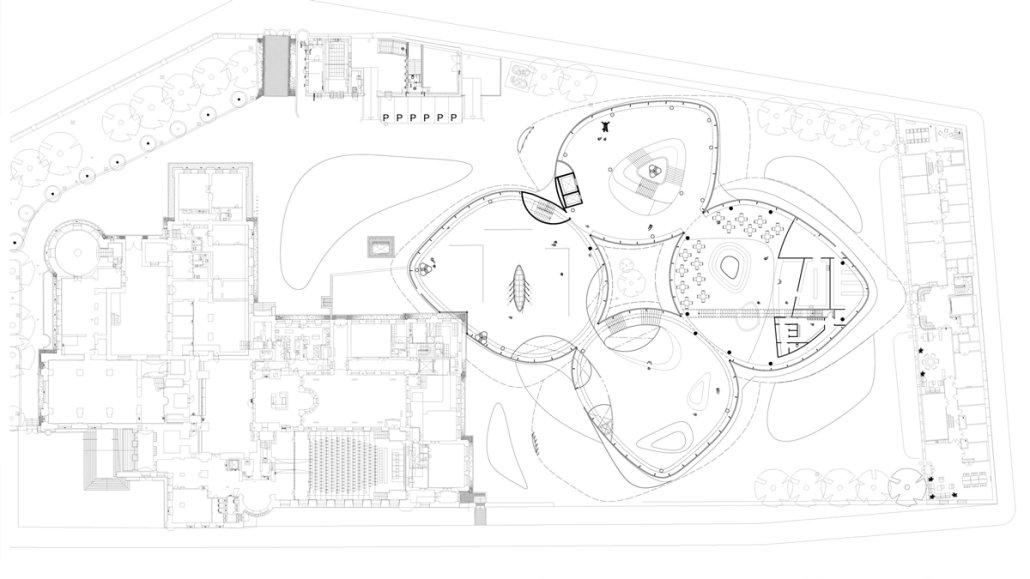

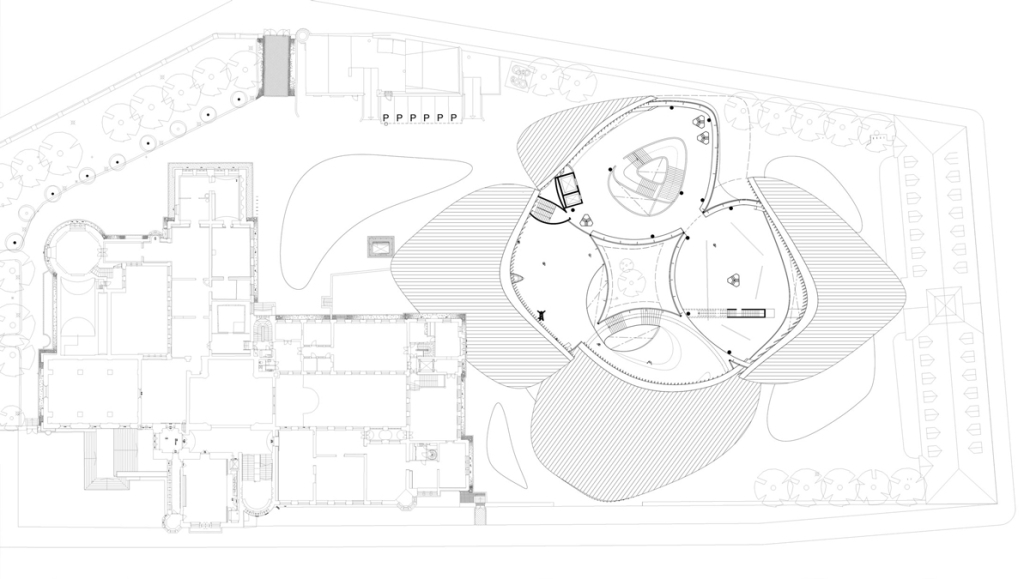

“EcoScape” is a sustainable architectural proposal that reimagines tourism in Rio de Janeiro by integrating ecological preservation, cultural heritage, and urban development. Responding to the environmental degradation caused by mass tourism and industrialization, the project proposes a green infrastructure network that connects natural, cultural, and recreational spaces throughout the city. Inspired by the Eden Project, EcoScape merges immersive biomes—such as rainforest, aquatic environments, butterfly sanctuaries, and wetlands—with educational and public spaces designed to foster environmental awareness and biodiversity conservation.

The proposal is grounded in a historical timeline of Rio’s environmental transformation, from the sustainable practices of Indigenous communities like the Tupi and Guarani, through colonial exploitation and industrial expansion, to the present-day shift toward ecological recovery. Over the centuries, deforestation, resource extraction, and urban sprawl have replaced natural habitats and strained ecosystems. EcoScape responds to this legacy by restoring ecological balance, promoting green corridors, and introducing community-focused tourism that prioritizes education and sustainability.

The spatial design follows a progression from compact cores to open, connected networks. Circulation rings, transitional nodes, and elevated pathways allow for seamless visitor flow while preserving natural terrain. Zones are designated for specific types of tourism—beach, cultural, eco-adventure, festival, and sports—with modular structures like open-air pavilions, courtyards, and arenas accommodating various activities.

Stakeholder engagement is central to the design, involving local communities, governments, researchers, and tourists in the stewardship of Rio’s ecological and cultural assets. The site functions as a hybrid of a public attraction and an environmental research center.

Ultimately, EcoScape envisions a future where nature is not merely a backdrop to tourism, but the primary experience. It transforms Rio into a living landscape where ecological awareness, cultural celebration, and sustainable development converge, inviting visitors to become participants in preservation rather than passive consumers.

Instagram: @blanca_nieves123, @fairy_5828, @ev07, @marcelladelsi

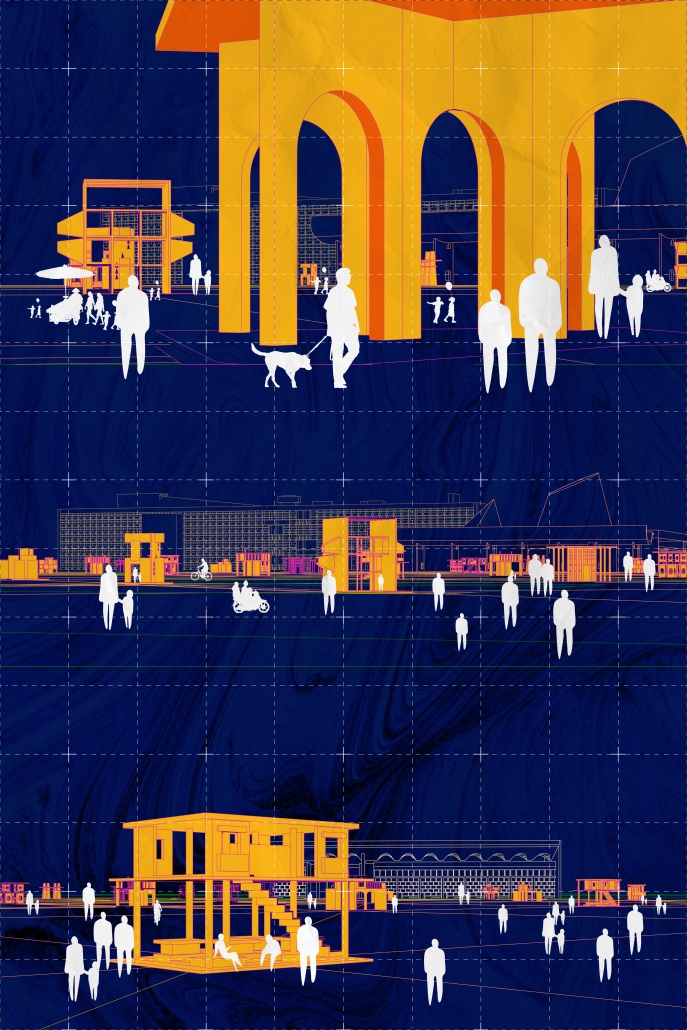

Water Comes First – “Enhancing lifelong cities as culture endures” by Bruno Antonio Remis Estrada, Melina Guajardo Gaytán, Edgar Jhovany Ochoa Ángeles, María Fernanda Felix González & Brenda Lizeth Ortega Villalobos, B.Arch ’25

Tecnológico de Monterrey | Advisors: Juan Carlos López Amador, Roberto García Rosales & Rodolfo Manuel Barragán Delgado

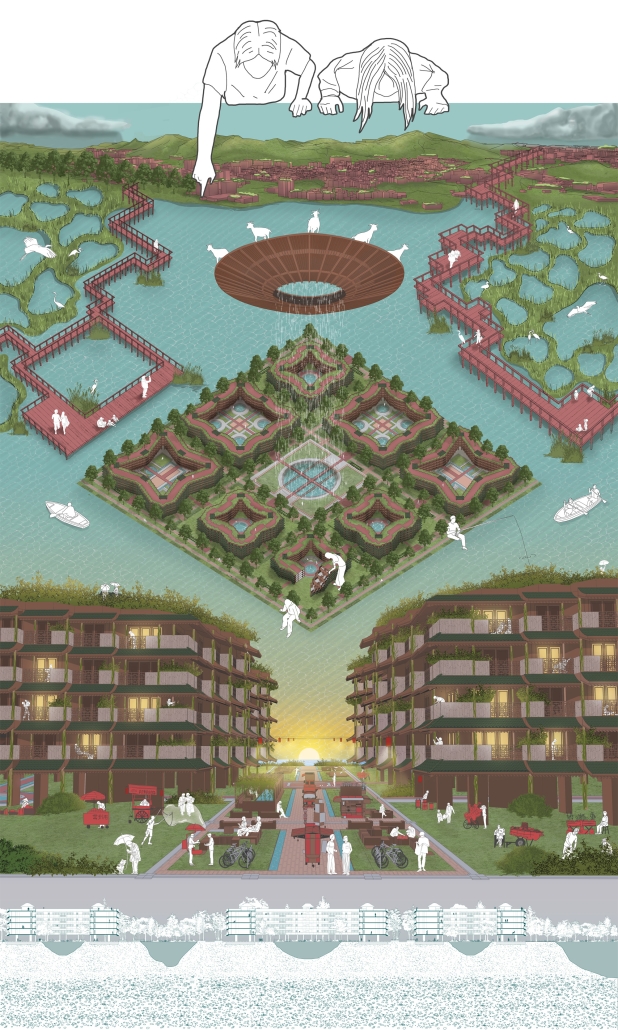

“Water Comes First” addresses the ecological and urban challenges faced by Changzhou Island in Guangzhou, including insufficient infrastructure, frequent flooding, and population decline. As part of the city’s 100 km waterfront development plan, the proposal confronts climate change-induced flooding through a nature-based strategy. Rather than treating water as a threat, it is embraced as a vital, dynamic force. The project envisions urban development as an adaptive system that works with natural water cycles while supporting social, cultural, and infrastructural growth.

At the heart of the proposal is a 250-meter territorial grid overlaying the island, serving as a spatial and strategic guide for interventions in mobility, hydrology, and landscape. Nine tailored Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) are integrated into this framework, including rainwater harvesting, percolation wells, wetlands, bio-filtration zones, and permeable surfaces. These are designed not as isolated fixes, but as interconnected elements of a holistic water management system.

A new multimodal transportation hub is proposed to connect the island to the broader Guangzhou region. This hub supports sustainable mobility—walking, cycling, and public transport—reducing car dependency and improving accessibility. Community spaces, such as a Pearl River research center and public plazas, further reinforce the island’s social and ecological resilience.

“Water Comes First” offers a flexible, replicable model for other flood-prone or low-lying areas. It prioritizes the preservation of natural ecosystems as a key component of resilience, ensuring urban infrastructure works in harmony with hydrological cycles. By maintaining the balance between rainfall and underground aquifers, the project safeguards both the environment and the built environment.

Ultimately, the proposal reframes climate change not as a threat to be resisted, but as a condition to be intelligently addressed. It creates a resilient landscape that connects people, culture, and nature—embracing water as a catalyst for regeneration.

This project was exhibited at Designing Resilience Global, 2025.

Instagram: @bro__remis, @melina_guajardo, @_fernandafelix_, @brendrafts, @jhovany_8a, @eaad.mty, @saarq_itesm, @arqtecdemty

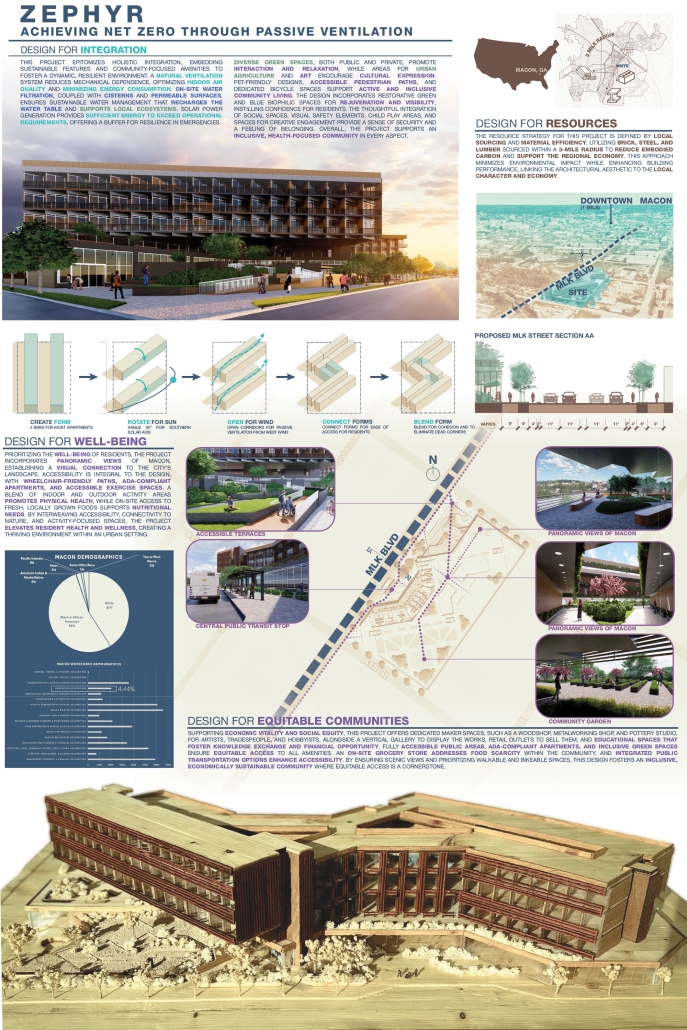

ZEPHYR: ACHIEVING NET ZERO THROUGH PASSIVE VENTILATION by Maya Schiltz & Owen Phillips, B.Arch ’25

Kennesaw State University | Advisor: Robin Puttock

This project epitomizes holistic integration, embedding sustainable features and community-focused amenities to foster a dynamic, resilient environment. A natural ventilation system reduces mechanical dependence, optimizing indoor air quality and minimizing energy consumption. on-site water filtration, coupled with cisterns and permeable surfaces, ensures sustainable water management that recharges the water table and supports local ecosystems. Solar power generation provides sufficient energy to exceed operational requirements, offering a buffer for resilience in emergencies. Diverse green spaces, both public and private, promote interaction and relaxation, while areas for urban agriculture and art encourage cultural expression. Pet-friendly designs, accessible pedestrian paths, and dedicated bicycle spaces support active and inclusive community living. The design incorporates restorative green and blue biophilic spaces for rejuvenation and visibility, instilling confidence for residents. The thoughtful integration of social spaces, visual safety elements, child play areas, and spaces for creative engagement provides a sense of security and a feeling of belonging. Overall, the project supports an inclusive, health-focused community in every aspect.

This project was presented at the 2025 Biophilic Leadership Summit.

Instagram: @owen_p02, @mayaschiltz, @robinzputtock

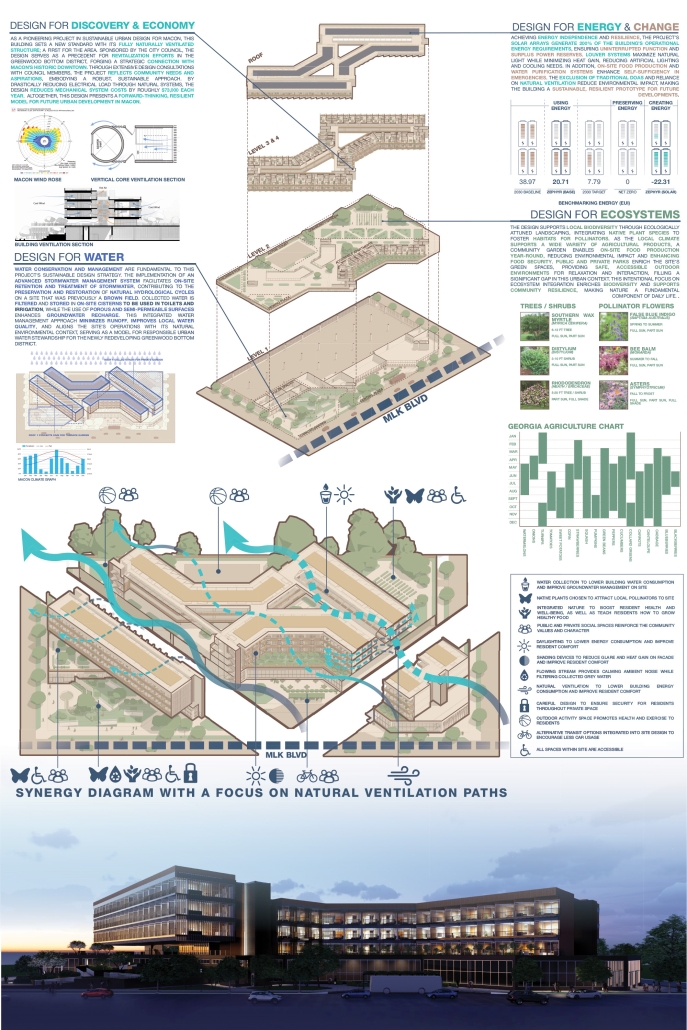

ECO₂ Research Center – Carbon Emissions’ Impact: The Role of Architecture and Technology in Living Environments by Marisela López-Rivera, B.Arch ’25

Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico | Advisors: Jesús O. García-Beauchamp, Pilarín Ferrer-Viscasillas & Pedro A. Rosario-Torres

Climate change is a critical challenge of the XXI century, driven largely by carbon dioxide emissions that create a porous blanket over Earth’s atmosphere, trapping heat and accelerating global warming. “Carbon Emissions’ Impact: The Role of Architecture and Technology in Living Environments” states that a large portion of carbon dioxide emissions originates from building development and operations, while also raising the question: How can architecture and technology adapt to address this issue?

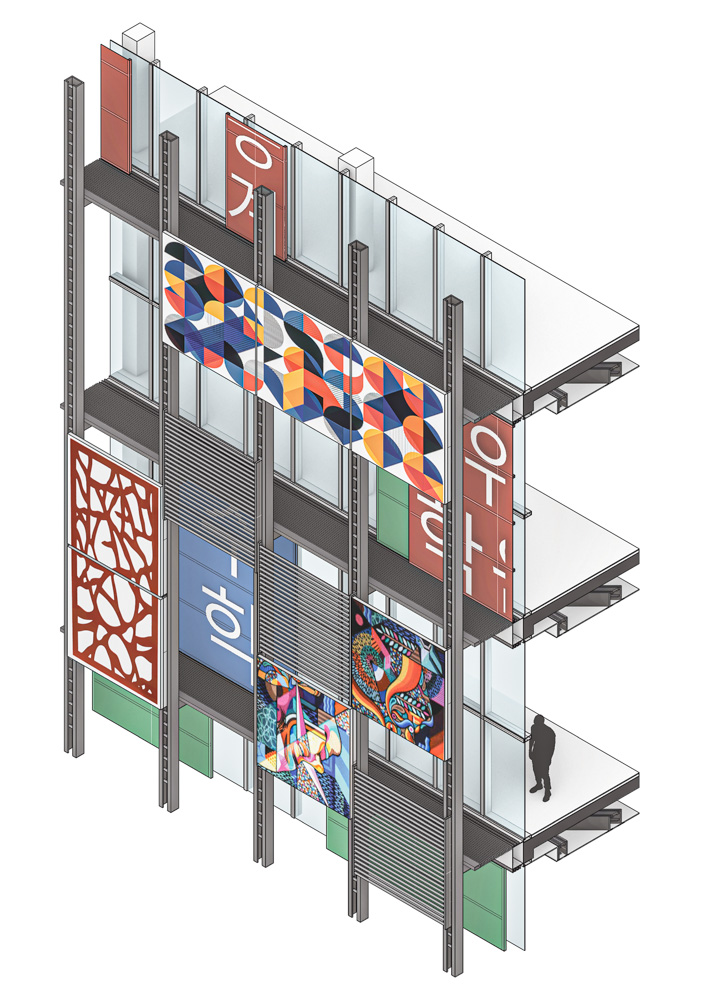

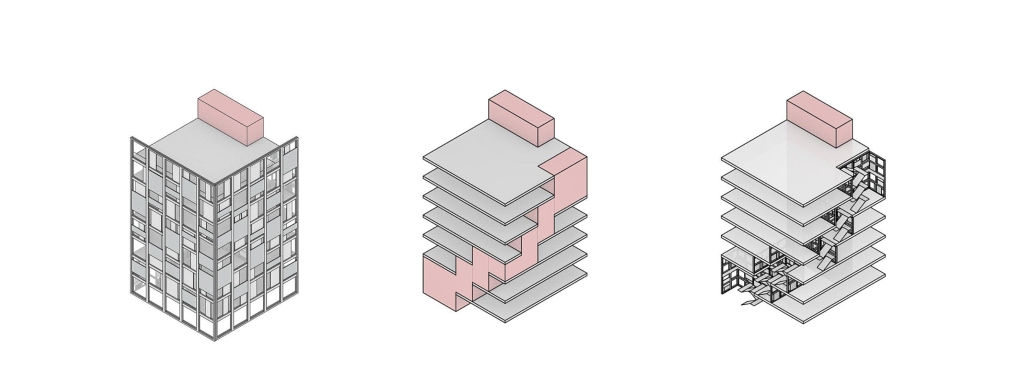

The proposal, titled “ECO₂ Research Center,” envisions a facility that unites climate advocates, including scientists and Generation Z university students, to form an “experimental community” centered on sustainability, education, research, and professional development grounded in the principle of “ecological awareness.” Located in Santurce, a densely populated urban area within the capital of San Juan, Puerto Rico, the site was chosen for its existing infrastructure, including the 1924 “Edificio Yaucono” and two additional structures on the northeast corner. This characteristic reflects on adaptive reuse, aligned with the circular carbon economy, reducing embodied carbon emissions by conserving and restoring existing buildings and creating a dialogue with new additions, such as design articulations that distinguish the original structure and the new residential building sitting on top of the “Edificio Yaucono.” The building’s massing centers around a “green community atrium” that connects local and experimental communities. Through “structural fragmentation,” the design creates sky gardens, terraces, and double-height spaces that break volumetric uniformity. Enhancing environmental performance and emphasizing the interconnectedness between humans, non-humans, and technology, the building employs a design strategy called “green blanket,” featuring green facades and green roofs integrated into the building. Additionally, a black aluminum brise soleil, referred to as the “porous blanket,” provides solar protection and ventilation while symbolizing the enduring presence of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

By rejuvenating what is already present, architecture can serve as a restorative force that addresses carbon emissions and climate change while respecting history and place instead of contributing to destruction.

Instagram: @arch.m.chela

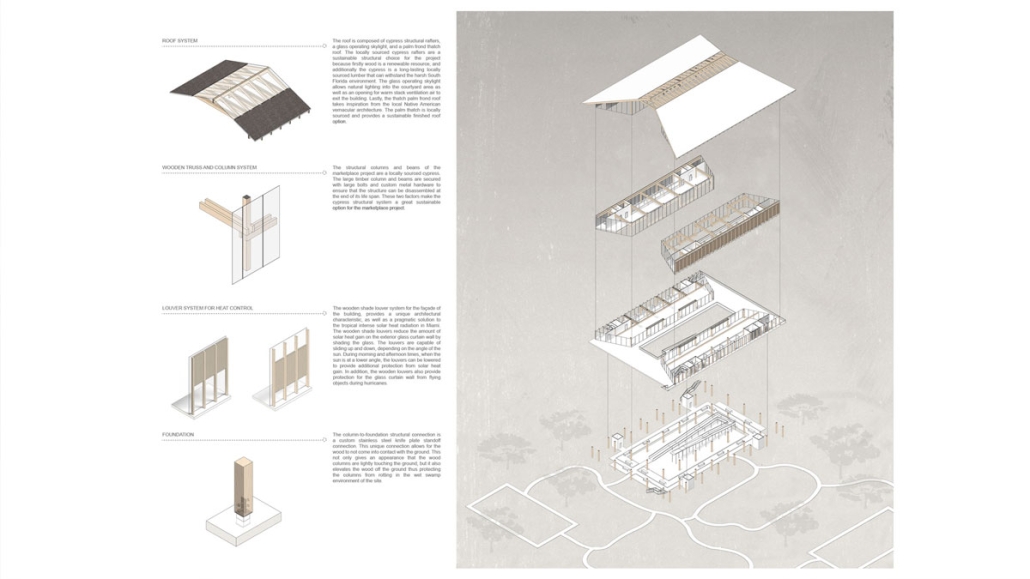

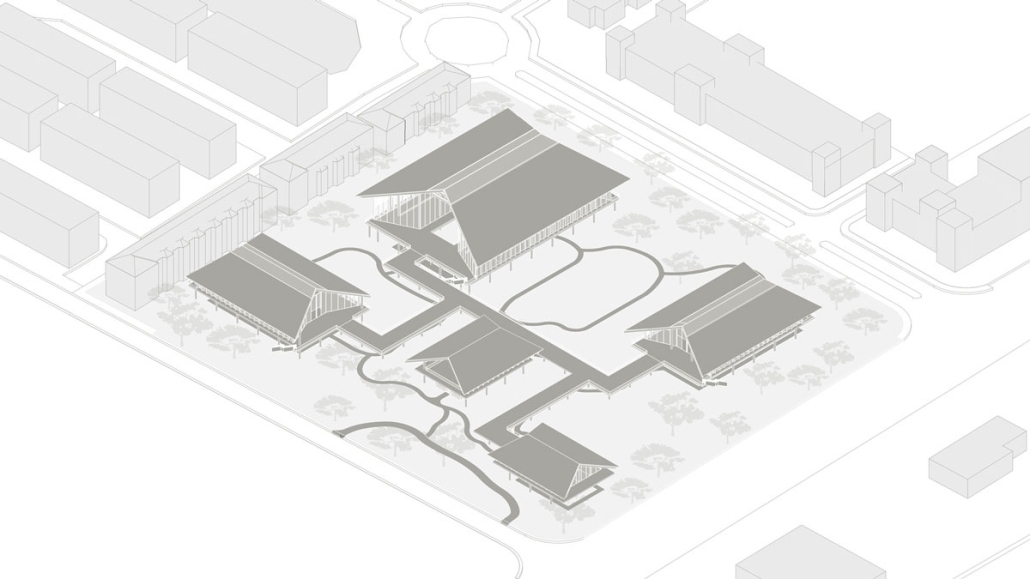

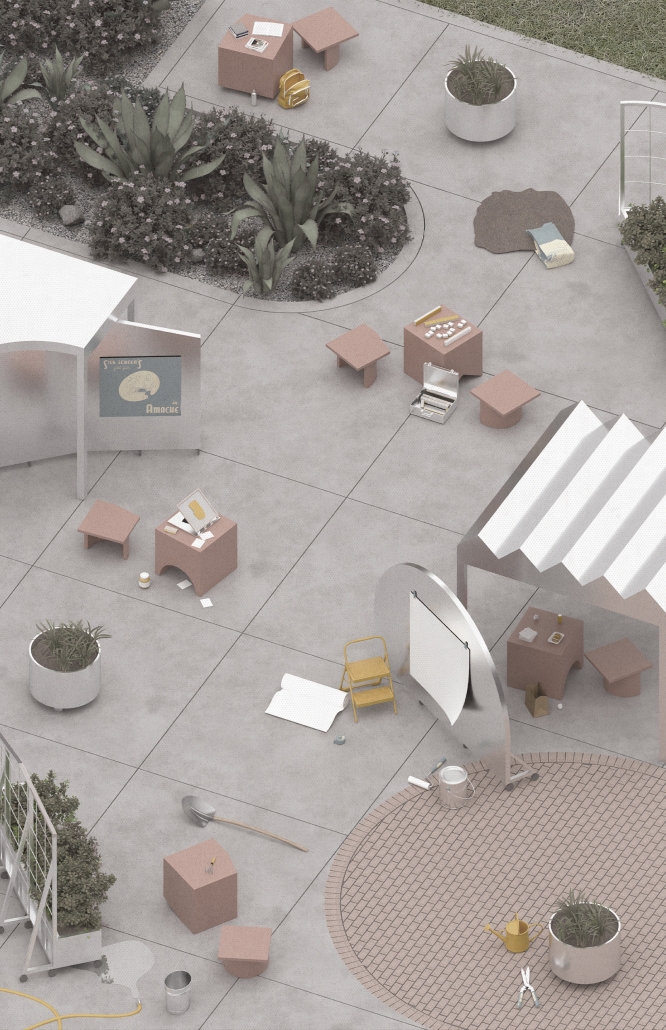

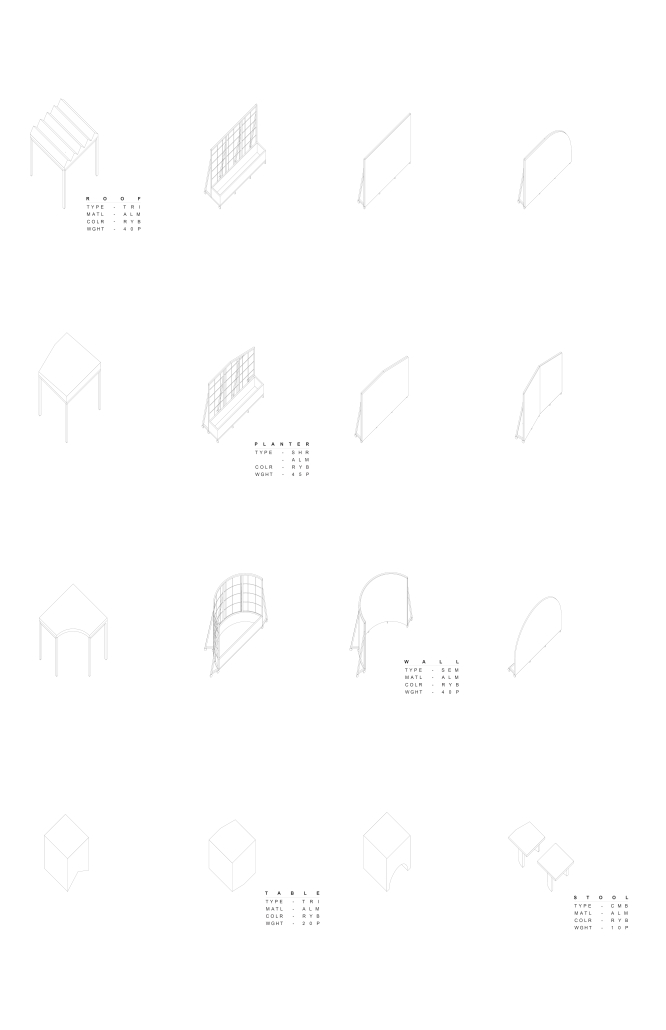

Everglades Market by Stefan Underwood, M.Arch ’25

Academy of Art University | Advisor: Aurgho Jyoti

With modern farming practices, humans have created a divide between agriculture, suburban, urban, and protected land. These boundaries have caused numerous challenges that far outweigh the benefits. South Florida and the region’s fragile ecology are a perfect case study that represents the global challenges we face locally. The boundaries created need to be reanalyzed and applied more traditionally, where all regions sustainably coexist. Traditional cultures, such as the South Florida Native Americans, have successfully blended the three regions and blurred the boundaries between agriculture, nature, and urban. By taking inspiration from Native American architecture, the “Everglades Market” creates a model in which all three regions can survive together through agriculture.

This project received the Academy of Art University M.Arch Thesis Award.

Instagram: @aur.architecture

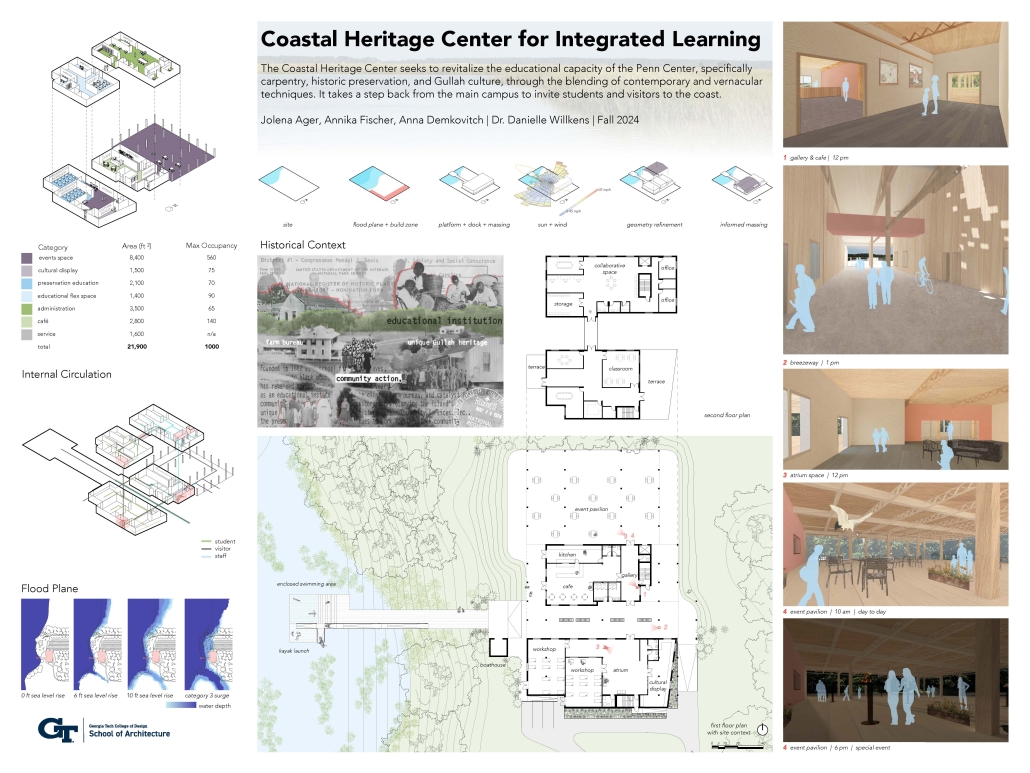

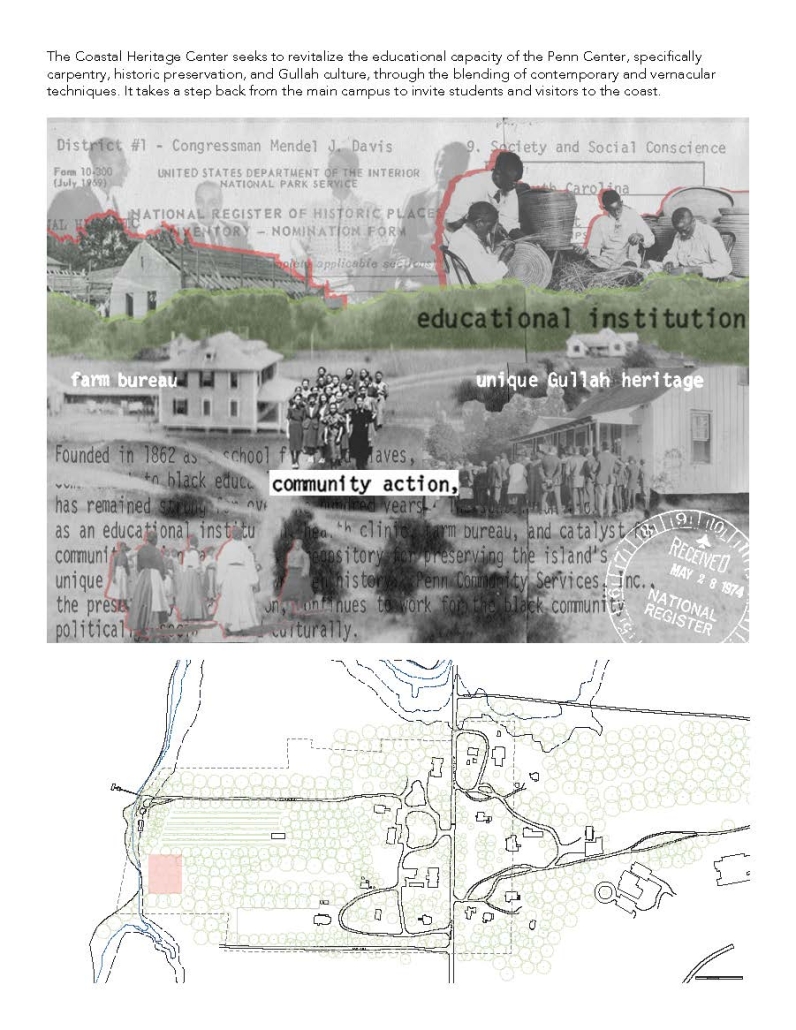

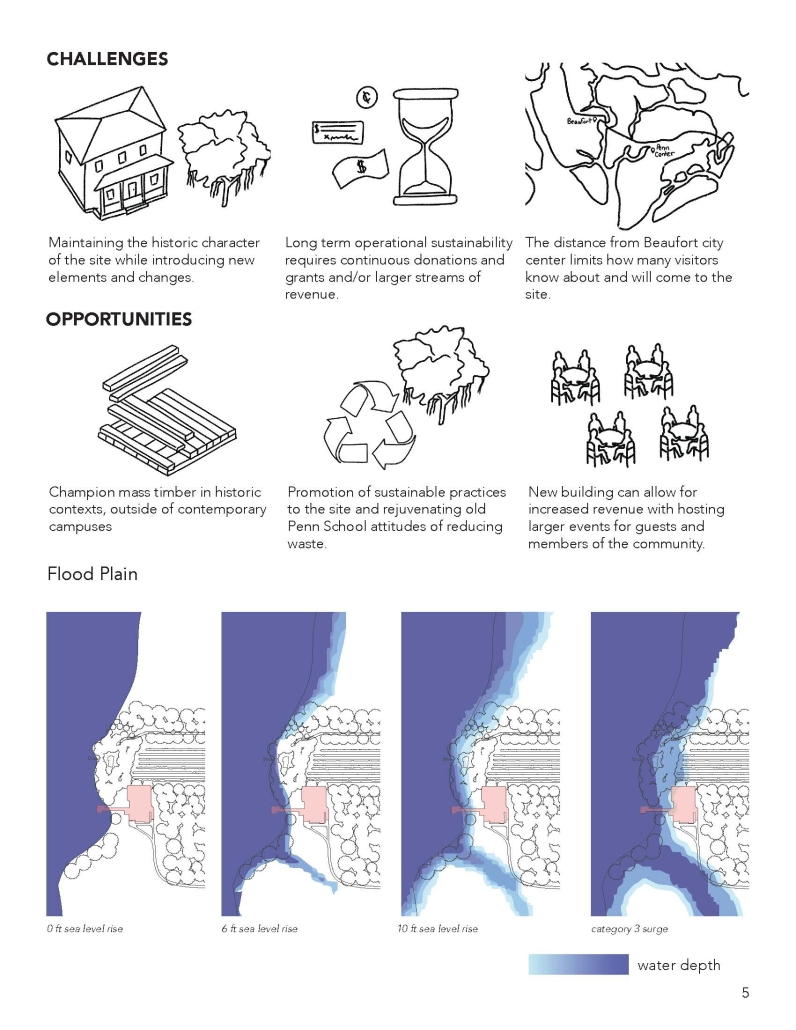

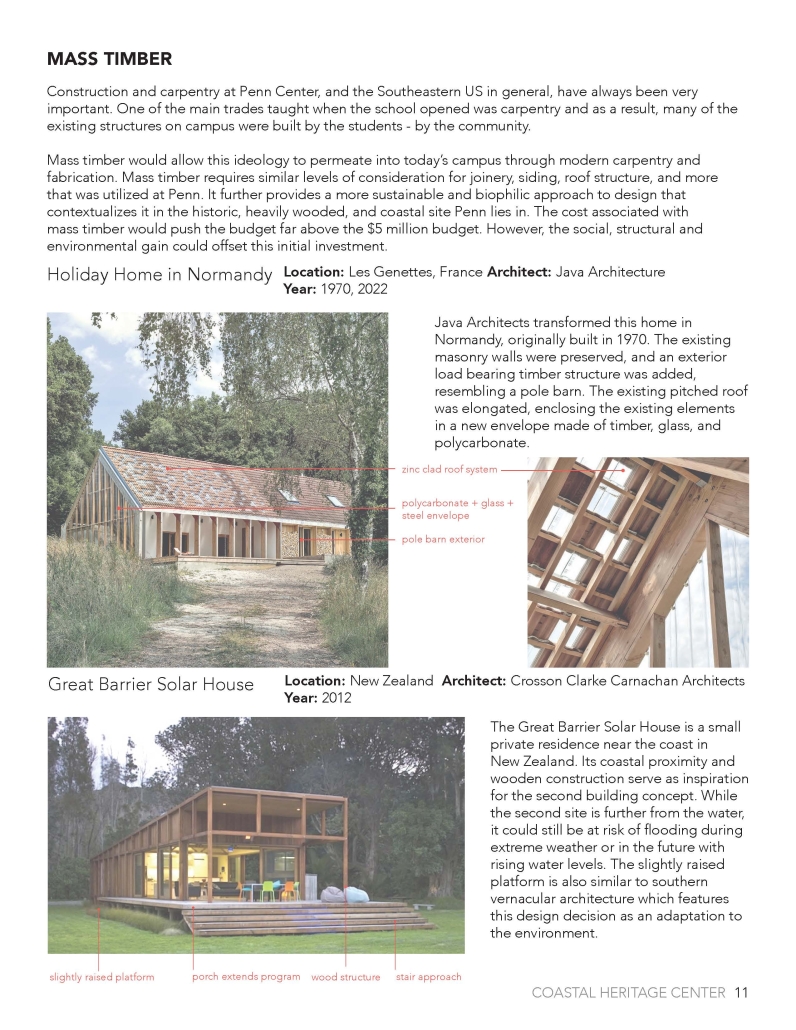

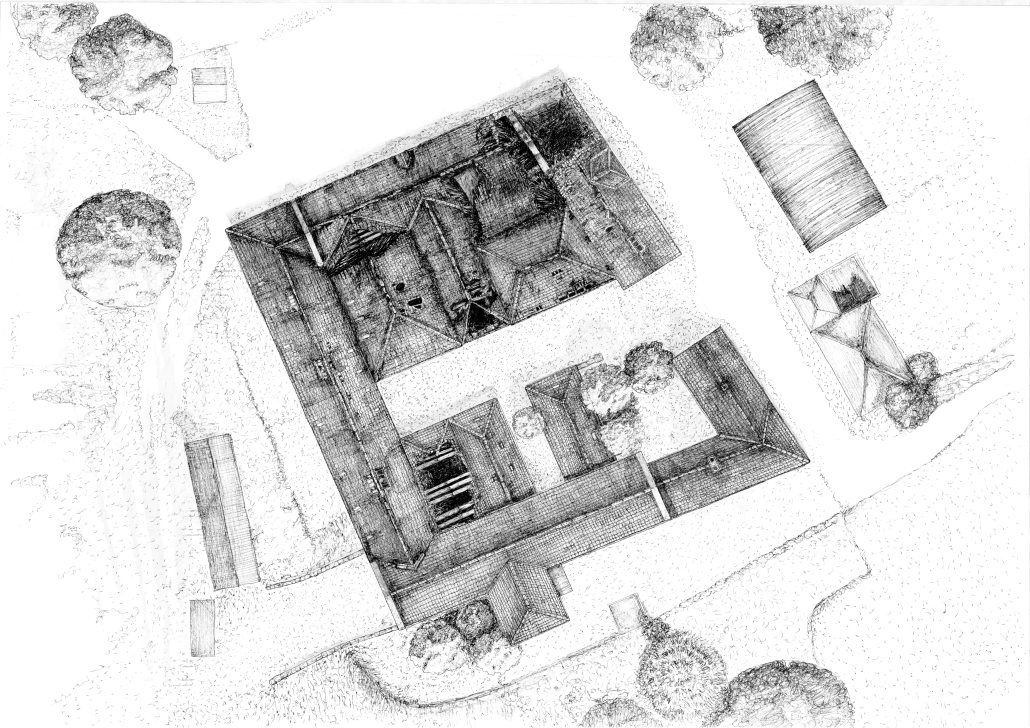

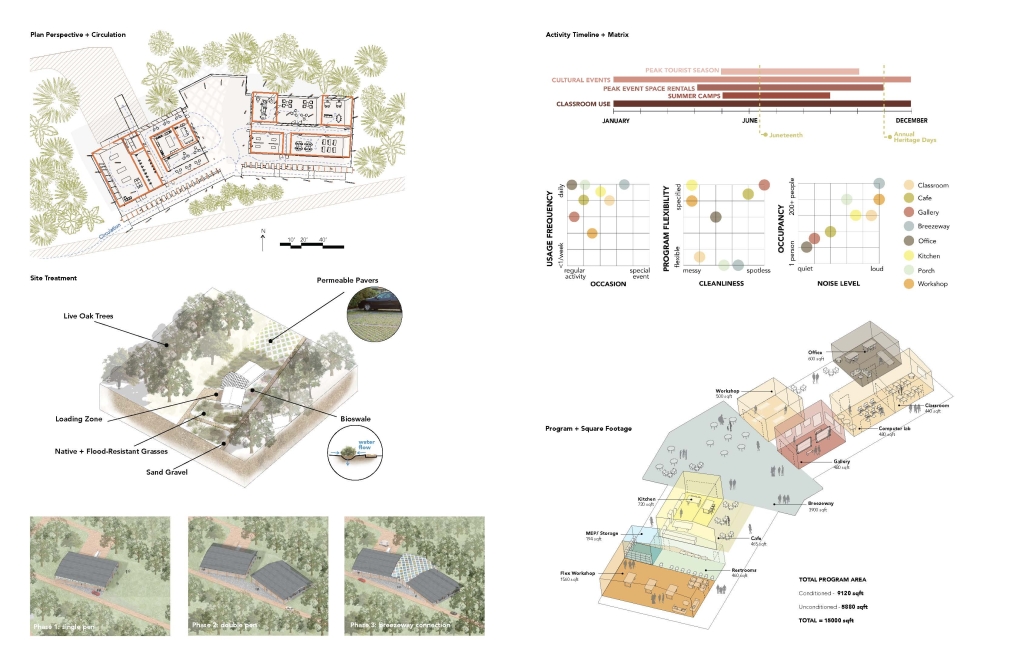

COASTAL HERITAGE CENTER FOR INTEGRATED LEARNING by Jolena Ager, Anna Demkovitch & Annika Fischer, BS in Architecture ’25

Georgia Tech | Advisor: Danielle Willkens

The Coastal Heritage Center seeks to revitalize the educational capacity of the Penn Center, specifically carpentry, historic preservation, and Gullah culture, through the blending of contemporary and vernacular techniques. It takes a step back from the main campus to invite students and visitors to the coast. Construction and carpentry at Penn Center, and the Southeastern U.S. in general, have always been very important. One of the main trades taught when the school opened was carpentry, and as a result, many of the existing structures on campus were built by the students – by the community. Mass timber would allow this ideology to permeate into today’s campus through modern carpentry and fabrication. Mass timber requires similar levels of consideration for joinery, siding, roof structure, and more that was utilized at Penn. It further provides a more sustainable and biophilic approach to design that contextualizes it in the historic, heavily wooded, and coastal site Penn lies in. The cost associated with mass timber would push the budget far above the $5 million budget. However, the social, structural, and environmental gains could offset this initial investment.

At the start of the semester, the Live Oak Studio had the opportunity to visit the Penn Center for a five-day-long field study experience. During that time, our cohort absorbed St. Helena’s flora and fauna as well as the captivating history of Gullah Geechee heritage. Instead of a traditional architectural review, our studio presented our semester’s work to the community of St. Helena and those involved at the Penn Center. Insights from the local residents were particularly generative for conversations about the future needs of the Penn Center, coastal resiliency on St. Helena Island, and the benefits of mass timber construction.

This project won the GT Dagmar Epsten Prize.

Instagram: @demkovitchdesign, @archDSW, @georgiatech.arch

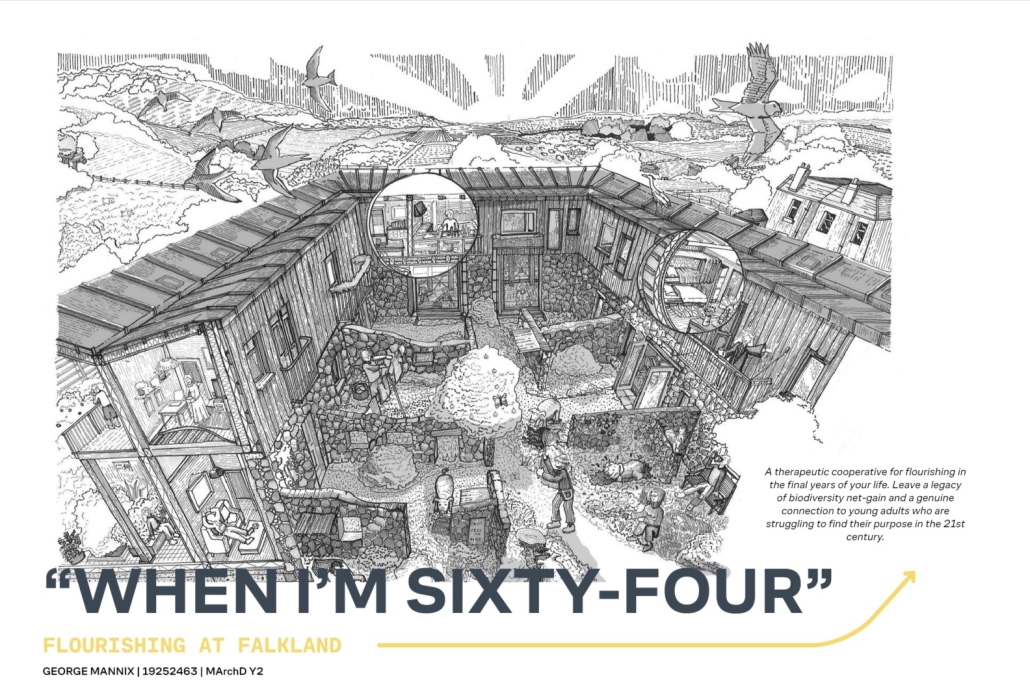

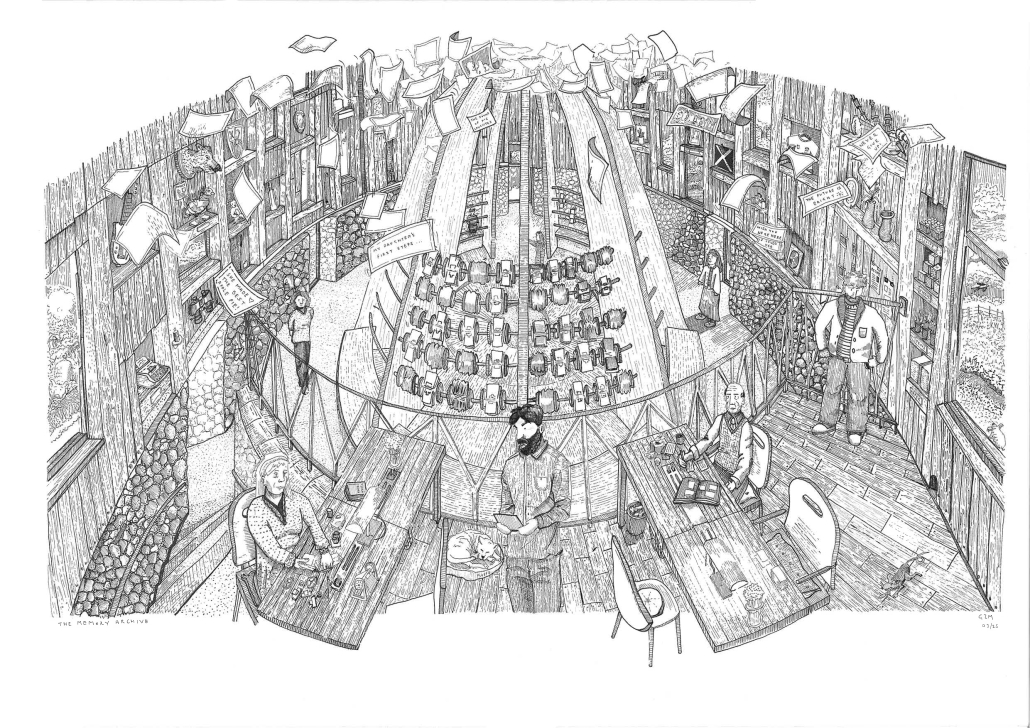

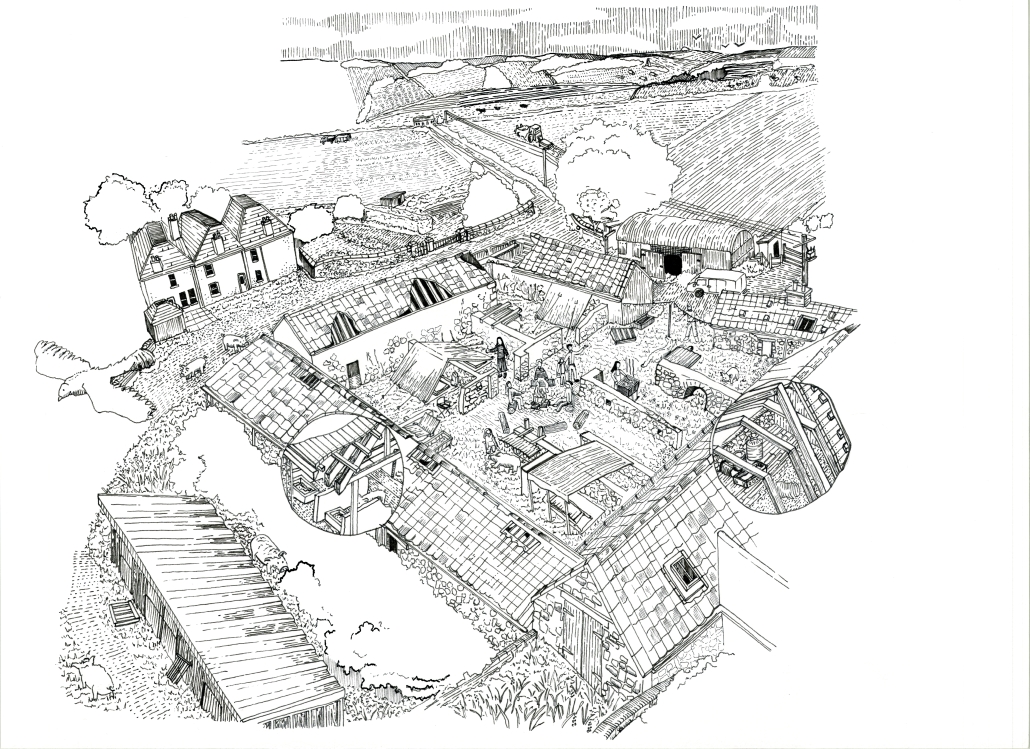

The Watershed Collective by Jasmin Solaymantash, M.ArchD ’25

Oxford Brookes University | Advisors: Melissa Kinnear & Alex Towler

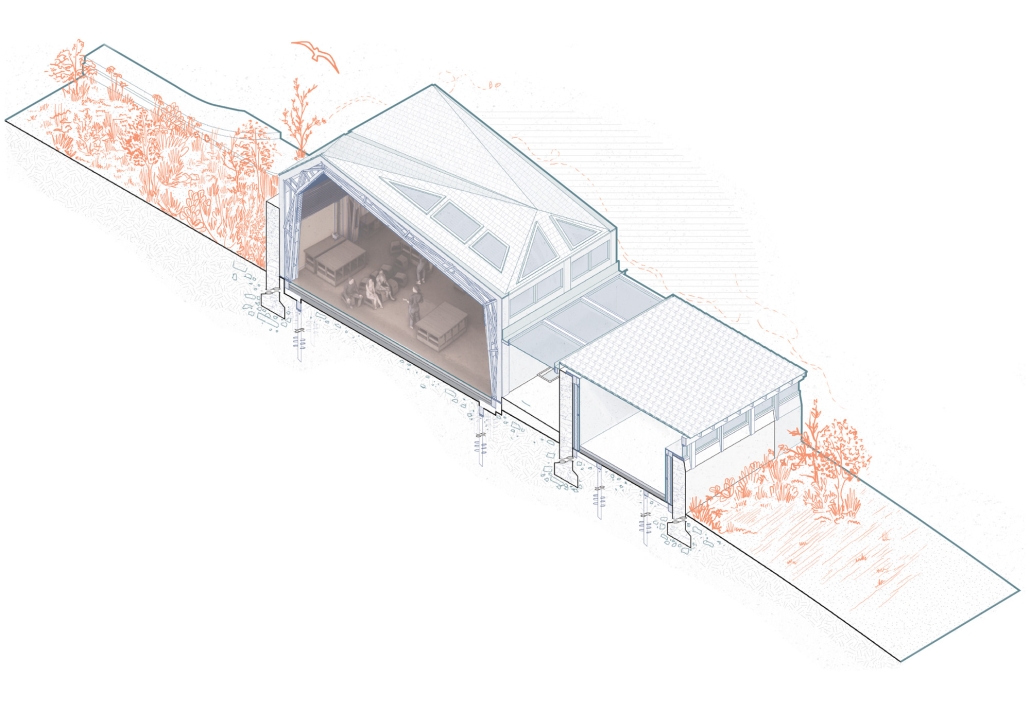

Set at the foot of the Lomond Hills in the historic settlement of Kilgour, Scotland, the Watershed Collective transforms an abandoned farmstead into a multidisciplinary centre for water stewardship. Situated at the headwaters of the River Eden, the site lies within a richly layered ecological and cultural landscape—marked by woodlands, flowing burns, and sweeping views—ideal for reflection, education, and environmental engagement.

The project reimagines Kilgour as a shared platform for learning, collaboration, and care. It offers a constellation of flexible spaces, including collaborative studios for practitioners and researchers, educational environments for schools and communities, and outdoor infrastructure such as interpretive trails and water-monitoring points that promote hands-on interaction with the watershed. A central feature of the programme is a suite of integrated spa and wellness facilities, designed to cultivate a deeper sensory and restorative connection with water and the surrounding landscape.

Architecturally, the design embraces regenerative principles—employing sustainable materials, vernacular forms, and water-sensitive strategies to create a reciprocal relationship with the watershed. Rather than simply benefiting from the site’s ecological richness, the architecture contributes back to it, embodying a model of mutual care between human and landscape systems.

Inclusive and multi-generational, the Watershed Collective serves local landowners, educators, conservationists, policymakers, and eco-tourists alike. Grounded in Falkland Estate’s ethos of stewardship, the centre invites users not only to observe the watershed but to dwell within it, as active participants in its cycles, responsibilities, and potential futures. It stands as both a functional hub and a conceptual anchor for ecological awareness and collective resilience.

This project won the Purcell Prize: Best M.ArchD Year 2 for its contextual response to the brief.

Instagram: @j.s_design_, @oxfordbrookes

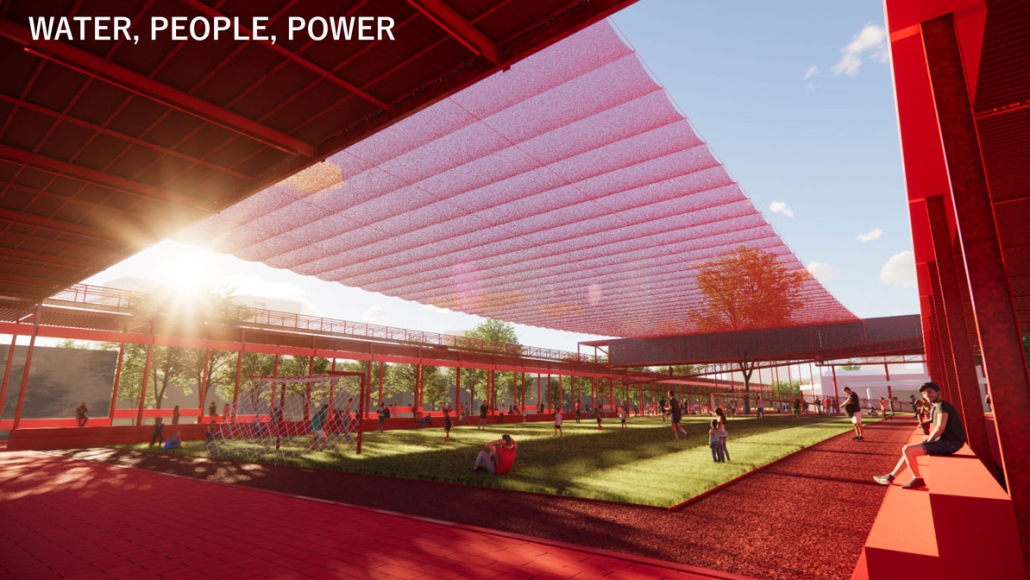

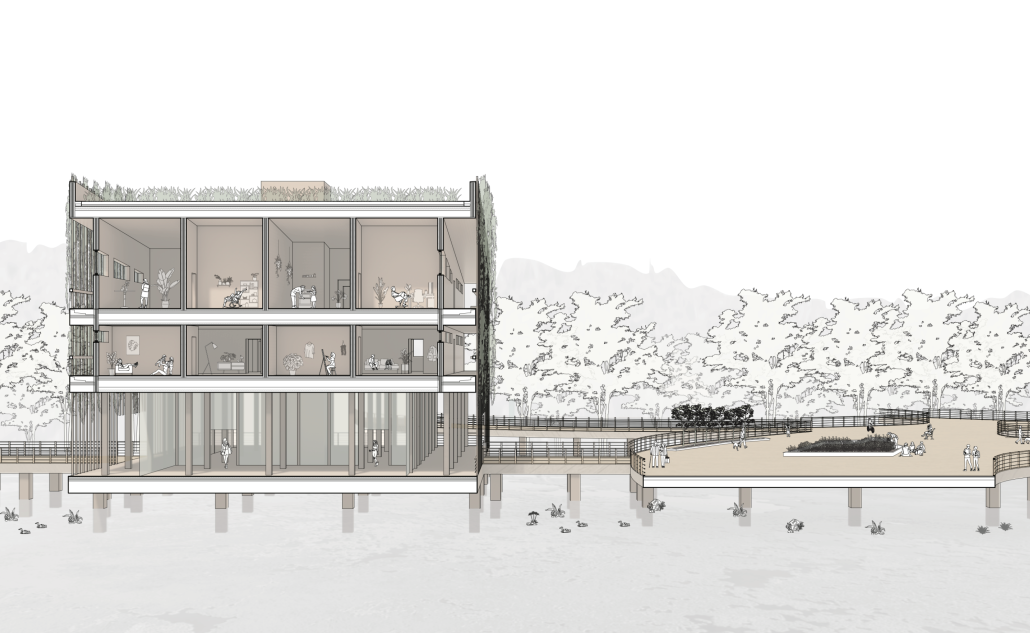

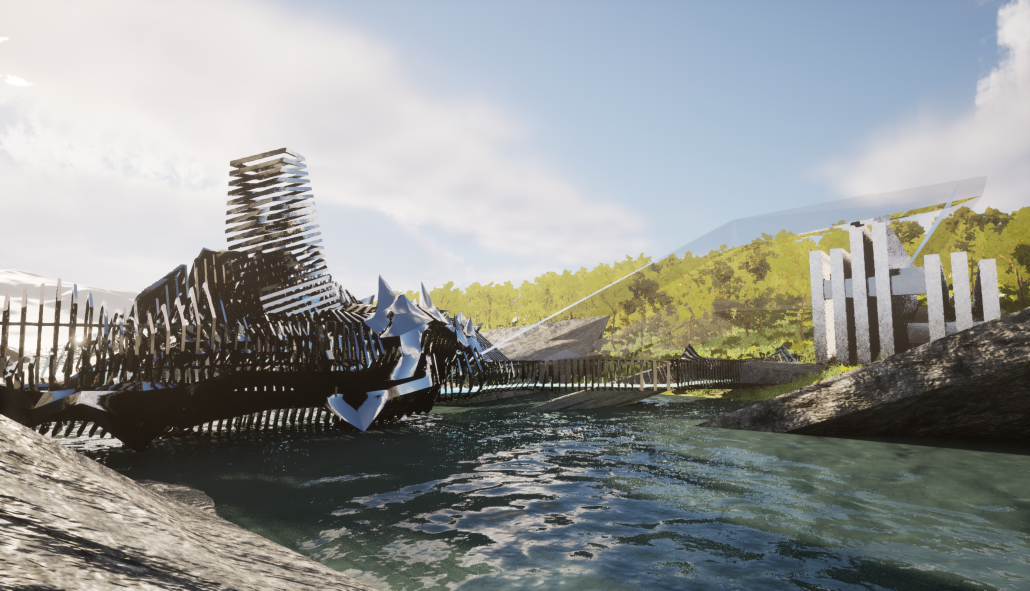

Water, People, Power: Architecture as Infrastructural Socio-Ecology by Daniel Choi, B.Arch ’25

Academy of Art University | Advisor: Diego Romero Evans

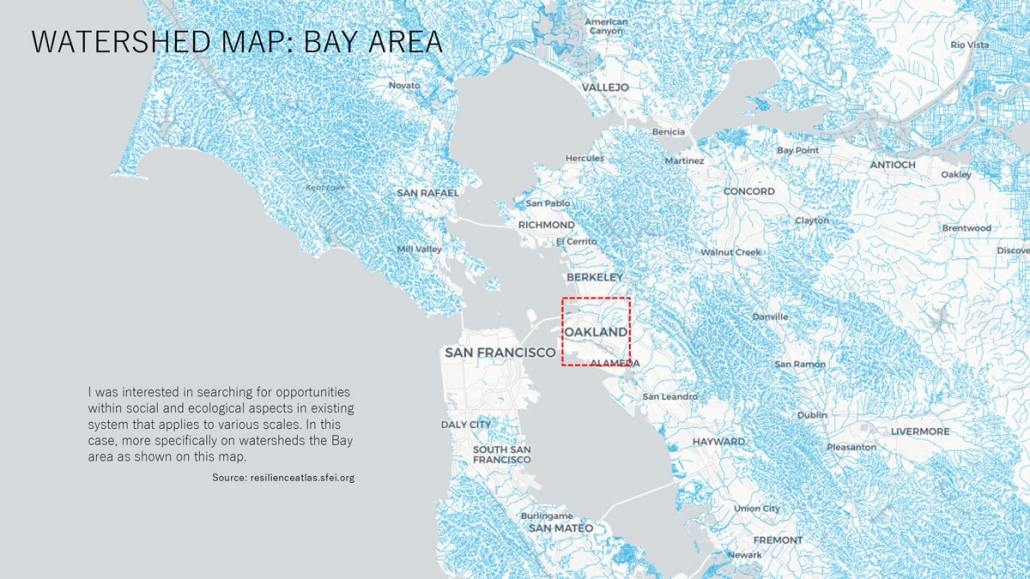

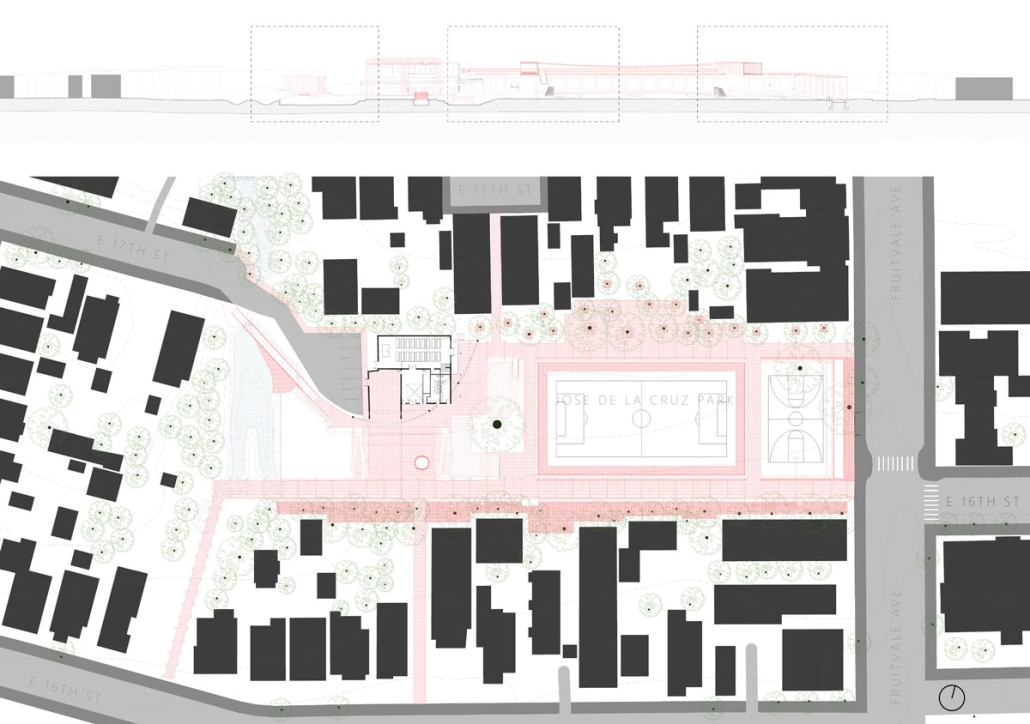

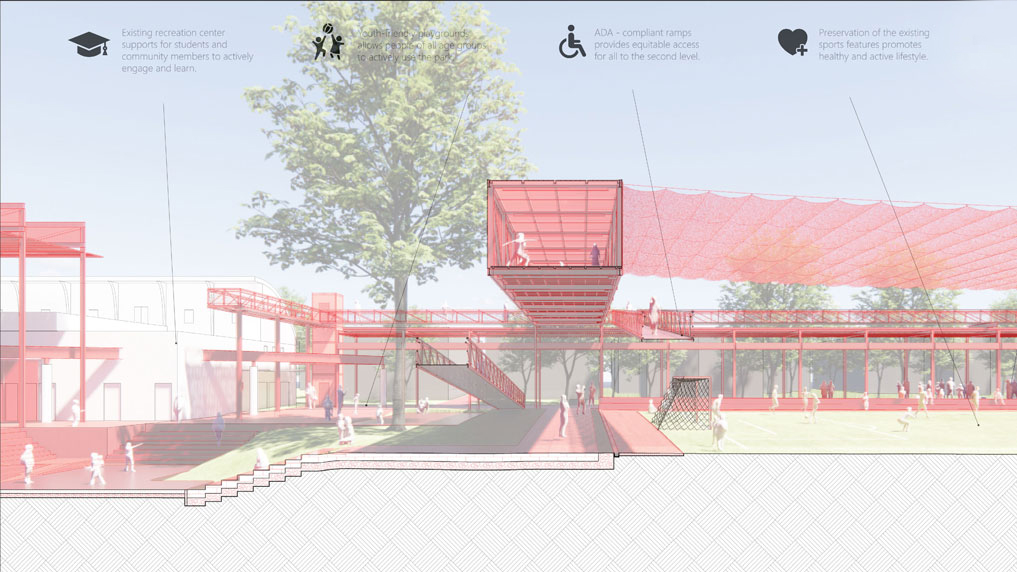

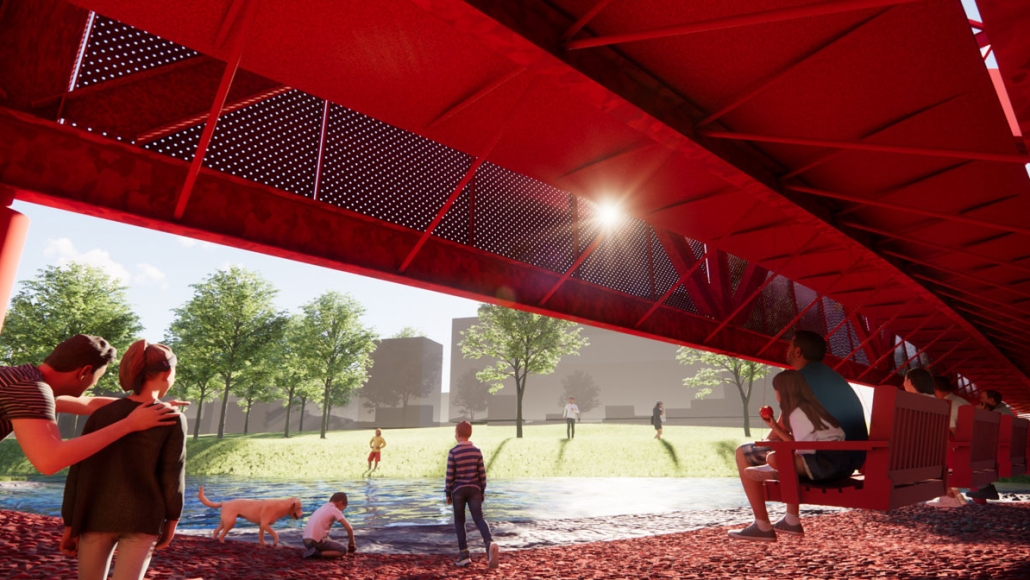

This thesis project envisions architecture as an open system, one that operates within the logics of: watershed ecologies, cultural memory, and collective resilience. Through the daylighting of buried creeks and the integration of flood mitigation, habitat regeneration, and rainwater reuse, the proposal transforms urban infrastructure into a socio-ecological commons.

Anchored by the Carmen Flores Recreation Center, the design blurs disciplinary boundaries between building and landscape, infrastructure and ritual. By reclaiming flows of water, people, and meaning, it offers a speculative yet actionable framework for a resilient, place-based urbanism rooted in adaptation, dialectical reciprocity, and care.

The Sausal Creek watershed begins in the Oakland Hills and emerges into the Oakland Estuary of the San Francisco Bay Area. In the Fruitvale neighborhood of Oakland, the Sausal Creek is buried in an underground culvert near the Carmen Flores Recreation Center in the Jose de la Cruz Park. The objective of this project is to daylight the creek and enhance its connection with the community.

The Sausal Creek hosts a rich and diverse ecosystem that various plants, animals, and fungi inhabit. Many people use the creek, and a non-profit organization called Friends of Sausal Creek continues to steward the health and safety of the creek.

This project won the B.Arch Thesis Award.

Instagram: @diegoromeroevans

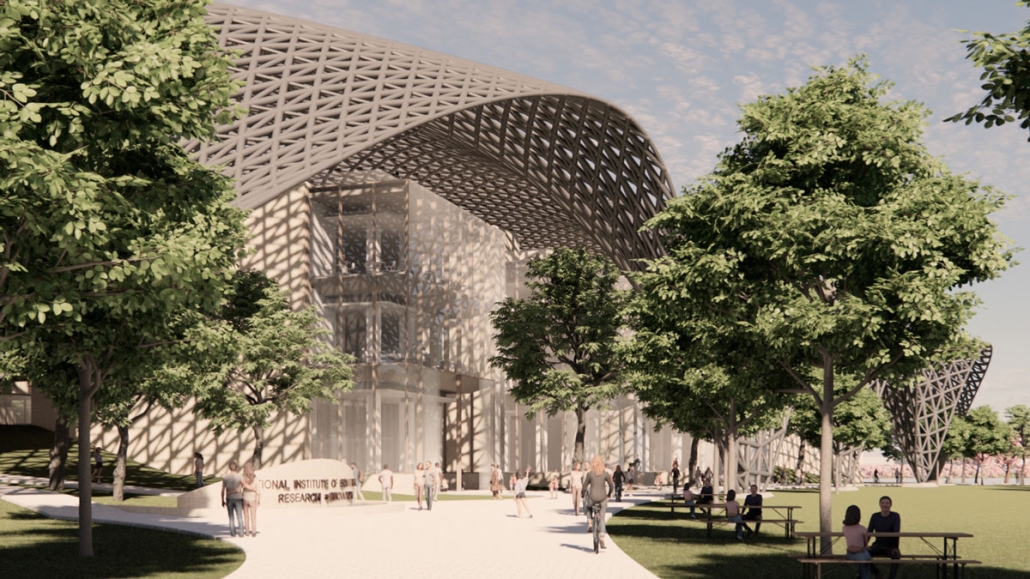

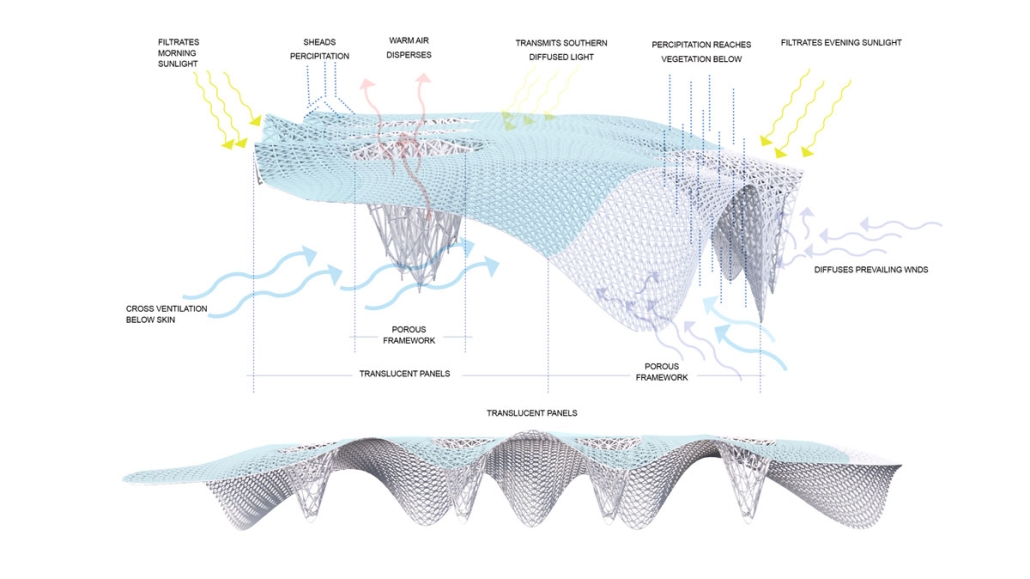

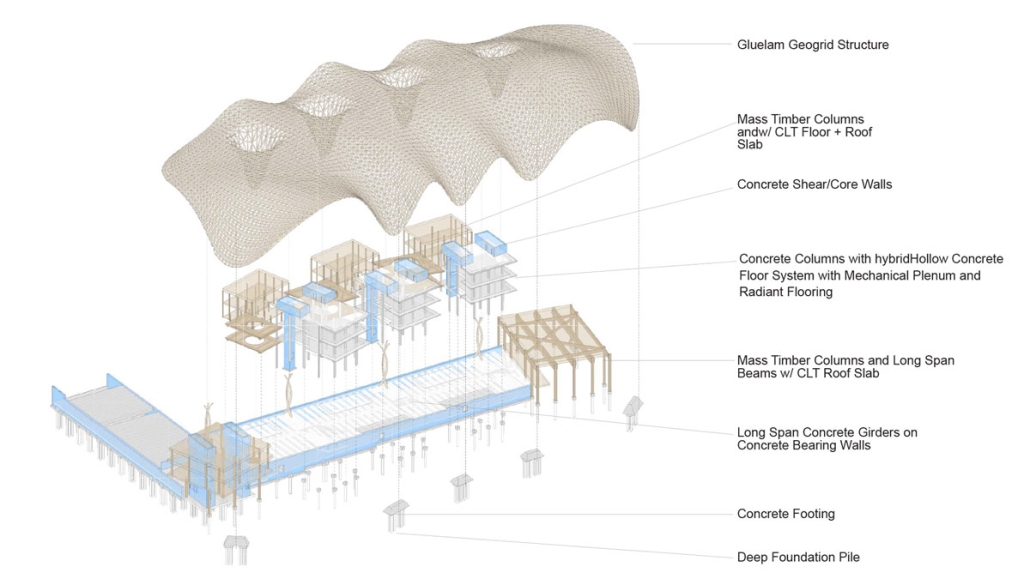

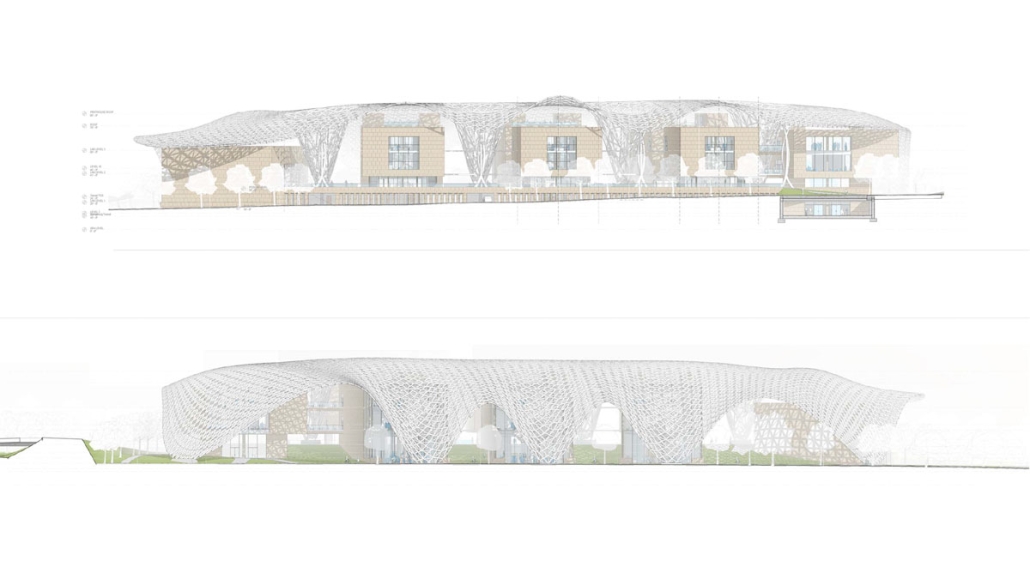

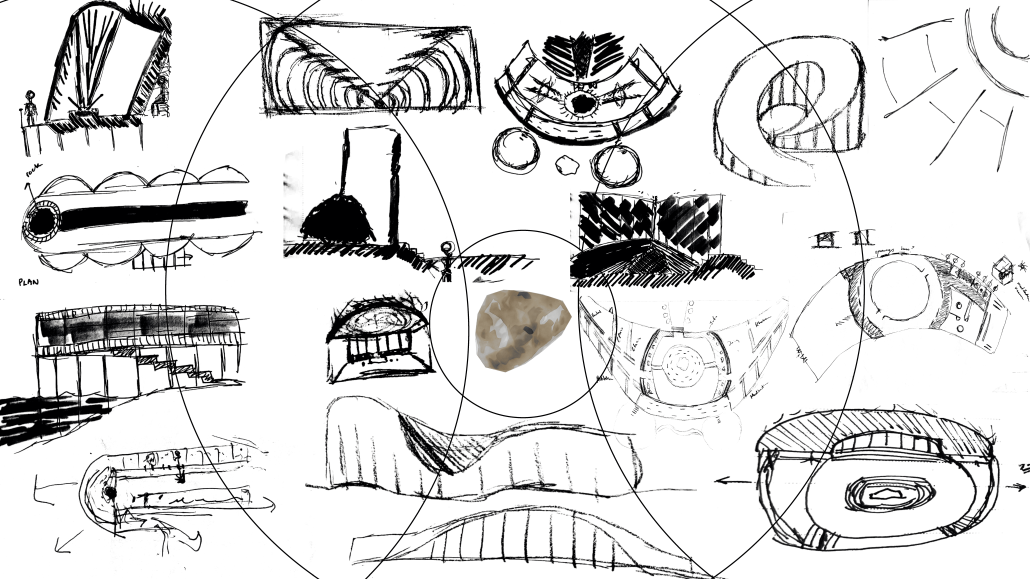

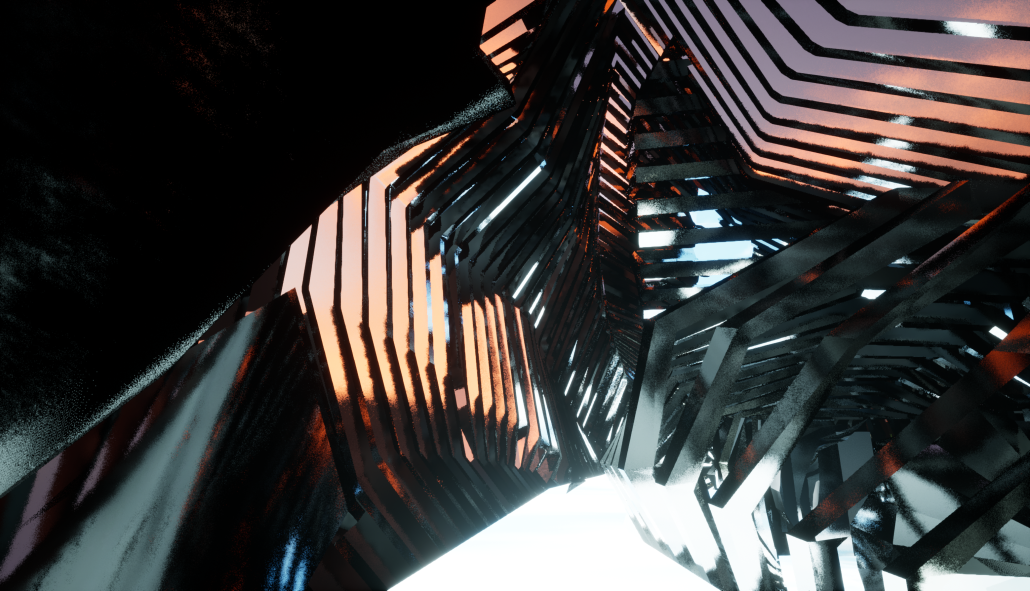

A Gradient of Environments: National Institute of Biomaterial Research and Innovation by Zachary Smith, B.Arch ’25

Academy of Art University | Advisor: Jason Austin

This project explores the concept of gradations of environments inspired by natural systems. It dissolves the boundary between the built and natural environment, reimagining the relationship between architecture and ecology. Rooted in the historical context of the National Mall, where clear delineations between landscape, monument, and building have long been upheld, this project challenges convention by proposing a hybrid structure. Dedicated primarily to advancing research in bio-based materials for the built environment, it responds to the urgency of the climate crisis, symbolizing a transformative vision for sustainable architecture and integrated design.

Instagram: @aus.mer

PENN CENTER PLATFORM by Kaylan Pham, Niknaz Tikkavaldyyeva & Kailey Wiliams, BS in Architecture ’25

Georgia Tech | Advisor: Danielle Willkens

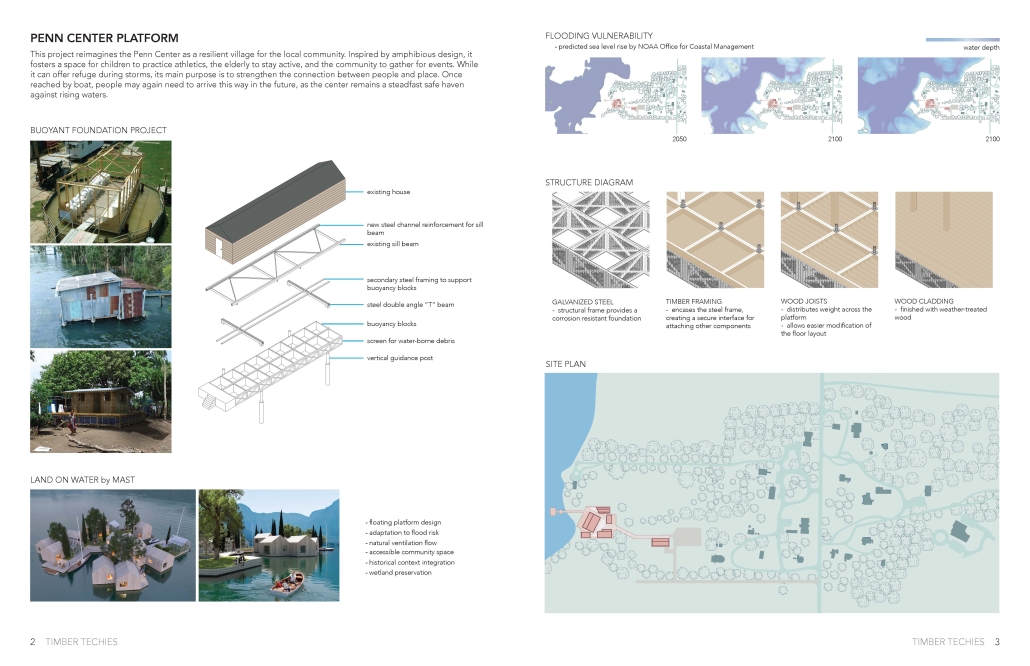

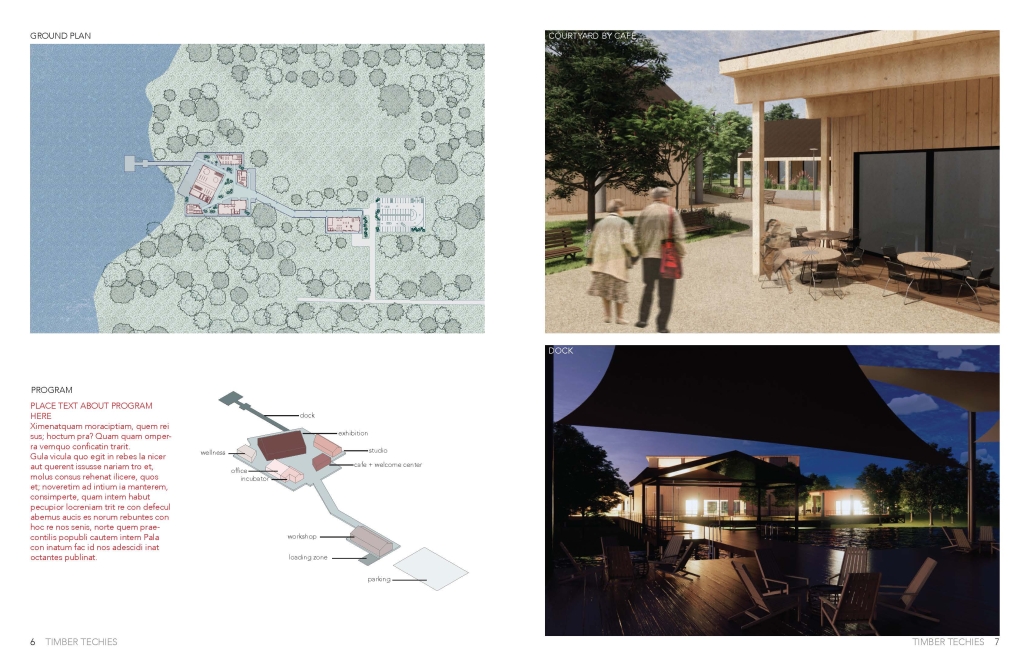

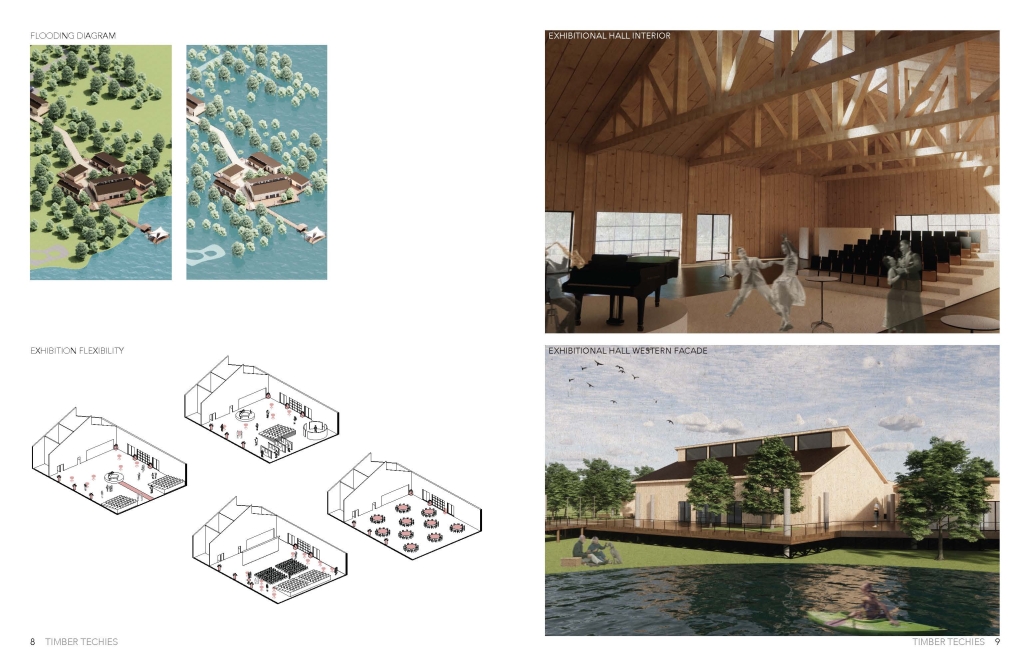

This project reimagines the Penn Center as a resilient village for the local community. Inspired by amphibious design, it fosters a space for children to practice athletics, the elderly to stay active, and the community to gather for events. While it can offer refuge during storms, its main purpose is to strengthen the connection between people and place. Once reached by boat, people may again need to arrive this way in the future, as the center remains a steadfast safe haven against rising waters.

Instagram: @georgiatech.arch, @archDSW

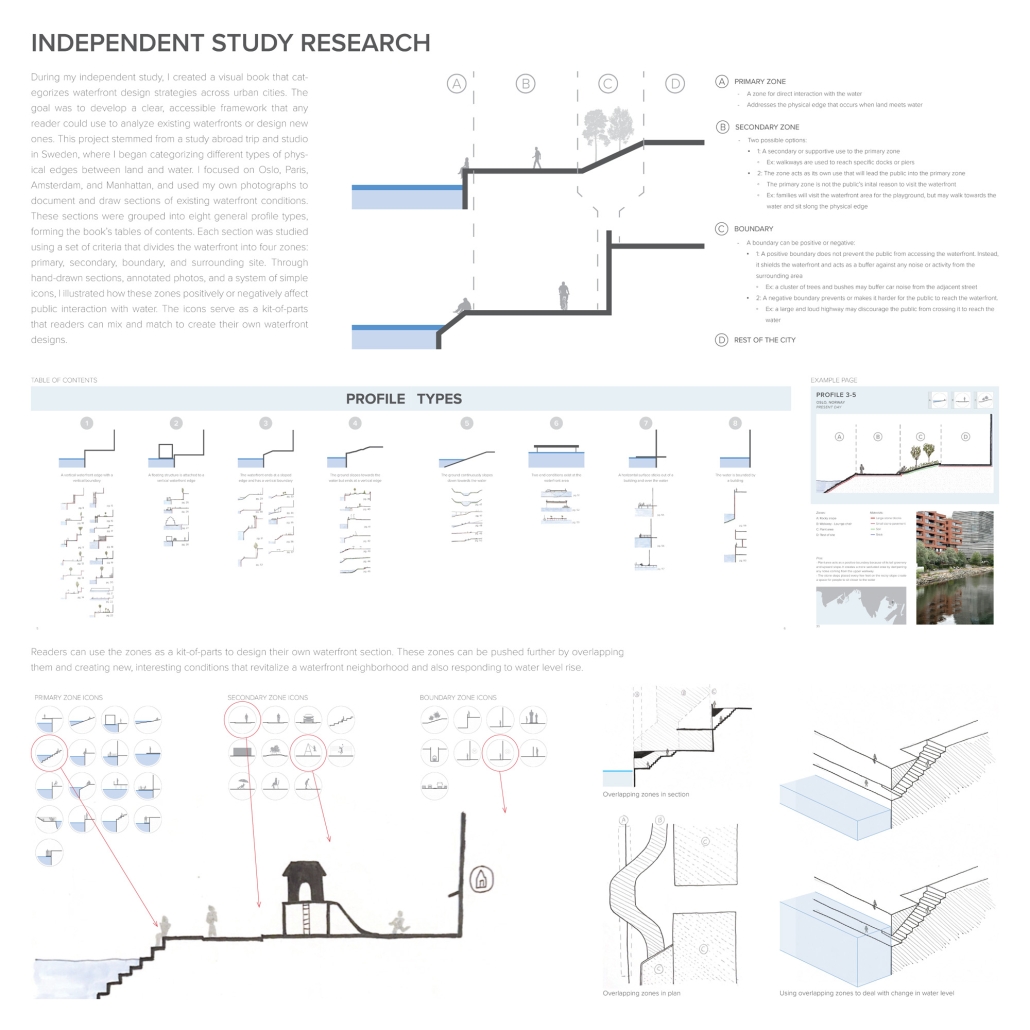

Developing New Methods of Designing the Water’s Edge by Elizabeth Stoganenko, B.Arch ’25

New Jersey Institute of Technology | Advisor: Thomas Ogorzalek

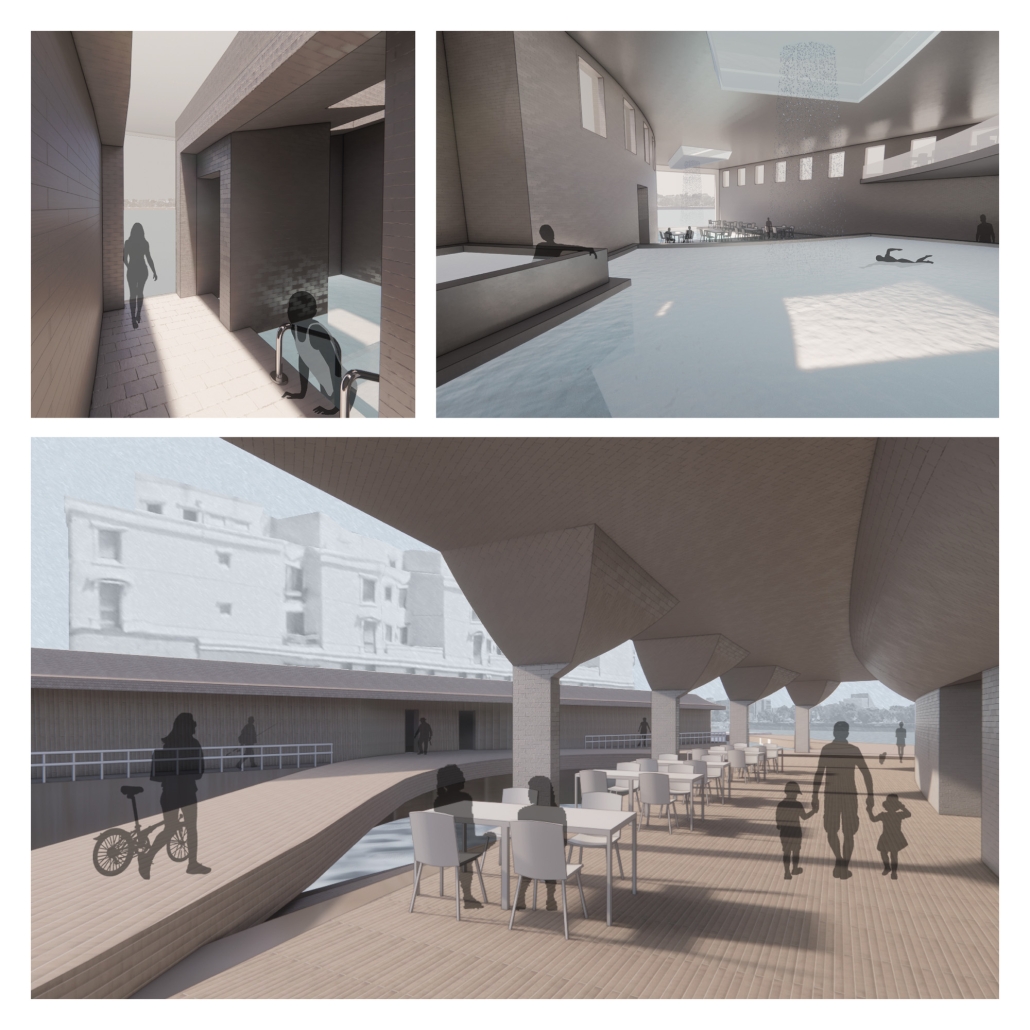

This thesis focuses on re-examining our relationship to waterfront conditions. In doing so, the work seeks to provide new methods of analyzing and designing at the water’s edge that will restore and revitalize our relationships with underutilized waterfronts while responding to climate change challenges.

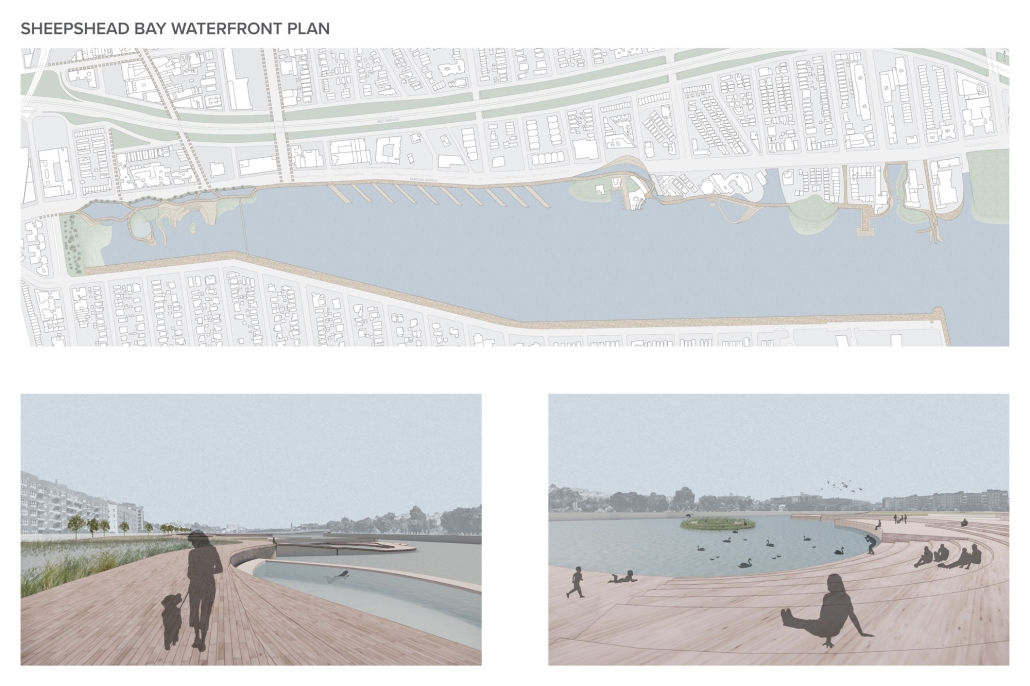

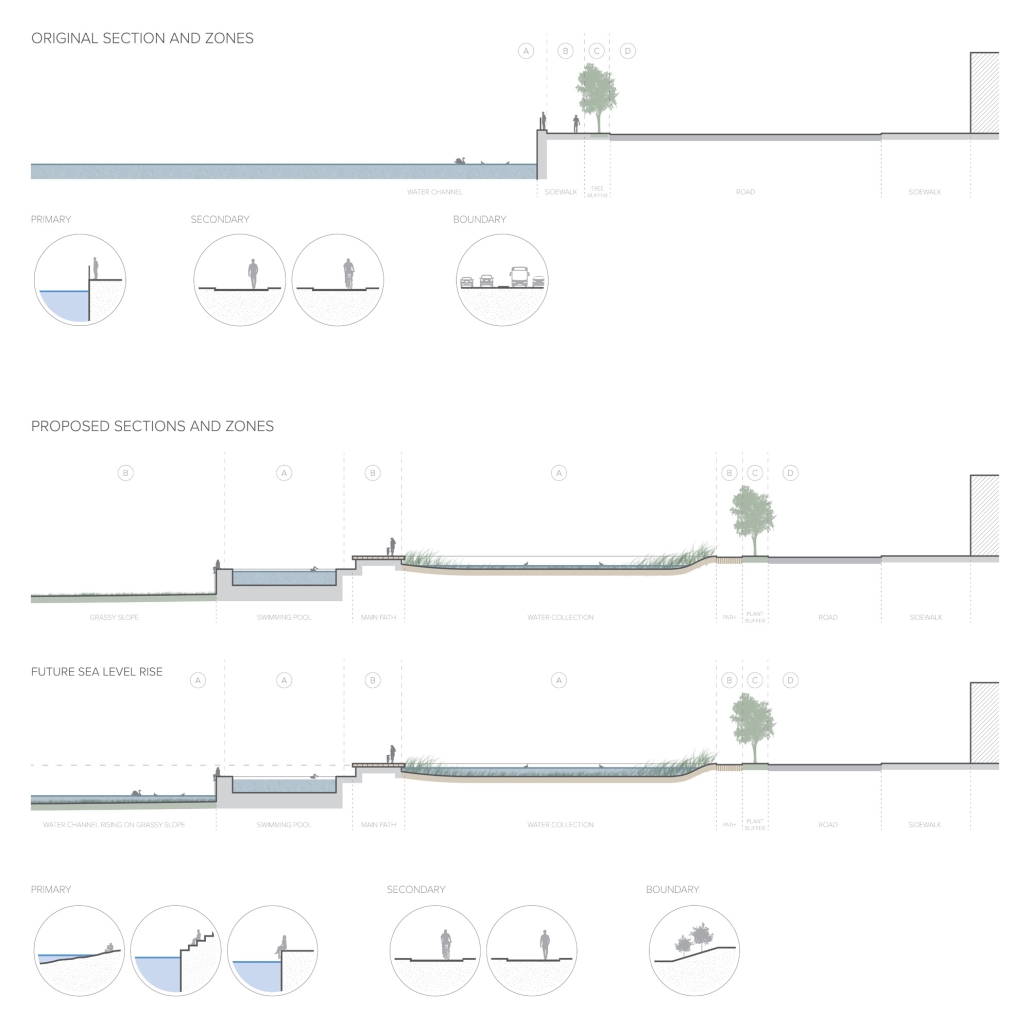

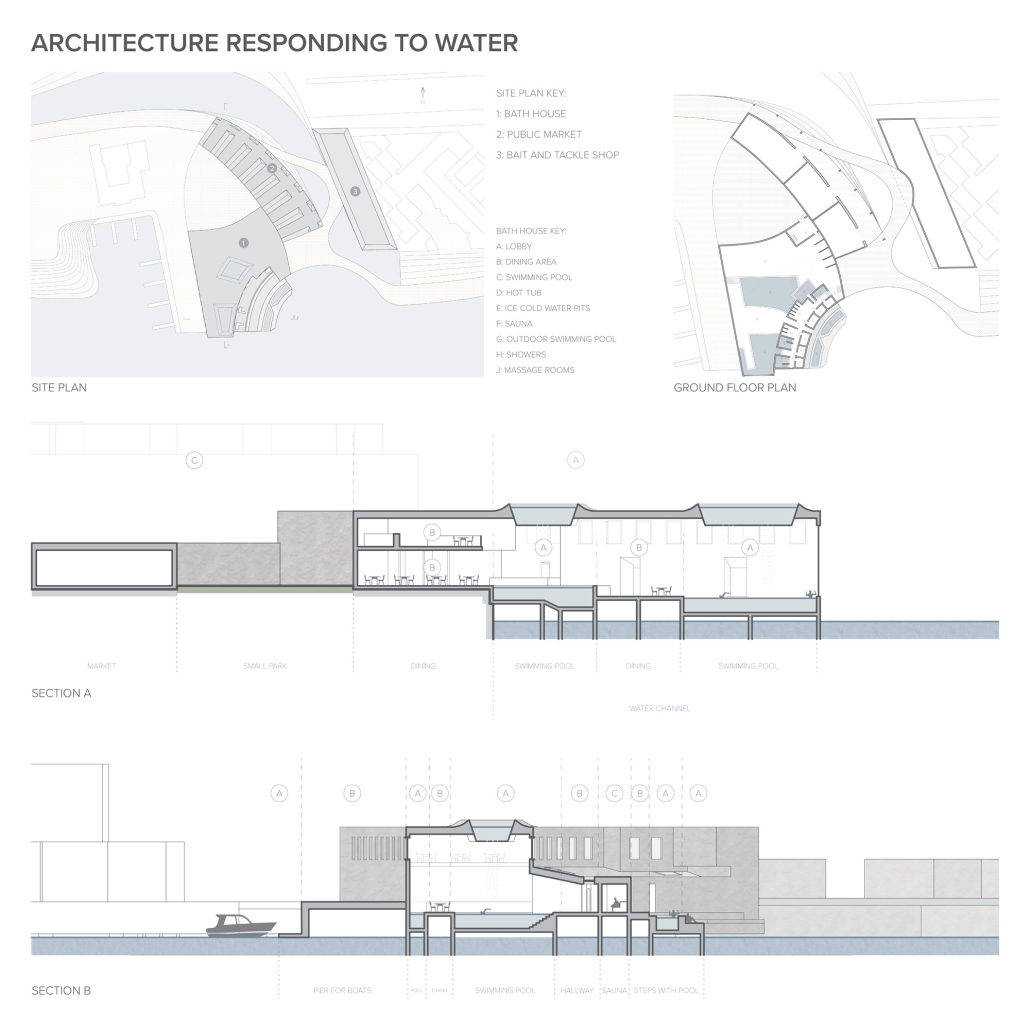

The project focuses on the Sheepshead Bay waterfront neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. Once a thriving fishing village and tourist destination, it now struggles to provide activities that bring the public to the neighborhood and [the] water’s edge. It was hugely impacted by Hurricane Sandy in 2012 due to its lack of flood resilience design. Sheepshead Bay is representative of the challenges facing many other coastal communities and provides an opportunity to serve as a prototype of how we may go about rethinking the water’s edge. By utilizing research from my Independent Study, new waterfront conditions have emerged through the act of design that have created new relationships with the water for all stakeholders, humans, and the environment. This design rethinks the waterfront plan along Emmons Avenue and focuses on a particular area to see if architecture can interact with the water in new ways as well. The building is placed on both sides of a proposed canal, providing space for a market to appeal to the public, a bait and tackle shop for the local fishermen, and a bathhouse. Both markets point towards the canal and create areas for visitors to walk and sit along the water. The bathhouse stretches past the original waterfront edge and is built over the Sheepshead Bay channel. The water from the channel is pumped up and filtered to use in the bathhouse, creating an additional way for people to utilize the natural water source.

This project won the Thesis Prize.

Instagram: @stoganenko.architecture, @njit_hillier

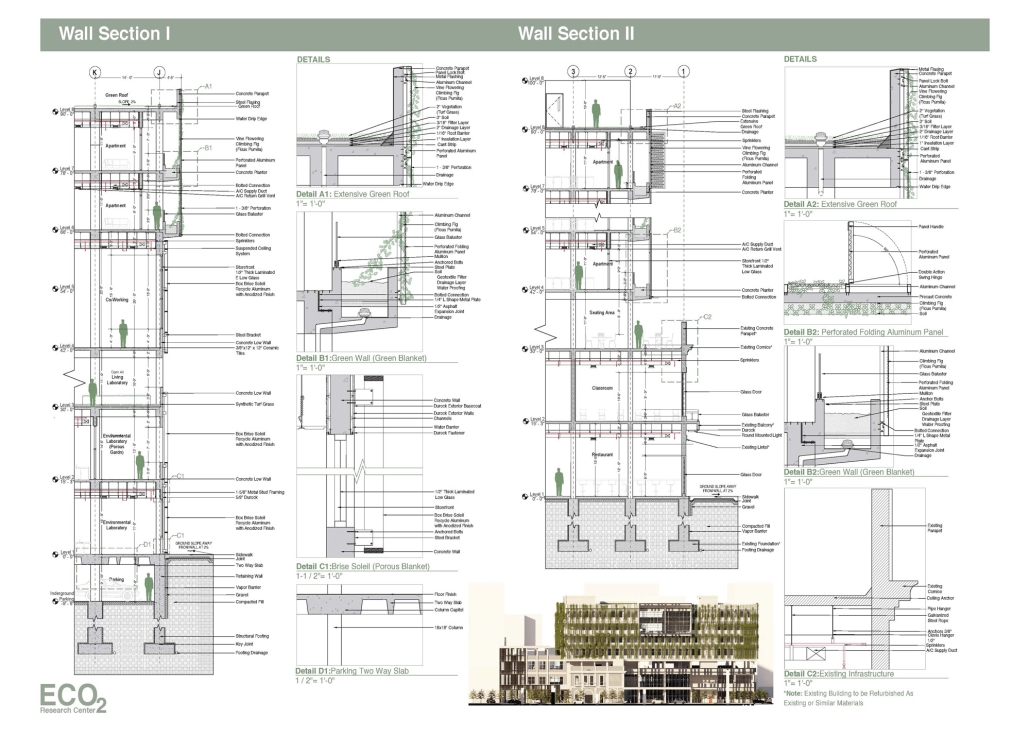

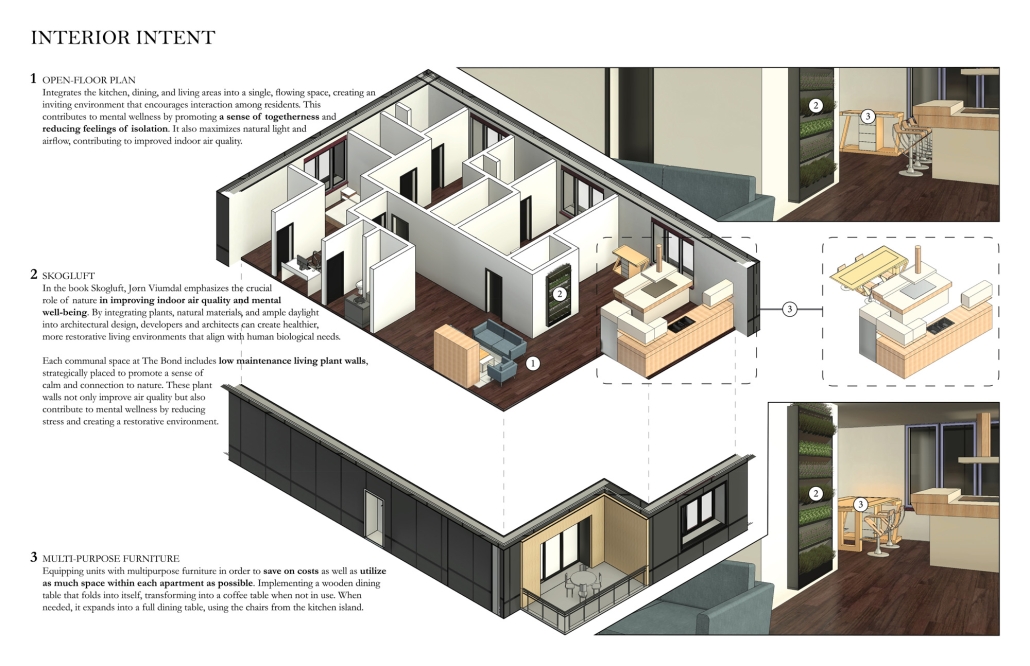

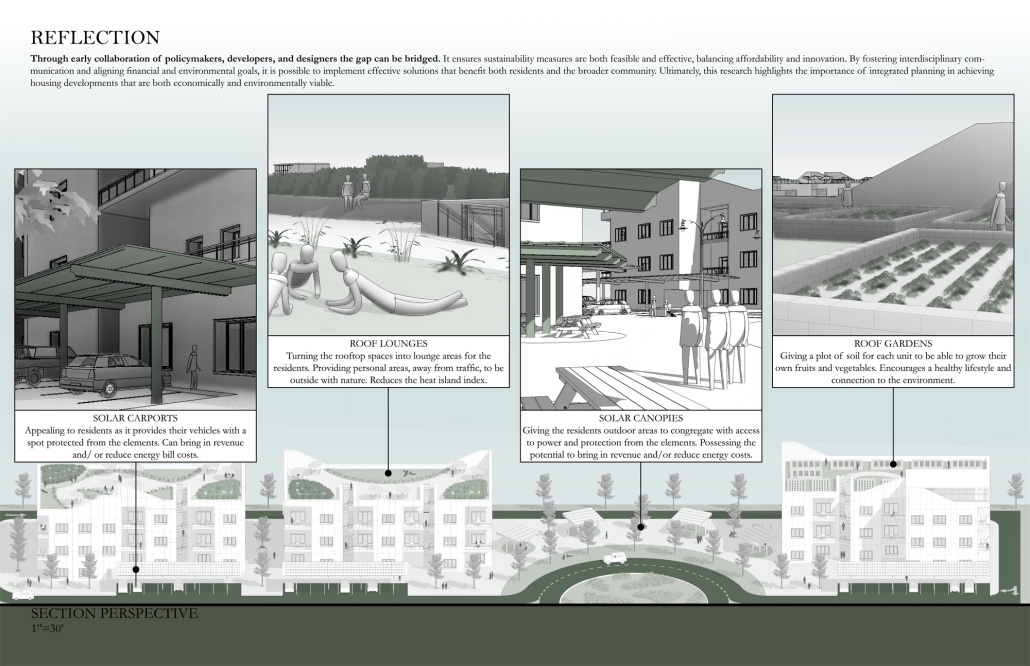

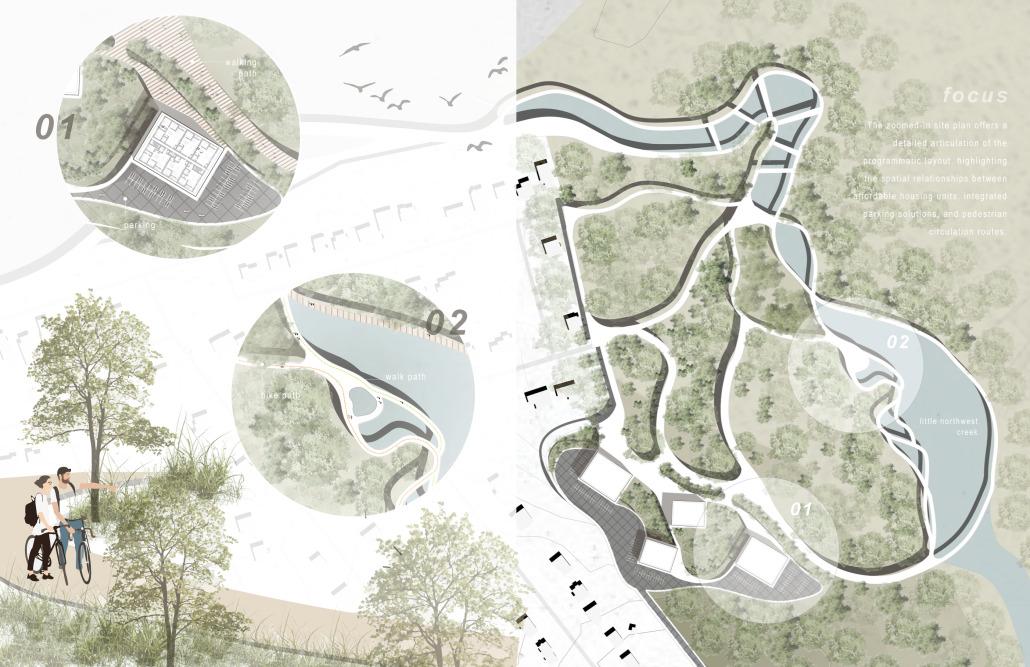

Breaking Barriers: BRIDGING THE DIVIDE BETWEEN SUSTAINABILITY, AFFORDABILITY, AND INNOVATION IN HOUSING by Kamryn J. Brown, M.Arch ’25

Florida A&M University | Advisor: George Epolito, Mahsan Mohsenin & Ronald B. Lumpkin

“Breaking Barriers: Bridging the Divide Between Sustainability, Affordability, and Innovation in Housing” explores a critical issue in contemporary architectural practice—the challenge of designing sustainable housing that is both affordable and innovative. Set in the context of Tallahassee, Florida, this thesis identifies a persistent disconnect among policymakers, developers, and designers, which often results in housing that sacrifices long-term environmental and social benefits for short-term cost savings.

This research proposes that sustainable and affordable housing are not mutually exclusive goals, but rather objectives that, when guided by collaboration and innovative thinking, can reinforce one another. While existing governmental policies support green building practices, a significant roadblock remains: the perception that sustainable materials and technologies are inherently too costly for affordable housing projects.

To address this, the study employs a research-based design methodology that integrates case study analysis, sustainable design principles, and financial feasibility assessments. The resulting proposal is not just a theoretical exploration but a practical design solution—an affordable housing prototype that emphasizes energy efficiency, community well-being, and architectural distinction. It demonstrates that strategic planning and creative design can produce developments that are environmentally responsible, economically viable, and culturally relevant.

This thesis contributes to a growing body of knowledge advocating for interdisciplinary cooperation in addressing housing crises. By presenting a replicable framework rooted in innovation and equity, it offers a blueprint for municipalities like Tallahassee—and beyond—to rethink how we build the homes of tomorrow.

Instagram: @famusaet, @famu_masterofarch

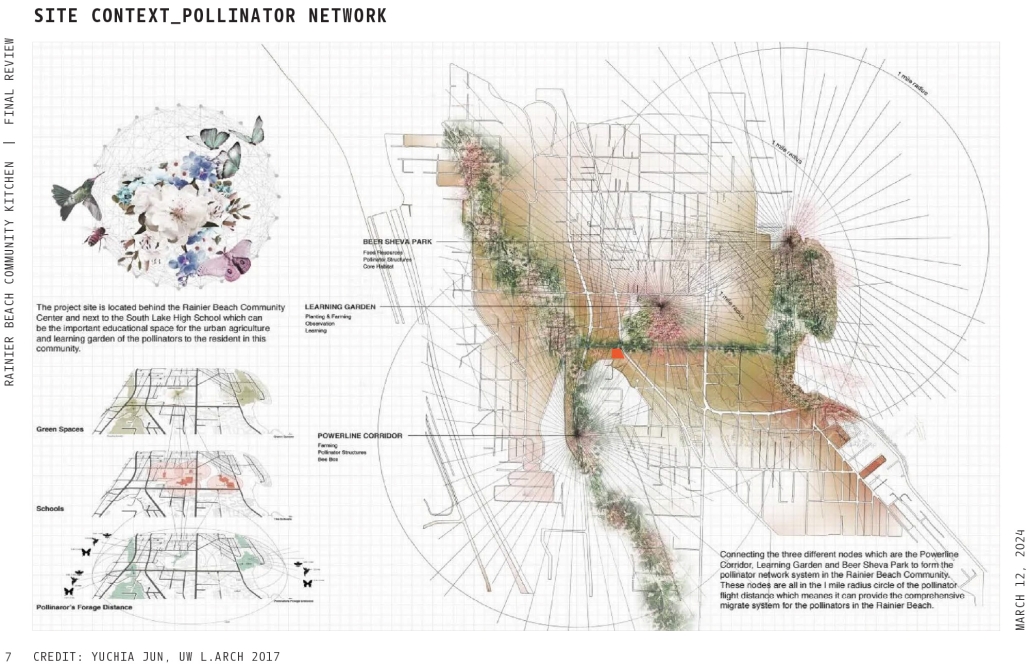

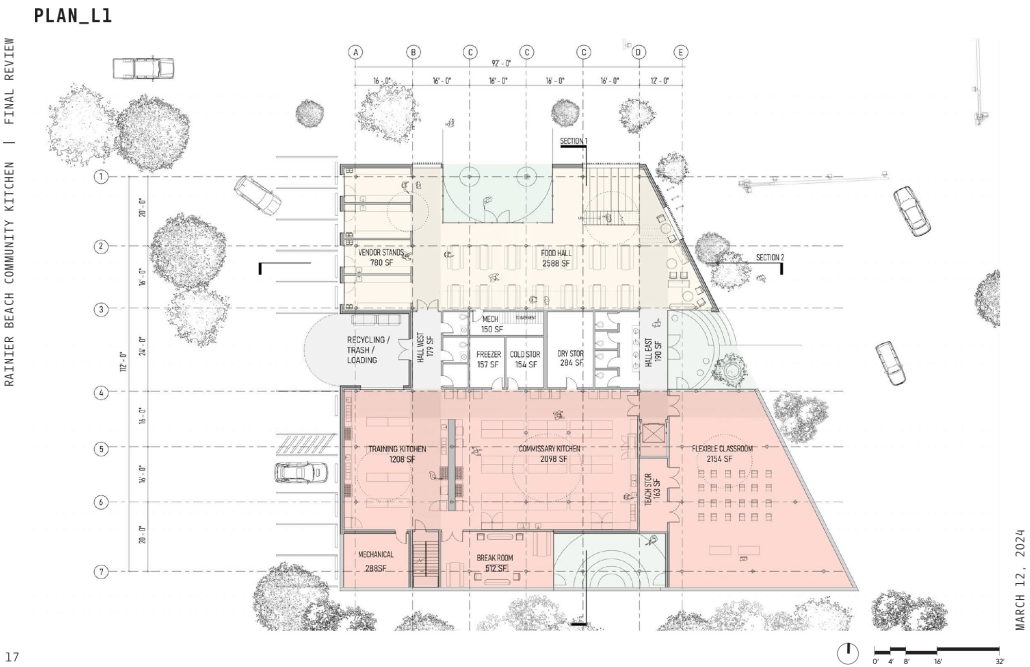

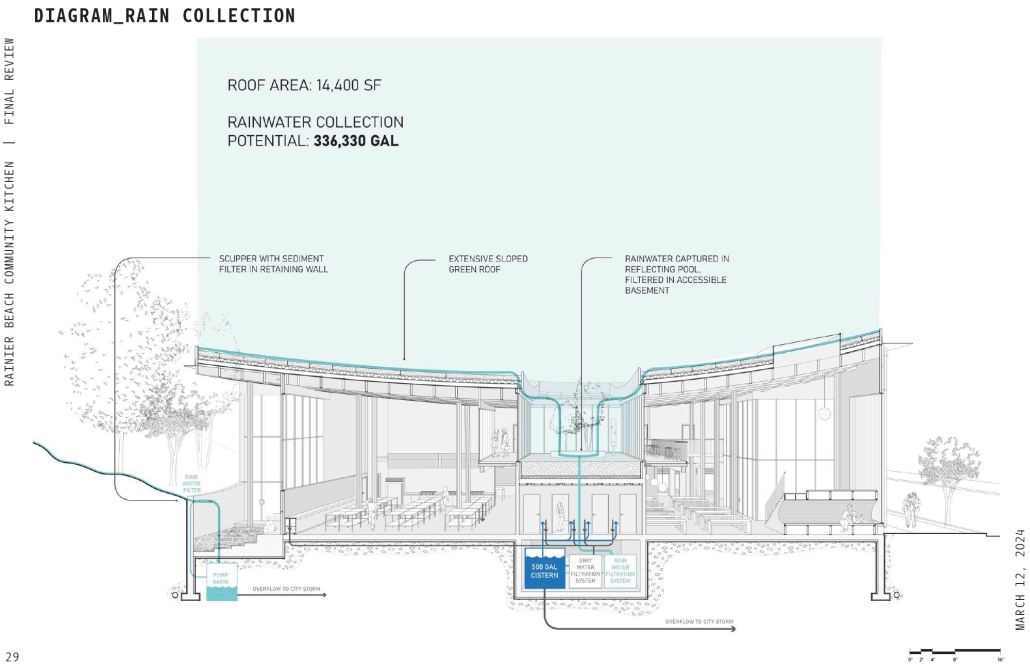

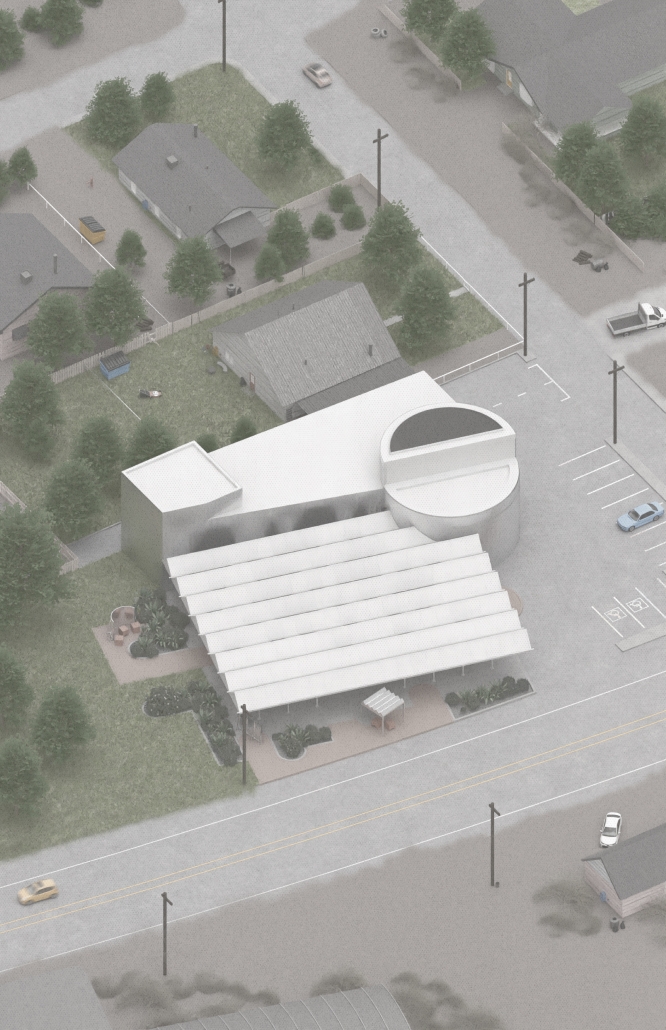

Rainier Beach Community Kitchen by Eleanor Lewis, M.Arch ’25

University of Washington | Advisor: Patreese Martin

The required Architecture 504 design studio is focused on building systems integration with a particular focus on sustainability and community. The assigned program for 2024 was a commissary kitchen in Seattle’s Rainier Beach neighborhood, in close proximity to the regional light rail station. This proposal strives to provide workers and visitors a moment of respite from the urban environment. It employs a host of high-performance building strategies and a limited palette of natural materials to educate and soothe its inhabitants. In so doing, it employs the following strategies:

WATER

- Return the site to before-development levels of rainwater catchment

- Filter water through a rooftop garden

- Capture excess rainwater in underground cisterns

- Filter graywater and reuse for toilet flushing

- Express water catchment where possible

ENERGY

- Daylighting through translucent skylights and use of reflective materials

- All-electric building

- VRF heat sharing system

- Thick cork insulation to reduce conditioning loads

- Provide backing for future PV arrays

- Relatively low window-to-wall ratios

RESOURCES

- Use sustainable and durable cork siding, which also acts as continuous insulation

- Minimal concrete in the foundation only

- Light wood frame construction to minimize steel use

- Natural, non-toxic materials

- Use two-in-one materials where possible (cork, plywood)

- Use stainless steel in moderation for durable, easy-to-clean surfaces

ECOSYSTEMS

- Design a building that gives back more than it takes away

- Provide habitat for animals, including pollinator garden, bird housing, and bee hives

- Fritted windows to protect birds

- Filter site water and reuse or return to the natural ecosystem

- Consider material sourcing to foster the best manufacturing practices

This project received commends for the studio.

Instagram: @l.n.r, @nitramxyz

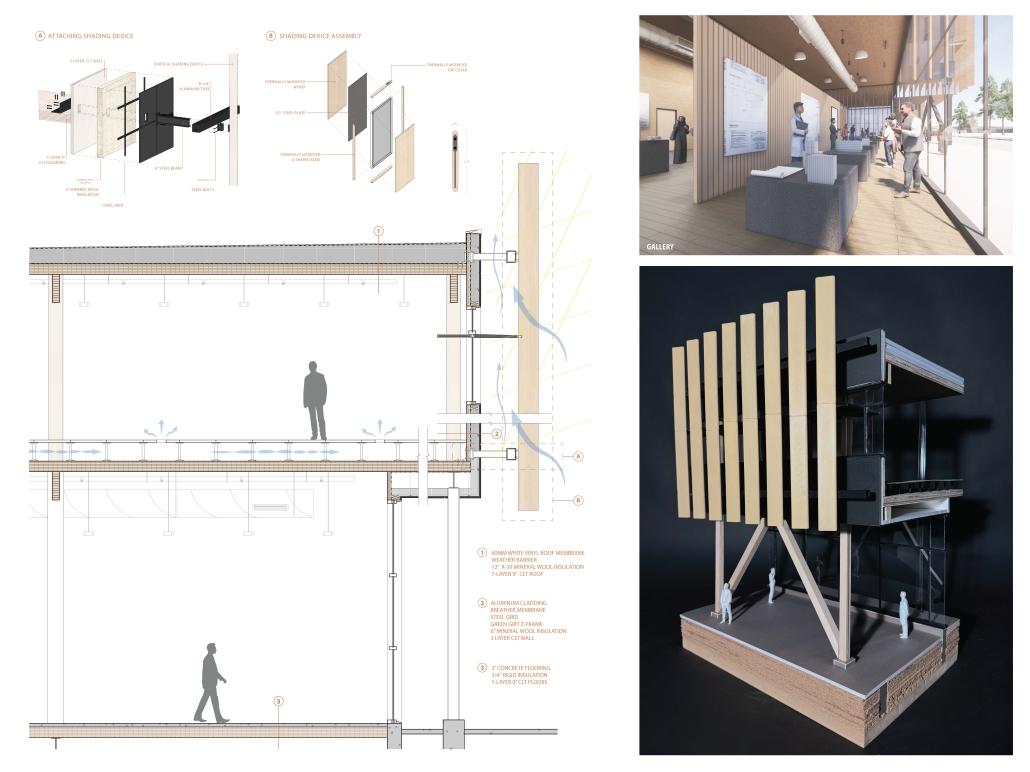

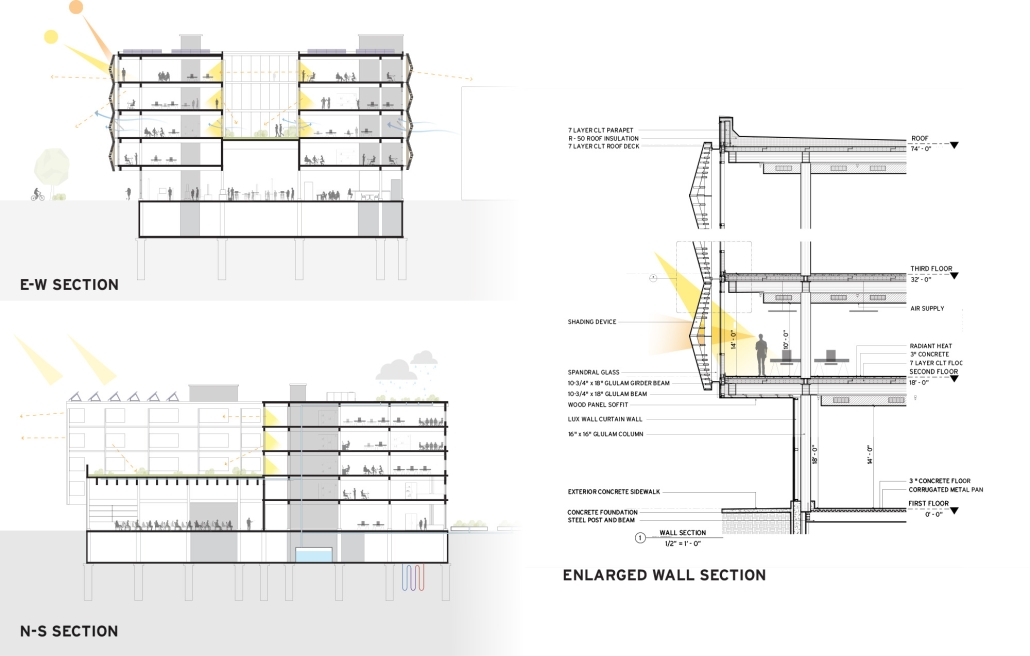

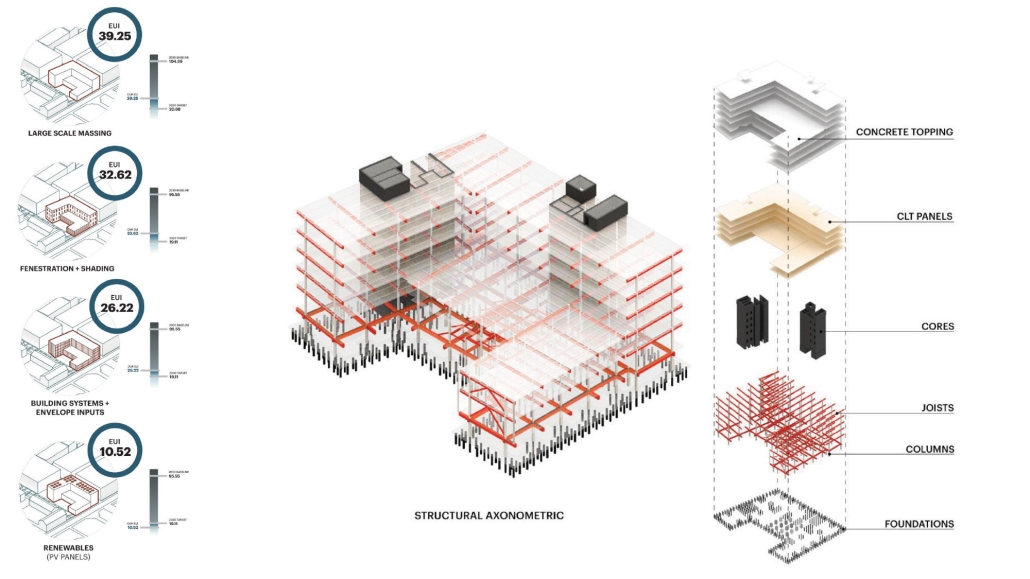

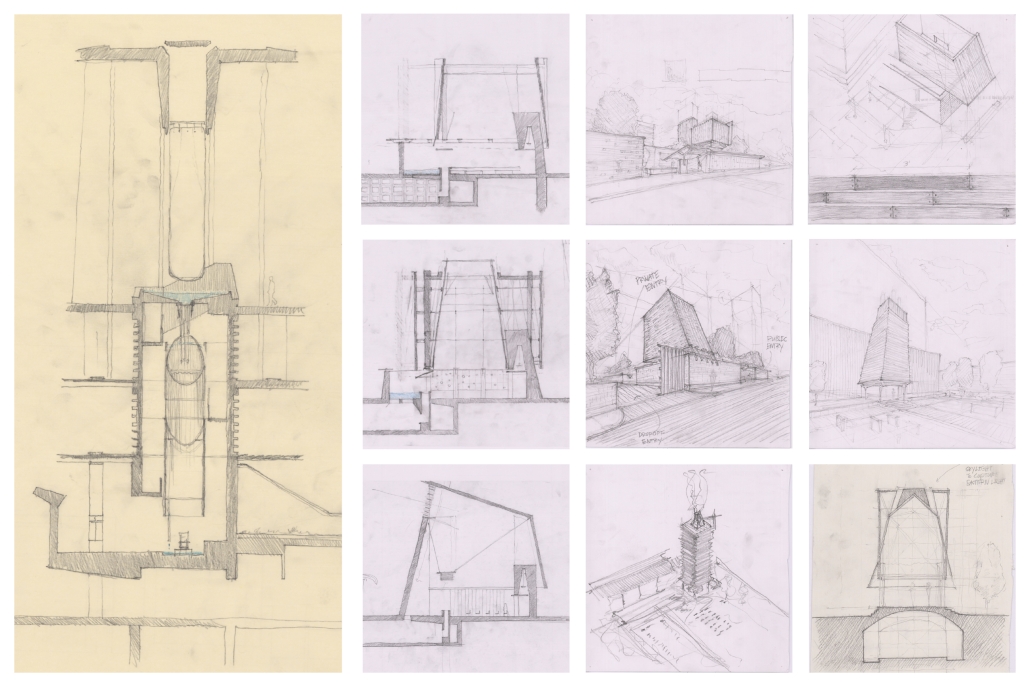

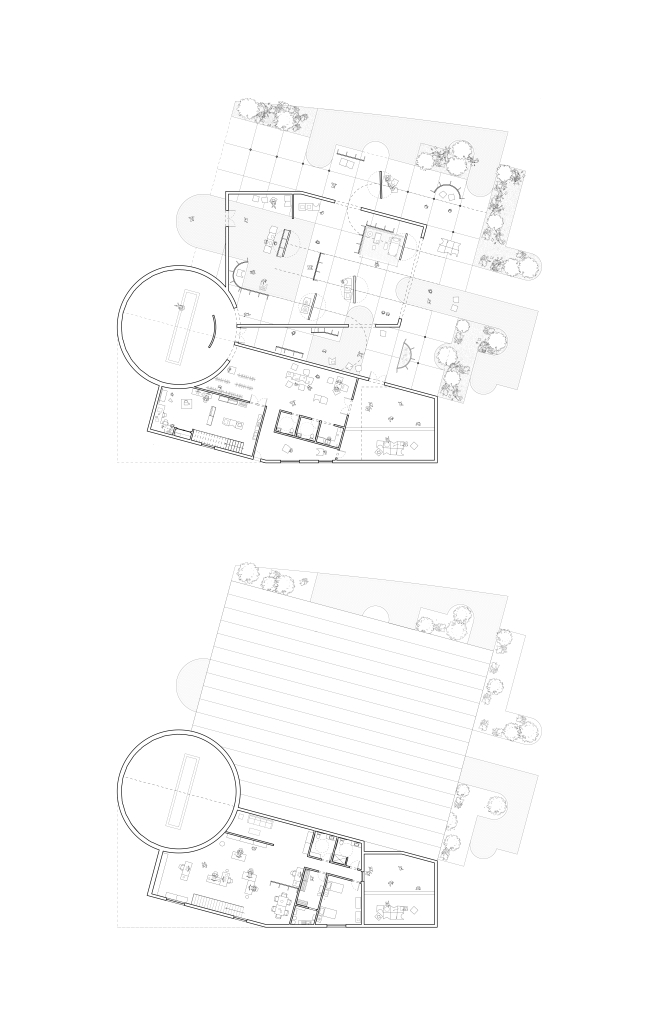

V-Lab Innovation Center by Allie Kotsopoulos, Emily Neufeld & Charles Stockton, B.Arch ’25

University of Detroit Mercy | Advisors: James Leach & Kristin Nelson

The project is focused on three goals: to optimize occupant experience, to minimize energy waste and to connect to the Dequindre Cut Greenway. Our early research on the Detroit East Riverfront and analysis of the existing site conditions, pedestrian pathways, and environmental conditions led us to the idea of improving the connection between people and urban and natural spaces. We also took a structured approach to sustainability, considering how materiality and technology could improve the environment of and positively impact the occupants of a building. Specifically, we worked on energy-use, shading/daylighting strategies, and understanding our design’s carbon footprint.

Our design is informed by Detroit’s current climate with its changing seasons and anticipates increasing volatility due to climate change. We conducted multiple rounds of experimental research using the Cove tool to model and refine our active and passive systems. To ensure our goal of a sustainable building, we optimized daylighting and shading, energy use of building systems, and rainwater management. We spent extensive time researching shading devices and geometries to admit a large amount of natural daylight with minimal glare while providing shading when necessary. Along with sustainability came designing for occupant needs. We conducted research on office buildings and design strategies to create a welcoming, comfortable space that encouraged people to connect with one another and their surroundings. Our approach was driven by collaboration and flexibility in the work environment. Our programming prioritizes team collaboration and occupant comfort. The final design concept creates a connection point, linking the Dequindre Cut and East Riverfront as well as passing pedestrians and building occupants.

Instagram: @alliekotsopoulos, @emilyyneufeld, @stocktondevelopment

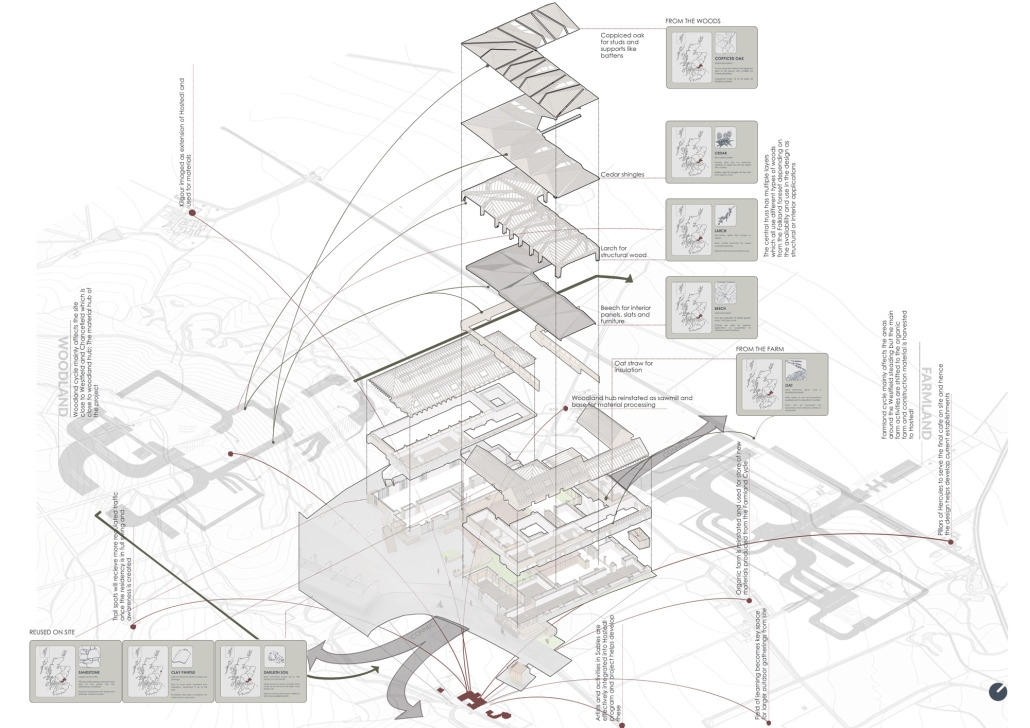

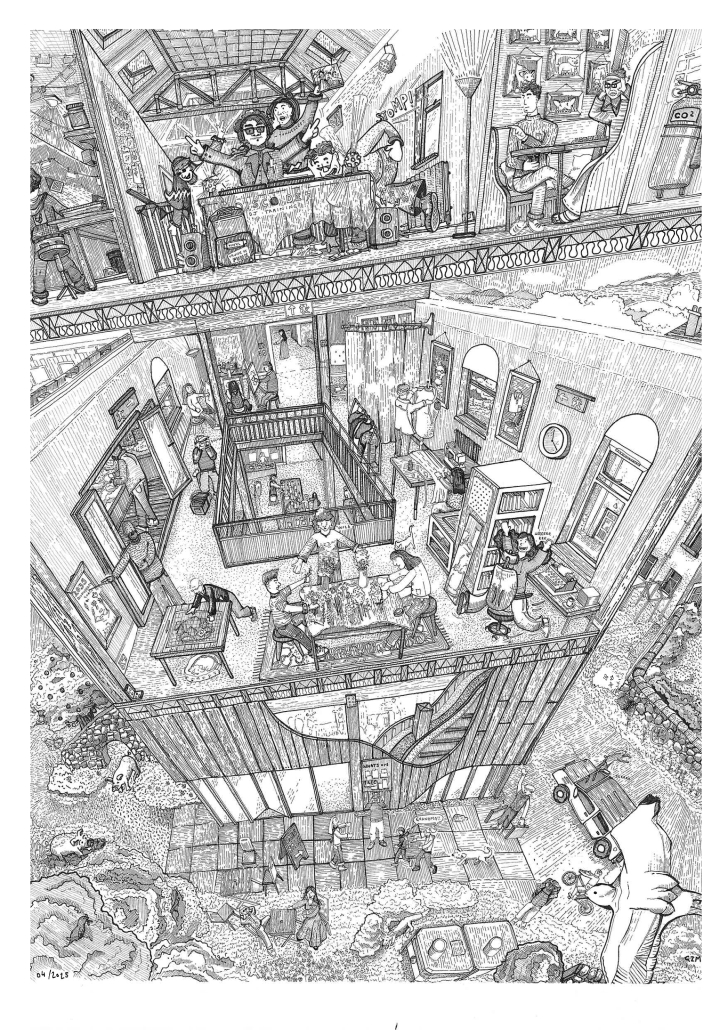

Hosted! The ReFrame Residency by Jahnavi Jayashankar, M.ArchD ’25

Oxford Brookes University | Advisors: Melissa Kinnear & Alex Towler

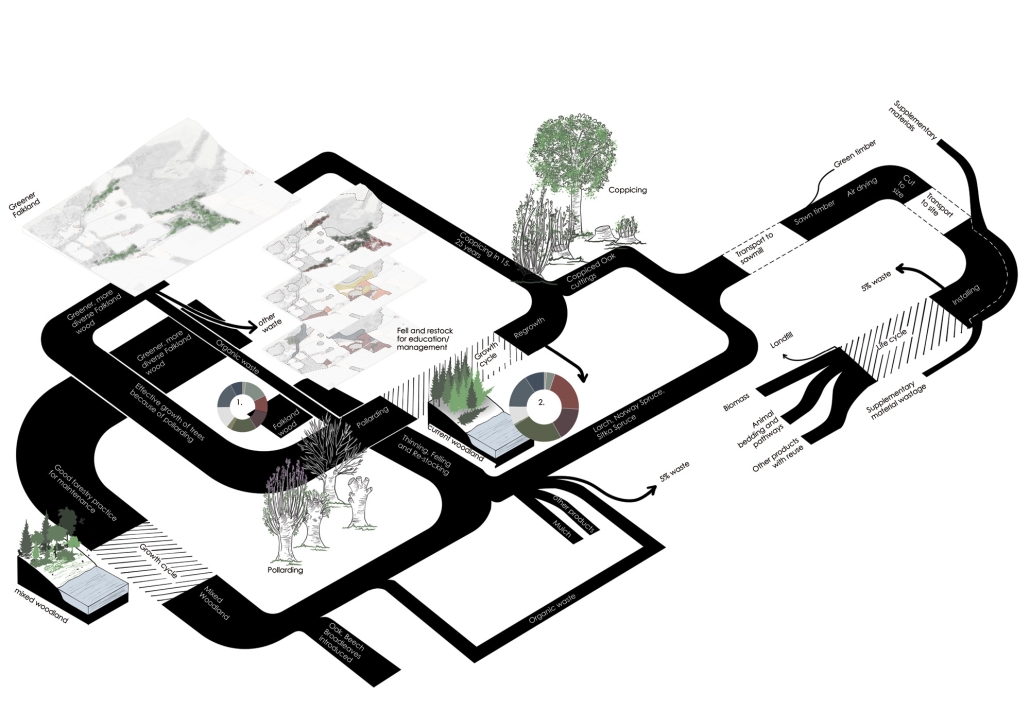

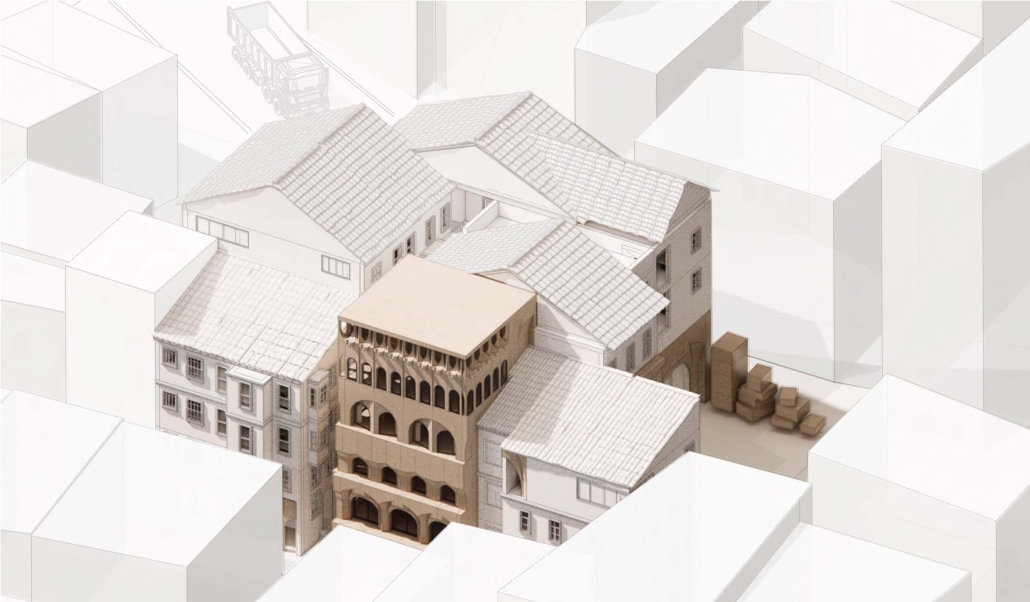

“Hosted!” is a regenerative retrofit project located in Falkland Estate, Fife, Scotland, which transforms a derelict farm steading into a vibrant, multifunctional residency. Rooted in regenerative design principles, the project positions architecture as a systems actualizer—an active agent working across ecological, cultural, and socio-economic systems to unlock the full potential of place.

Rather than responding solely to the client’s immediate needs, Hosted! emerges from a deep understanding of the land, its histories, and the relationships that shape it. The proposal integrates three core components: residential spaces, a gallery, and a series of workshops. These are not merely functional zones but mechanisms for participation, exchange, and knowledge generation. The residency invites multidisciplinary professionals to engage with the site over a term, after which their work is exhibited. The community then collectively selects one project to be developed further in a live workshop the following term. This cyclical process fosters collaborative learning and continuity.

The inaugural residency, ReFrame, explores regenerative material construction using locally sourced materials such as timber from the estate and straw from nearby fields. This phase functions as both material inquiry and community engagement, inviting local residents to co-create the space. By blurring the line between users and makers, Hosted! nurtures a sense of ownership and shared stewardship.

At its core, the project challenges traditional separations between design, construction, and occupation. It views architecture as a dynamic process—growing through iterative feedback, stakeholder reciprocity, and contextual responsiveness. Guided by regenerative frameworks, Hosted! values multi-capital exchanges and organizes resources holistically to catalyze systemic transformation.

Importantly, the project resists reductive sustainability metrics. It seeks not just net-neutrality but net-positive outcomes—restoring ecosystems, strengthening communities, and reactivating place-based identities. By mapping contextual systems, leveraging underused assets, and enabling circular practices, Hosted! demonstrates how design can act as a catalyst for healing and renewal.

In essence, Hosted! is more than a building retrofit—it is a regenerative strategy rooted in place. It reimagines architecture as a facilitator of co-evolution between people and environment, offering a model for how the built environment can transition from sustainability toward true regeneration.

This project won the MAKE Architects Award for Excellence in a M.ArchD Course.

Instagram: @impulsive._.art, @melissa.kinnear.9, @ds3_obu

UDC Culinary Science Building by Teneisha Brown, B.S. in Architecture ’25

University of the District of Columbia | Advisor: Dr. Golnar Ahmadi

As part of UDC’s strategic plan to revitalize its city campus and expand career-focused programming, the university has launched an innovative new Culinary Science program. Students were challenged to design a sustainable building on the Campus.

Instagram: @Golnarahmadi

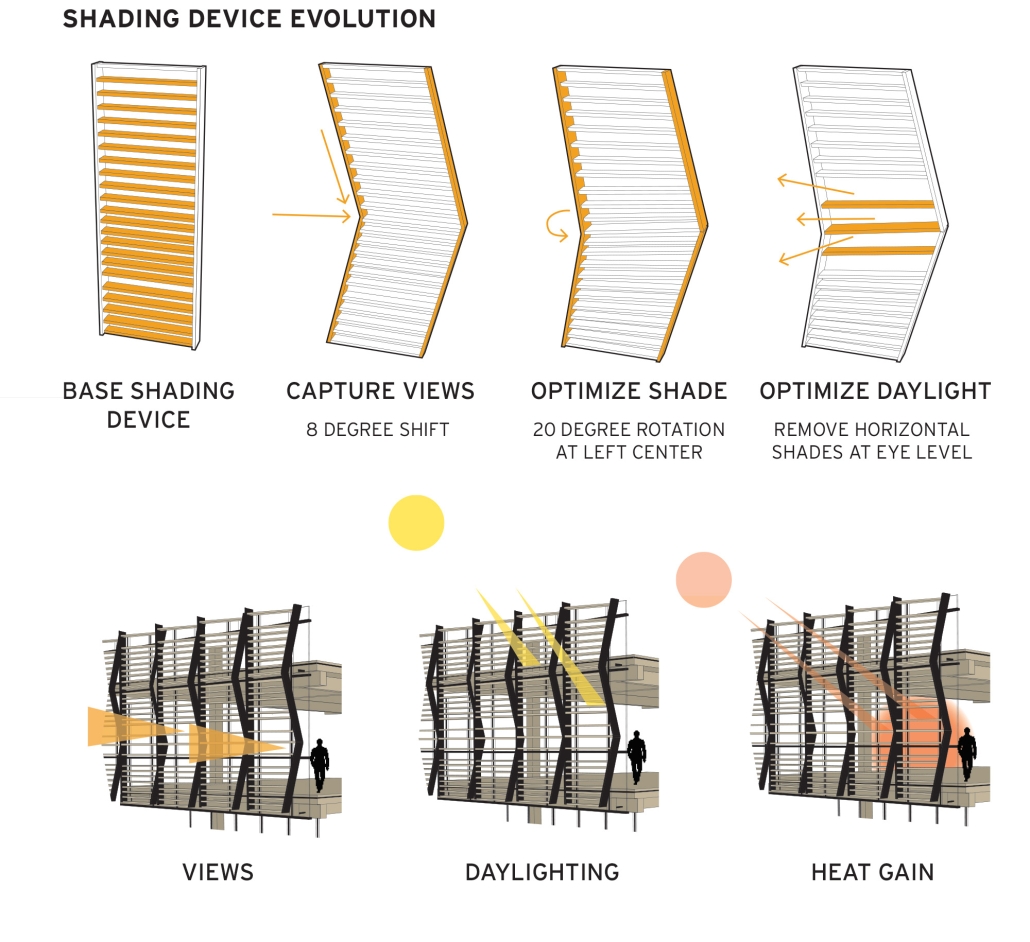

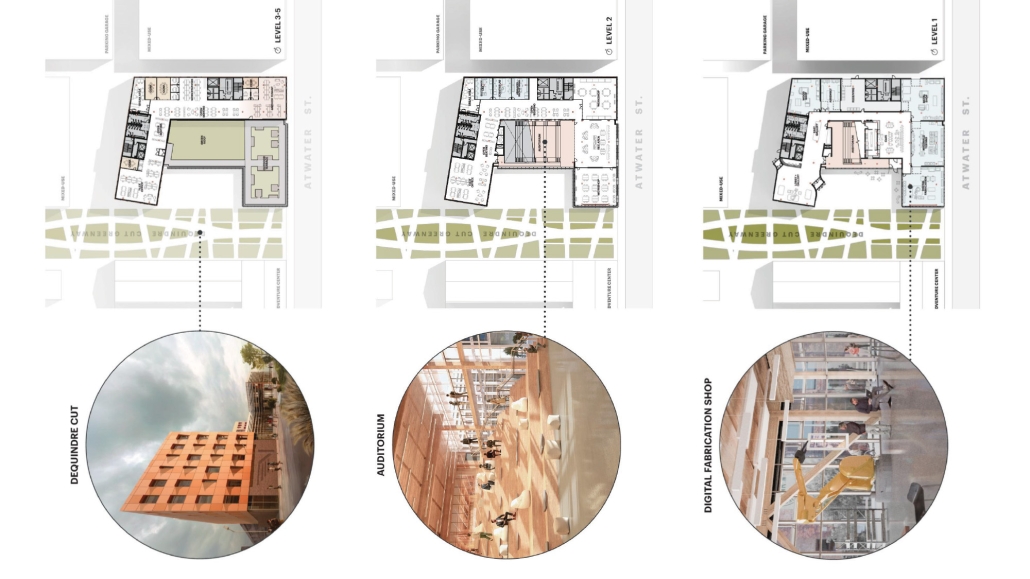

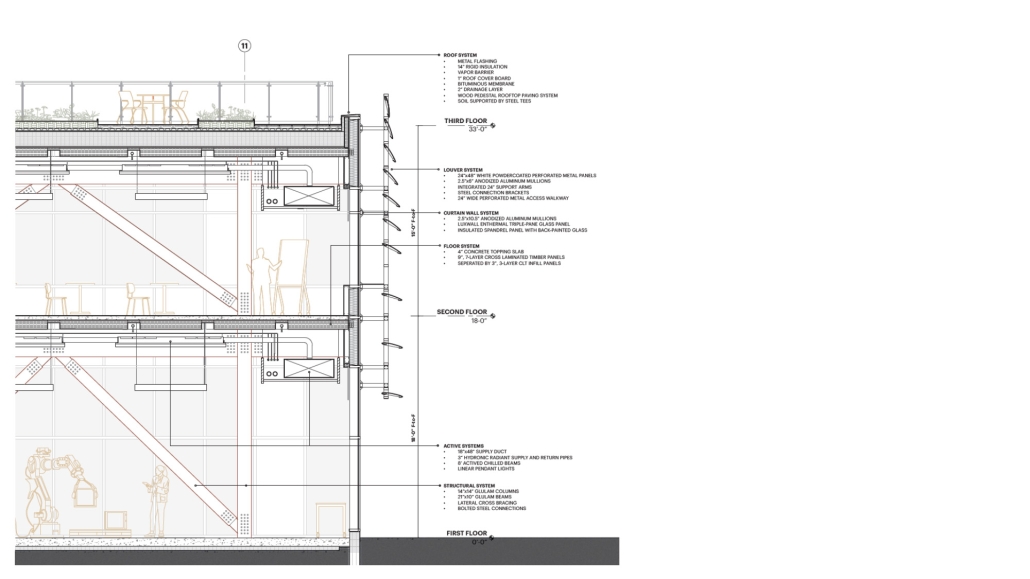

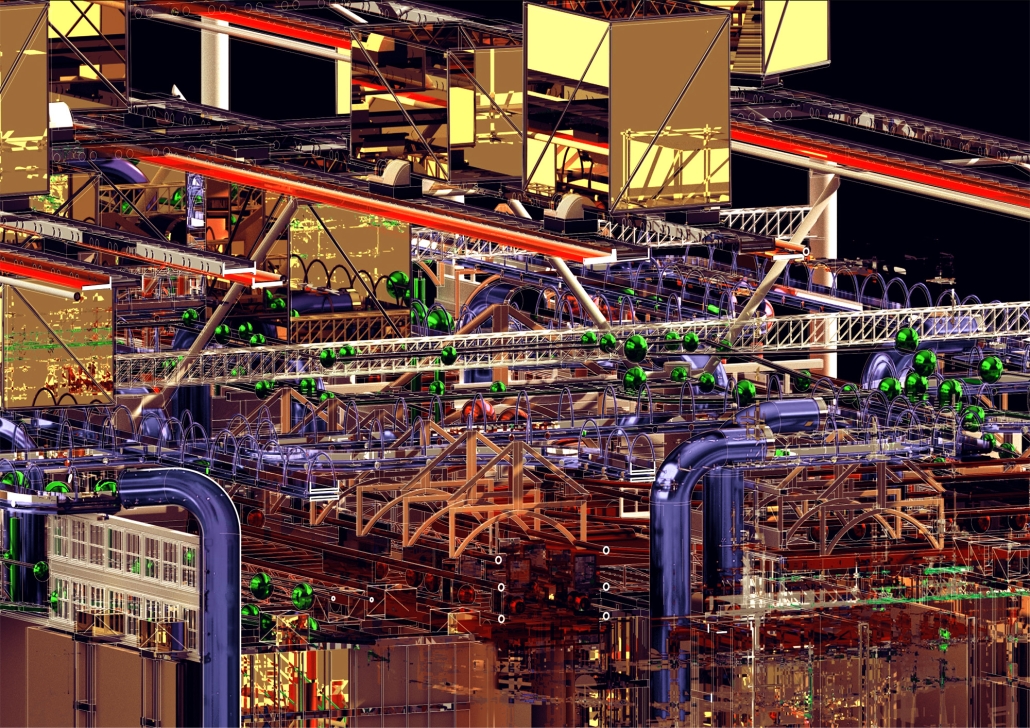

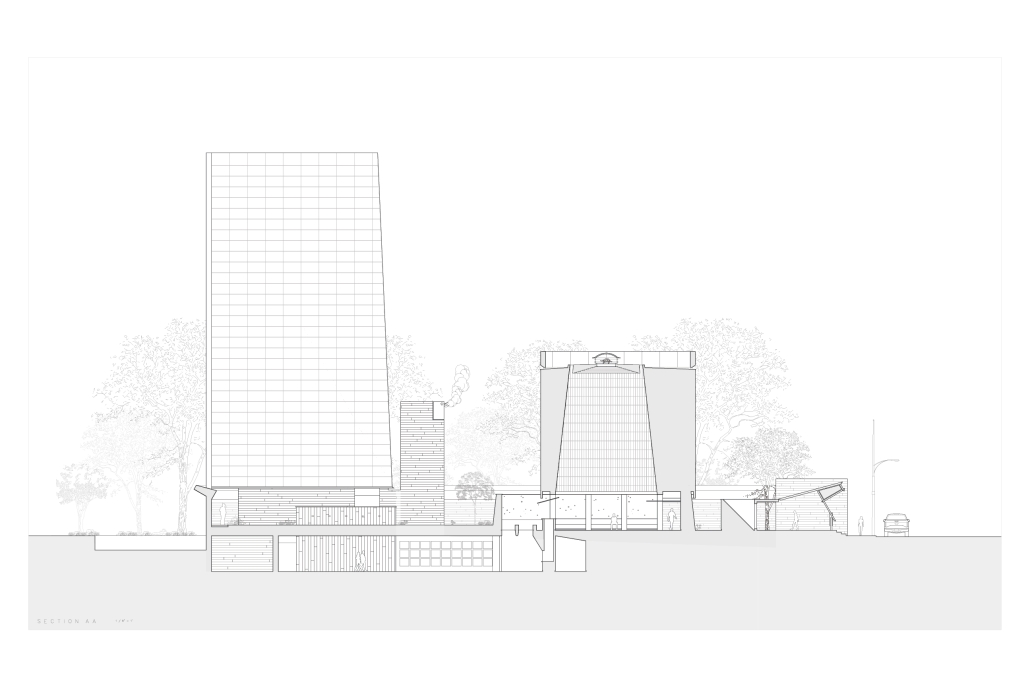

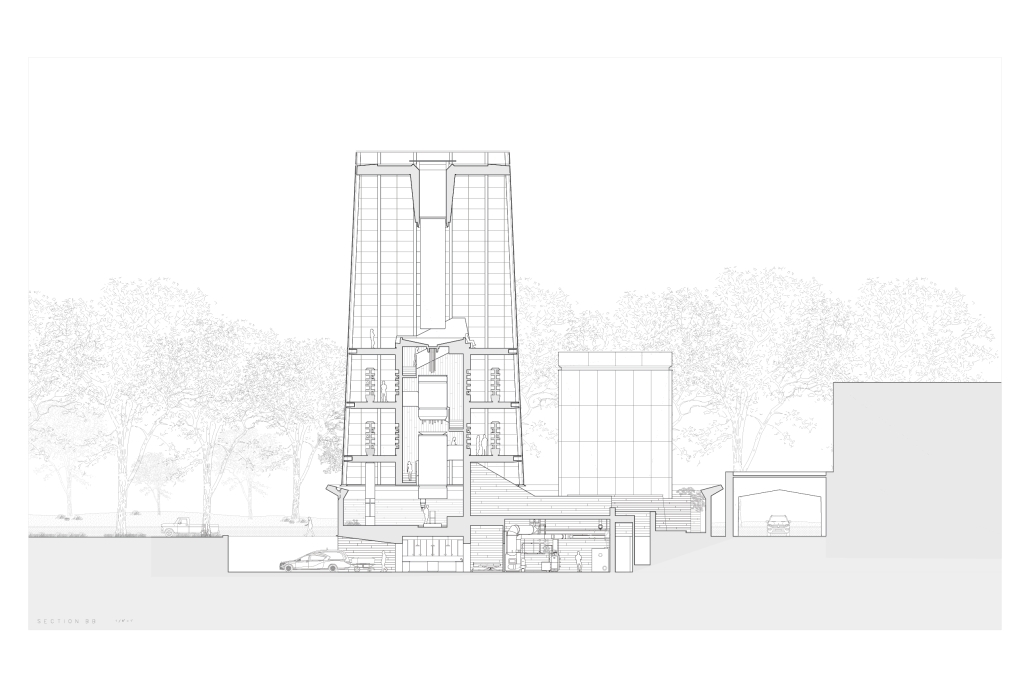

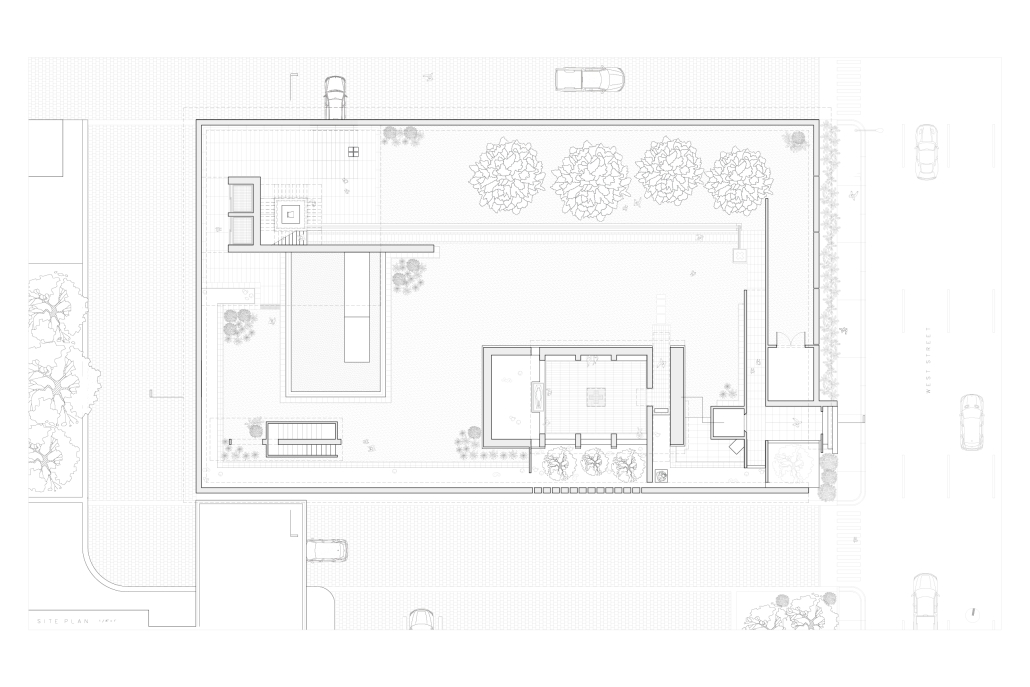

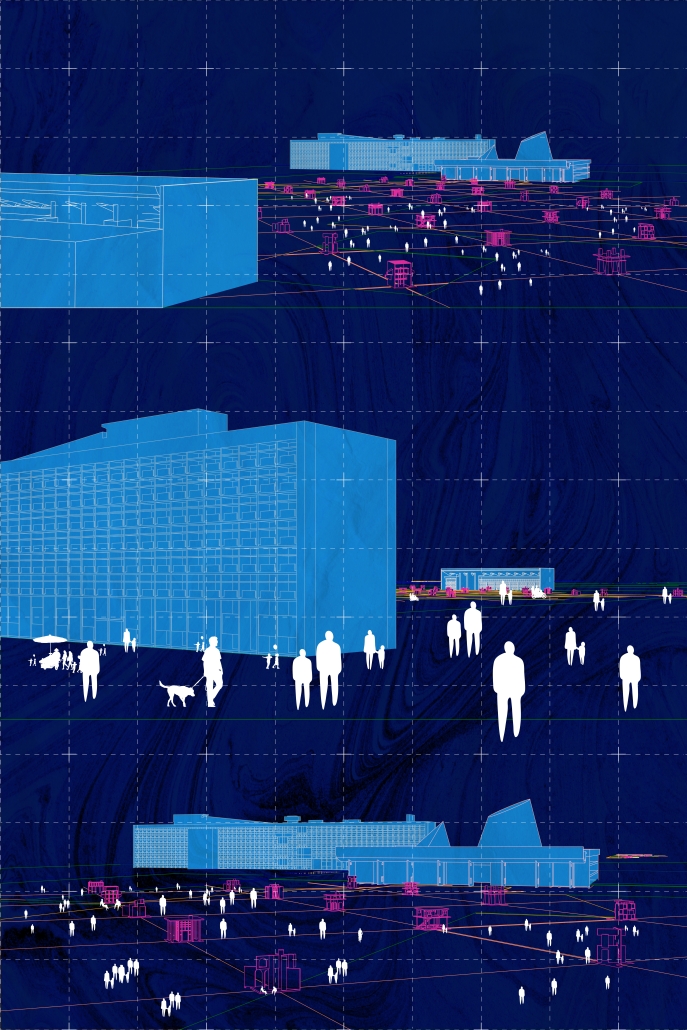

VLAB Detroit – Sustainable Business Incubator by Jumana Zakaria, Philip Jurkowski & George Smyrnis, M.Arch ’25

University of Detroit Mercy | Advisors: James Leach & Kristin Nelson

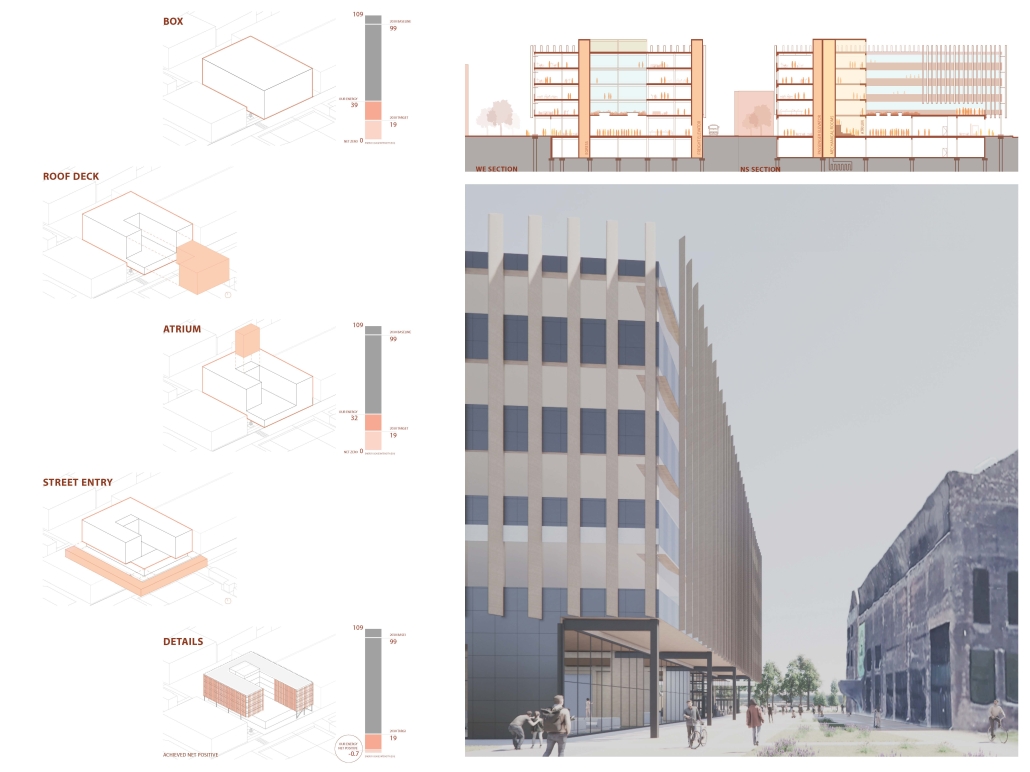

This new business incubator in the Rivertown neighbourhood is focused on propelling innovation in sustainable building. As a center of knowledge and development aiming to progress building systems into a low-carbon, net-zero era, the design of the building supports this philosophy. On the corner of Atwater Street and the Dequindre Cut greenway, the building is to be a productive space for tenants and a positive landmark in a vibrant community.

Adjacent to the Detroit Riverfront and Dequindre Cut is a valuable asset in creating a sense of connectivity and community within the building. The form opens to the southwest, allowing for daylighting, engagement with the two neighbouring paths, and good views to the connected public spaces, trails, and parks of the Detroit Riverfront. The form erodes inward on the west side, inviting entry from the Dequindre Cut, connecting to the riverfront and creating a central urban pocket.

Just as important as the community response is the need to address the well-being of visitors and tenants. A public entry gallery and auditorium [occupy] the ground floor while the open, flexible, daylit floor plates above ensure a high level of well-being and productivity for occupants. A gradient of adjustable social and working spaces, such as drop-in and permanent workstations and meeting rooms, breakout rooms, and lounges ensure that occupants have a comfortable and collaborative workplace. A combination of passive and active building systems, including hydronic heating and cooling, and geothermal heat pumps create a comfortable interior climate.

The priority of sustainability quietly underlines all design choices. As a model of progressive, environmentally-conscious design and construction, the building utilises a composite timber structure, deliberate building envelope design, renewable energy sources, and intelligent stormwater management. A green roof and outdoor terrace line the roof adjacent to the third-floor office spaces, functioning as part of the stormwater management system, an additional collaboration space, and a transitional view between the offices and the Detroit Riverfront. Integrating these strategies ensures a low embodied and operational carbon footprint while creating a beneficial interior environment.

Instagram: @george.smyrnis

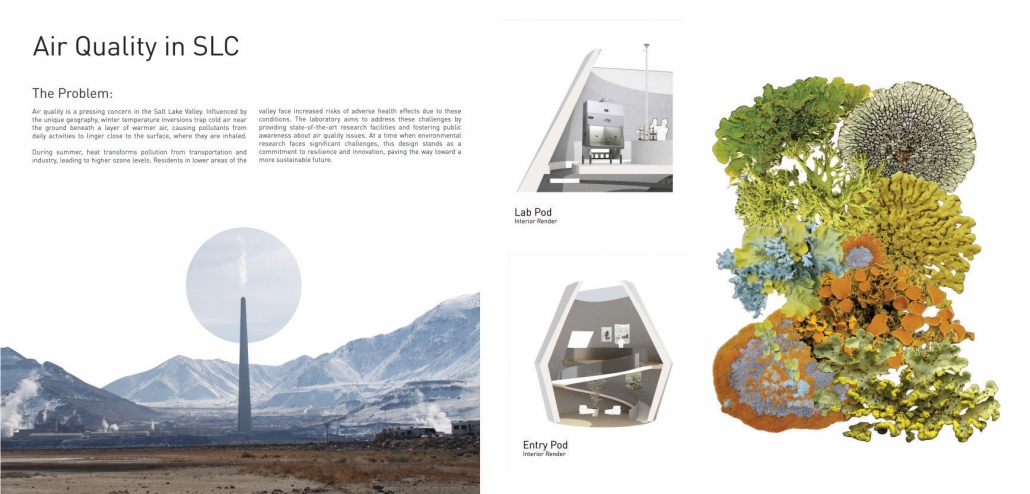

Lichen Air Lab by Olivia Etz, B.S. in Architectural Studies (BSAS) ’25

University of Utah | Advisor: Kateryna Malaia

Embedded within the historic Judge Building in downtown Salt Lake City, the Lichen Air Lab research center serves as one node in a statewide network of air quality monitoring facilities. The facilities in this system operate at varying scales, from a central headquarters to smaller satellite pods designed for fieldwork, with each representing a different stage of the lichen’s growth. Lichen, a resilient symbiotic organism formed by fungi and algae, thrives in diverse climates and is found throughout the Salt Lake Valley. The fungus provides structural support, while the algae produce energy through photosynthesis, a partnership that mirrors the lab’s relationship with the host building. The Judge Building provides support while the research lab cleans the air, benefiting both.

Instagram: @olivia_etz, @katemalaia

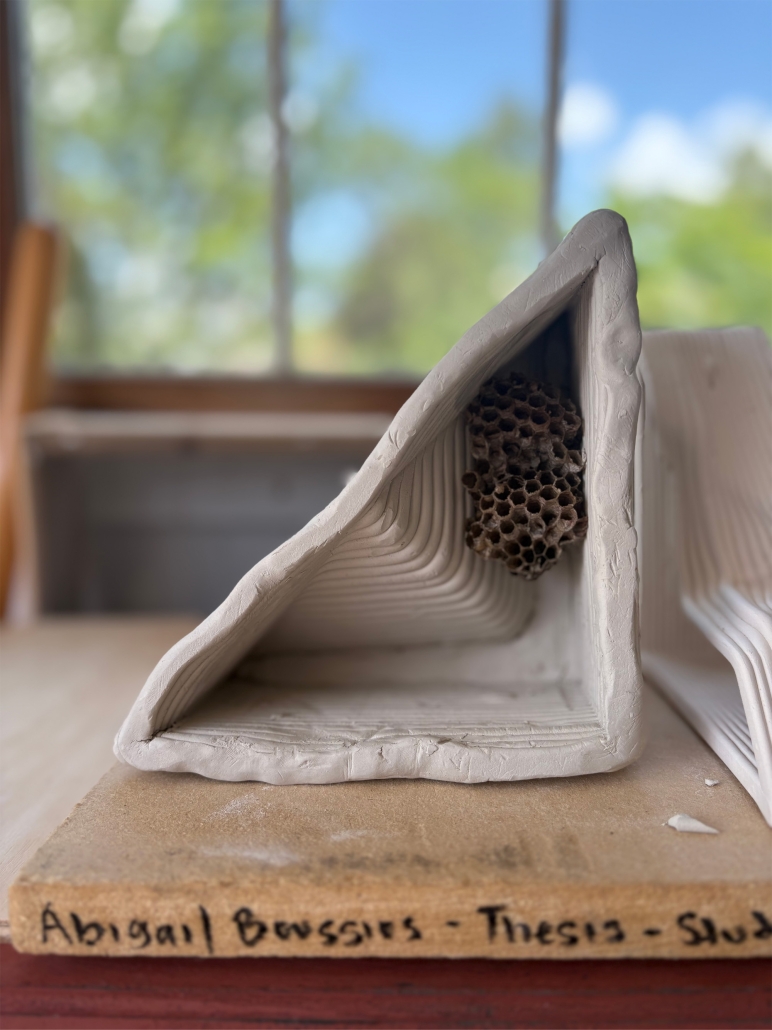

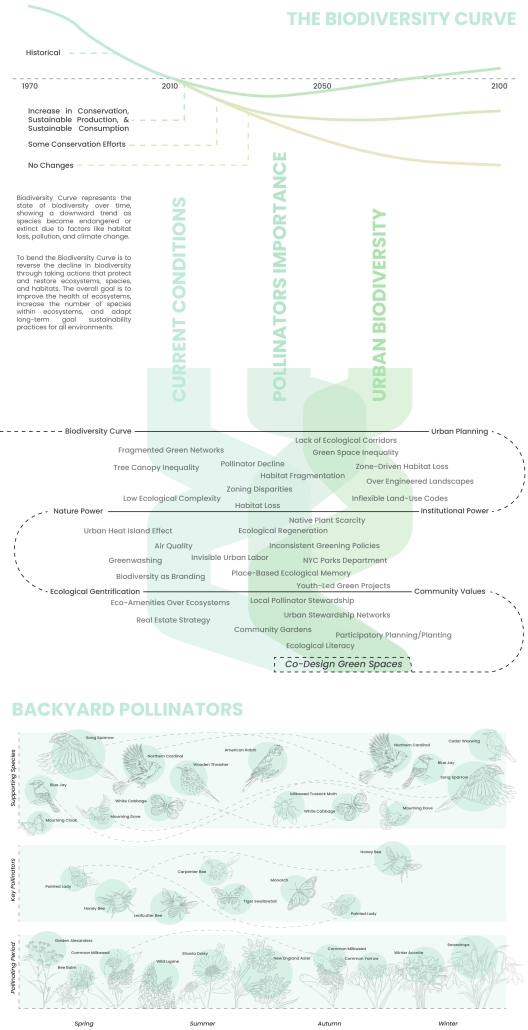

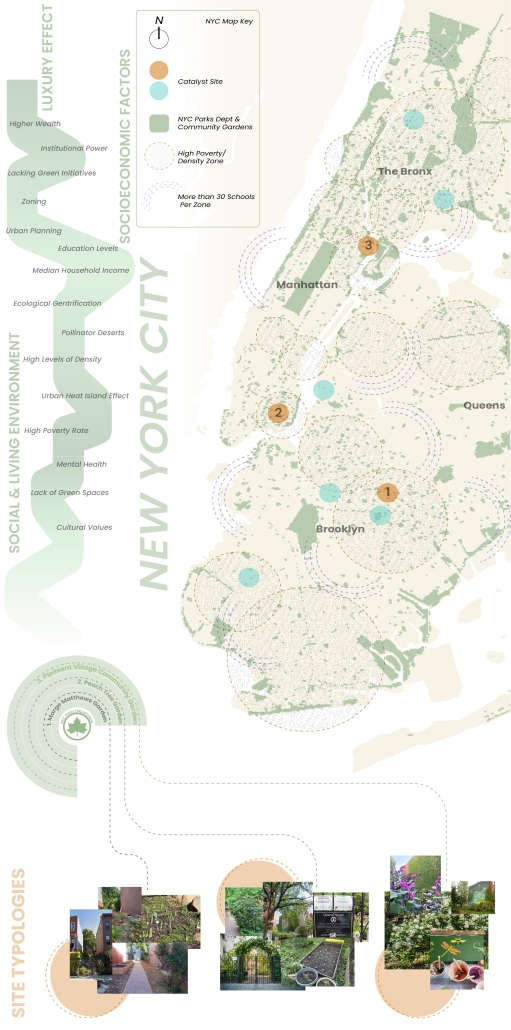

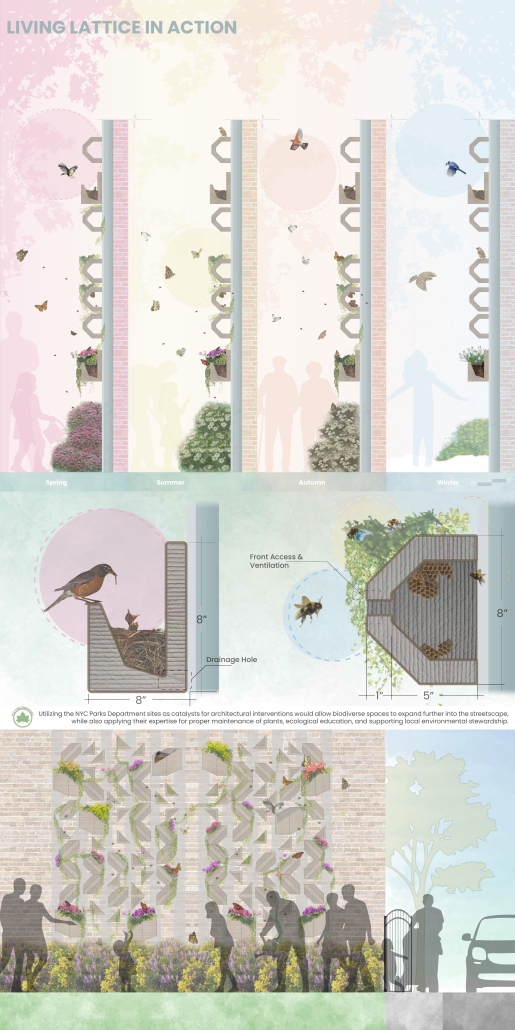

Living Lattice: In Between The Living and Social Environment by Abigail Rose Boussios, M.Arch ’25

Kean University | Advisors: Stephanie Sang Delgado & Sarah Ruel-Bergeron

[This] thesis research investigates how the living and the Social Environment in our urban fabric interact alongside issues such as the Biodiversity Curve, Luxury Effect, and a lack of access to green spaces in high-density/low-income areas.

My design proposal is to install a 3D printed clay modular facade system that would create a new habitat for pollinators within “In Between” spaces (areas that are pockets of space between buildings) owned by the NYC Parks Department. There are several “in between” community gardens that flourish in these spaces and revitalize the areas through both community and ecological stewardship. Collaborating alongside the NYC Parks Department Parks/Community Gardens as catalysts for architectural interventions would not only allow biodiverse spaces to expand from the in-between buildings to further into the streetscape, but also apply their expertise for proper maintenance of plants, ecological education, and supporting local environmental stewardship.

[Using] 3D printing clay as the facade material not only is eco-friendly, reusable, and long-lasting, but also allows for modularity and community participation in their Living Lattice installation. Shaped by the input and creativity of the surrounding community, this flexibility not only encourages participation, but also ensures that each installation reflects the unique identity and needs of its neighborhood.

NYIT’s Fabrication Lab granted me access to use their Kuka Bot Clay Extruder to produce 1:1 successful proof of concept fragment modules. I also fabricated a 1:1 2’x3’ mock-up of the installation on a wall to show the expected interactions of nature with the facade intervention.

“Living Lattice” is more than a facade intervention—it’s a call to action. It reclaims these in-between urban spaces and revitalizes them as active participants in the ecological and social healing of our cities. By bridging the Living and the Social, we not only nurture biodiversity but also develop a deeper sense of belonging, care, and responsibility among urban communities. Through modular design, collaboration, and stewardship, we have the power to reshape the city from the ground up—one fragment, one bird, one seed at a time — real change begins in the spaces in between.

This project received the Michael Graves College School of Public Architecture Masters of Architecture Thesis Award

Instagram: @abigail_b.10, @abigail.b.designs, @keanarch, @stepholope

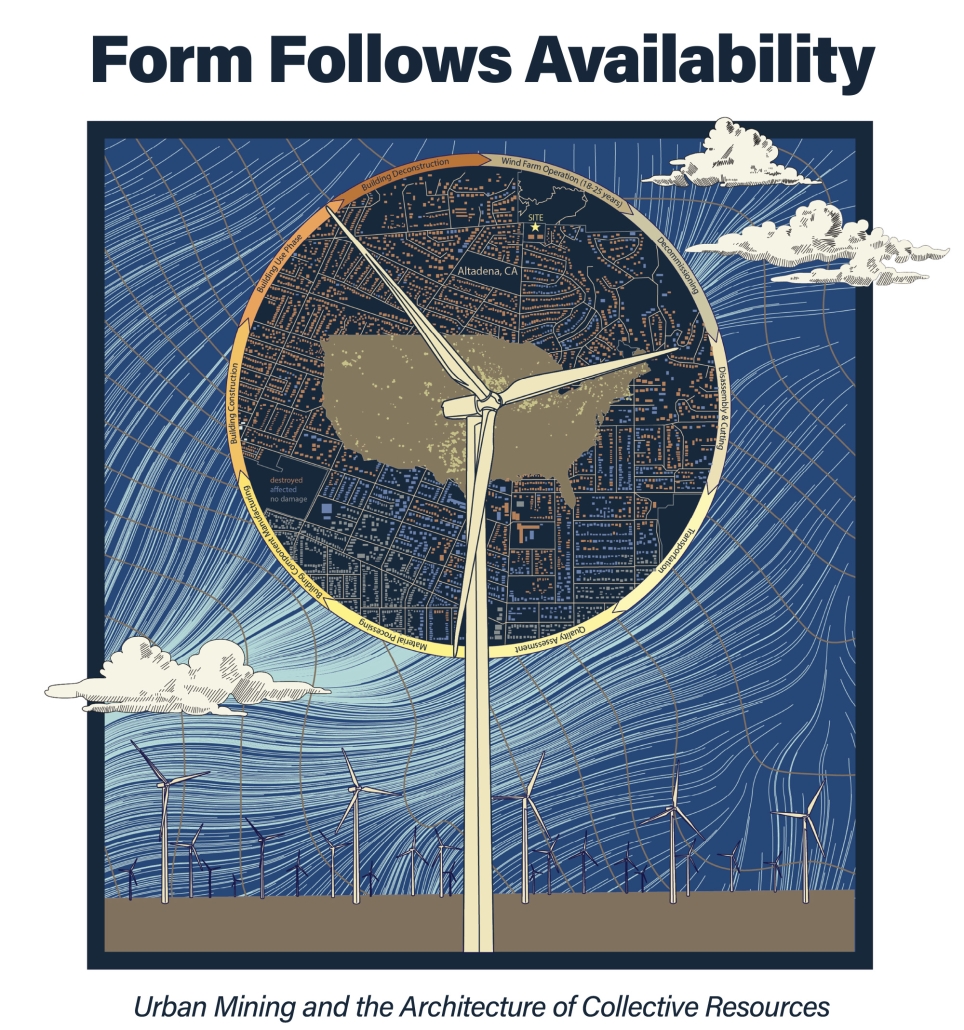

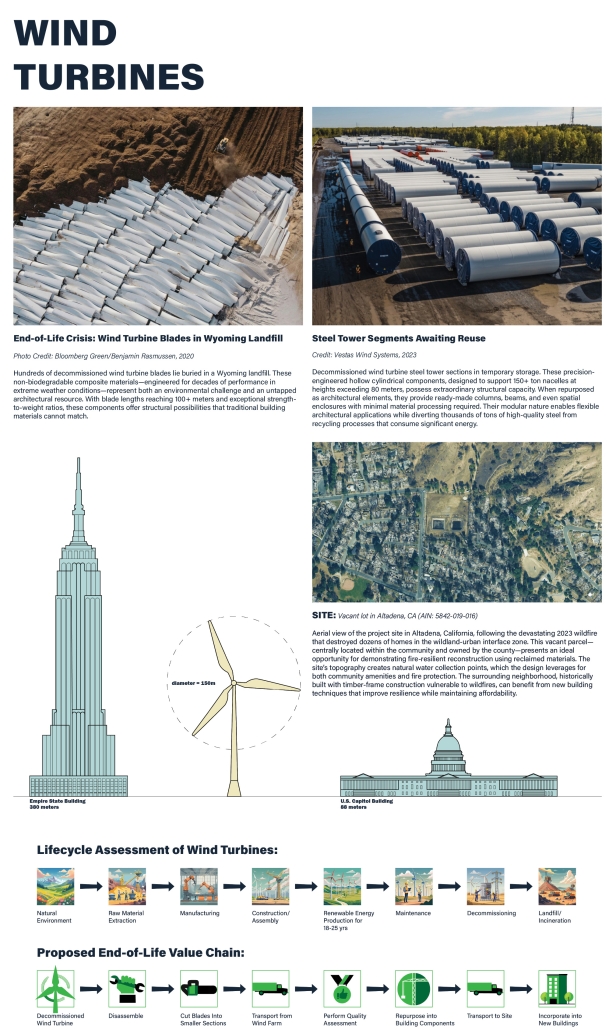

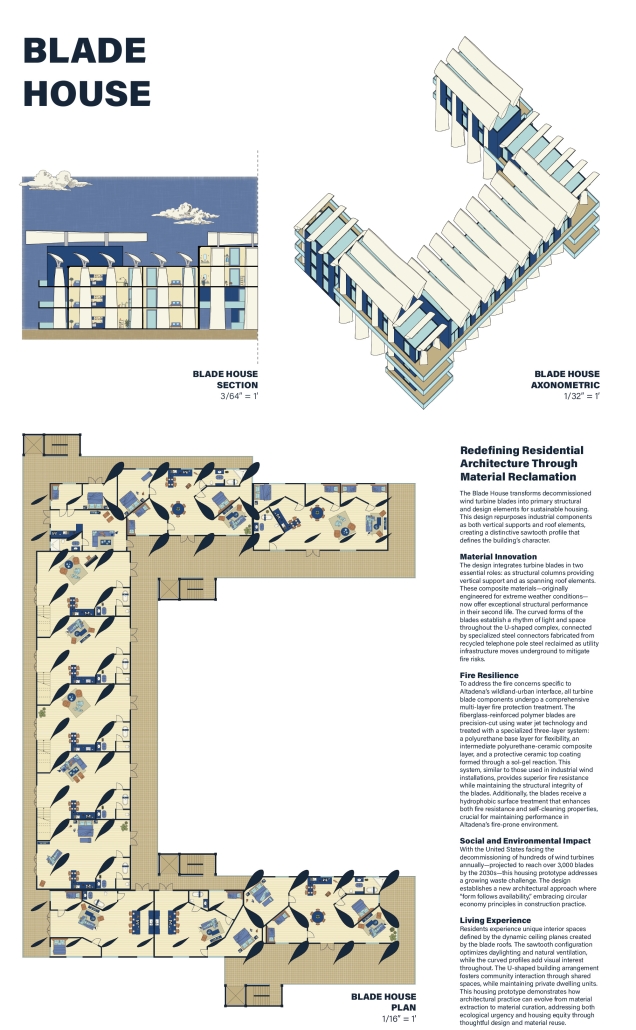

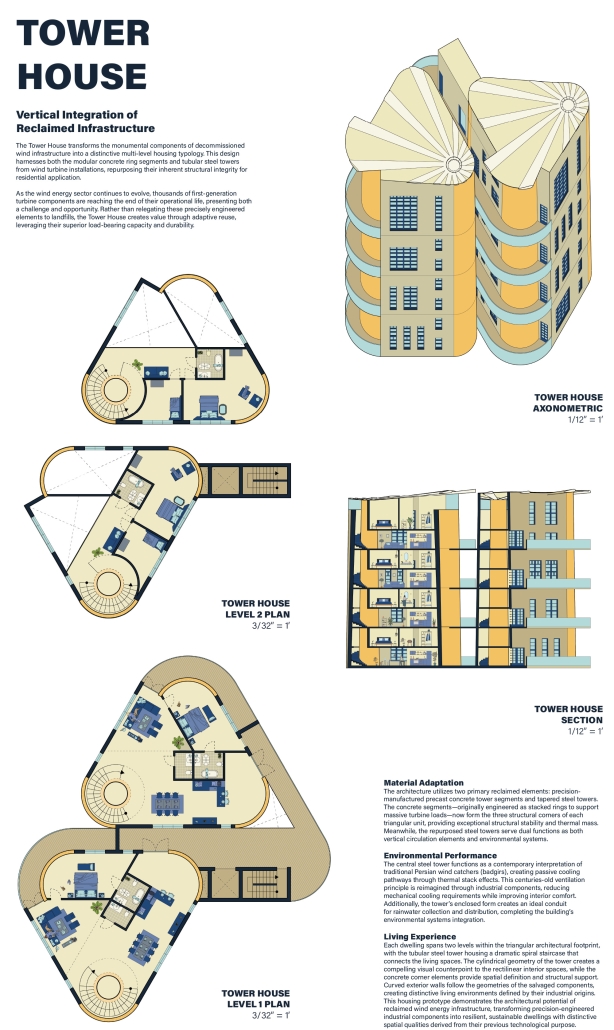

Form Follows Availability – Urban Mining and the Architecture of Collective Resources by Anna Simpson, M.Arch ’25

University of Southern California | Advisor: Sascha Delz

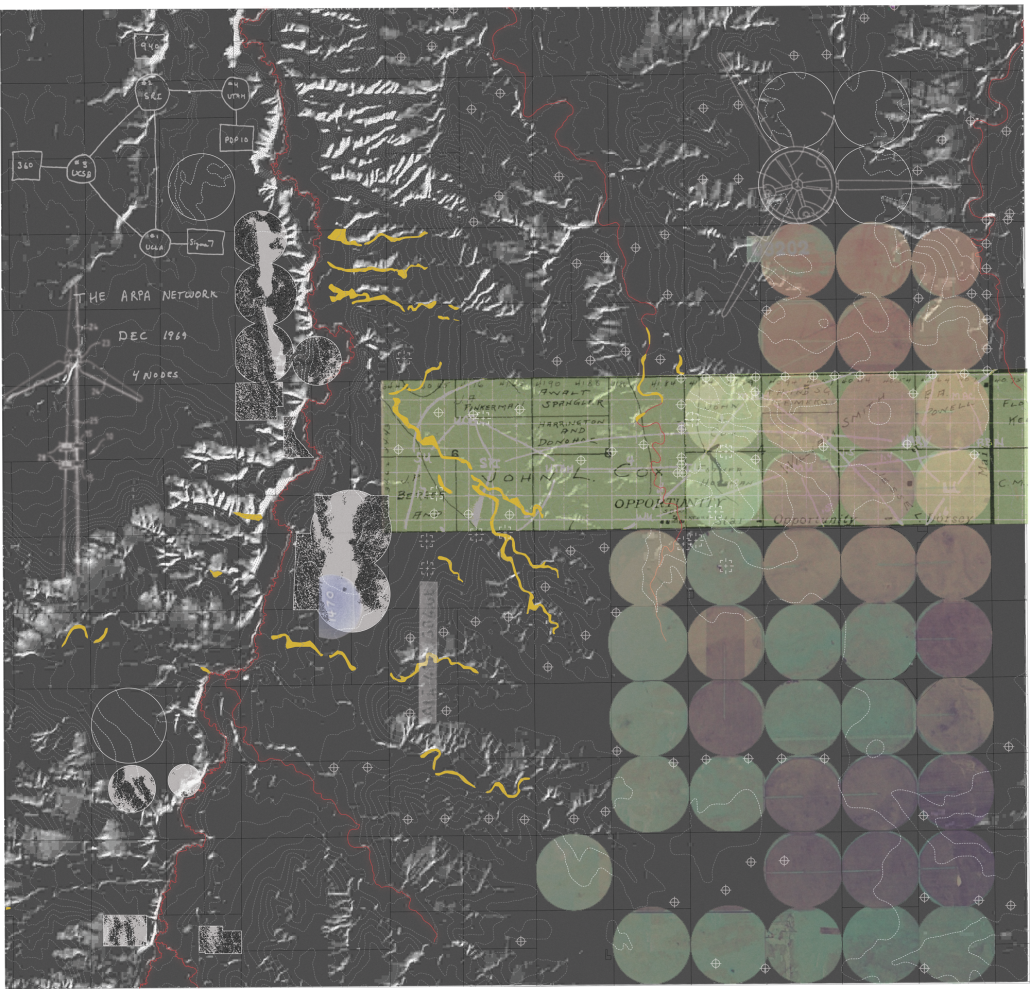

Since humans first built shelters, architectural form has been dictated by material availability—a fundamental principle that modern construction practices have abandoned through unsustainable extraction cycles. This thesis reclaims and reframes this logic for contemporary practice through a comprehensive urban mining framework that reconceptualizes industrial waste as collective architectural resources. Using decommissioned wind turbines as a primary case study, it demonstrates how systematic material recovery can address both environmental sustainability and housing affordability while responding to immediate climate-related disasters. With 70,800 wind turbines currently operating in the United States, and projections showing over 3,000 blades reaching end-of-life annually by the 2030s—potentially generating 2 million tons of waste in the U.S. alone by 2050—this framework establishes a scalable system for material recovery and redistribution.

Drawing on Elinor Ostrom’s understanding of common-pool resource management, the approach creates a collectively managed material bank where recovered industrial components become accessible building materials for affordable housing developments on city-owned land. Situated on a vacant lot in Altadena, California—a neighborhood devastated by recent wildfires—this proposal directly addresses the urgent need for recovery and reconstruction. The site plan follows the natural topographic water flow to prevent mudslide damage, directing water into an existing abandoned reservoir. By reintegrating engineered composites into residential architecture, the framework reduces construction costs while advancing material-driven design methodologies where form again follows availability. This shift from extraction to curation fundamentally transforms architectural practice, reconnecting it with its historical roots while addressing contemporary challenges of sustainability, waste management, housing accessibility, and climate resilience in urban environments.

Instagram: @coop_urbanism

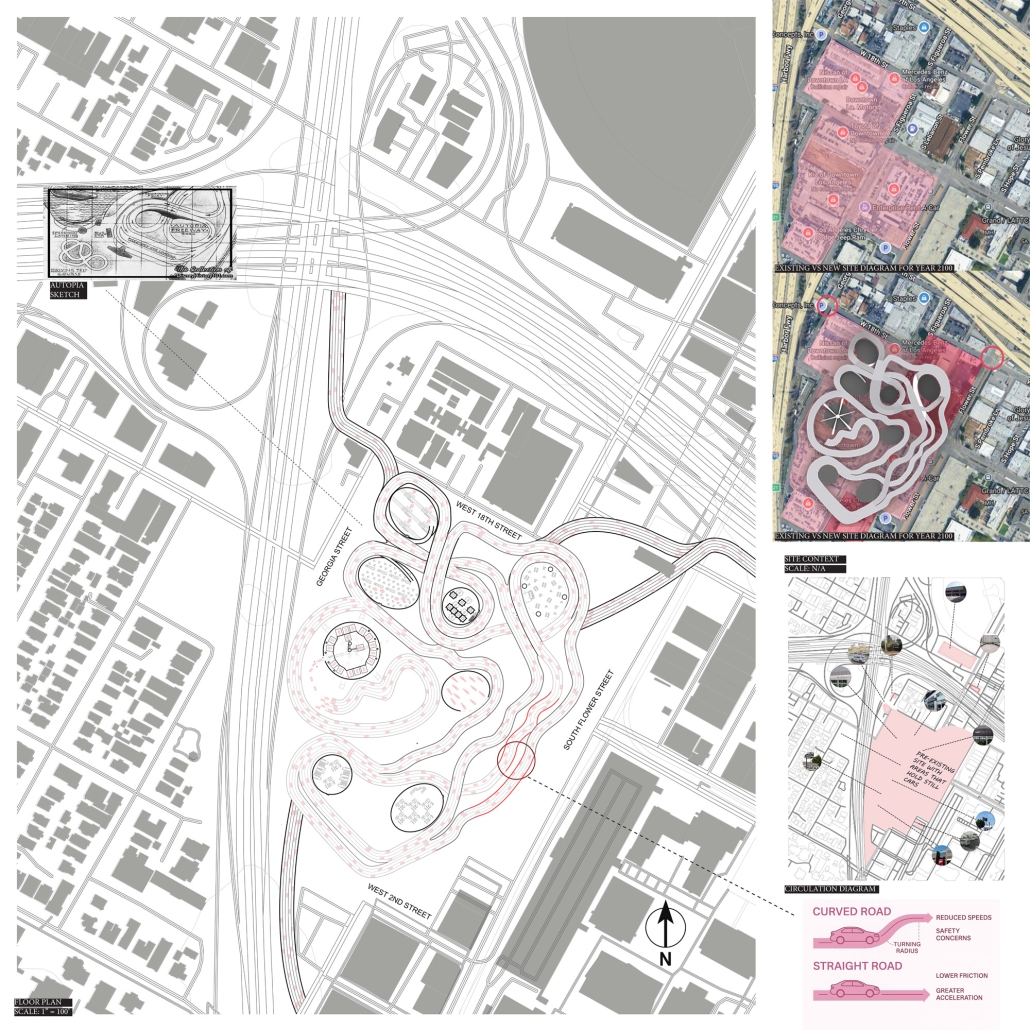

Fleetwave: A Ride to the Future by Meena Afshar, B.Arch ’25

Woodbury University | Advisor: Gerard Smulevich

Imagine a city where streets breathe again, free from traffic, noise, and smog. “FleetWave” is that vision brought to life: a subscription-based network of self-driving, all-electric vehicles designed to replace personal car ownership in Los Angeles. At the heart of this proposal is a simple idea: mobility as a shared resource, not a private burden. Traditional cars sit idle most of the time, eating up space and polluting the air. FleetWave reimagines transportation as clean, efficient, and community-oriented. Powered by renewable energy and charged wirelessly, including from embedded roadways and vertical wind turbines, Wave cars operate 24/7. Riders book them by subscription, choosing from four tiers based on needs like range or comfort. Inside, they’re more than cars, mobile workspaces, social pods, or quiet retreats. Outside, they reduce traffic, reclaim land from parking lots, and restore green space to the city. AI synchronization prevents congestion and improves safety. FleetWave turns urban mobility into an experience of collective progress. It’s not just about getting from point A to B; it’s about creating a city that moves with you, not against you. Los Angeles is just the beginning. The future doesn’t just arrive; it rolls in, quietly and fully charged.

Instagram: @meanuuhh, @g_smulevich

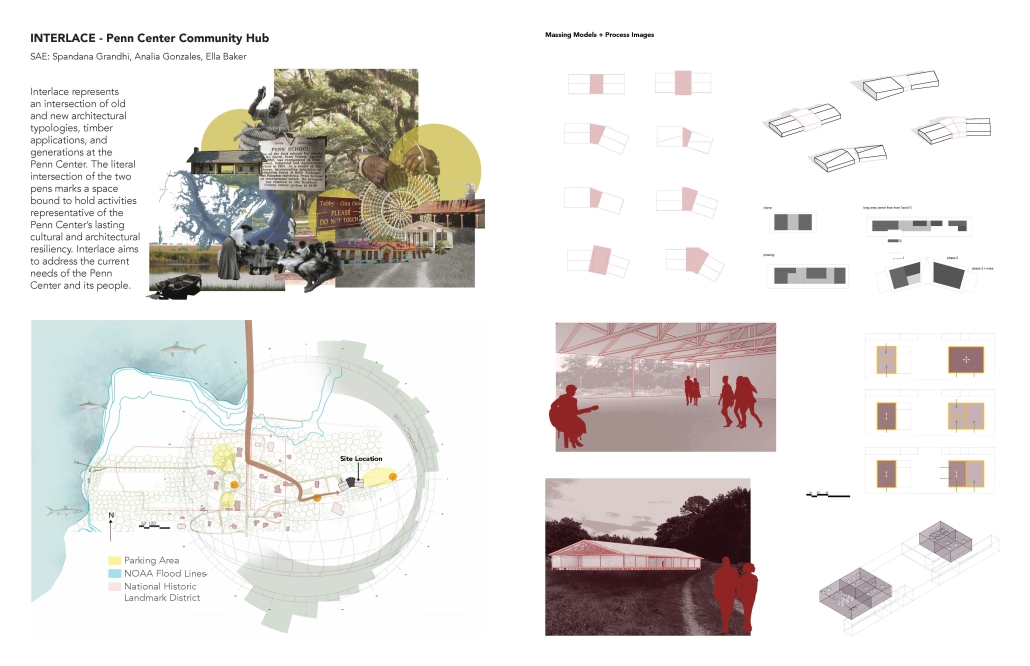

INTERLACE – Penn Center Community Hub by Spandana Grandhi, Analia Gonzales & Ella Baker, BS in Architecture ’25

Georgia Tech | Advisor: Danielle Willkens

“Interlace” represents an intersection of old and new architectural typologies, timber applications, and generations at the Penn Center. The literal intersection of the two pens marks a space bound to hold activities representative of the Penn Center’s lasting

cultural and architectural resiliency. Interlace aims to address the current needs of the Penn Center and its people.

Instagram: @georgiatech.arch, @archDSW

Harboring Sustainability: Designing a Resilient Future for Sag Harbor by Kyra Duke & Melina Tsinoglou, B.Arch ’25

New York Institute of Technology | Advisor: Dongsei Kim

Adding affordable housing in Sag Harbor would give younger generations the opportunity to live and work in the community where they grew up or work, thereby fostering a more diverse, year-round population rather than a seasonal, retirement-focused town.

Rising housing costs are displacing young professionals, artists, and essential workers, including much-needed teachers. Therefore, an expanded affordable housing initiative could enable this population to establish their careers, which would additionally support local businesses and contribute to Sag Harbor’s cultural and economic vitality.

Additionally, this project demonstrates how well-planned dense housing combined with performative infrastructure in high flood-risk areas can offer wetland restoration, elevated pathways, and flood-resistant public spaces. These features help protect the coastline by functioning as a natural barrier against rising sea levels and storm surges.

Instead of resisting unavoidable environmental changes, adopting adaptive design strategies could slow erosion, enhance water absorption, and create functional public spaces that enable Sag Harbor to grow sustainably over the next 80 years, thereby becoming a model of responsible and sustainable coastal living.

Instagram: @dongsei.kim

Stay tuned for Part XIV!