Building Diversity Within Austin's Architecture Community

(via KUT.org)

When you think of architecture, you probably think about the style and functionality of a building. You may not always think about the people who drew up the plans. But their perspectives can help shape the way our cities look. In Austin, African-American women are hoping to diversify the field of architecture.

A couple weeks ago, Devanne Pena made a surprising discovery.

“I just became a licensed architect,” Pena said. “I found out that I am the second black woman to be licensed in Austin, Texas altogether, which is nuts.”

Pena was keeping her eye on a directory of African-American architects maintained by The University of Cincinnati, but that directory is an unofficial record. We turned to some official record-keepers to see if Pena was really the second black female architect currently working in Austin.

Glenn Garry with the Texas Board Of Architecture Examiners said Pena is set to become the third black woman architect licensed in Austin after some standard administrative procedures, but there could be even more that aren’t accounted for.

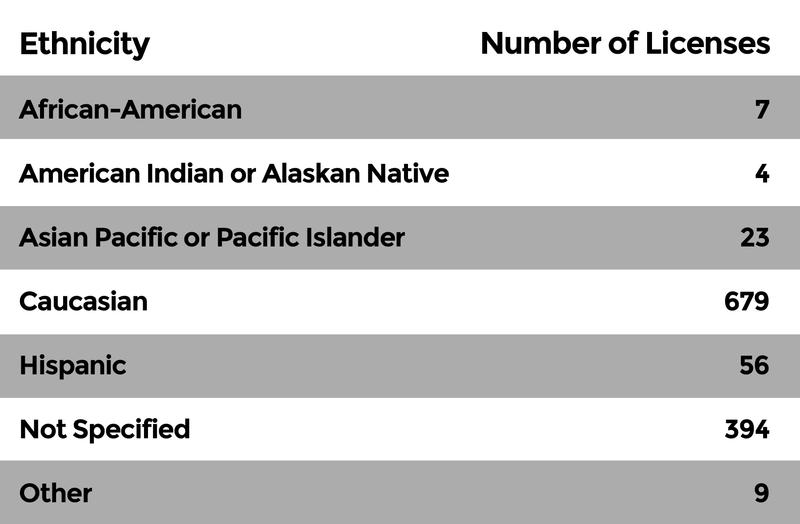

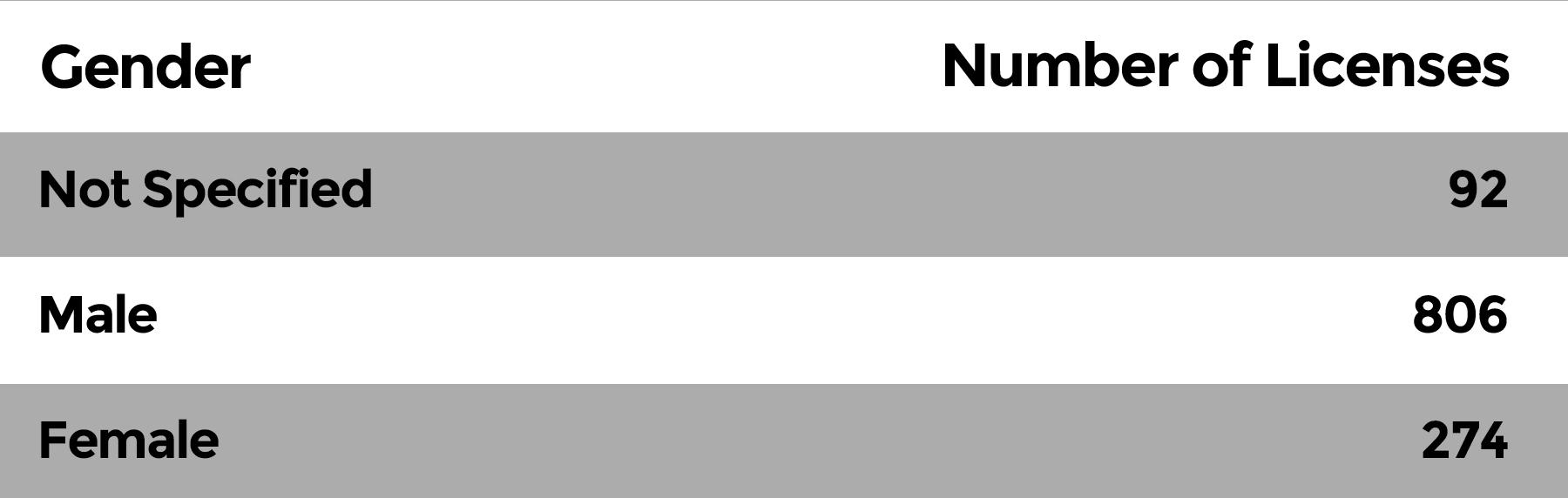

“So it looks like Ms. Pena is almost correct,” Garry said. “Our database has a field for whether you’re male or female, for what your race or ethnicity is, stuff like that. Those fields are totally optional though, so we have a lot of people who don’t answer any of that stuff, so we can’t – we don’t know.”

Still, the data does point to an overall lack of diversity in the field. Out of the more than 1,100 licensed architects in Austin, only seven reported their race as African-American.

You may be thinking, why does any of this matter? What difference does it makes if the person designing a building is a man, a woman, or a person of color? We posed that question to Donna Carter, the first black woman architect on record to be currently licensed in Austin. “The form can be very, very important to how a community and a culture survives,” Carter said.

You may be thinking, why does any of this matter? What difference does it makes if the person designing a building is a man, a woman, or a person of color? We posed that question to Donna Carter, the first black woman architect on record to be currently licensed in Austin. “The form can be very, very important to how a community and a culture survives,” Carter said.

Donna Carter, the first practicing black female architect in Austin, says architecture provides an outlet for cultural expression and community-building.

“The form can be very, very important to how a community and a culture survives,” Carter said.

To Carter, architecture is more than just technical design and planning. It’s a mode of creative expression, a way of defining your community and your idea of home.

“In many, many urban situations, 10 o’clock, 11 o’clock at night the streets are bustling,” she said. “There are little kids out on the street. They’re out on the front porch, it’s hot inside, everybody’s kind of out. To me, the very presence of front porches without huge gates in front of them, to me, that’s very welcoming.”

Both Carter and Pena agreed that a lack of minority voices can have a lasting impact on our built environment. Take Austin’s 1928 Master Plan, for example, which segregated the city by creating a “negro district.” Black residents were relegated to the area east of I-35, an area that’s now rapidly gentrifying. Pena thinks we are still feeling the effects of that planning decision, with thousands of black residents leaving East Austin in recent years.

“It’s kind of desolate in my opinion,” she said. “People who are originally from here can’t move in, and it’s hard to put a plan together on how to have that mode of expression, to have that ability to sit out on their porch.”

The architecture industry, however, seems to be taking notice.

Earlier this month, UT’s School of Architecture launched a new initiative to diversify its faculty, calling race and gender one of the most pressing issues facing the profession. Andrea Roberts is one of the program’s first fellows. She’s gearing up to teach new courses on race and development.

“I like to look at it in a way where we, instead of saying, ‘These are the deficits that we have in African-American communities and they’re under attack,’ that is absolutely in many ways true, but we have all of these assets,” Roberts said. “We have all of these skills and this history that we need to bring to the fore to help us to protect and honor these communities.”

Donna Carter is looking forward to seeing how initiatives like UT’s shape the future of architecture and planning. For now, she said, she’s happy to welcome Devanne Pena into the next generation of black women architects.

—