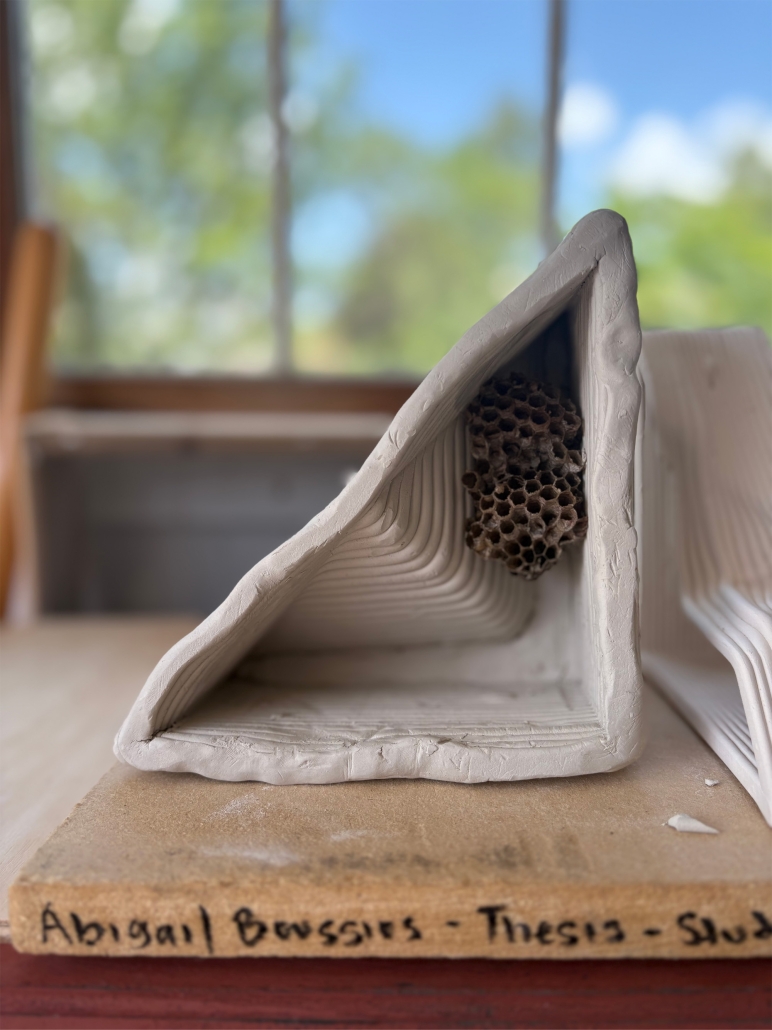

#ModelMakers: Audrey Cherek

Today’s edition of #ModelMakers features Audrey Cherek, a fourth-year undergraduate student at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln. Scroll down to learn more about Audrey’s style, along with her advice for fellow students!

Name:Audrey Cherek

School: University of Nebraska – Lincoln

Degree Program:Bachelor of Science in Design of Architecture

Year in School: Fourth Year Undergraduate

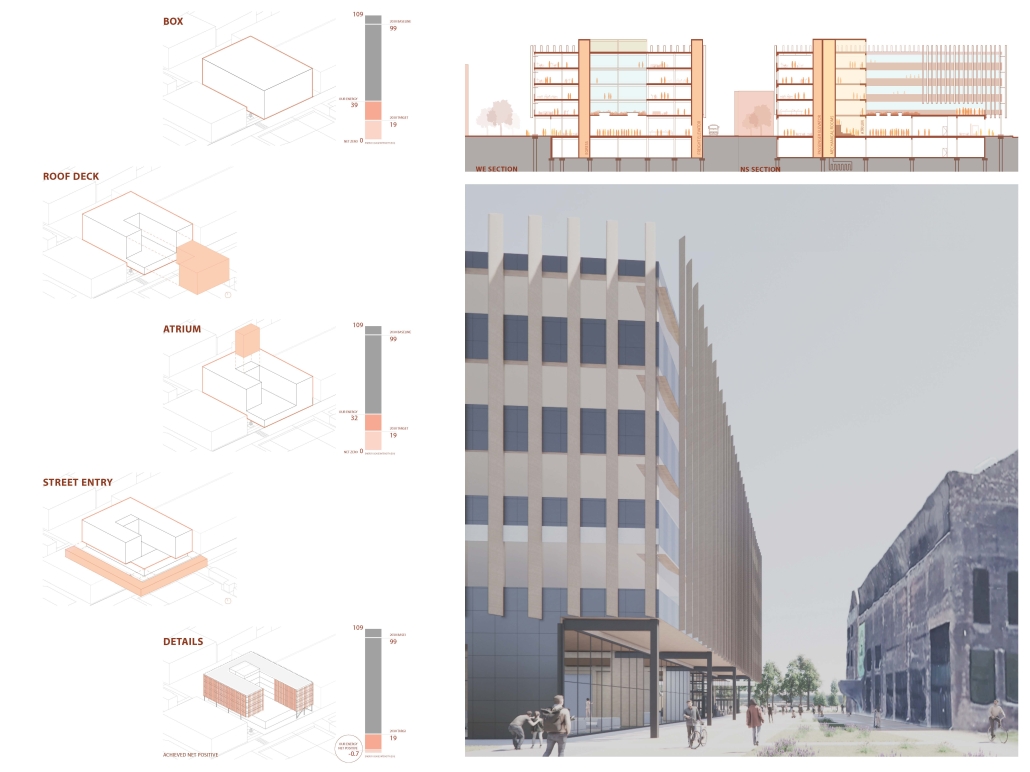

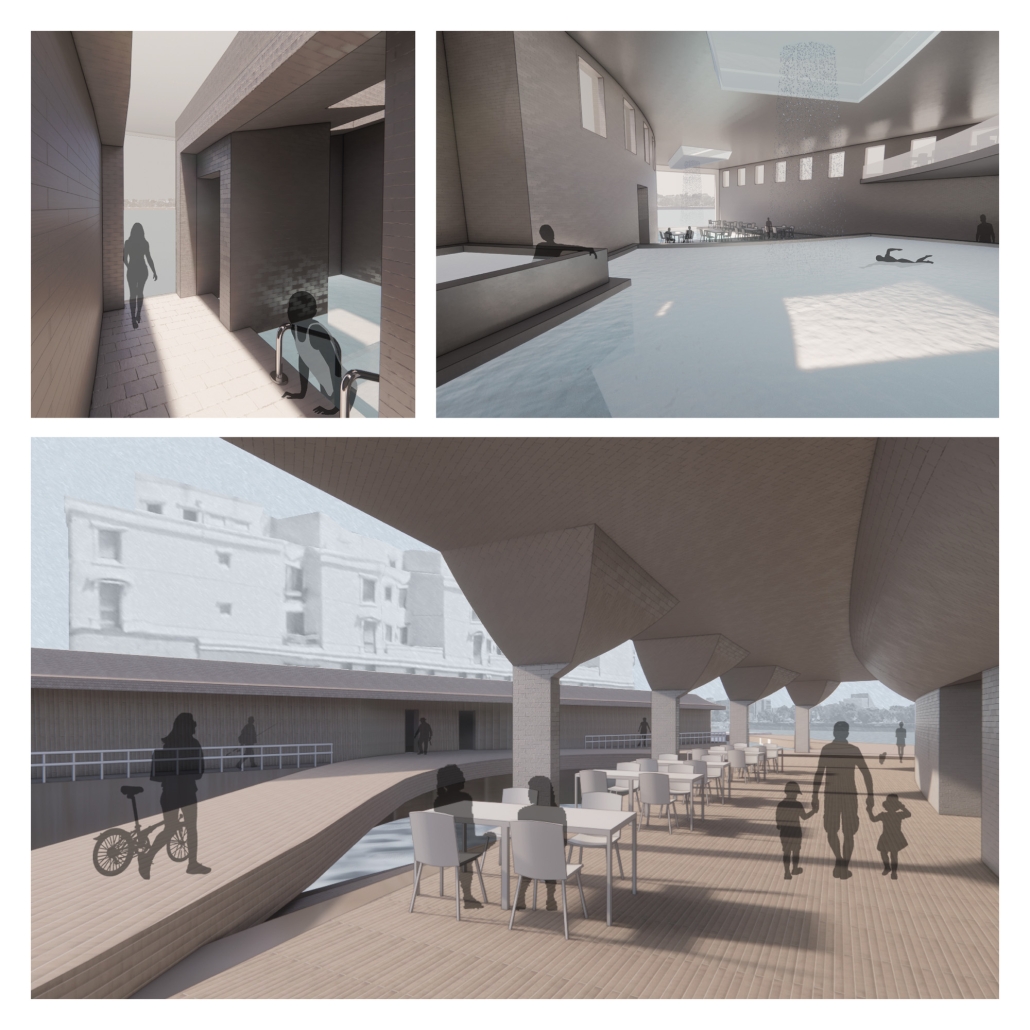

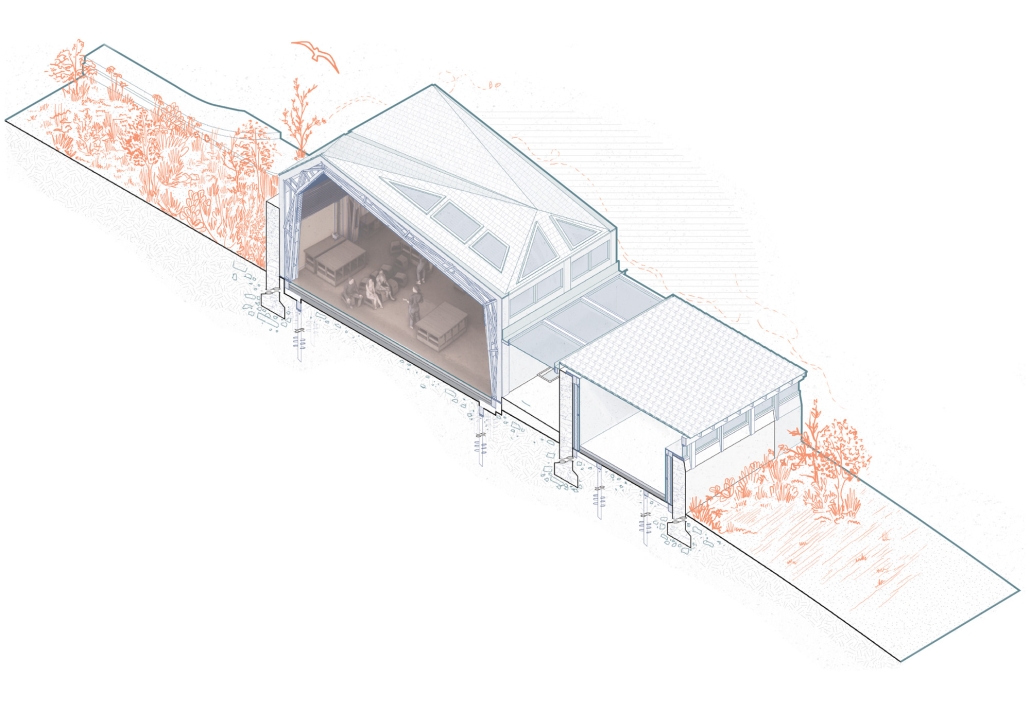

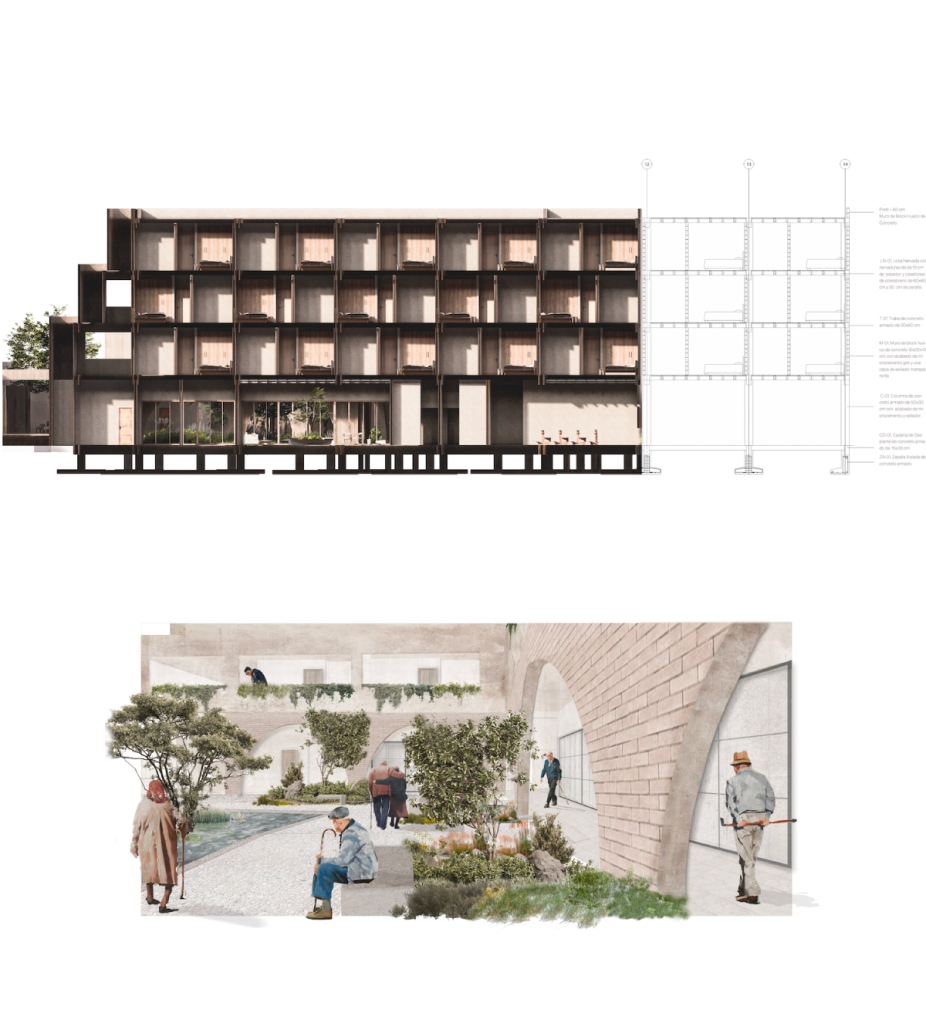

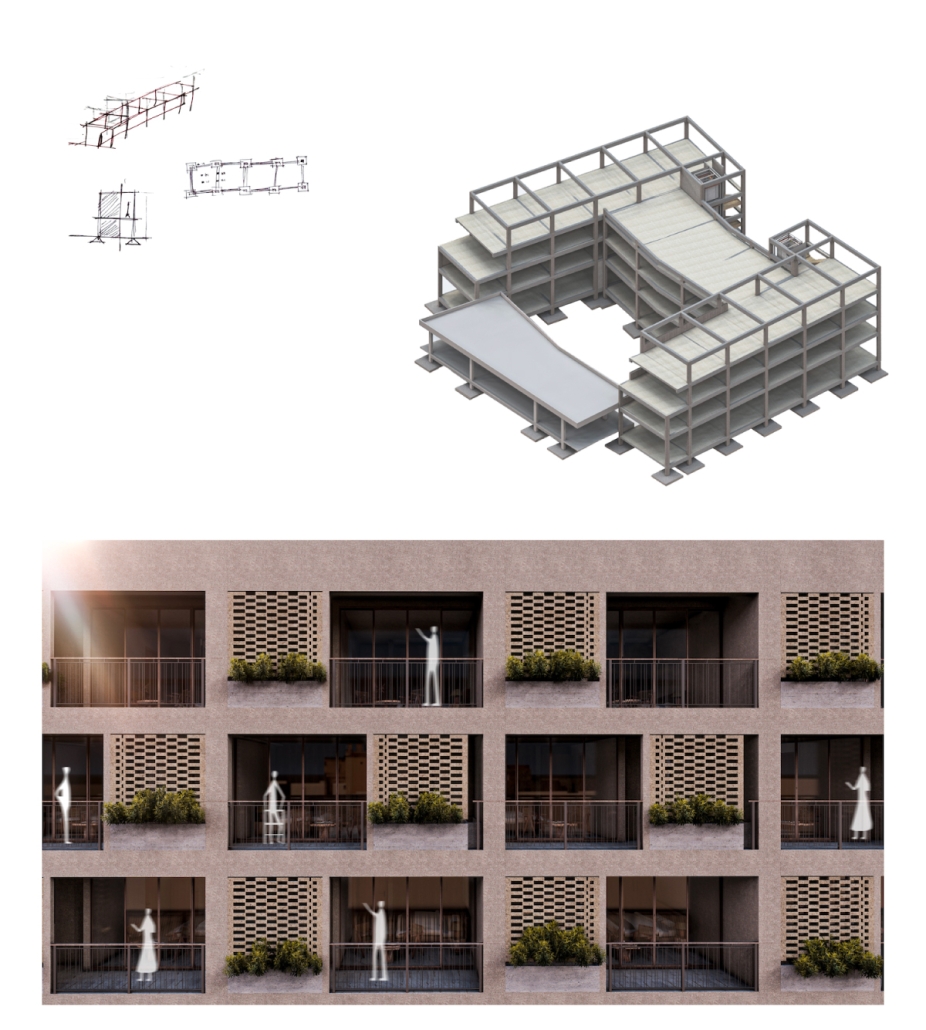

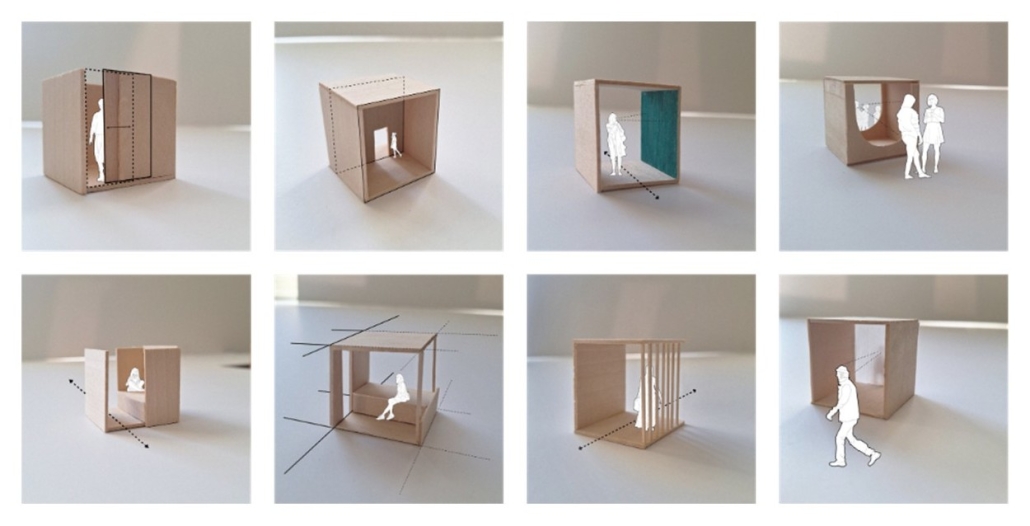

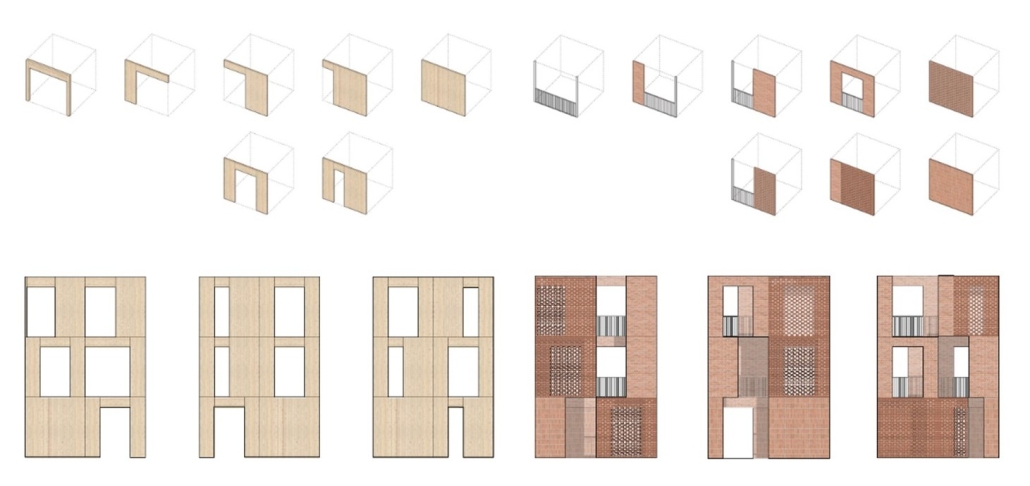

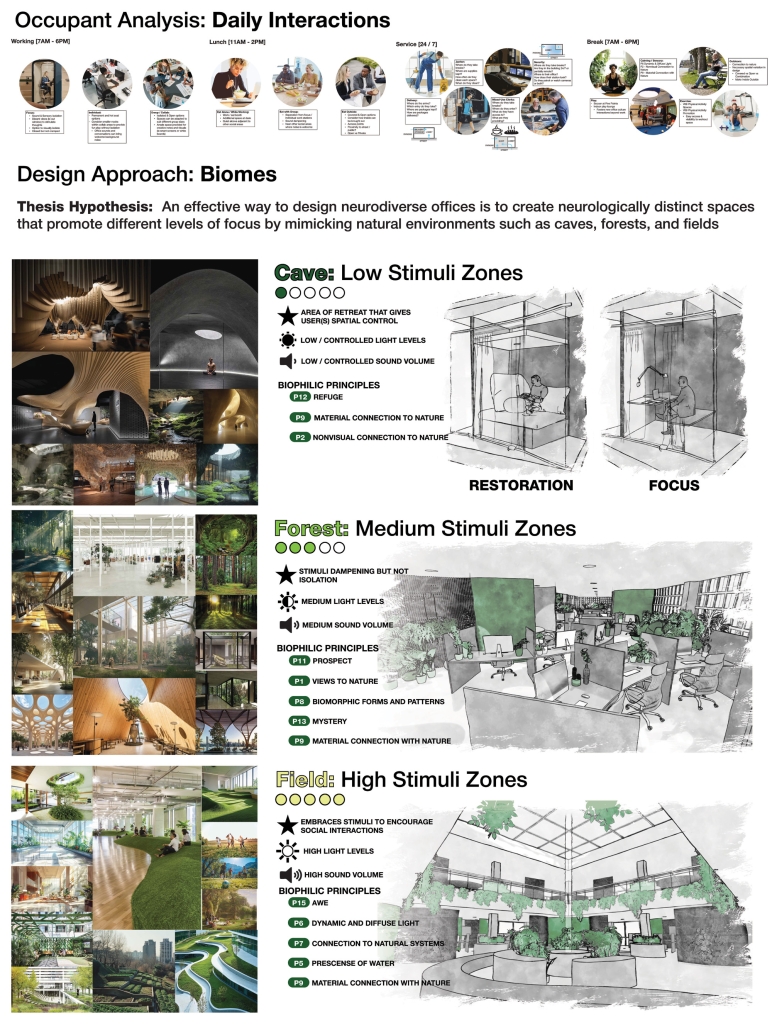

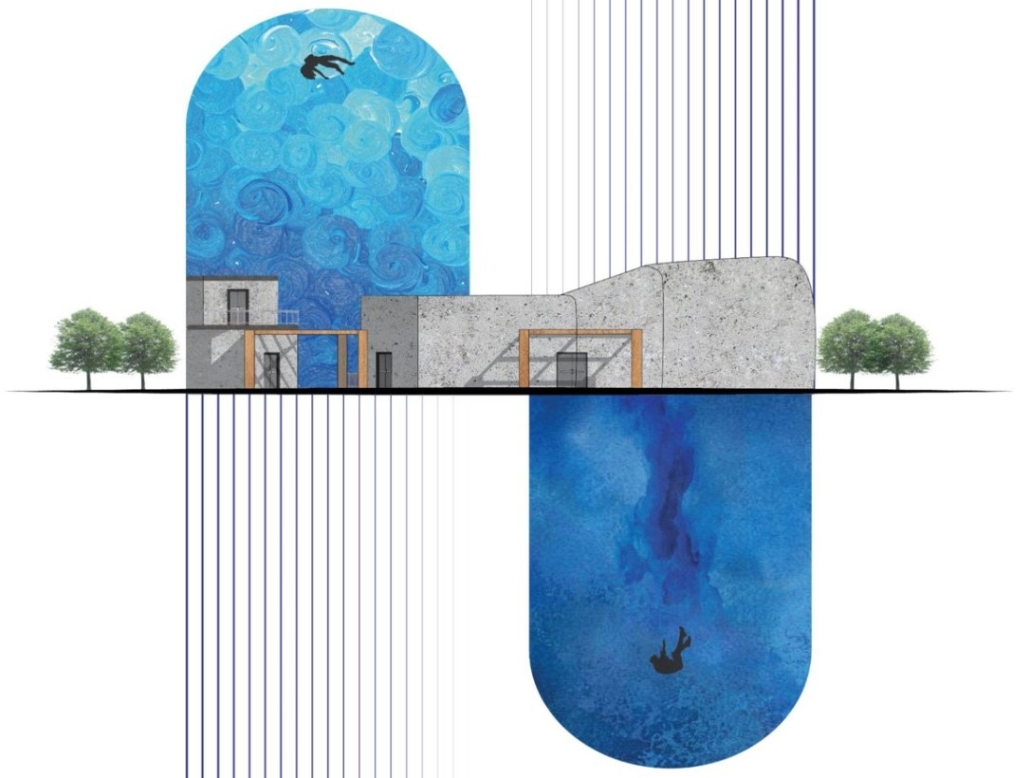

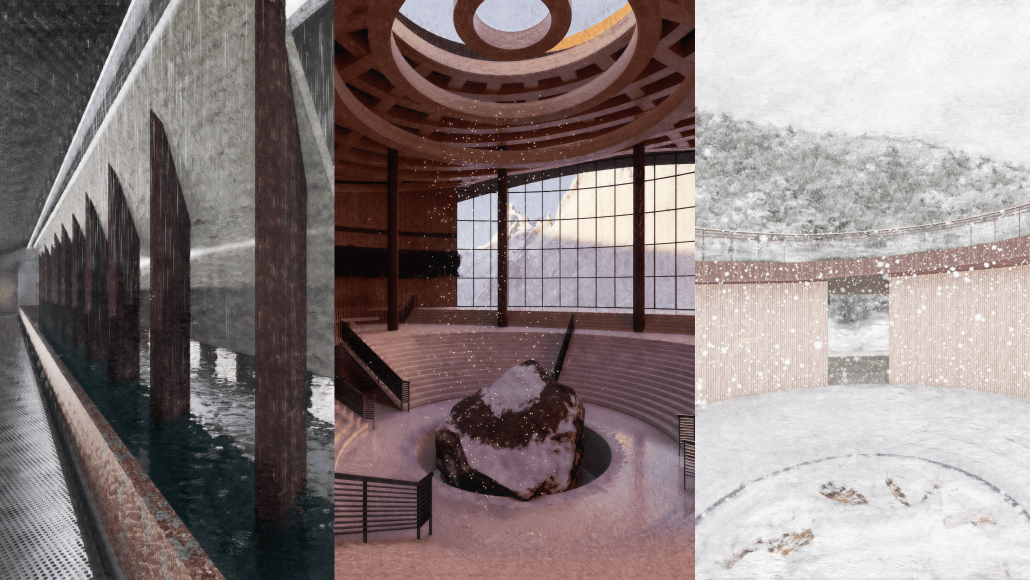

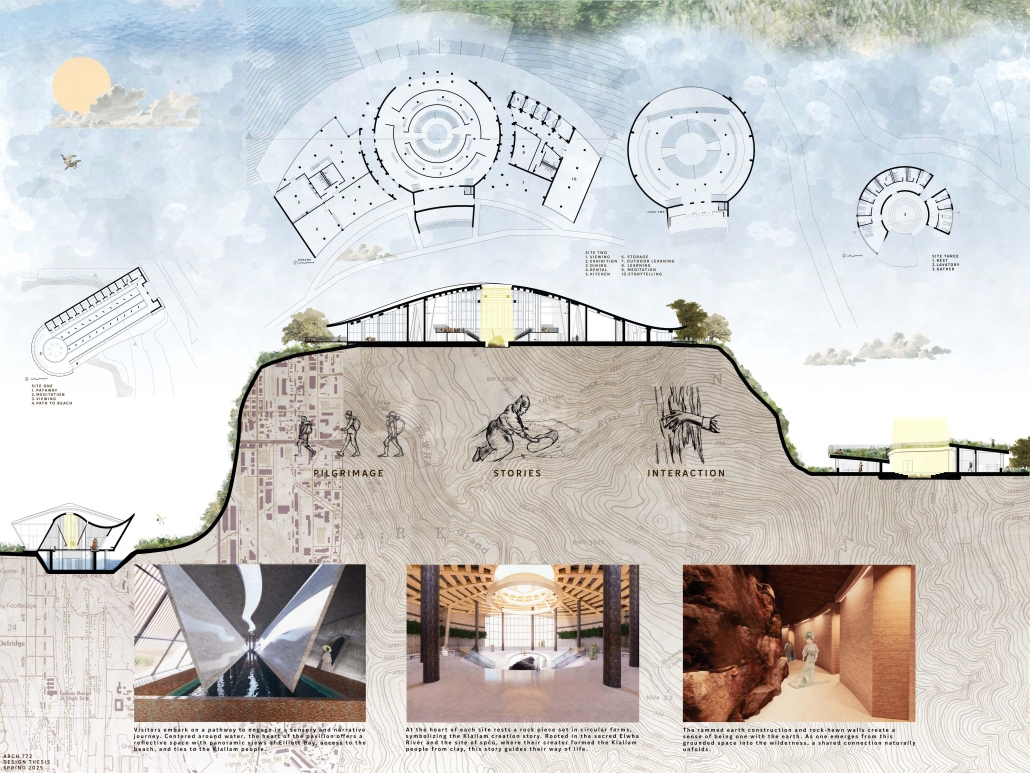

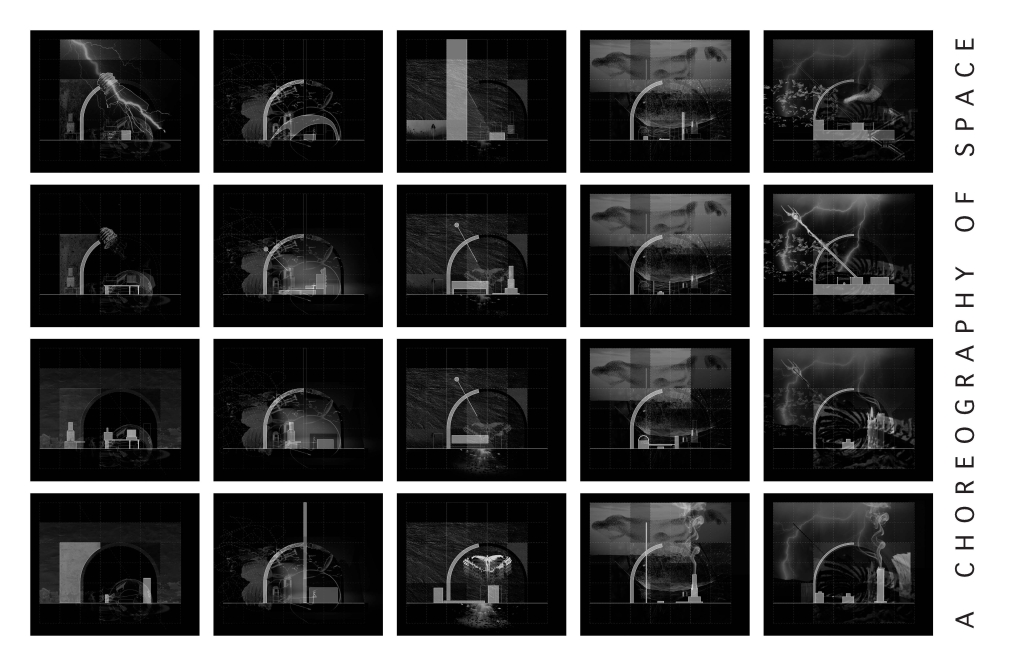

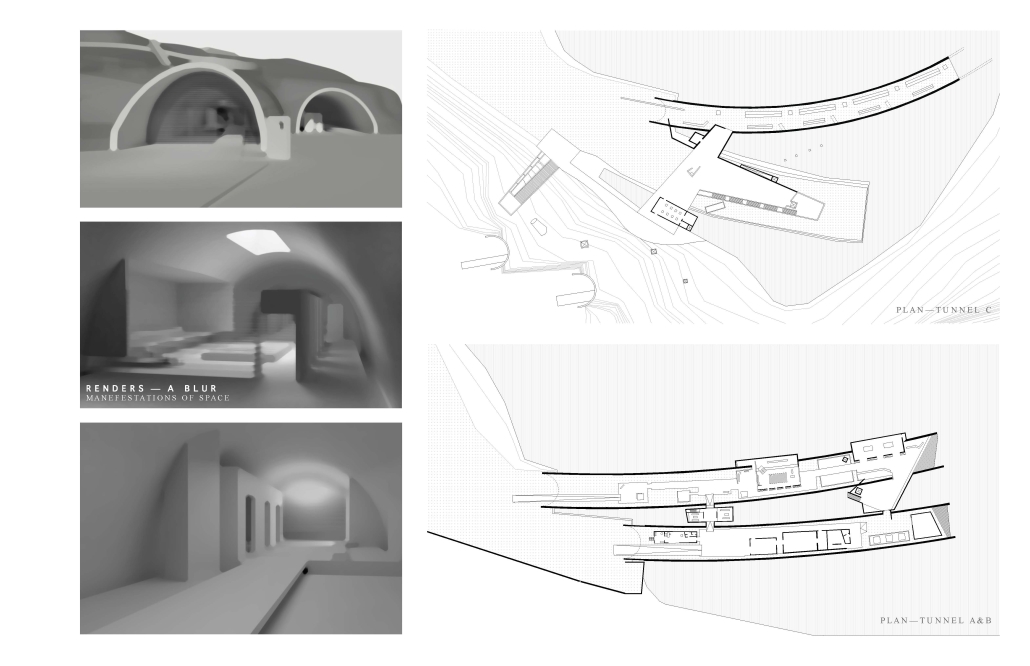

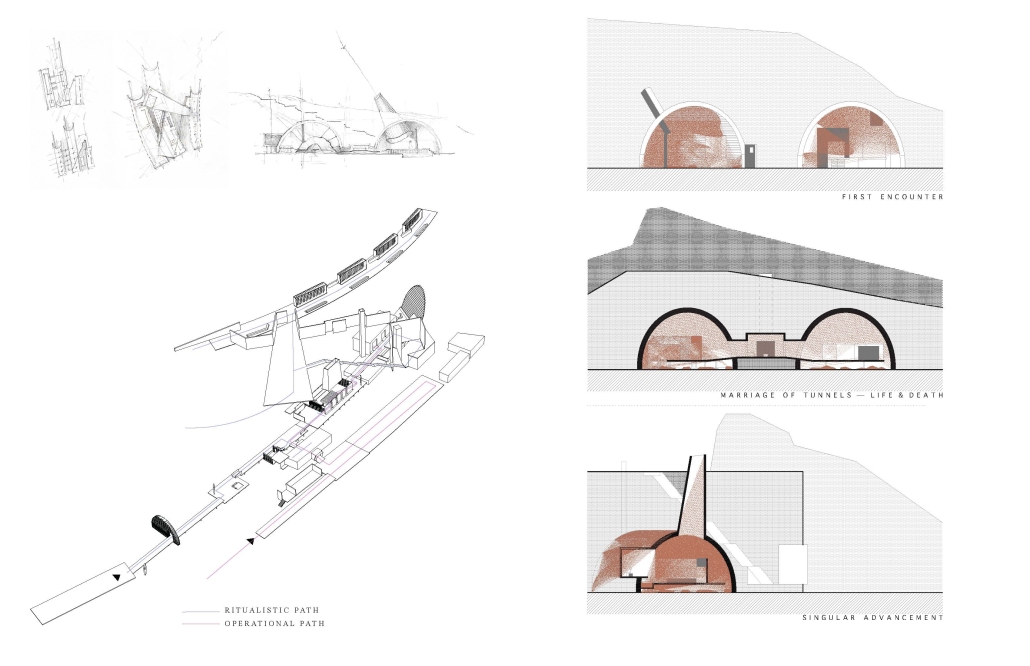

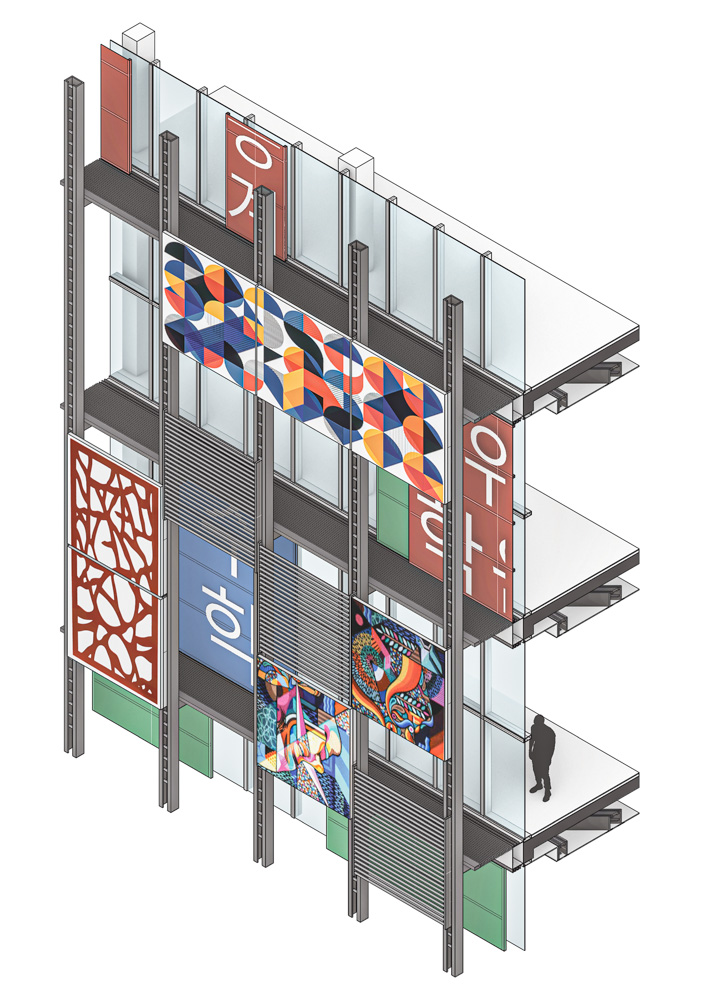

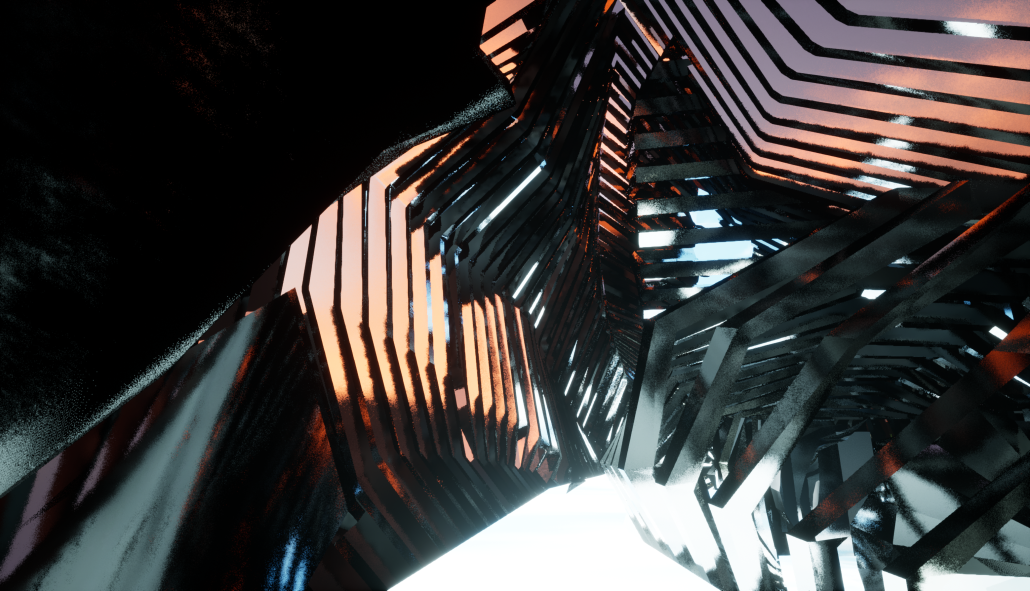

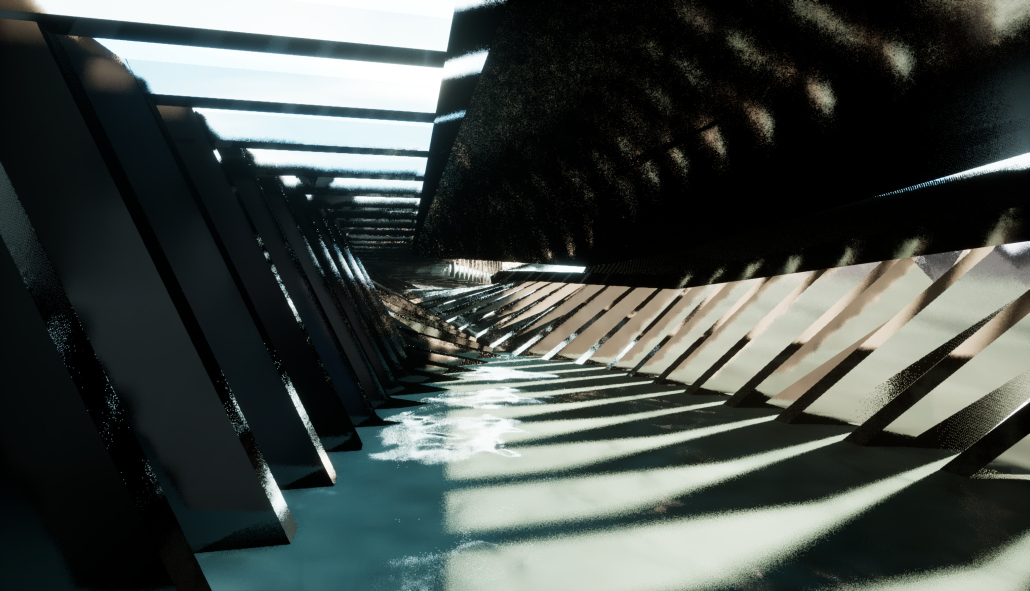

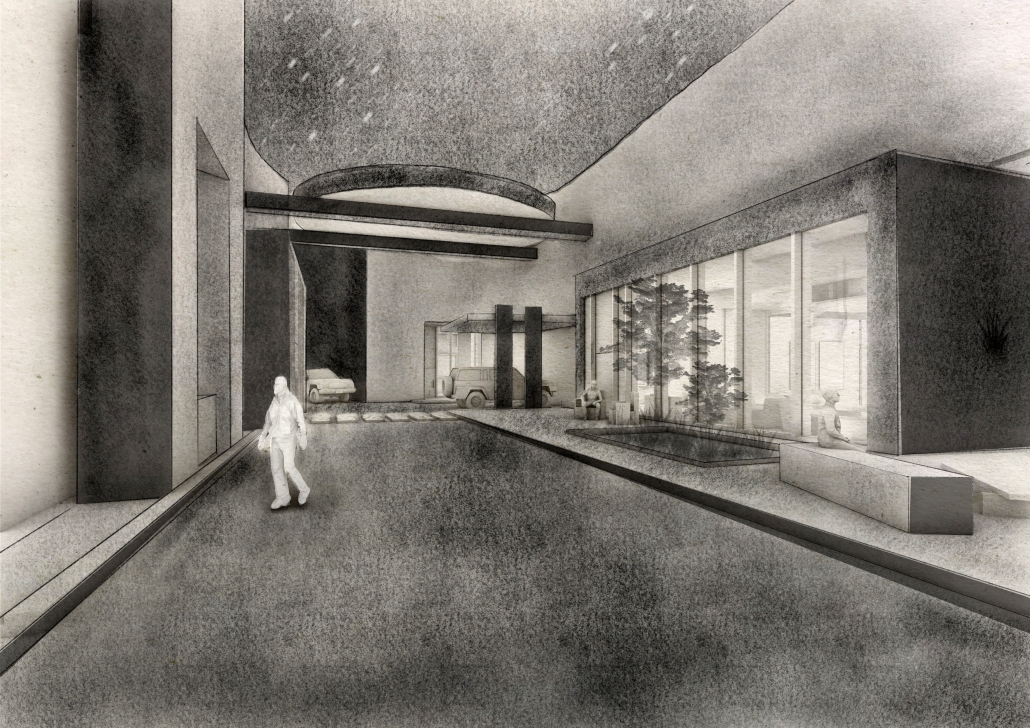

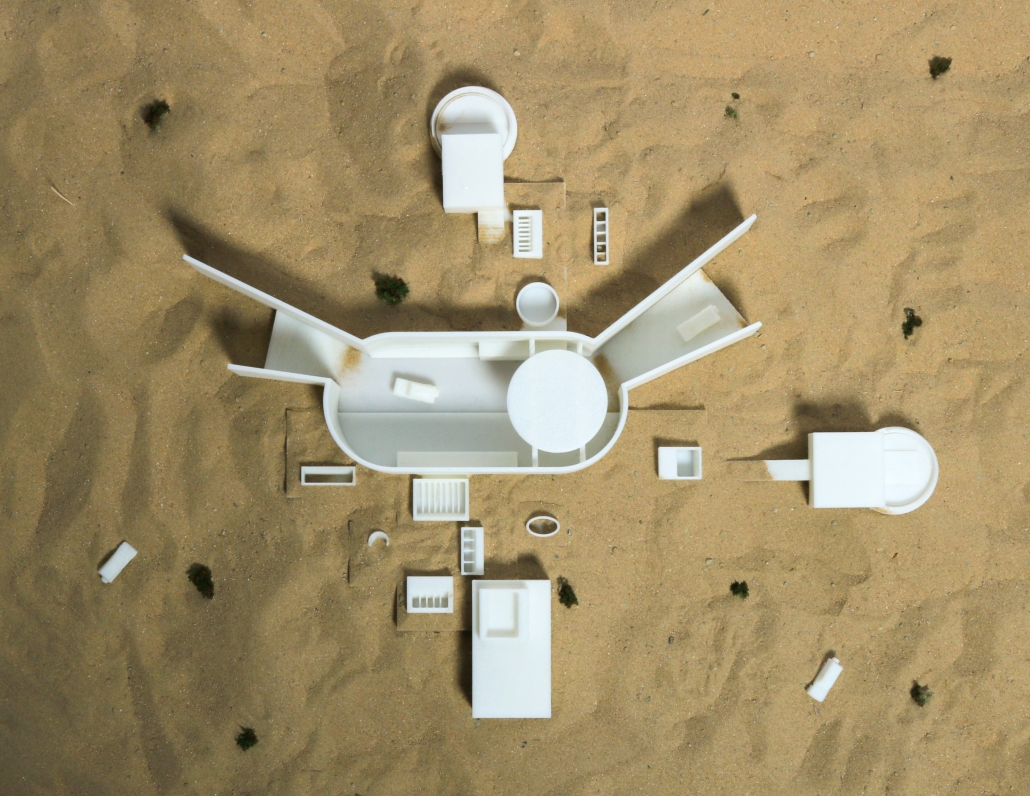

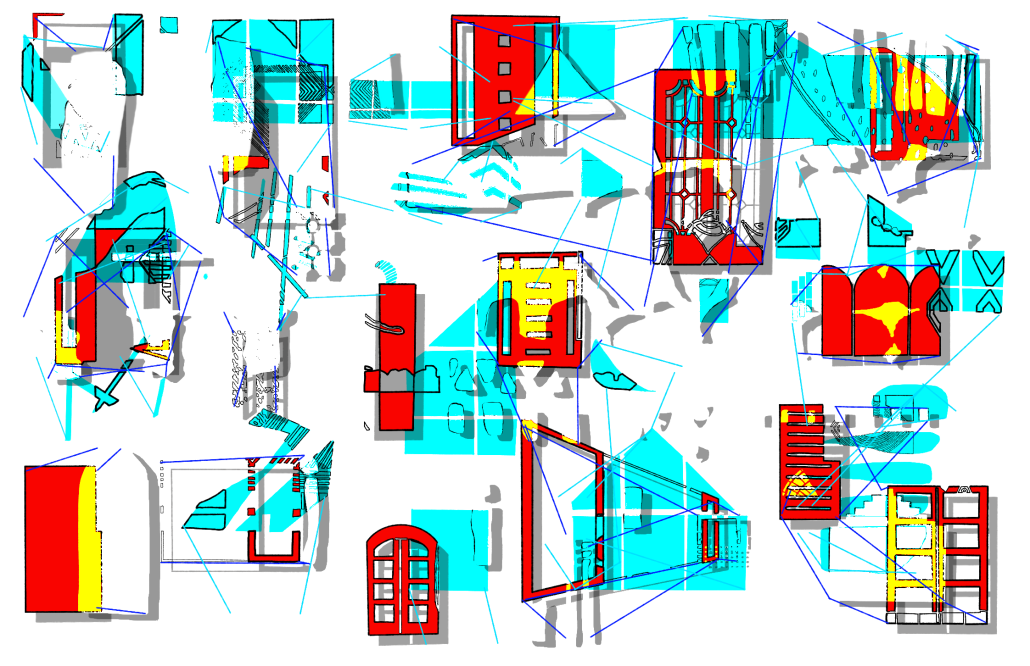

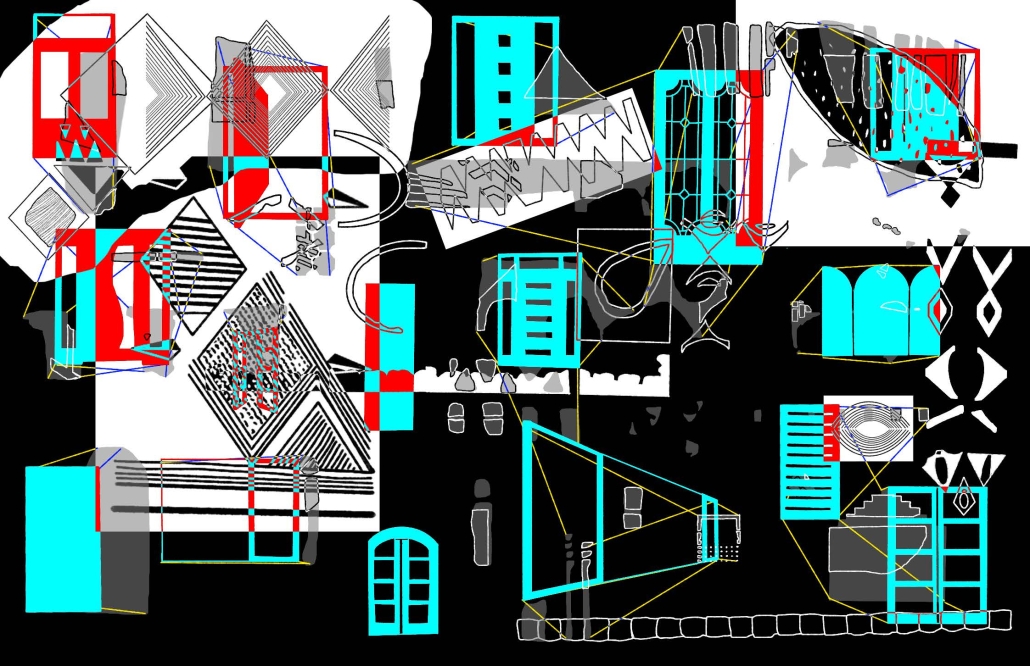

Describe Your Design Style: My design style focuses on the emotionally provocative properties of volume and material, as they contain the incredible ability to encourage patrons to cognitively engage with their surroundings. Influence over the built environment carries an innate responsibility of care for the human experience, and I believe positively affecting users’ emotions and encouraging them to actively take part in the world around them strengthens communities and enhances local culture.

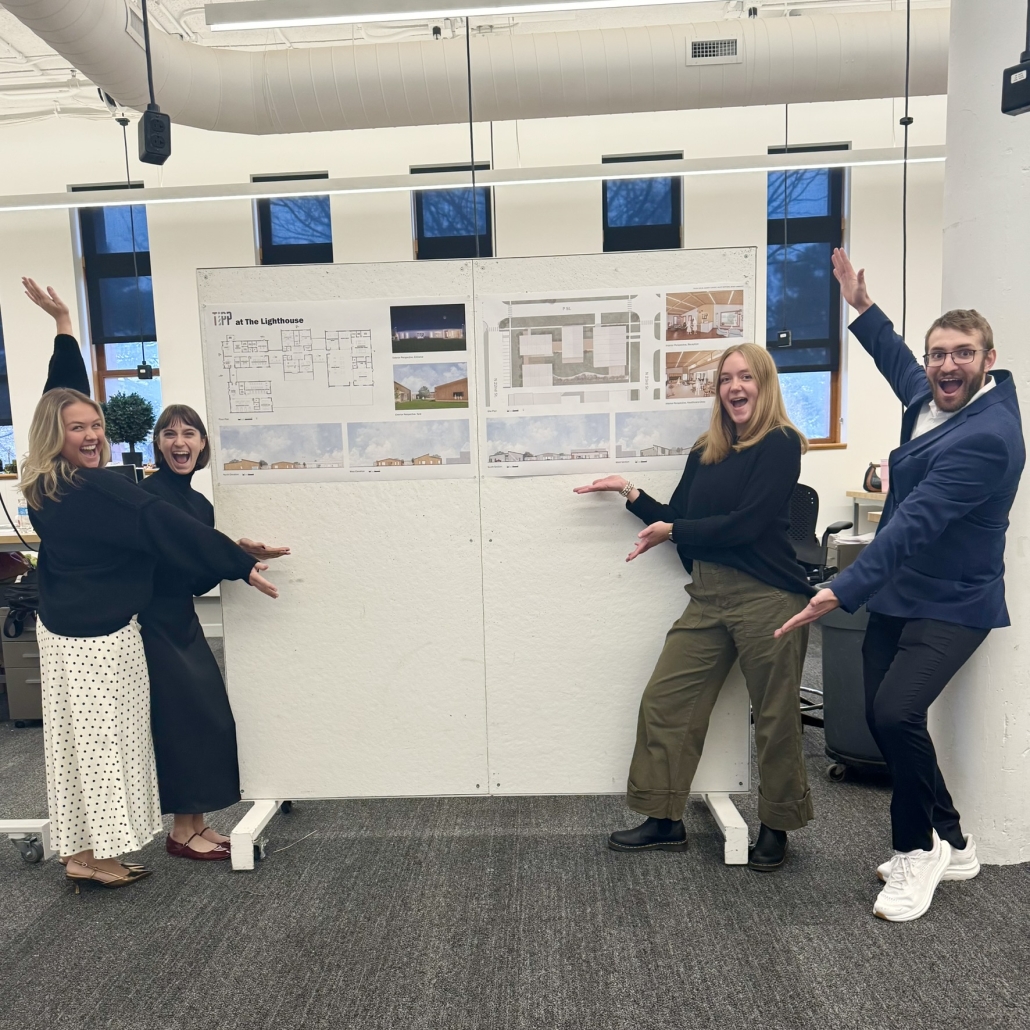

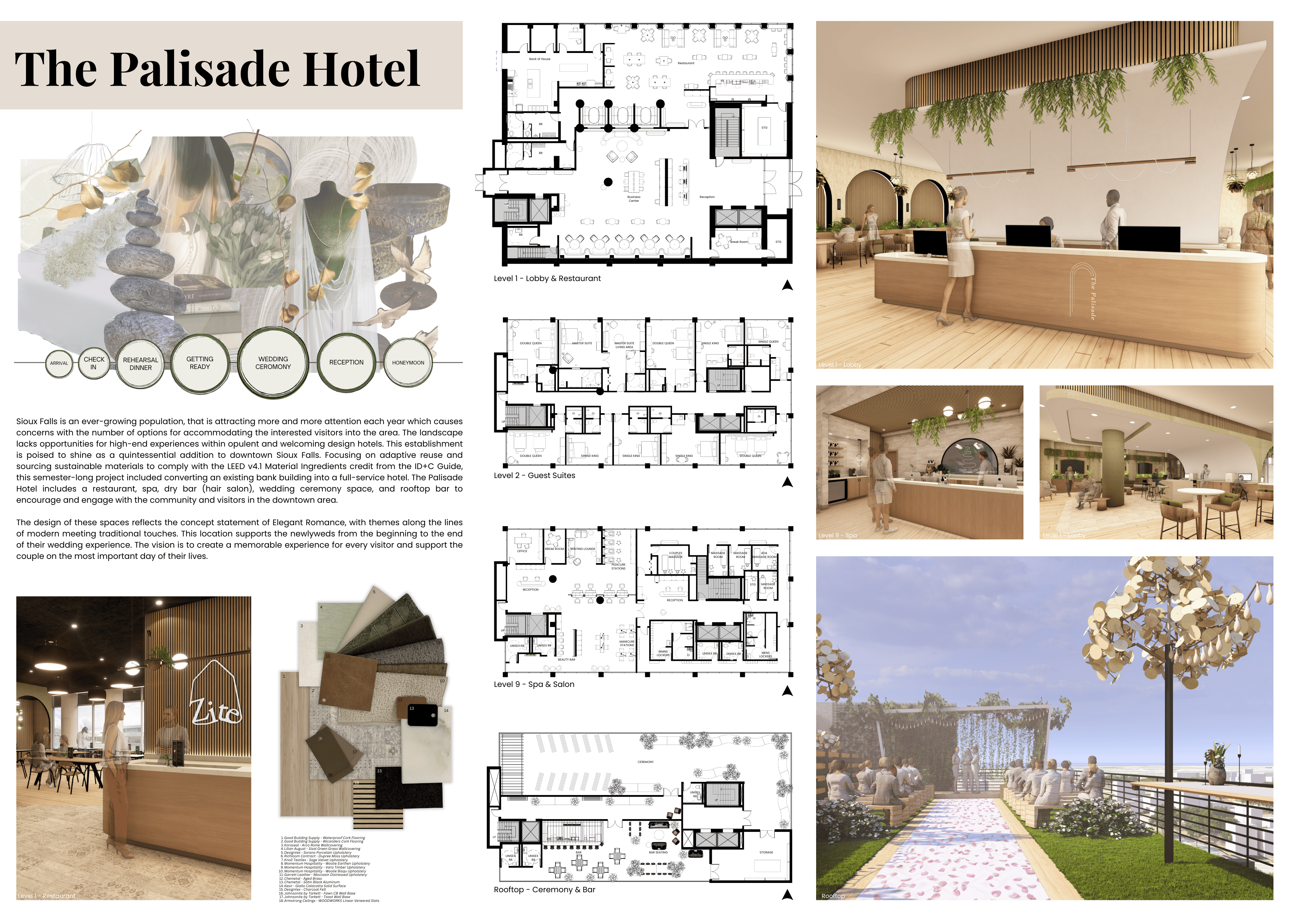

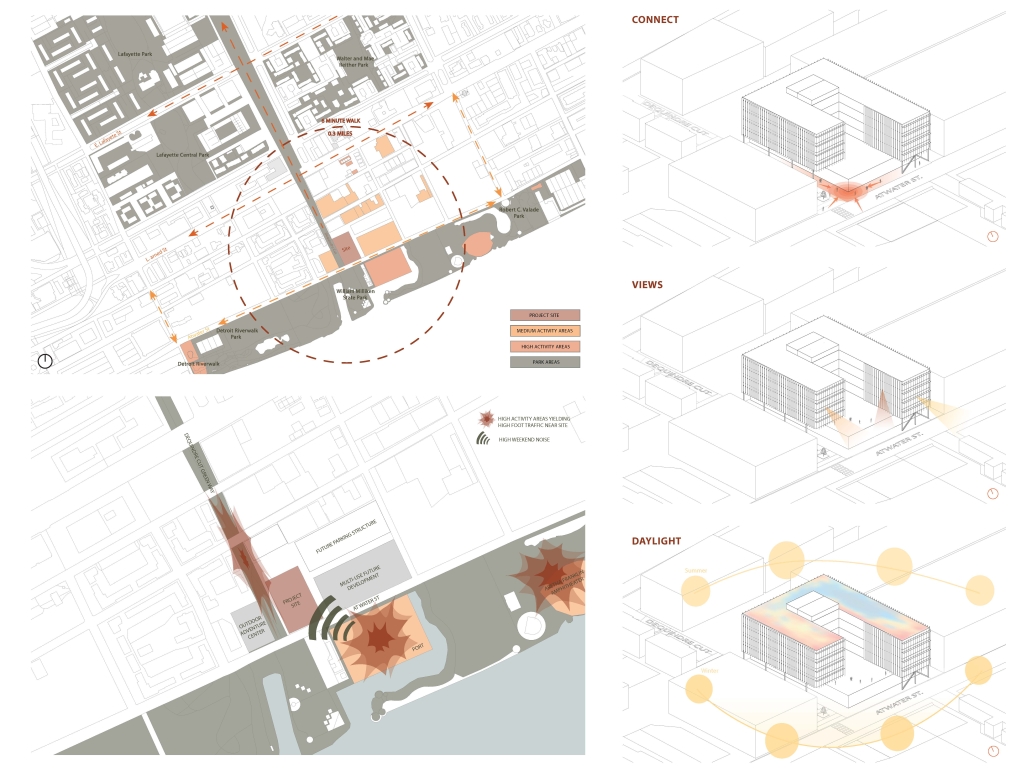

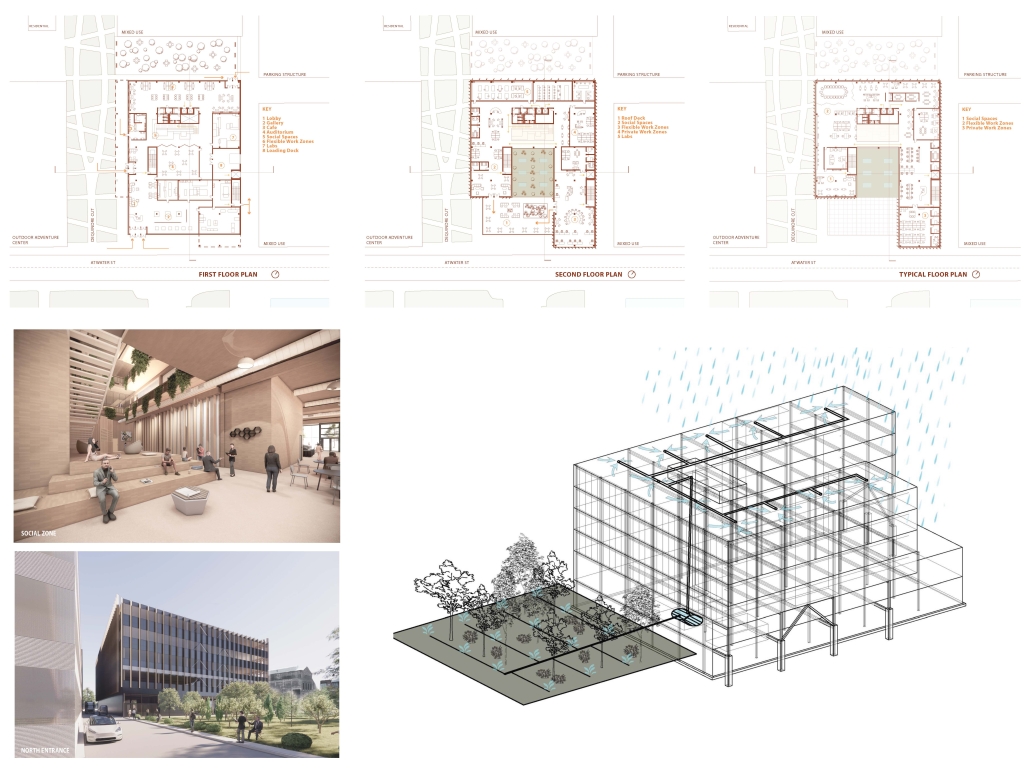

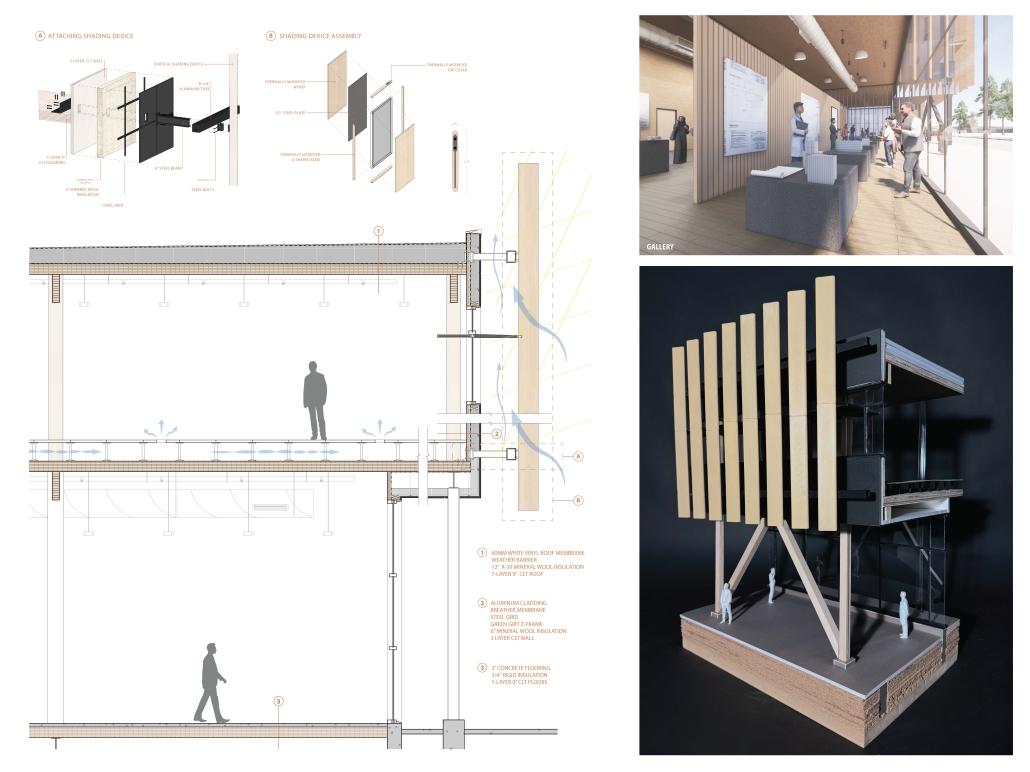

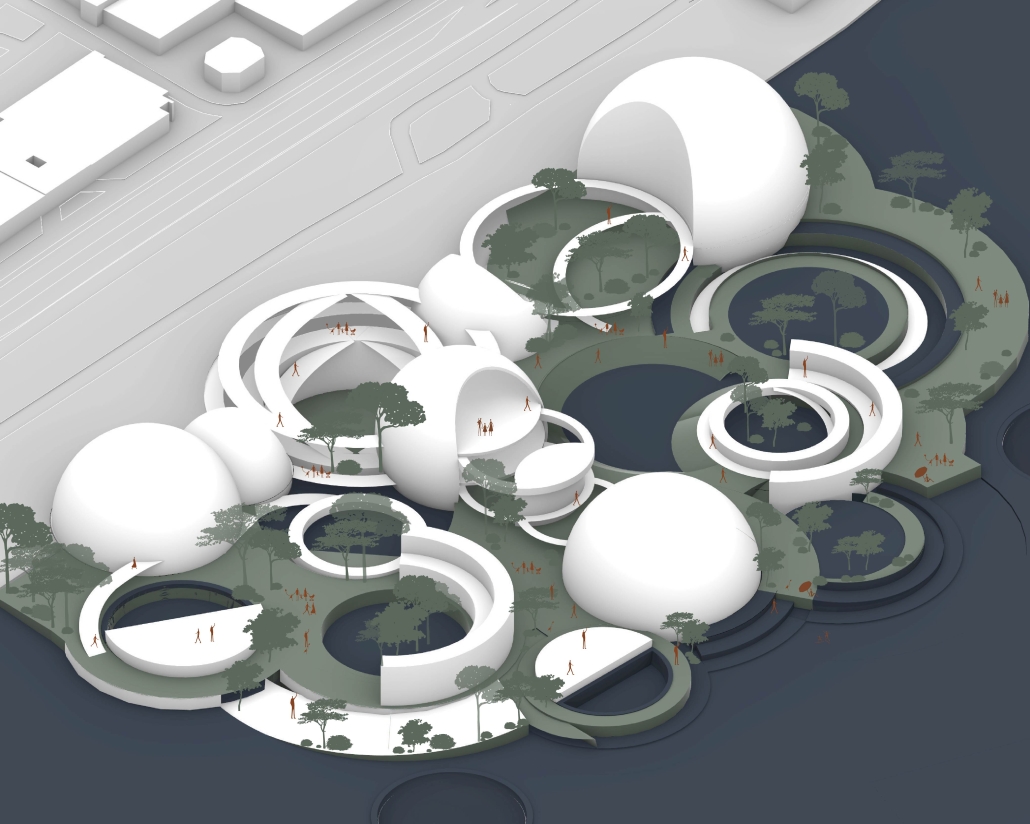

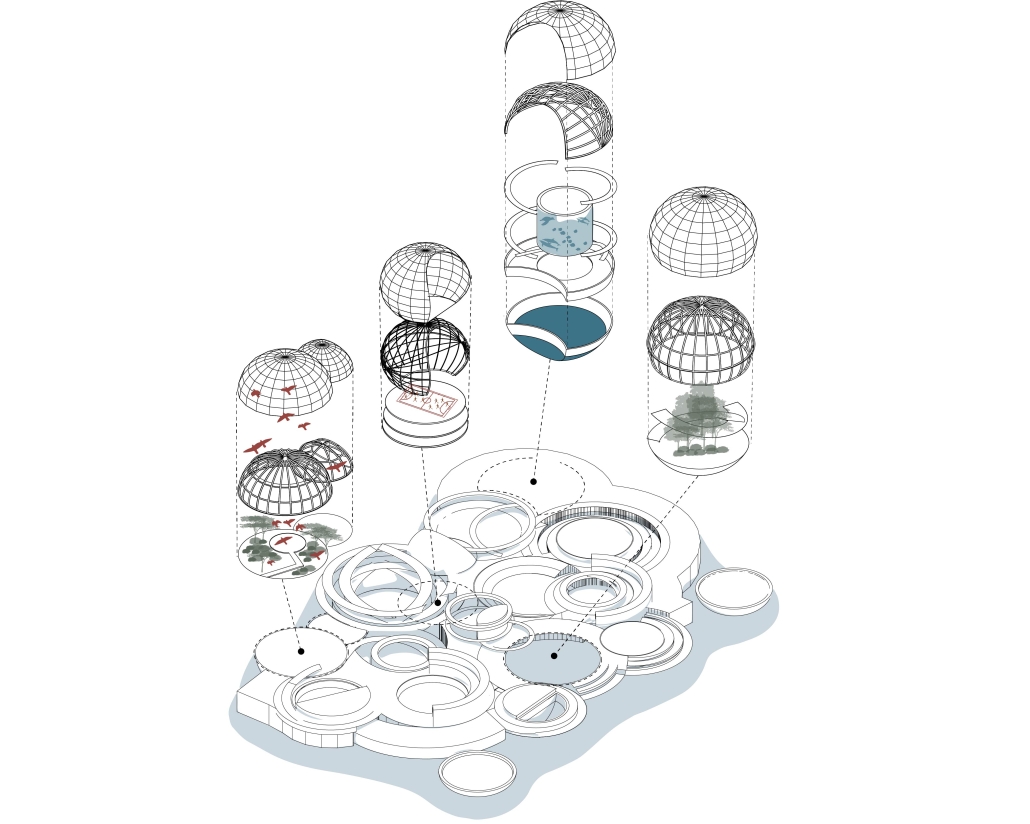

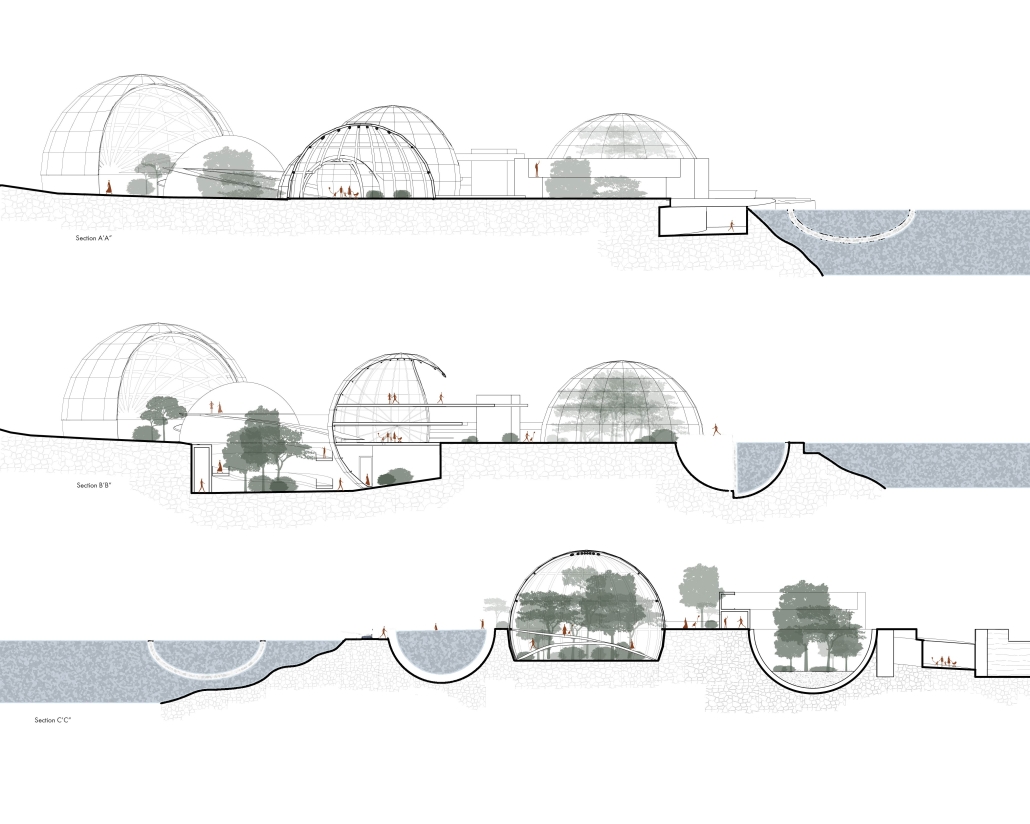

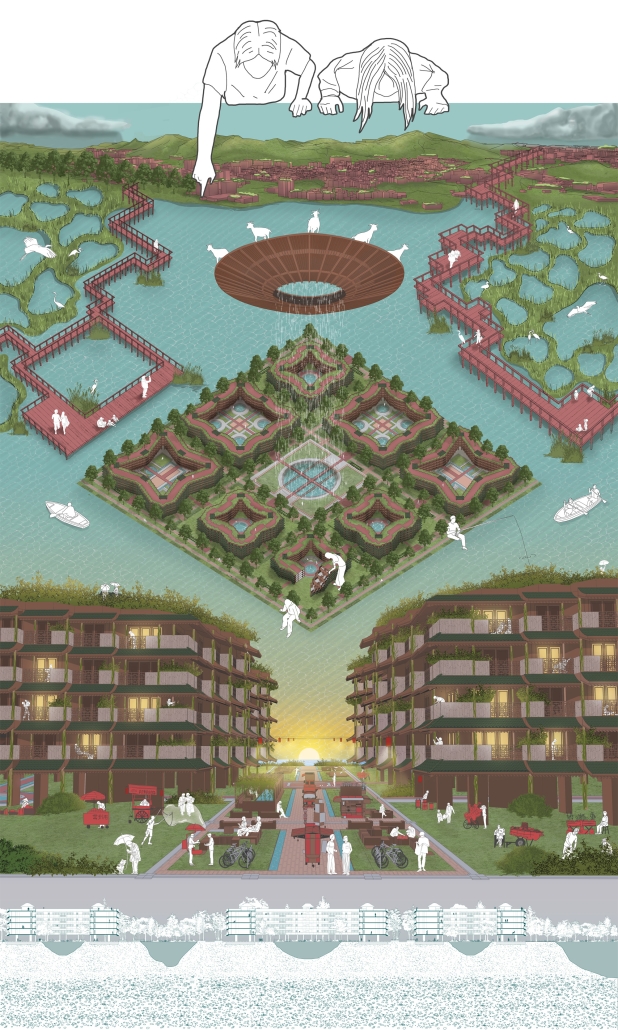

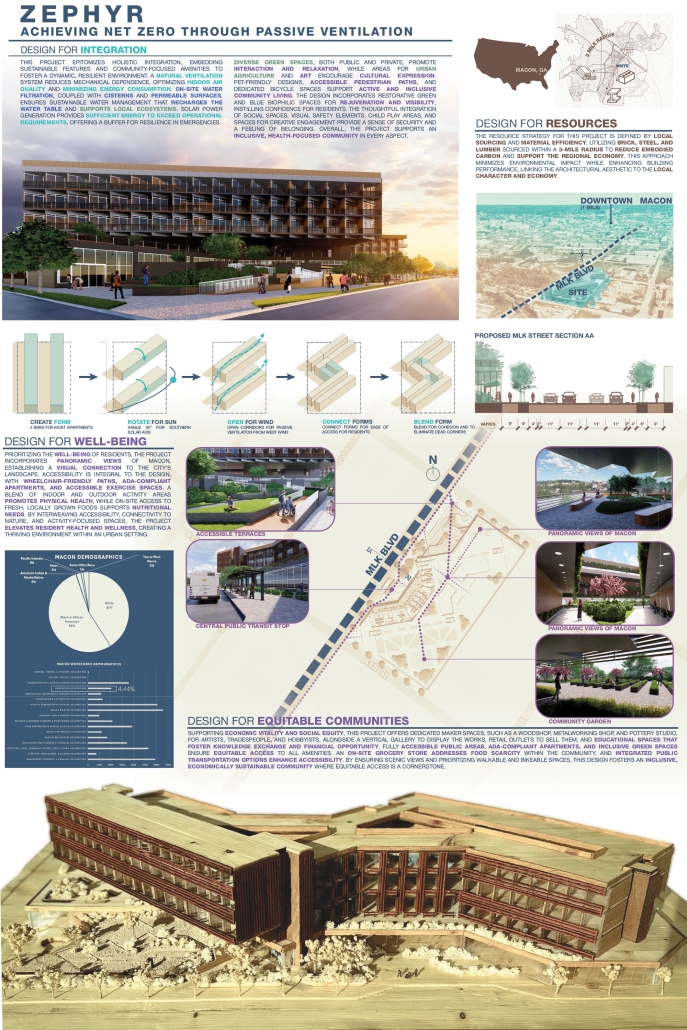

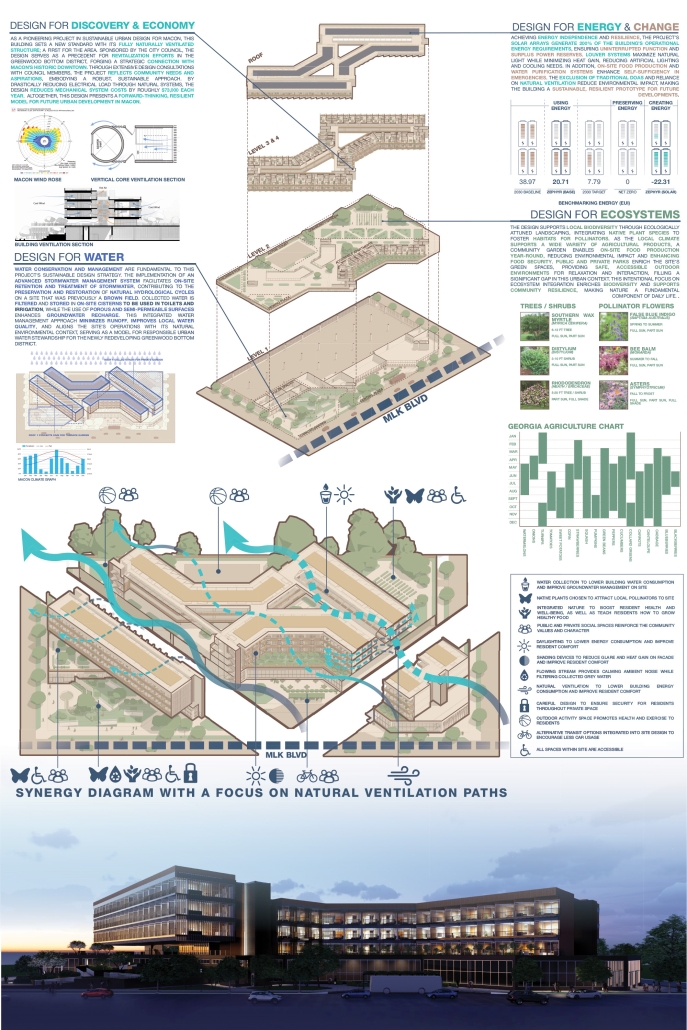

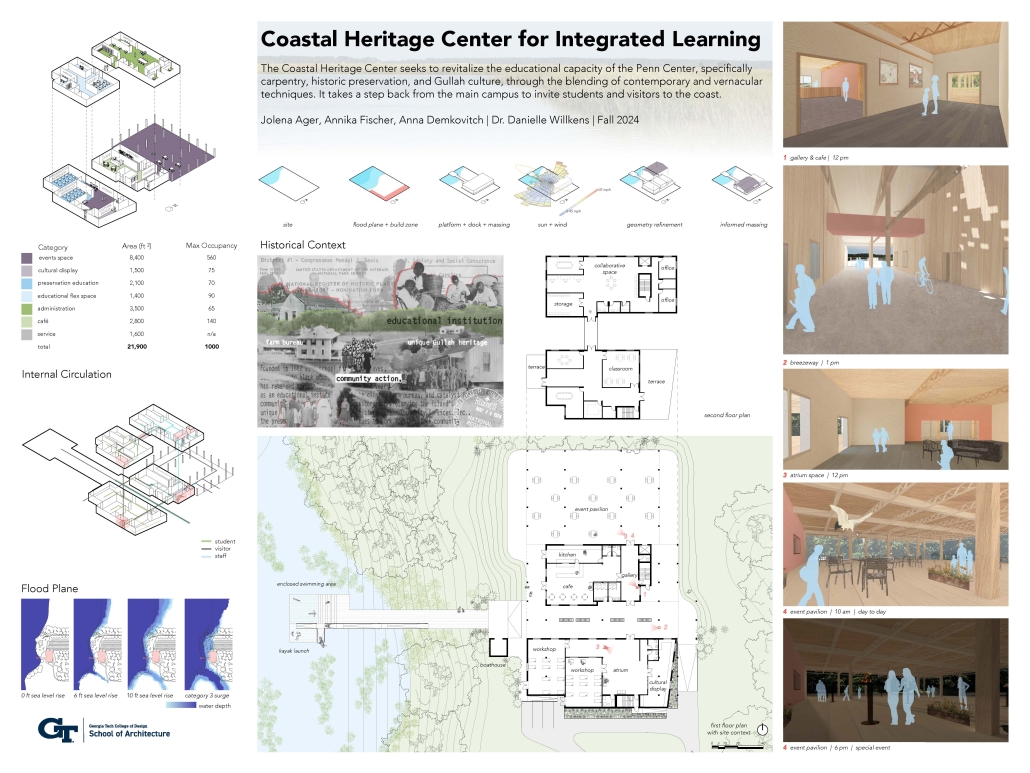

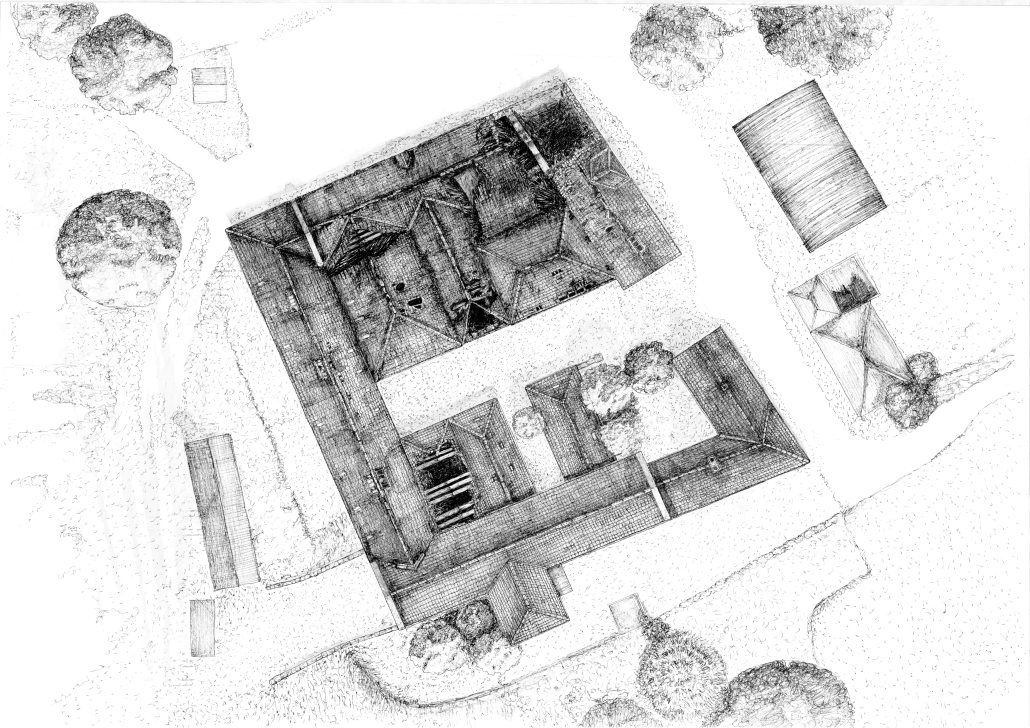

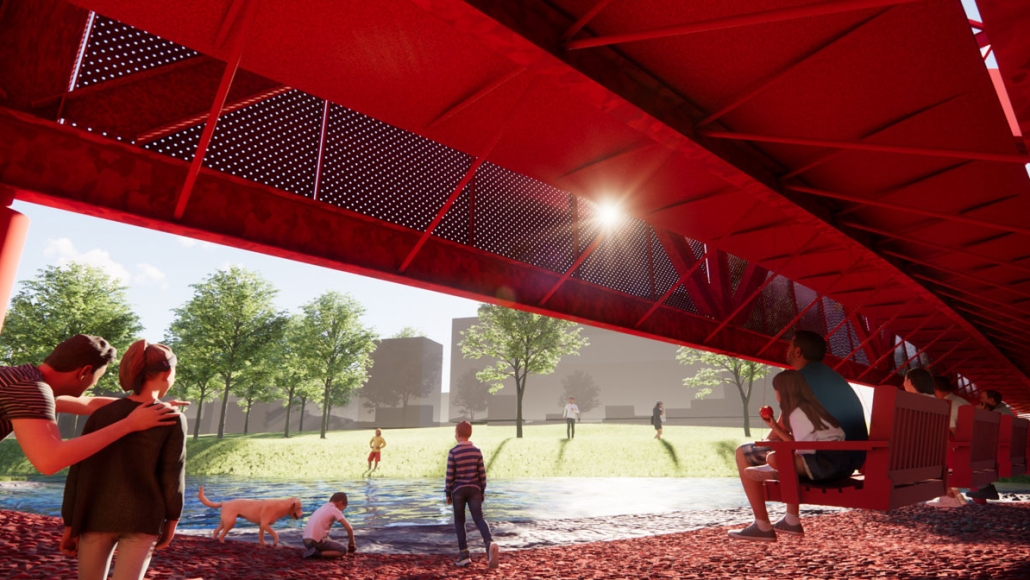

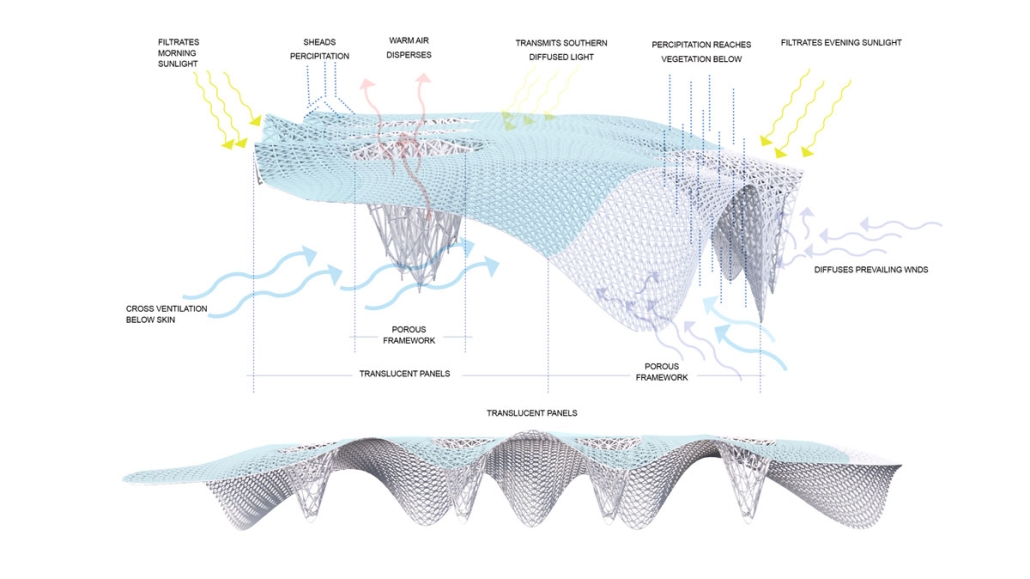

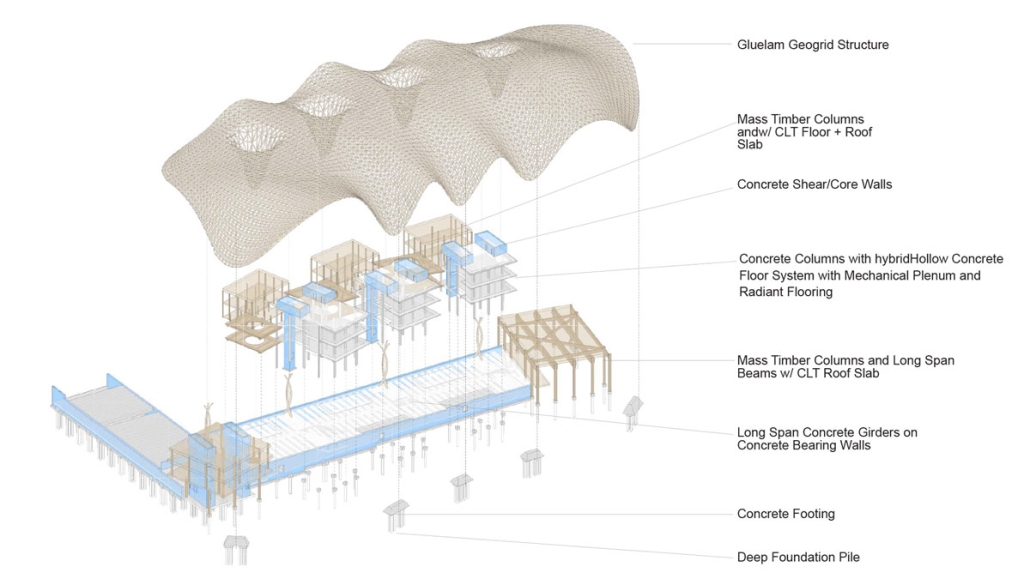

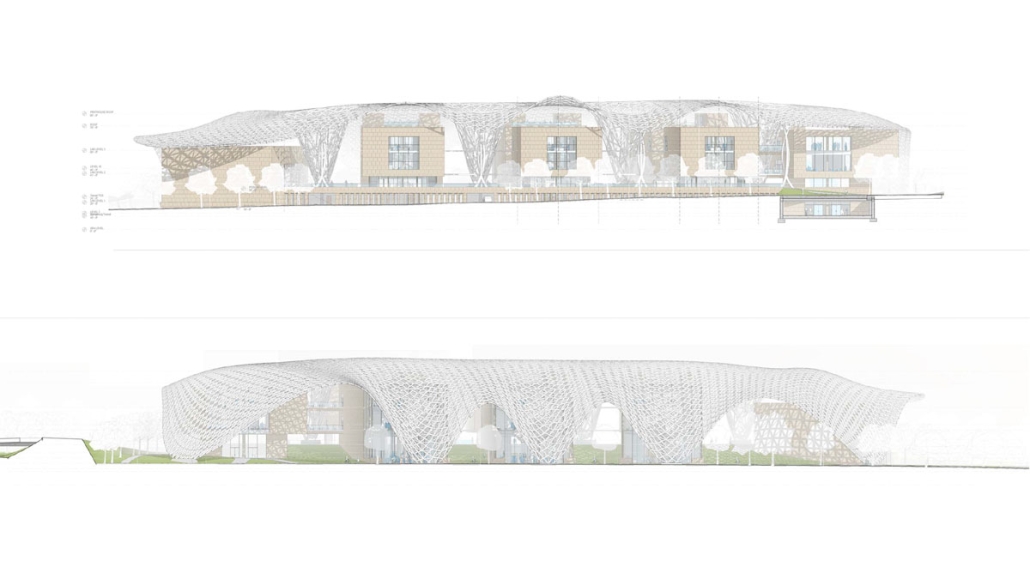

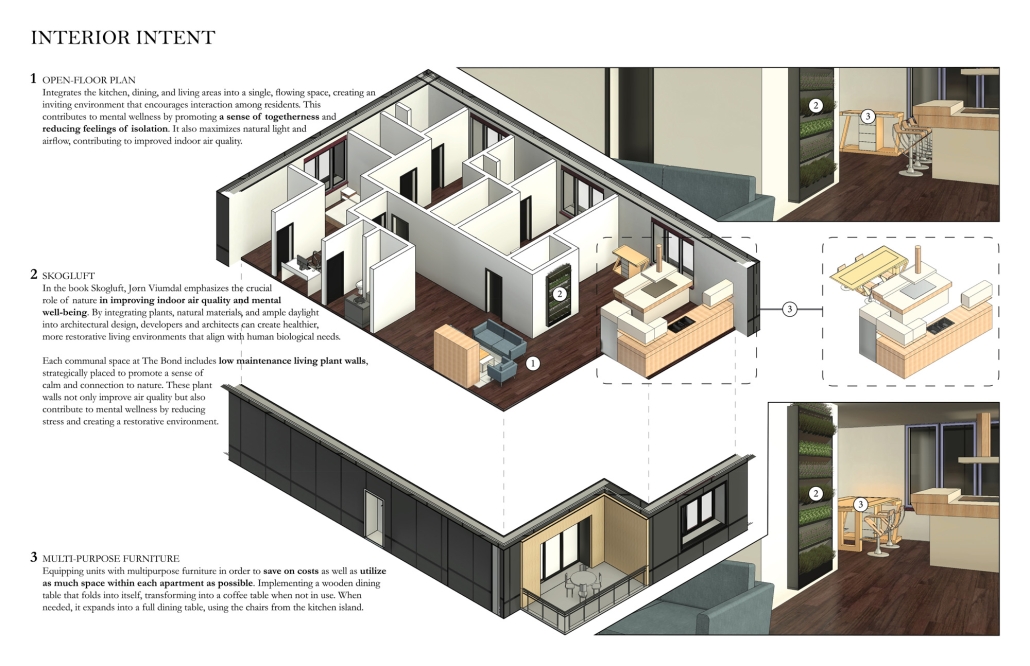

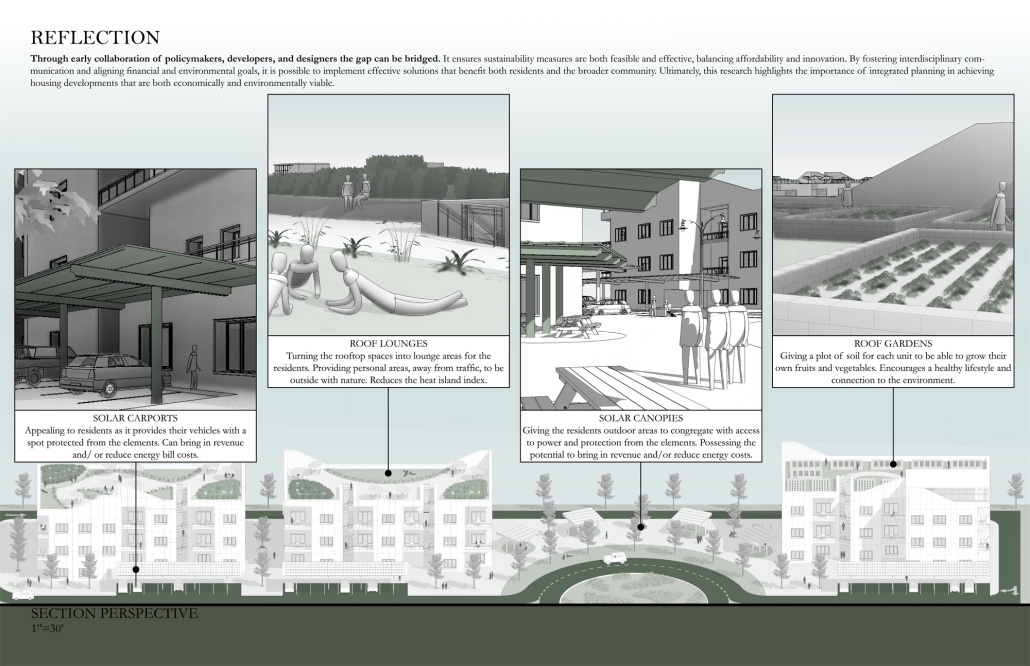

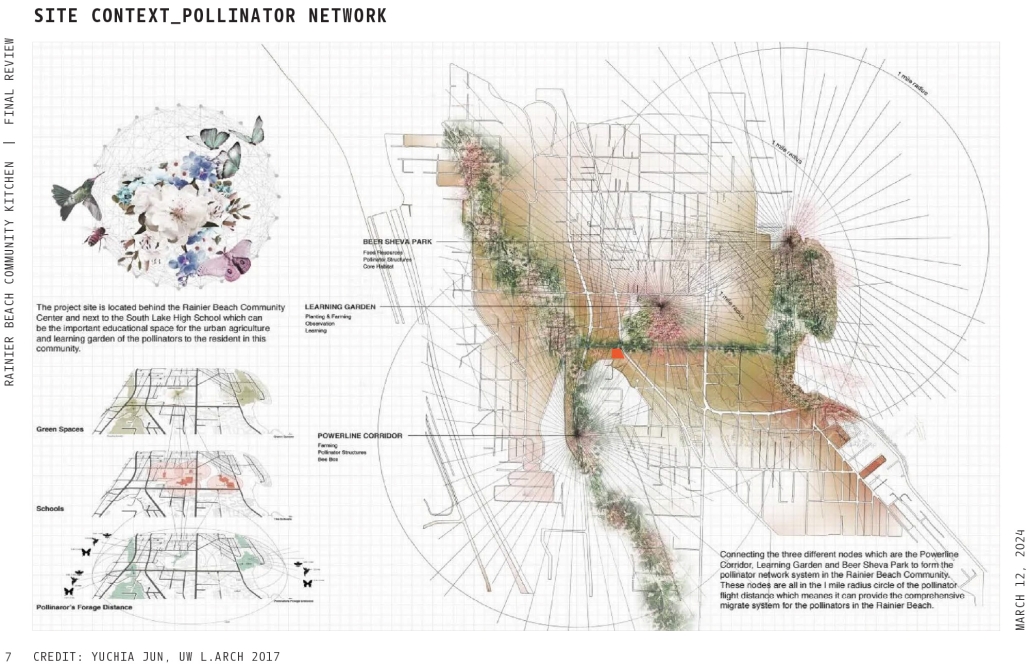

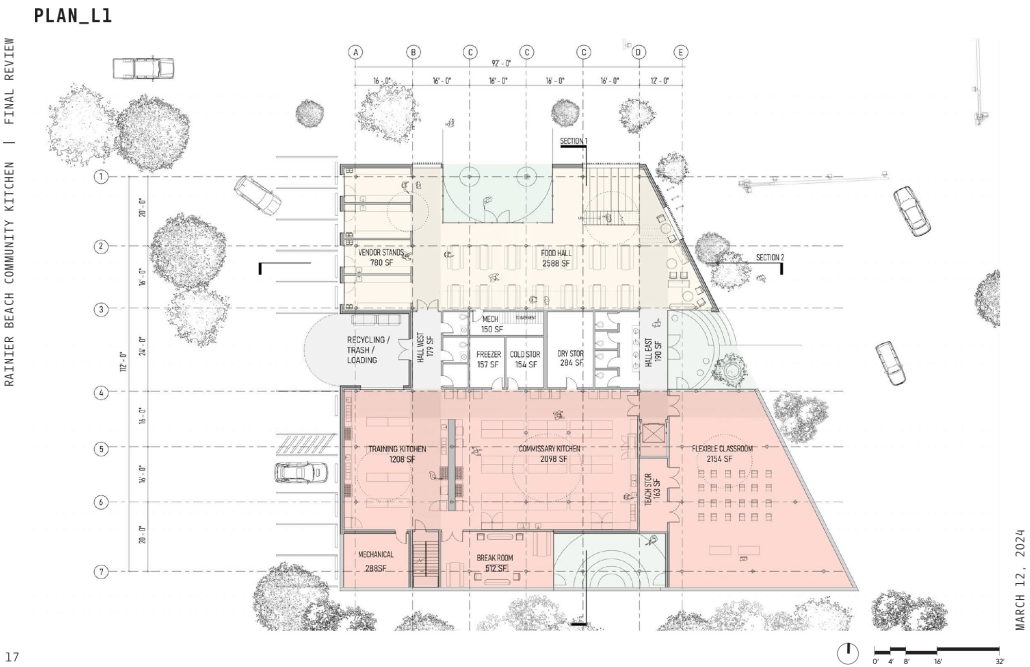

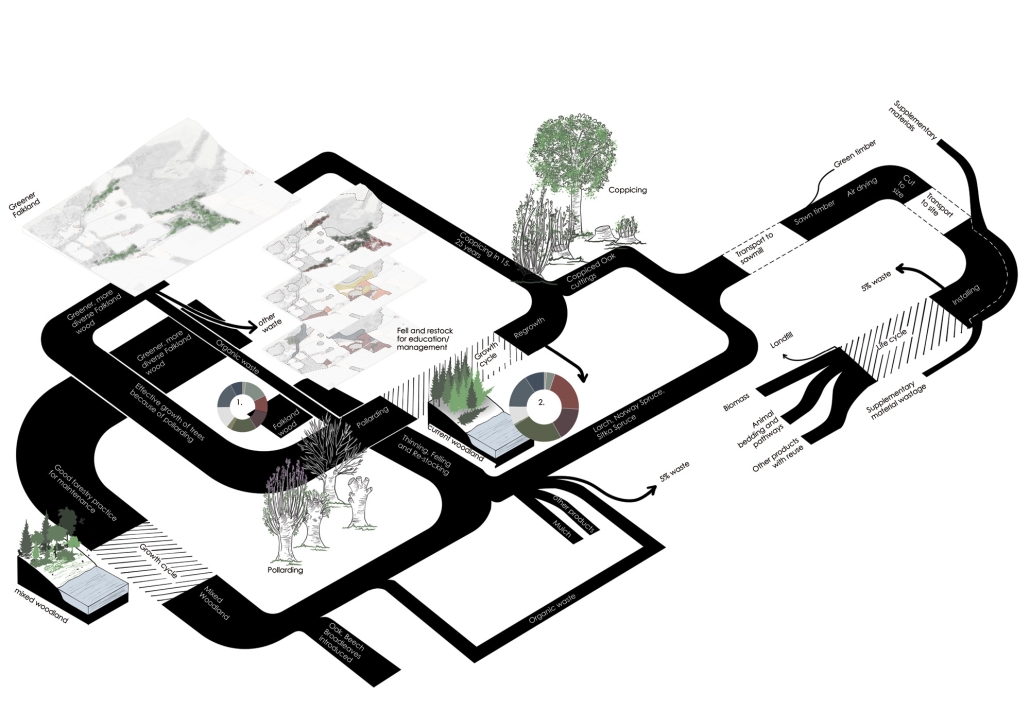

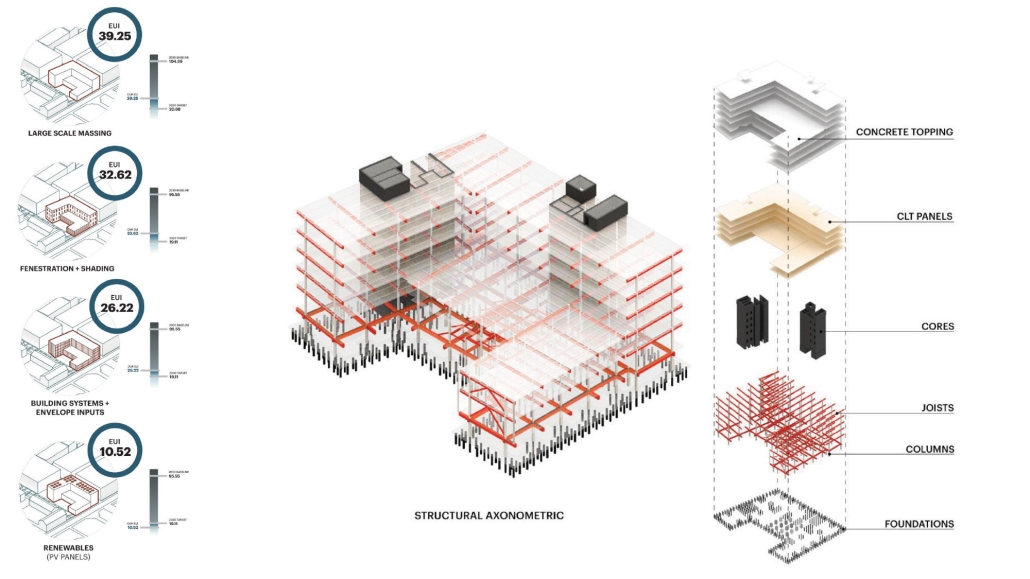

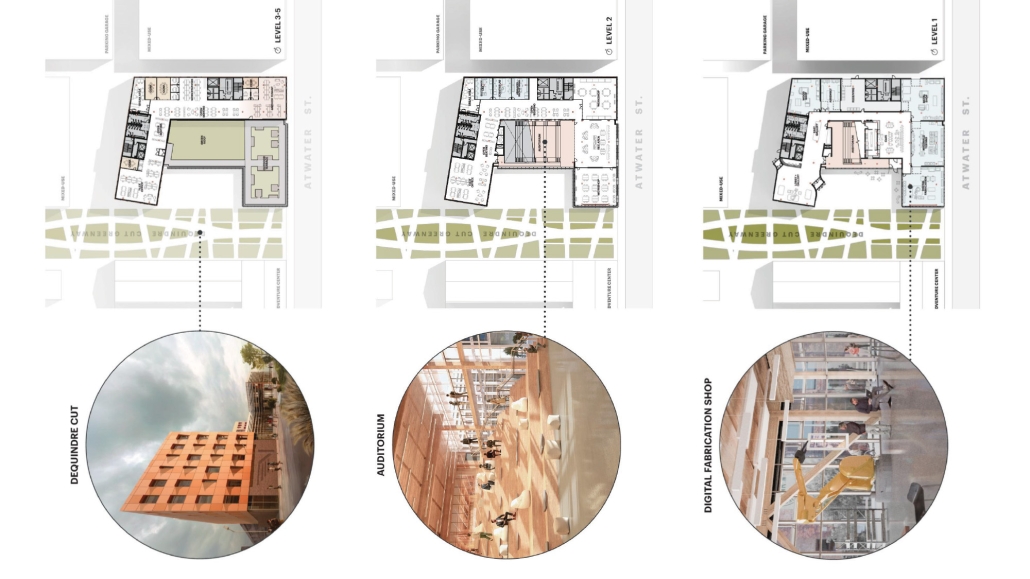

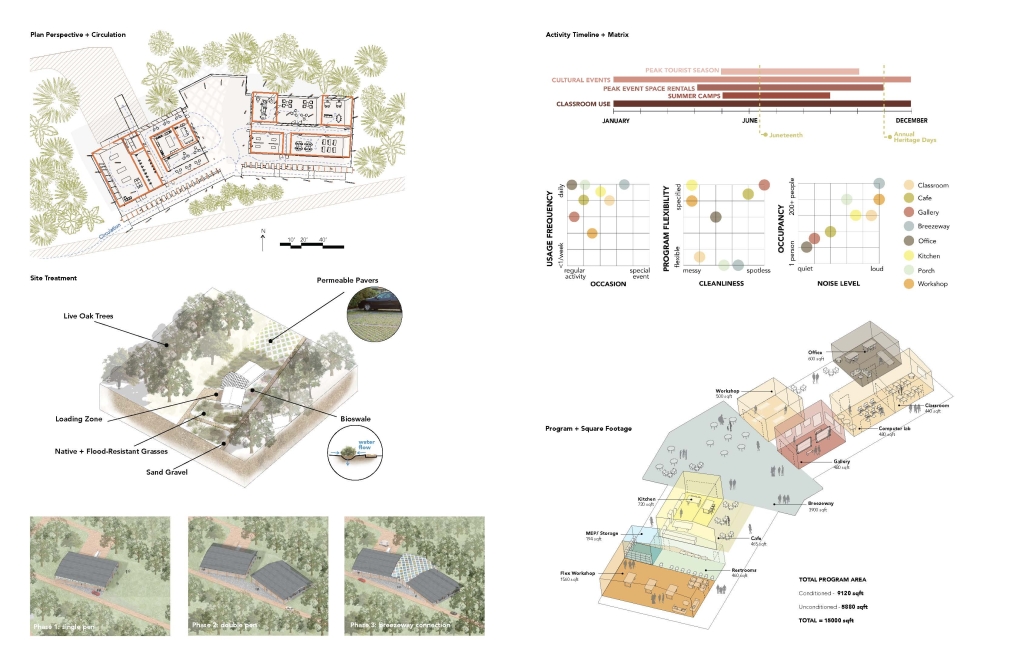

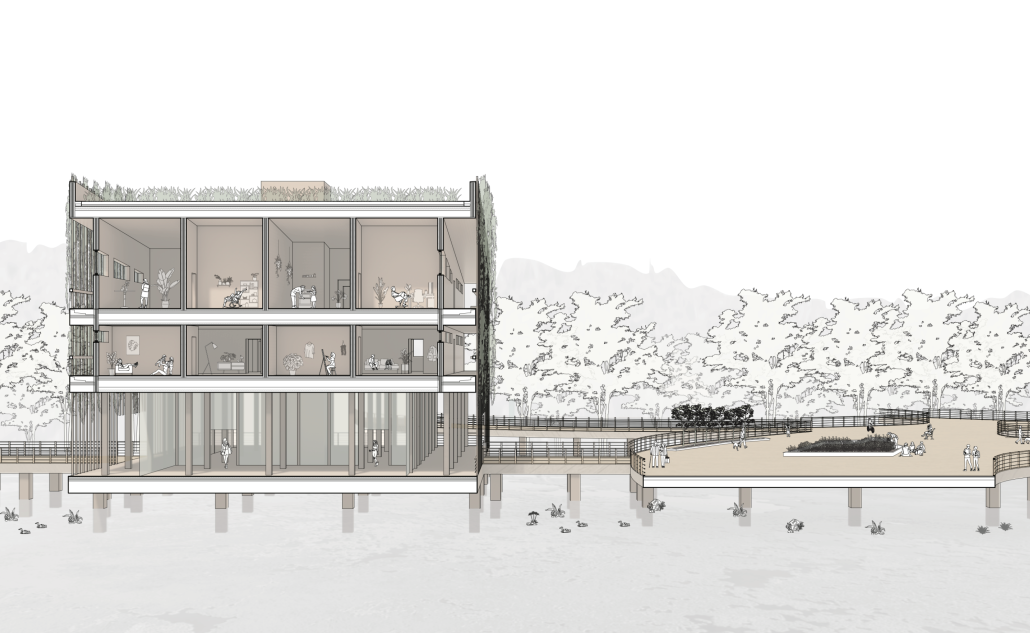

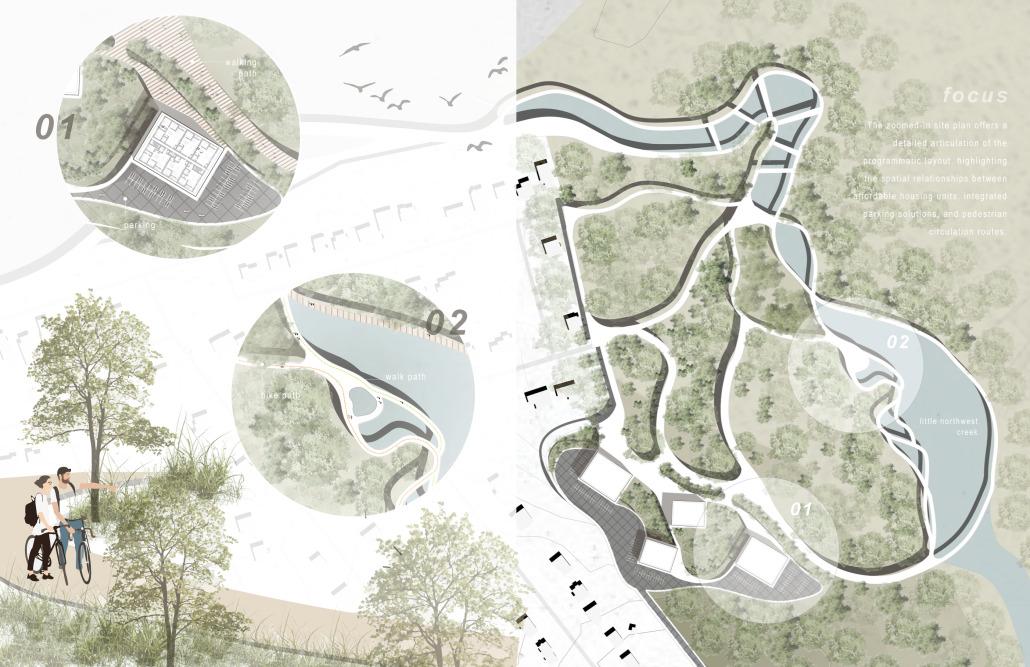

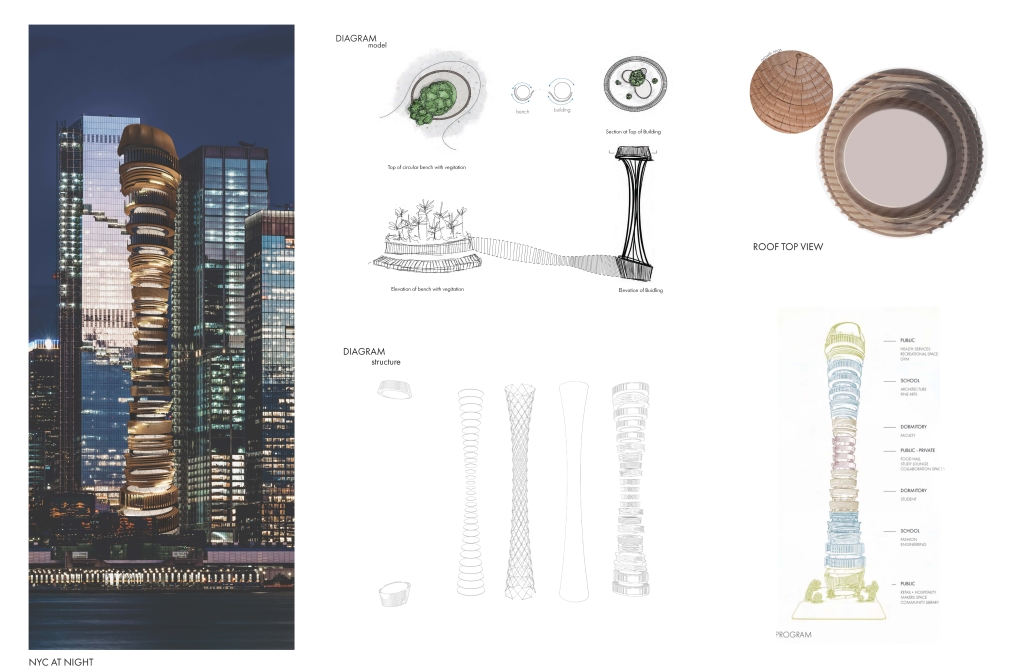

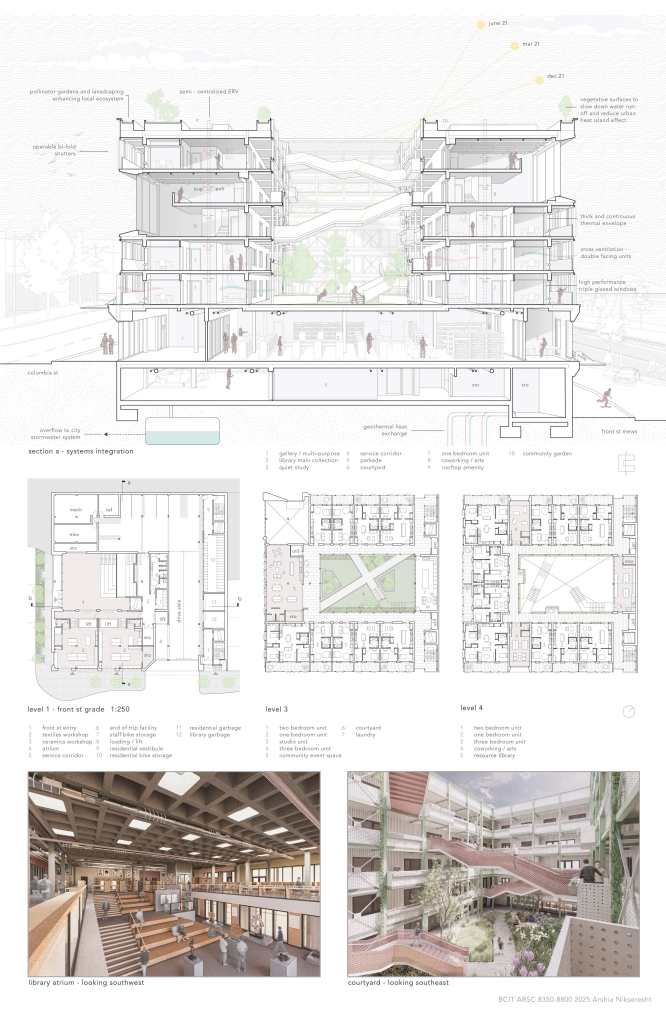

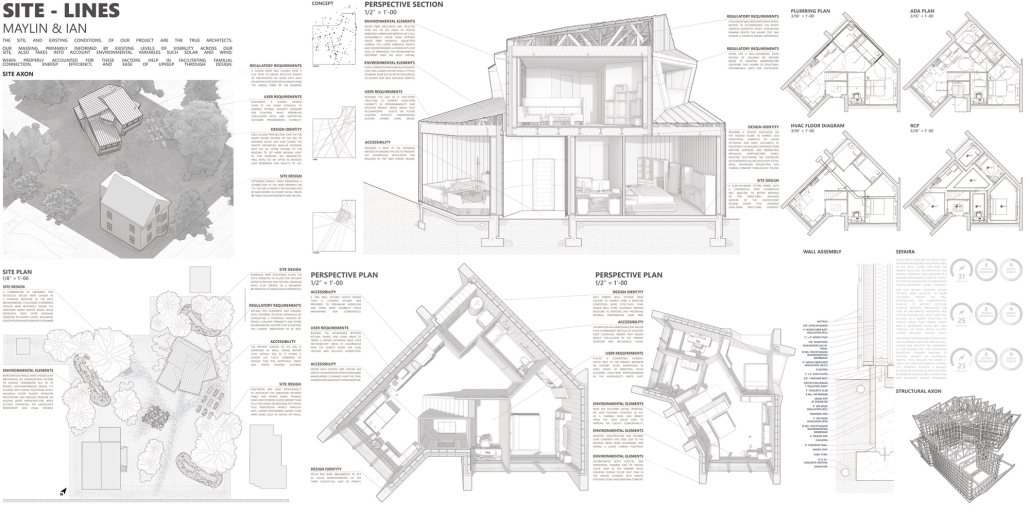

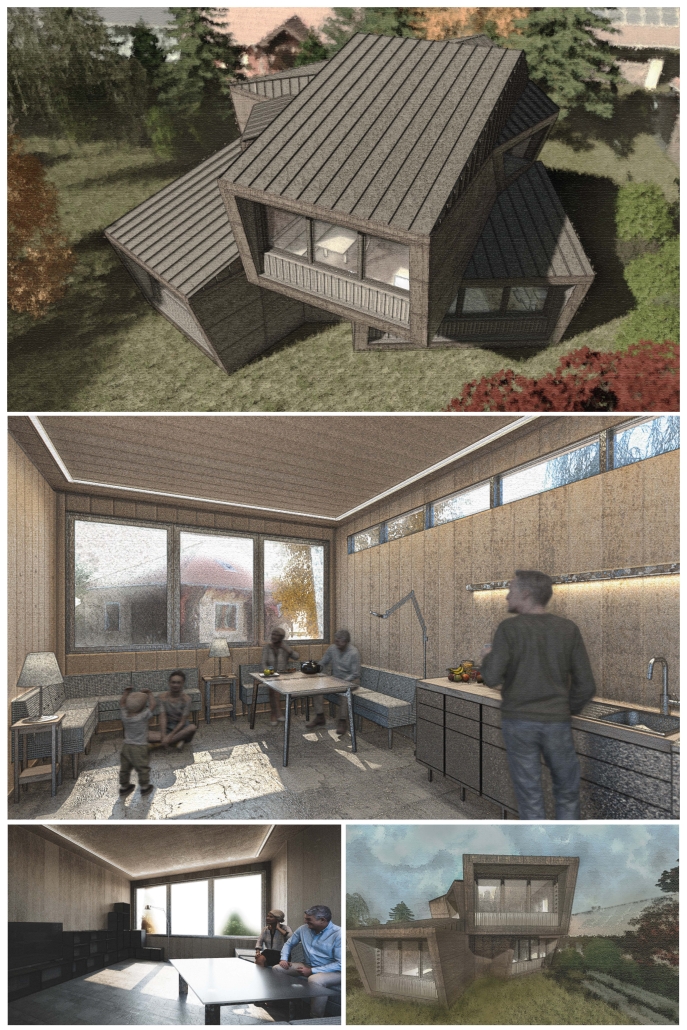

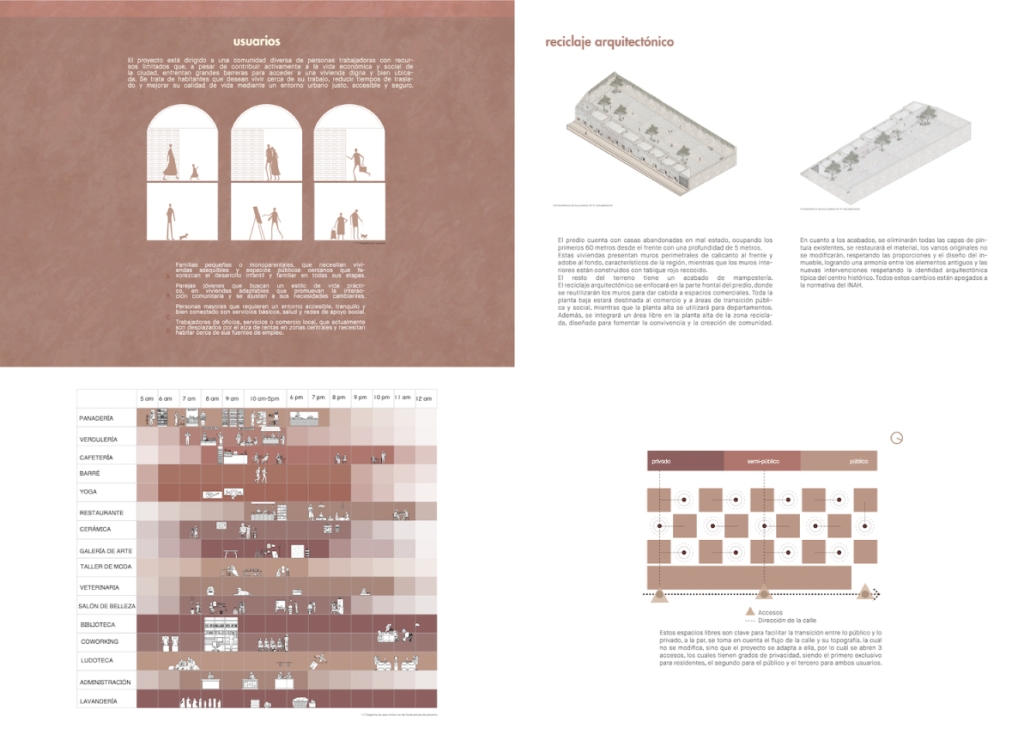

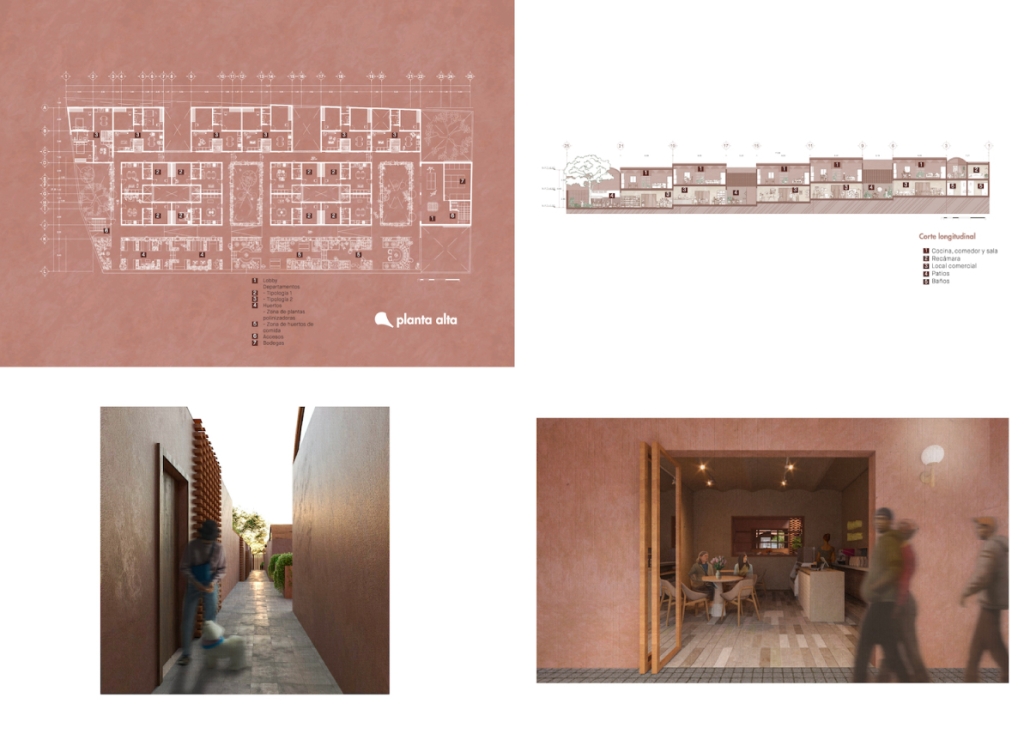

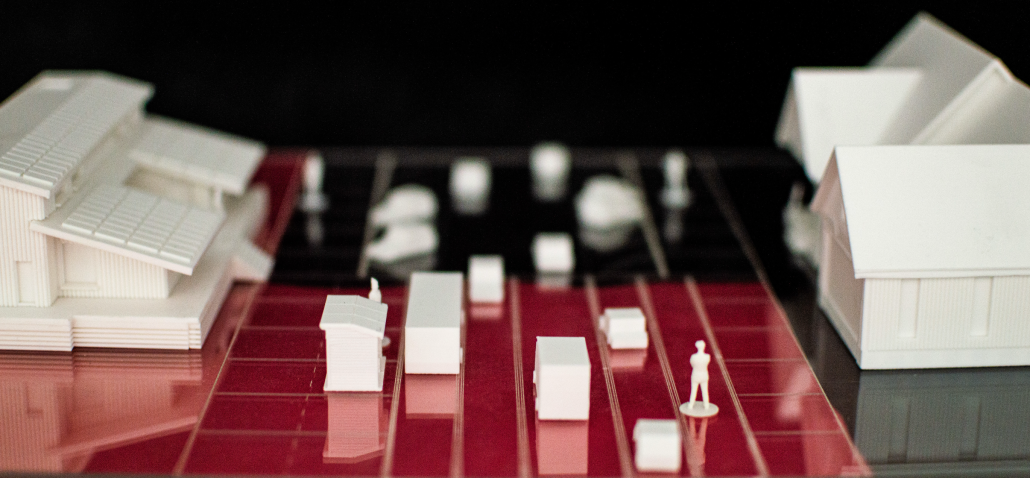

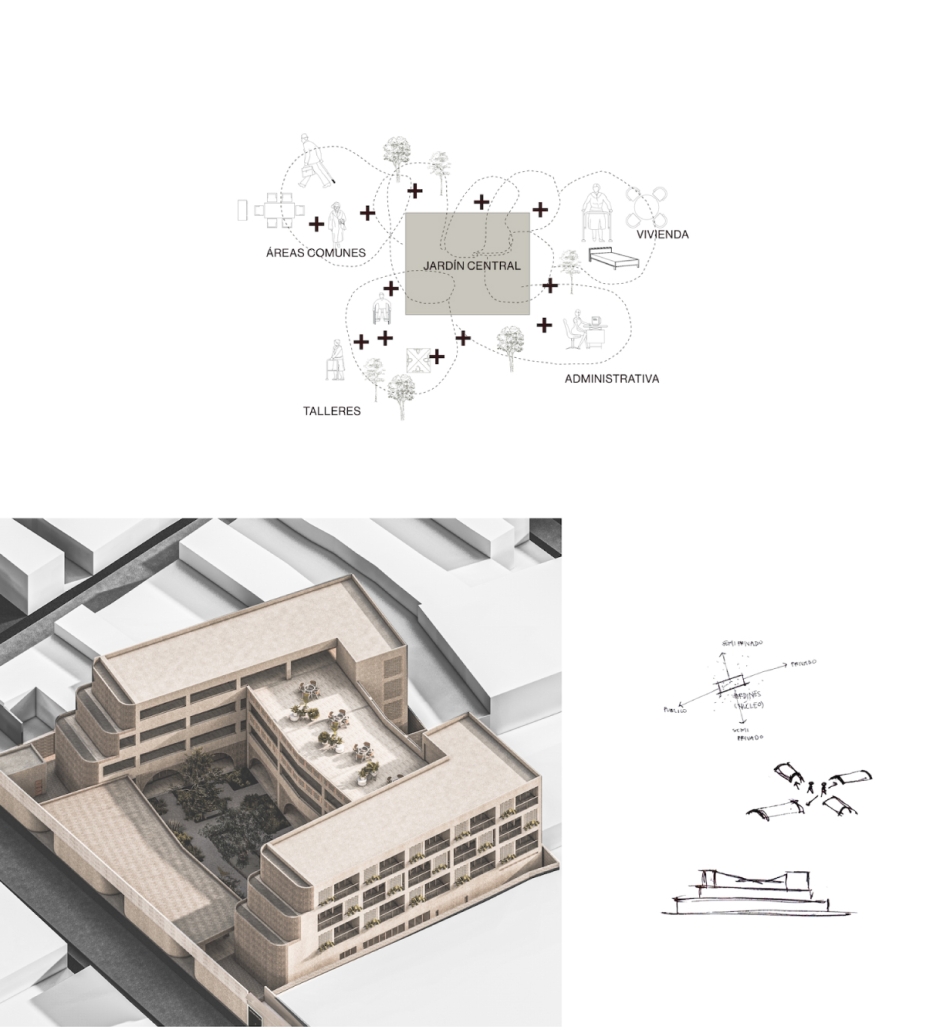

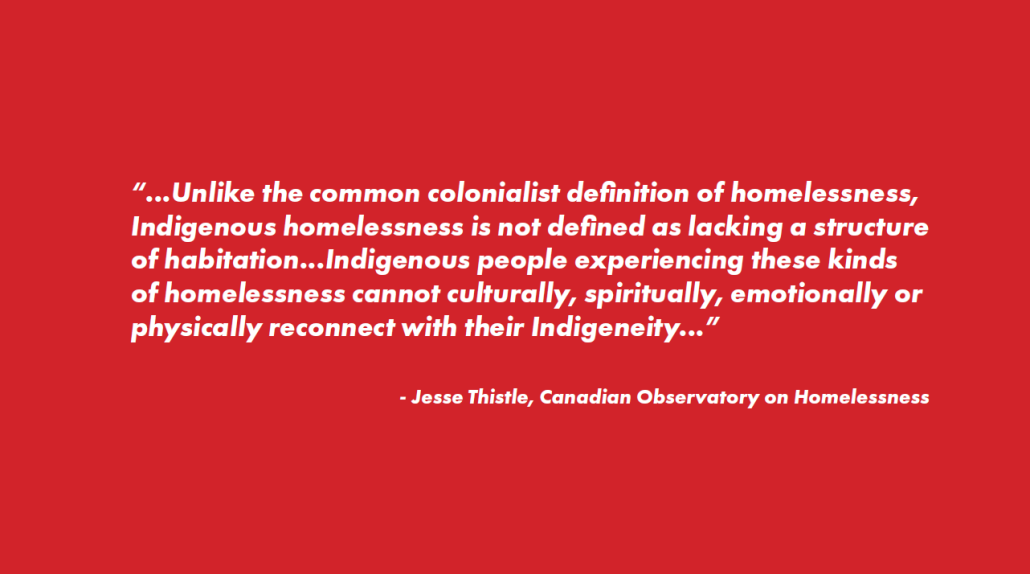

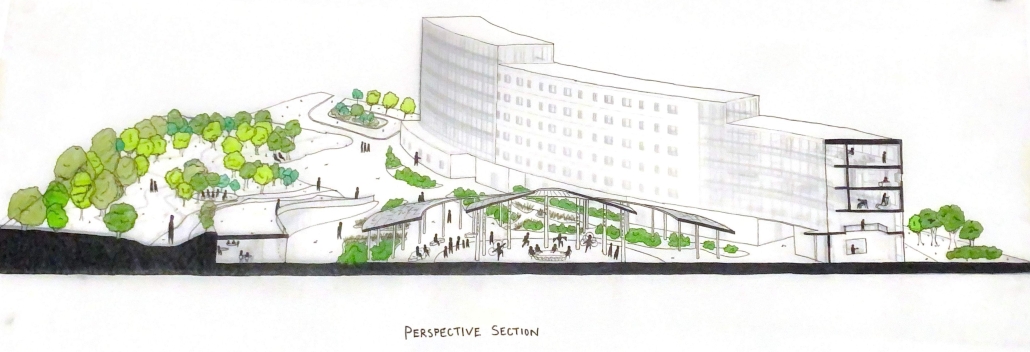

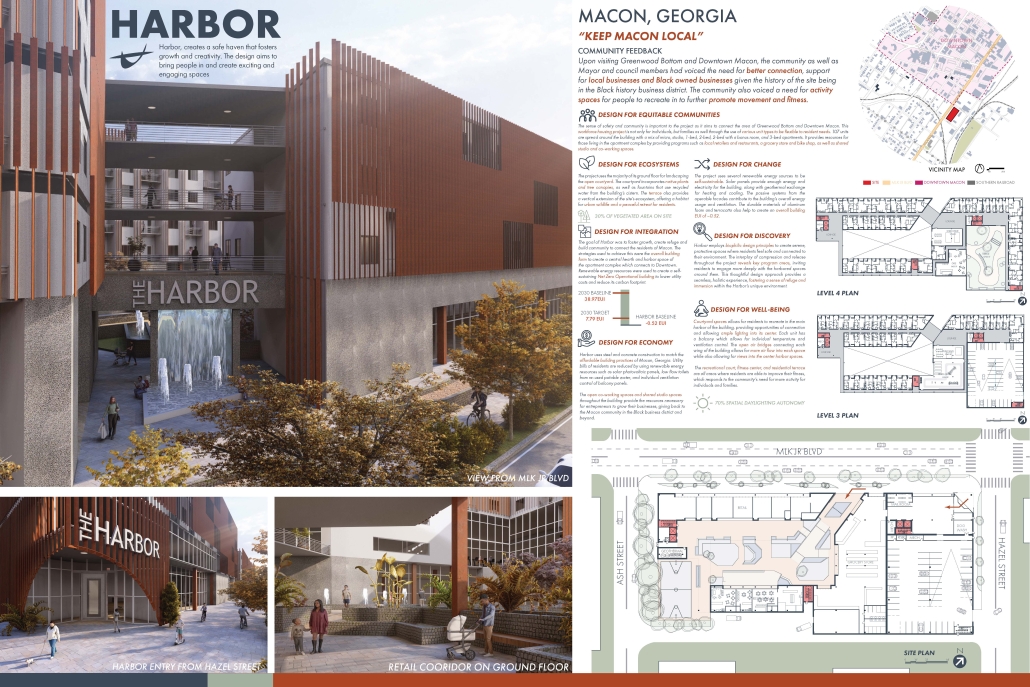

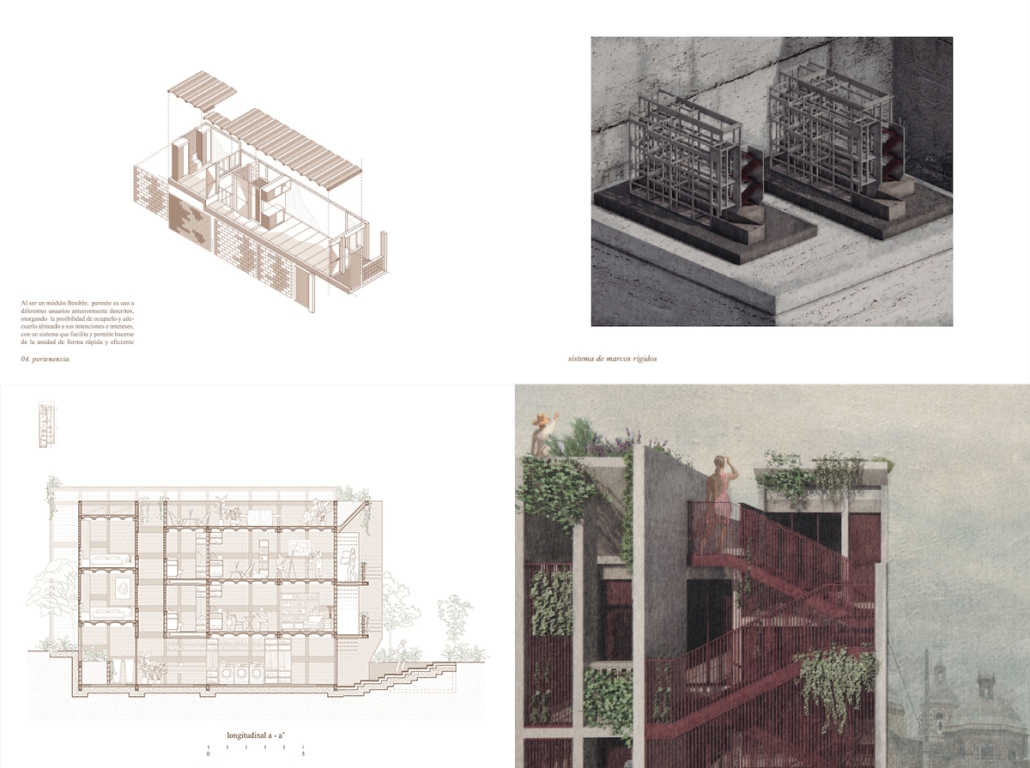

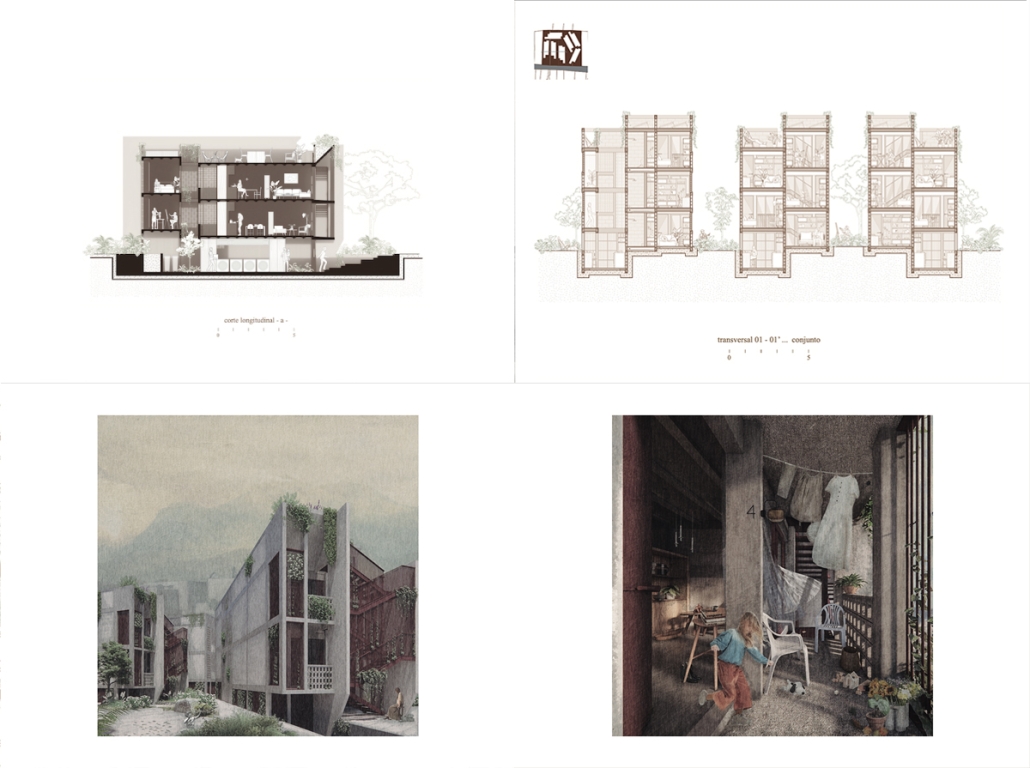

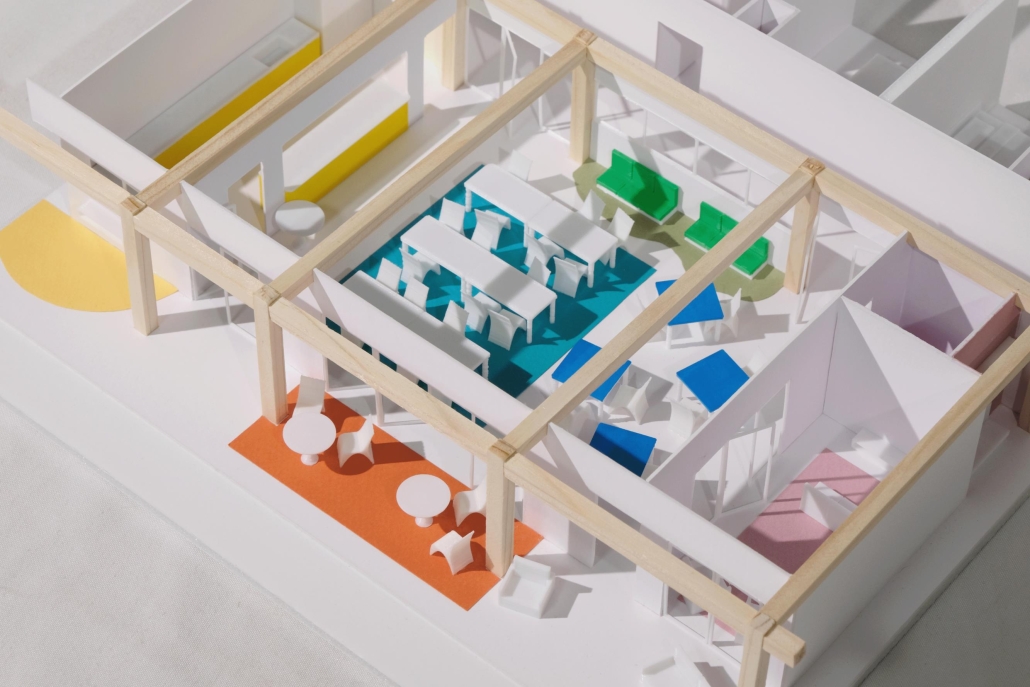

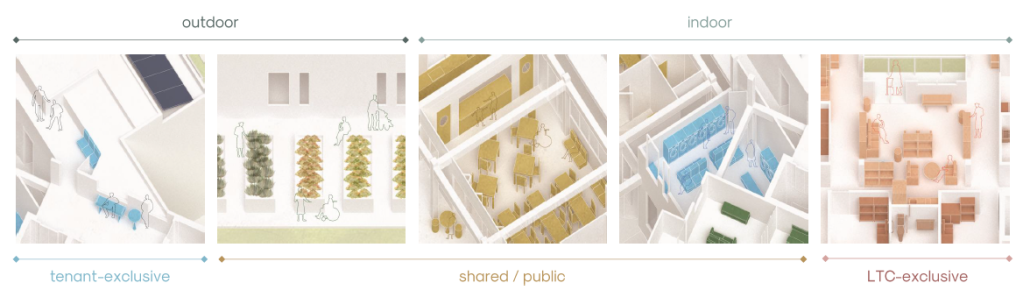

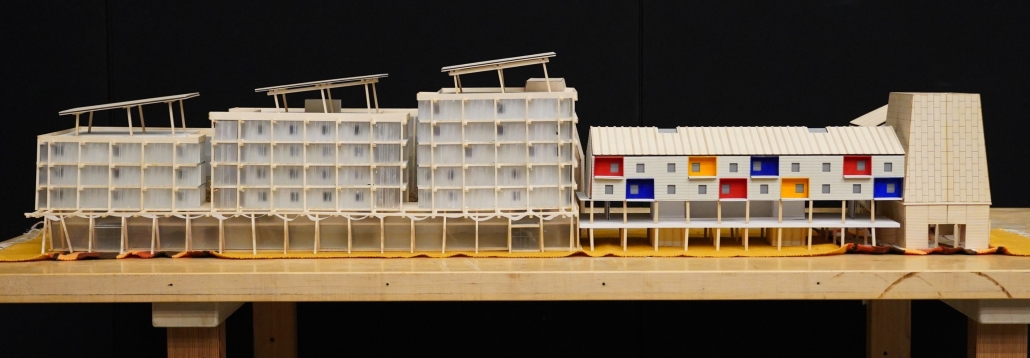

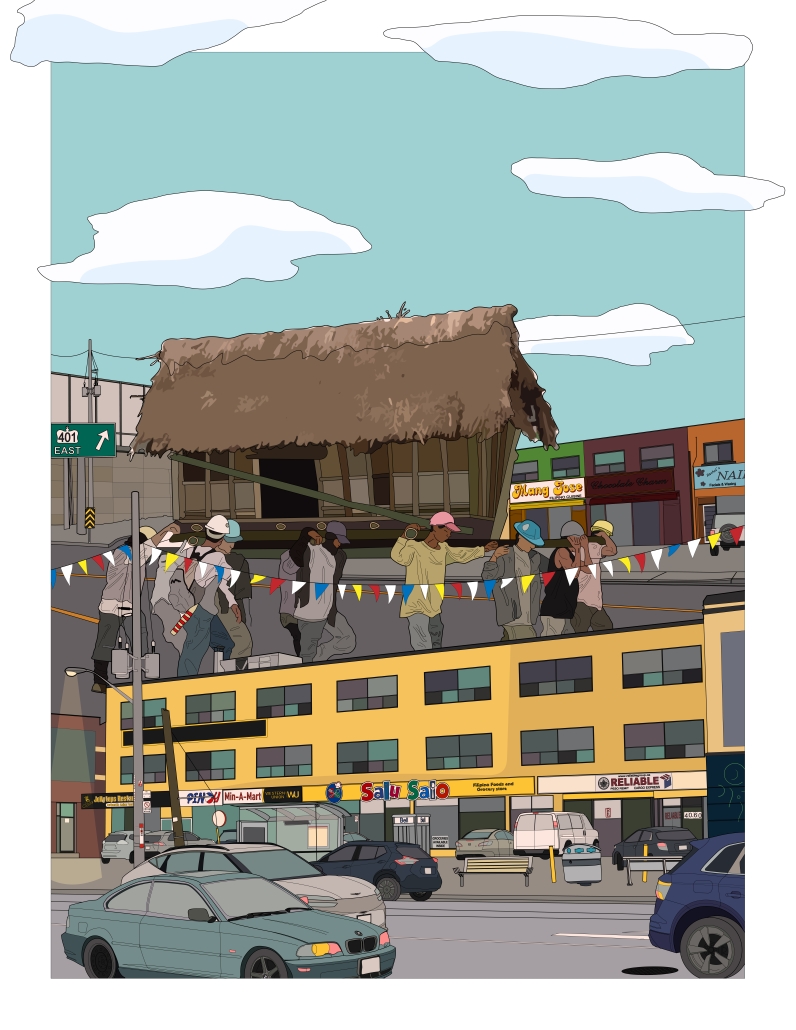

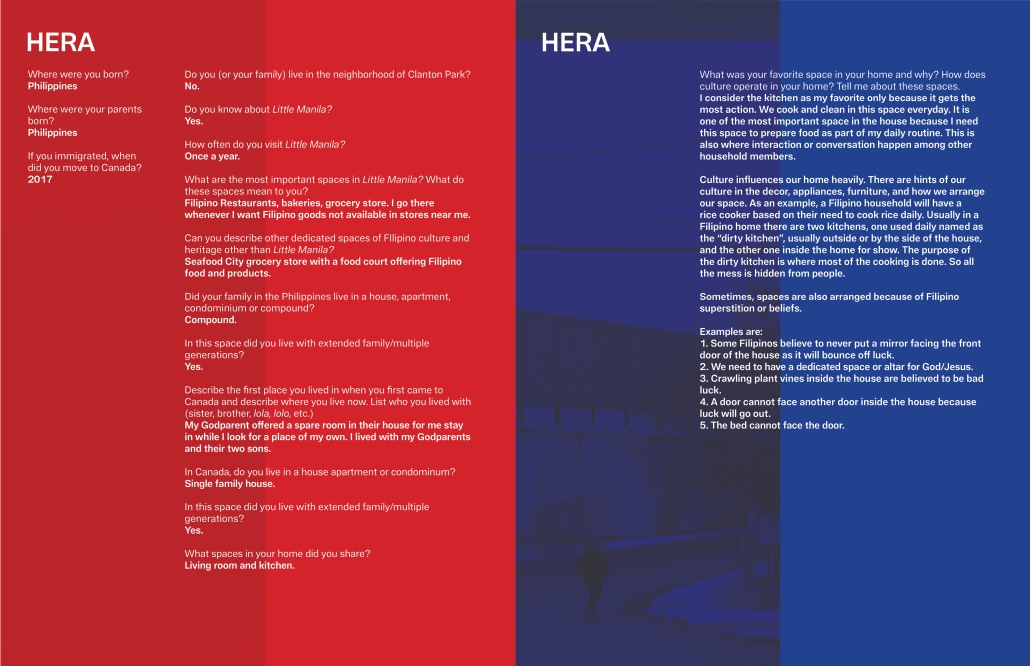

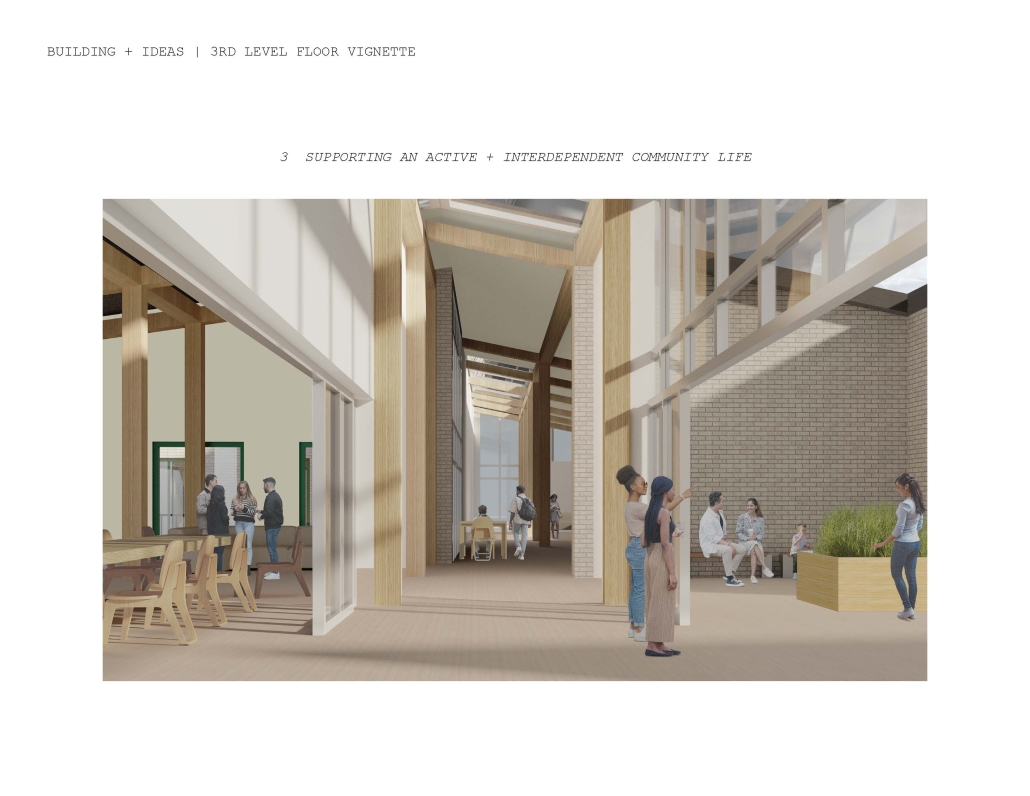

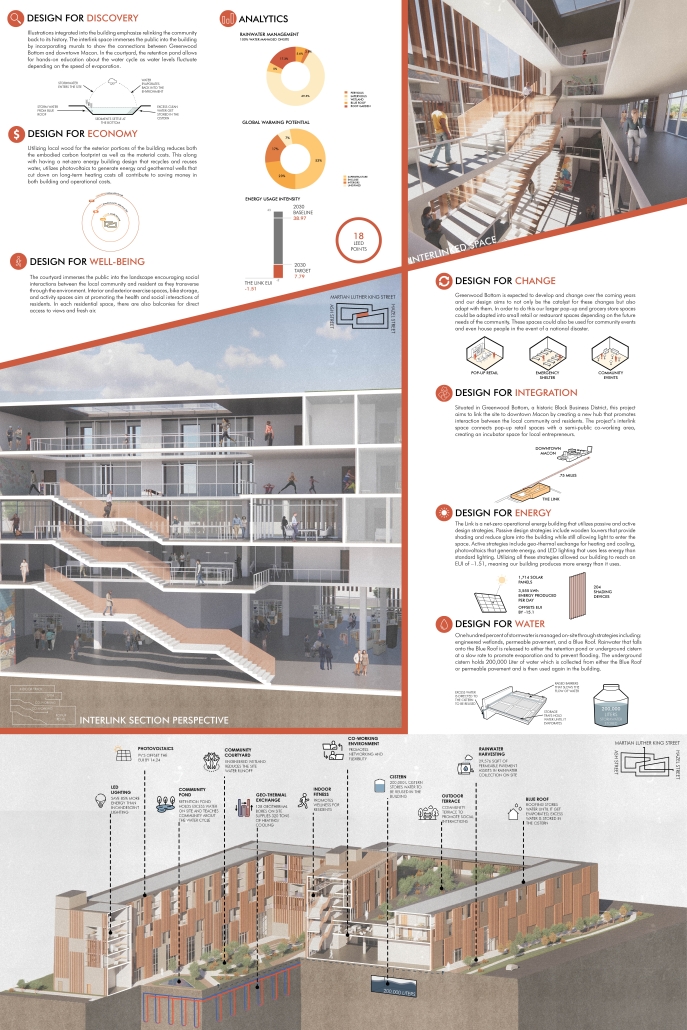

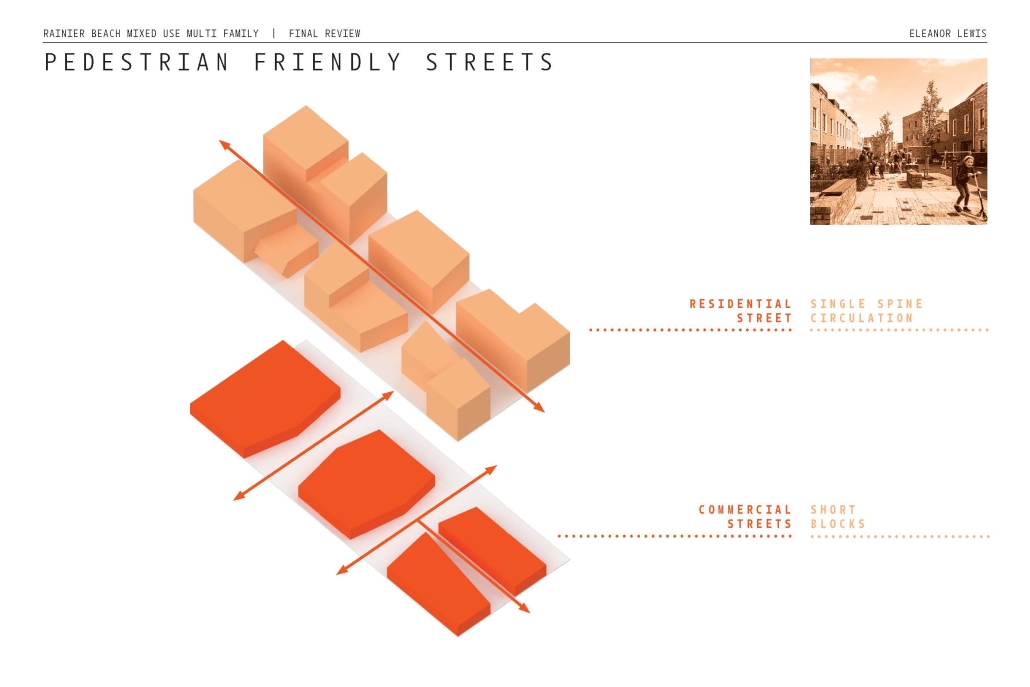

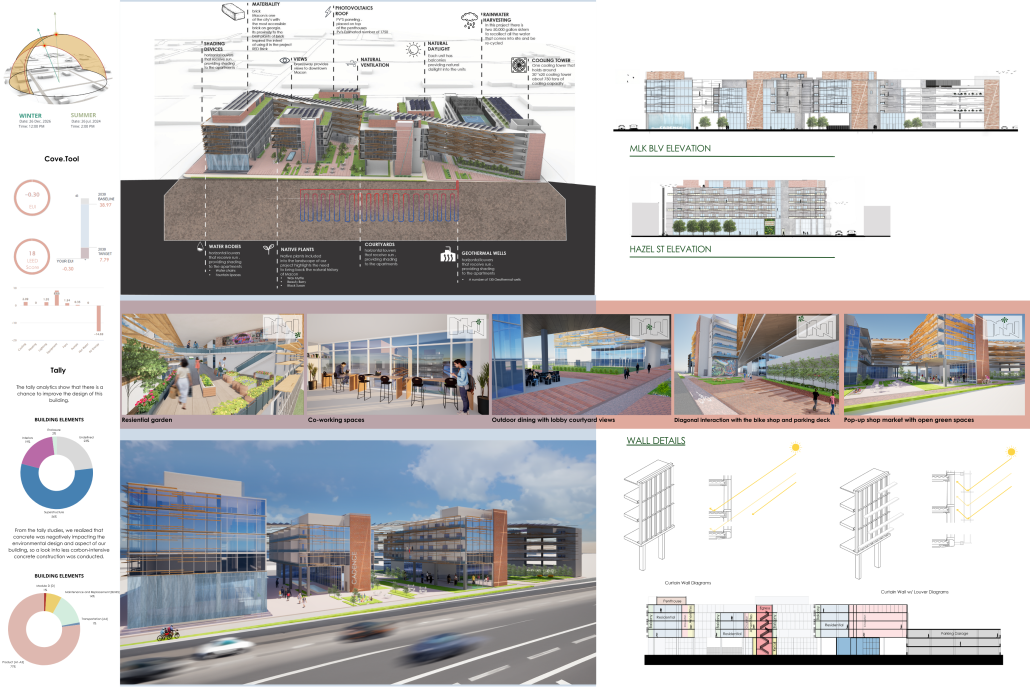

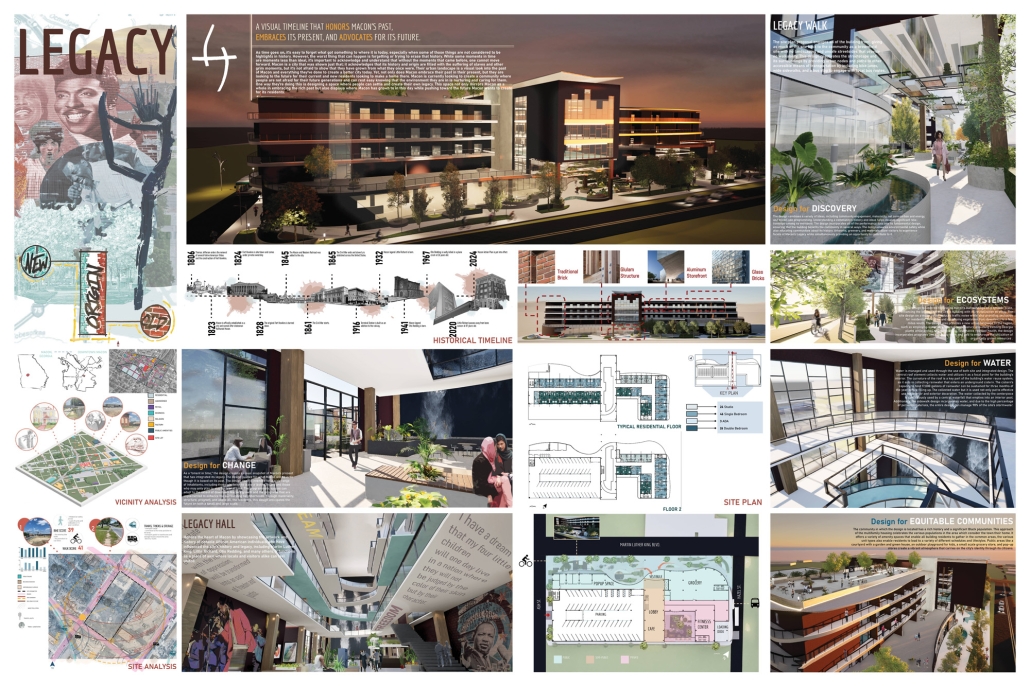

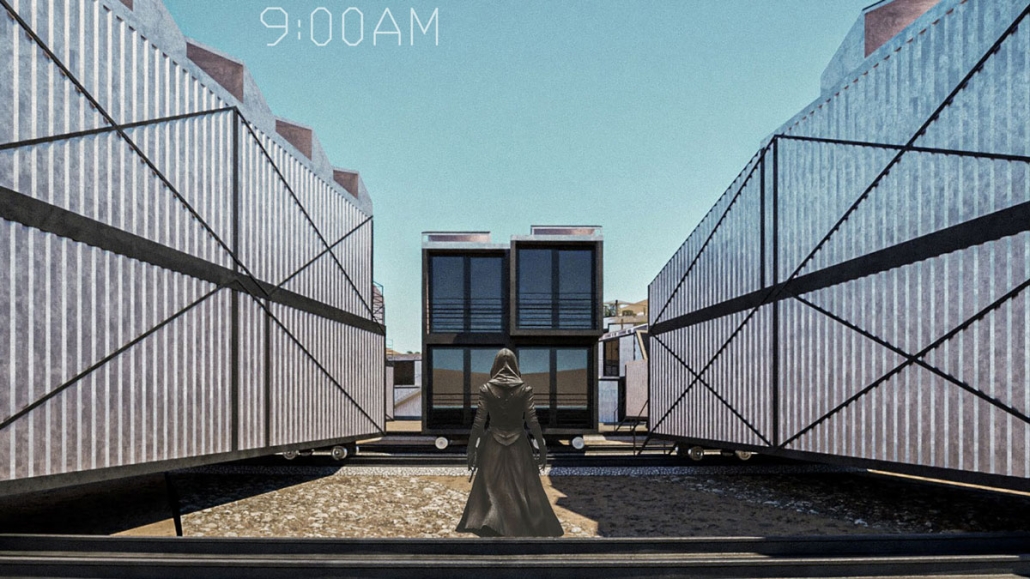

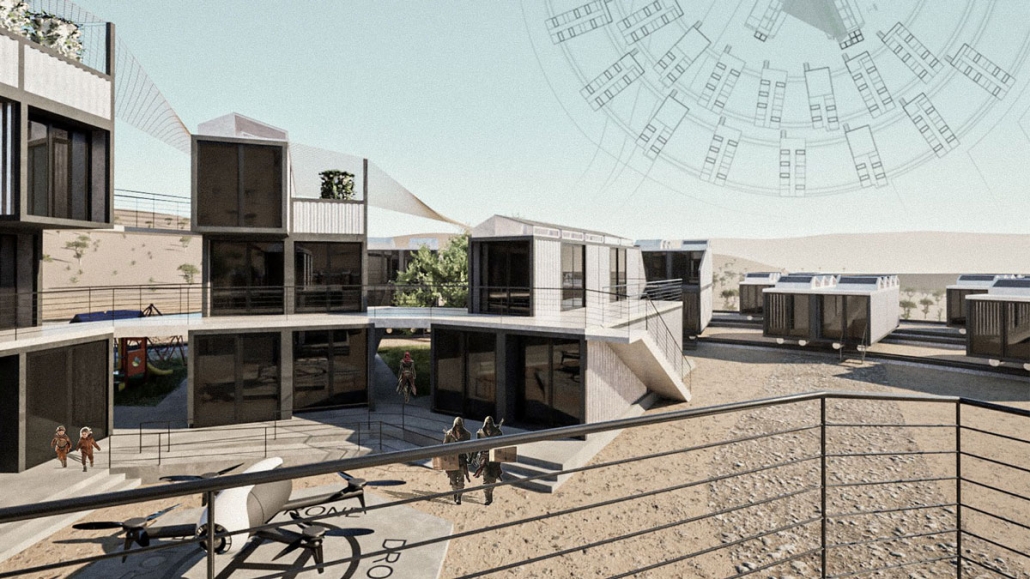

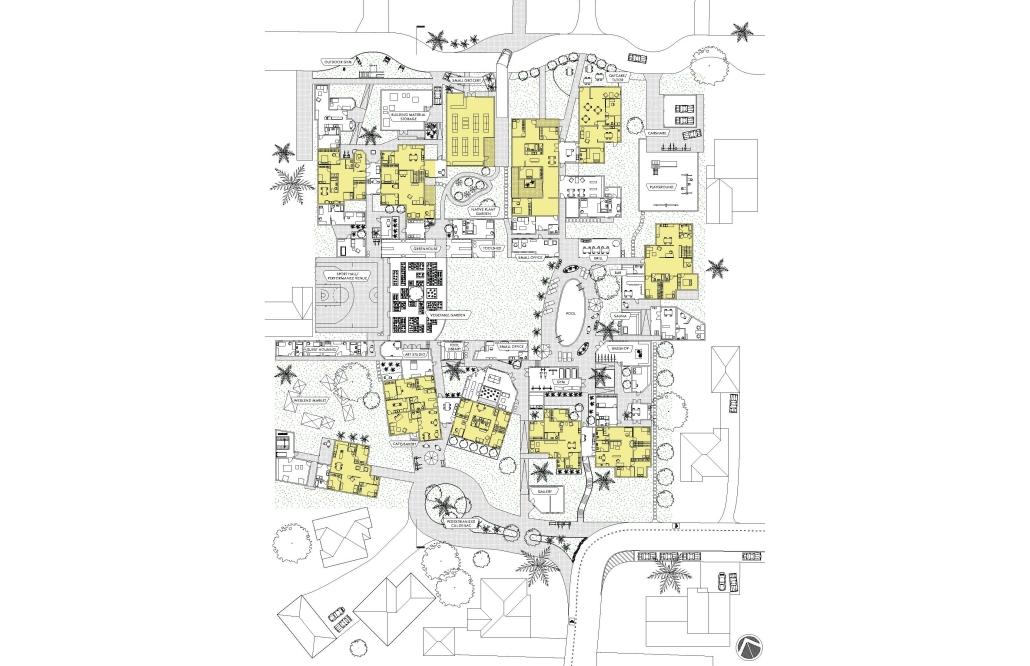

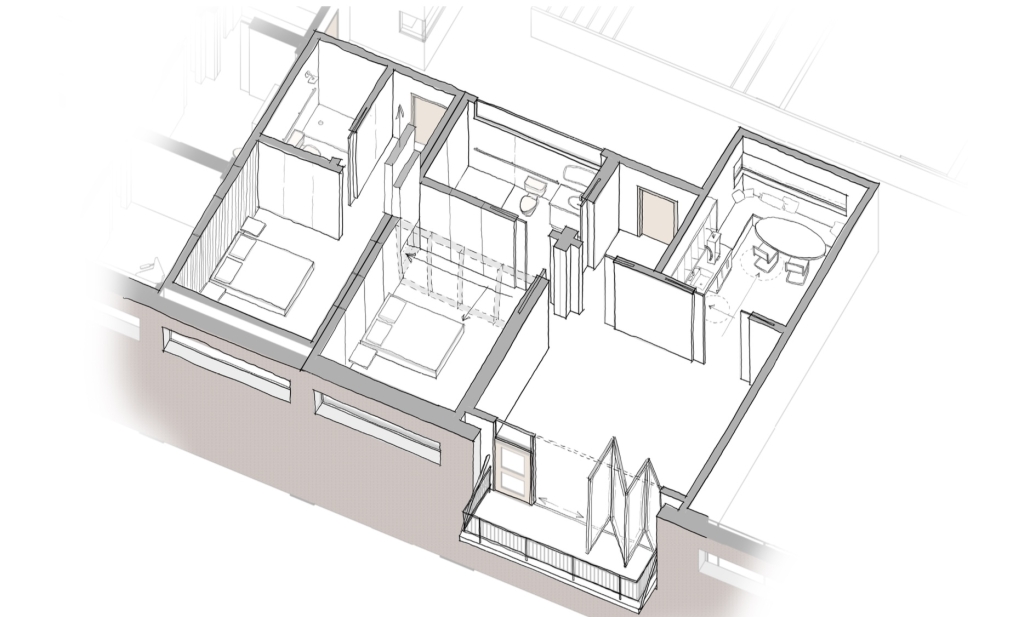

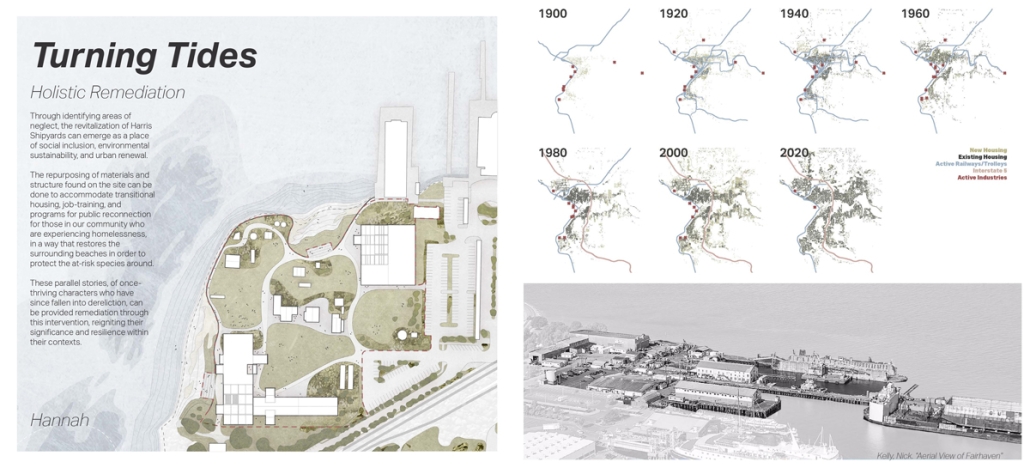

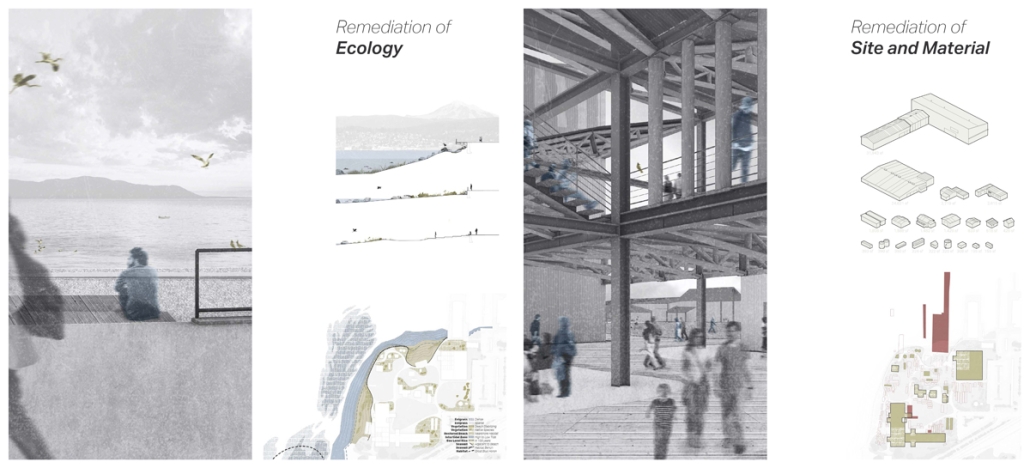

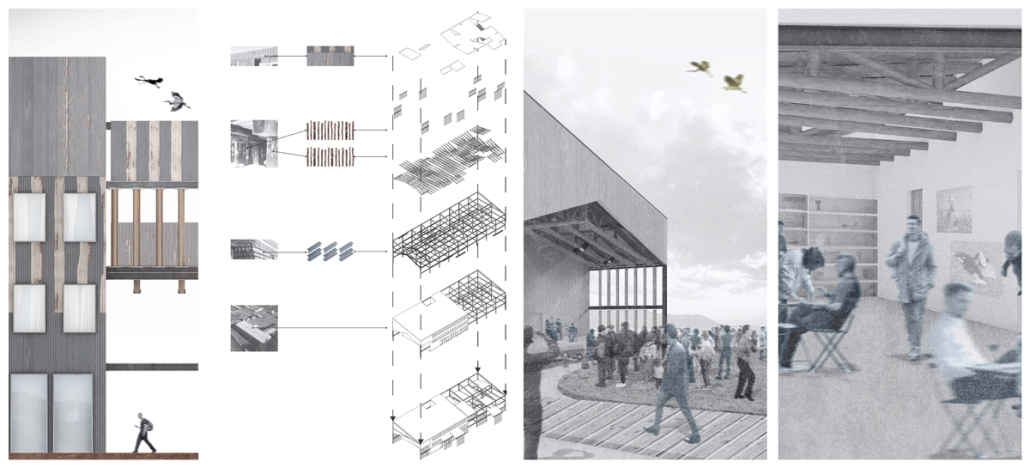

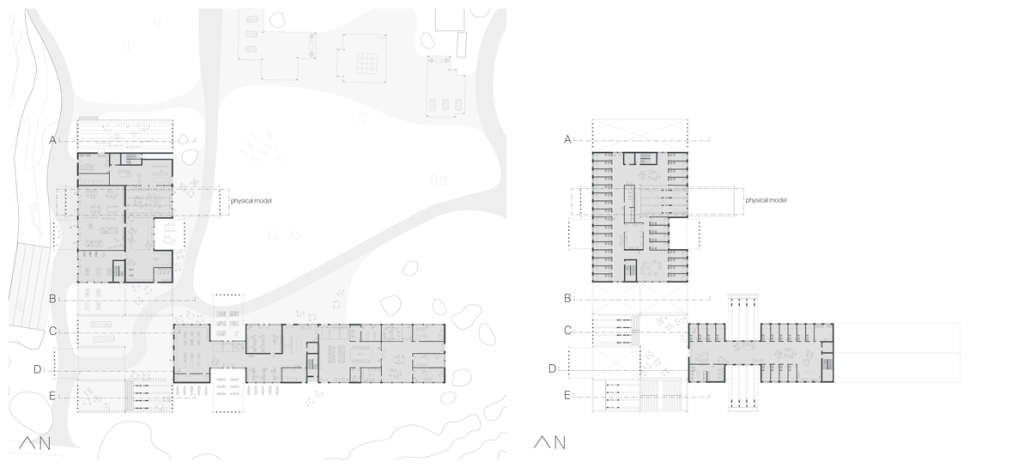

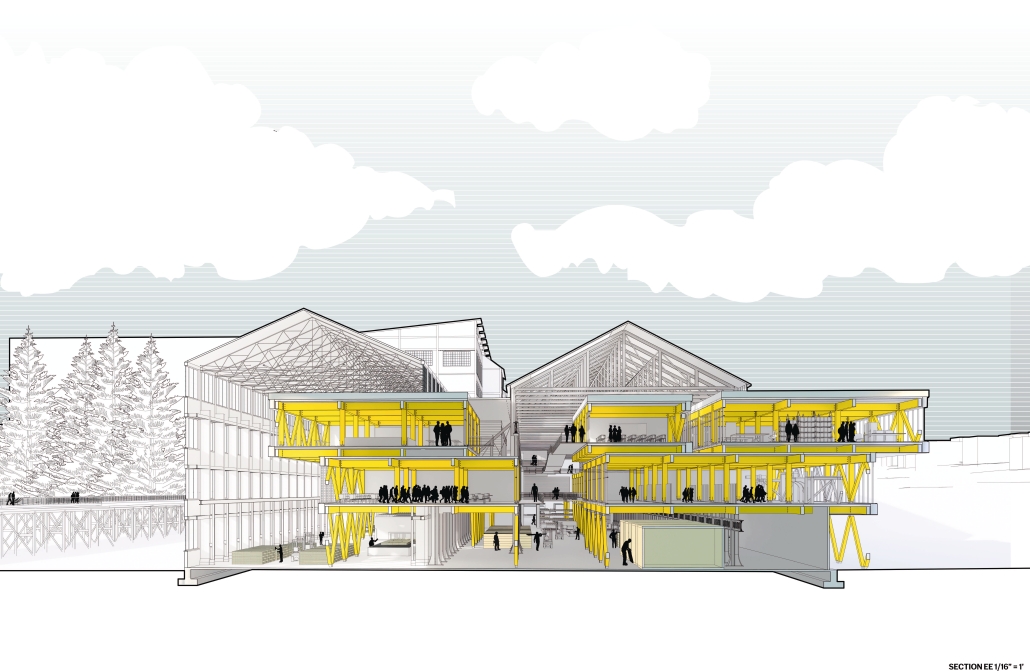

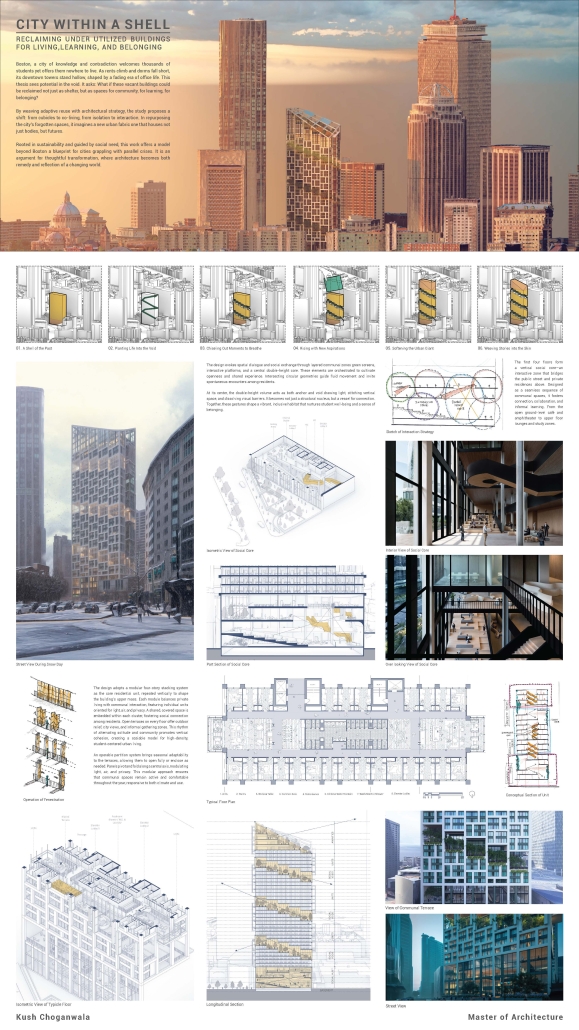

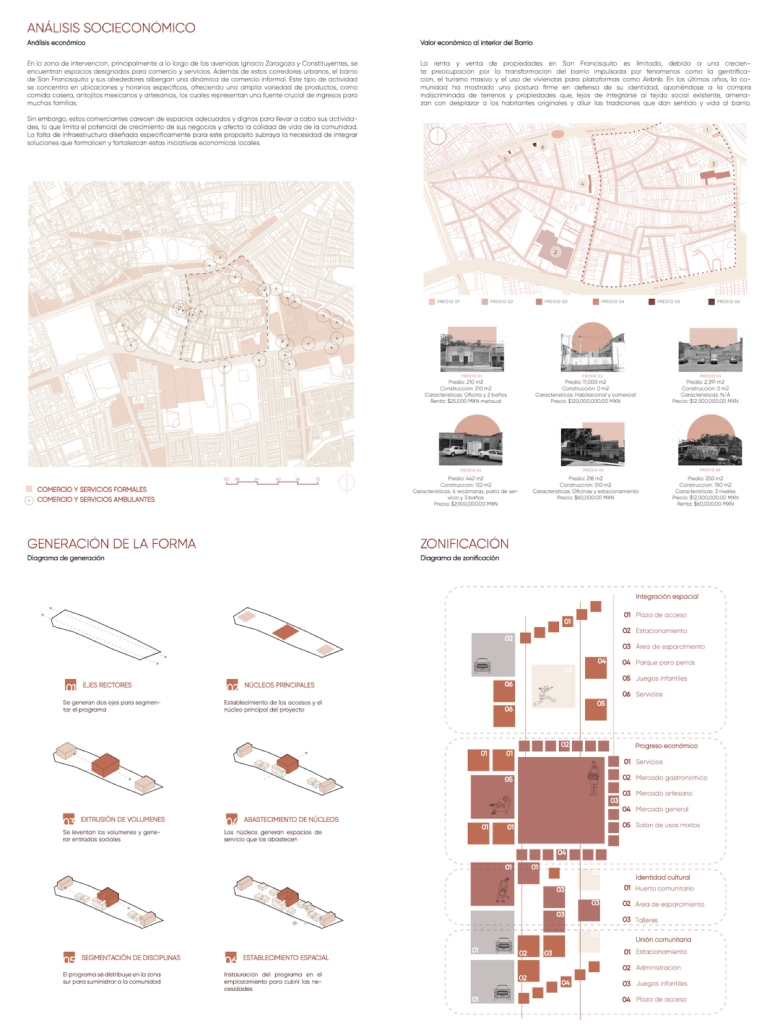

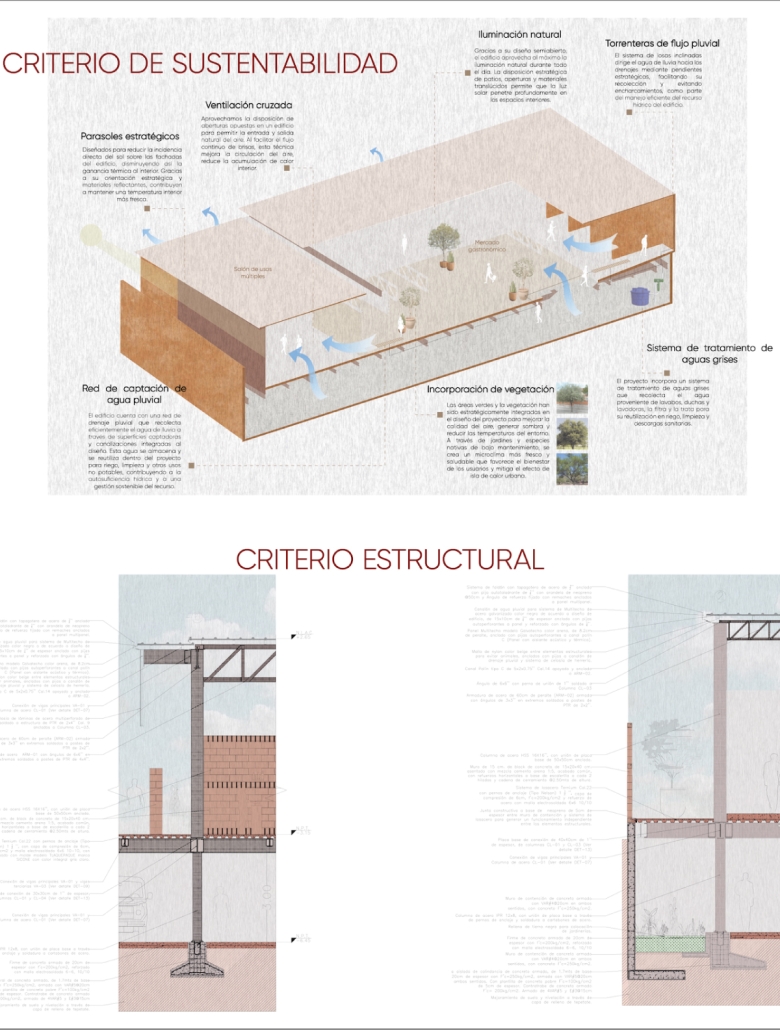

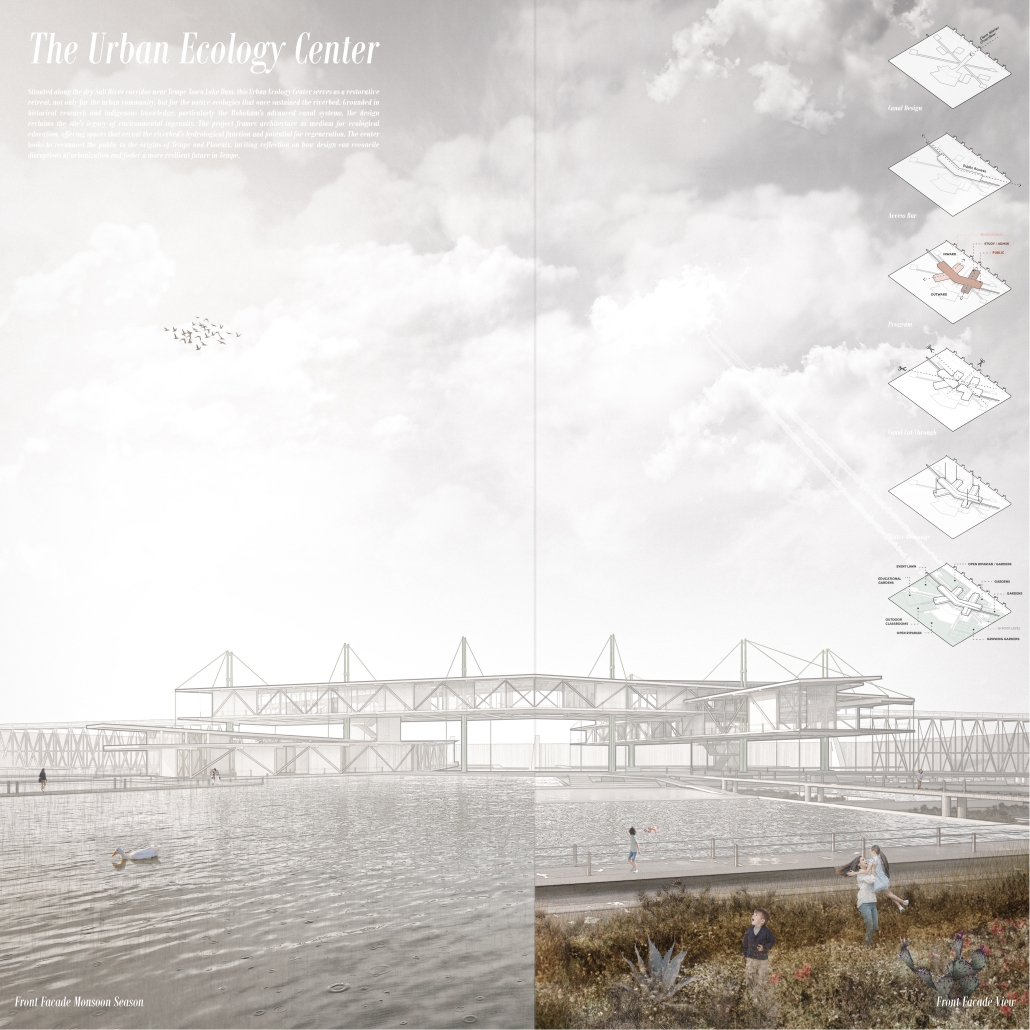

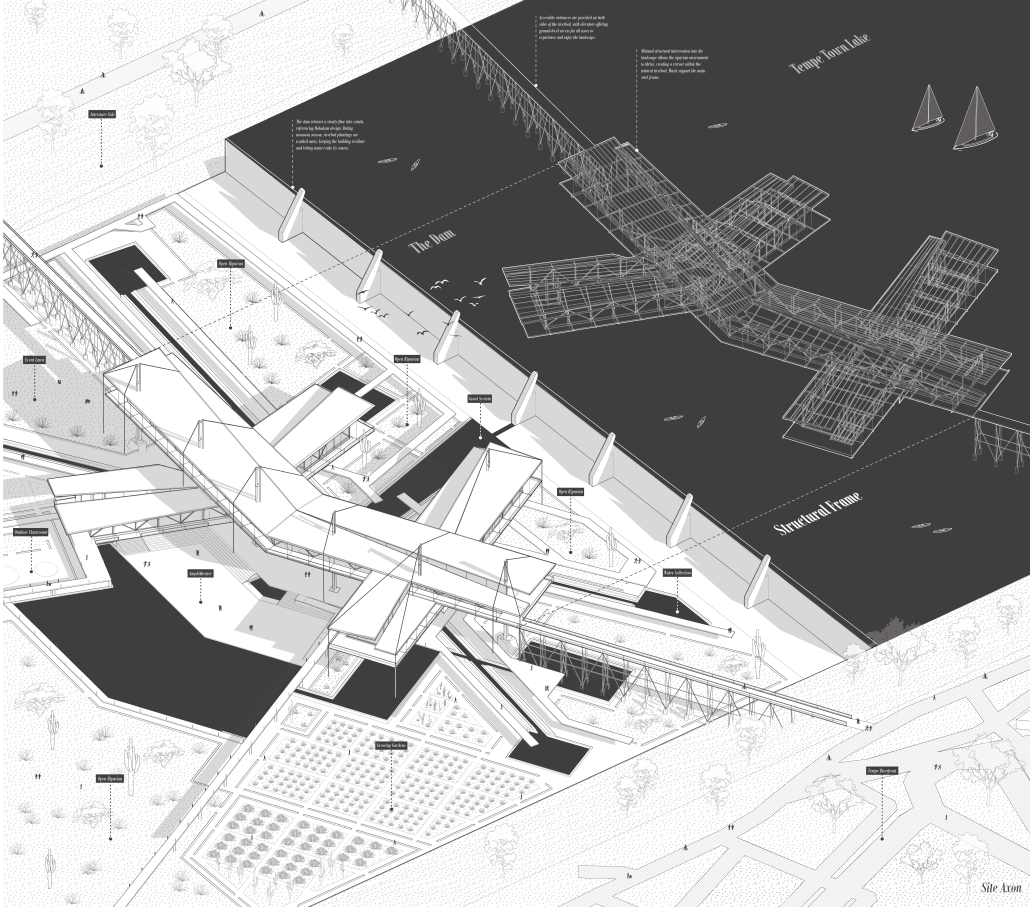

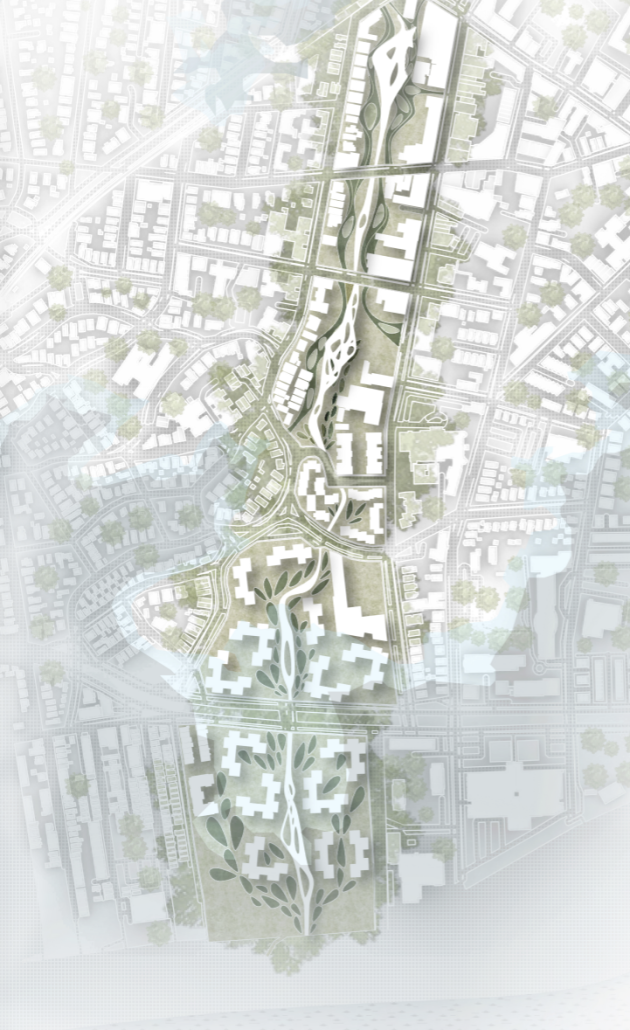

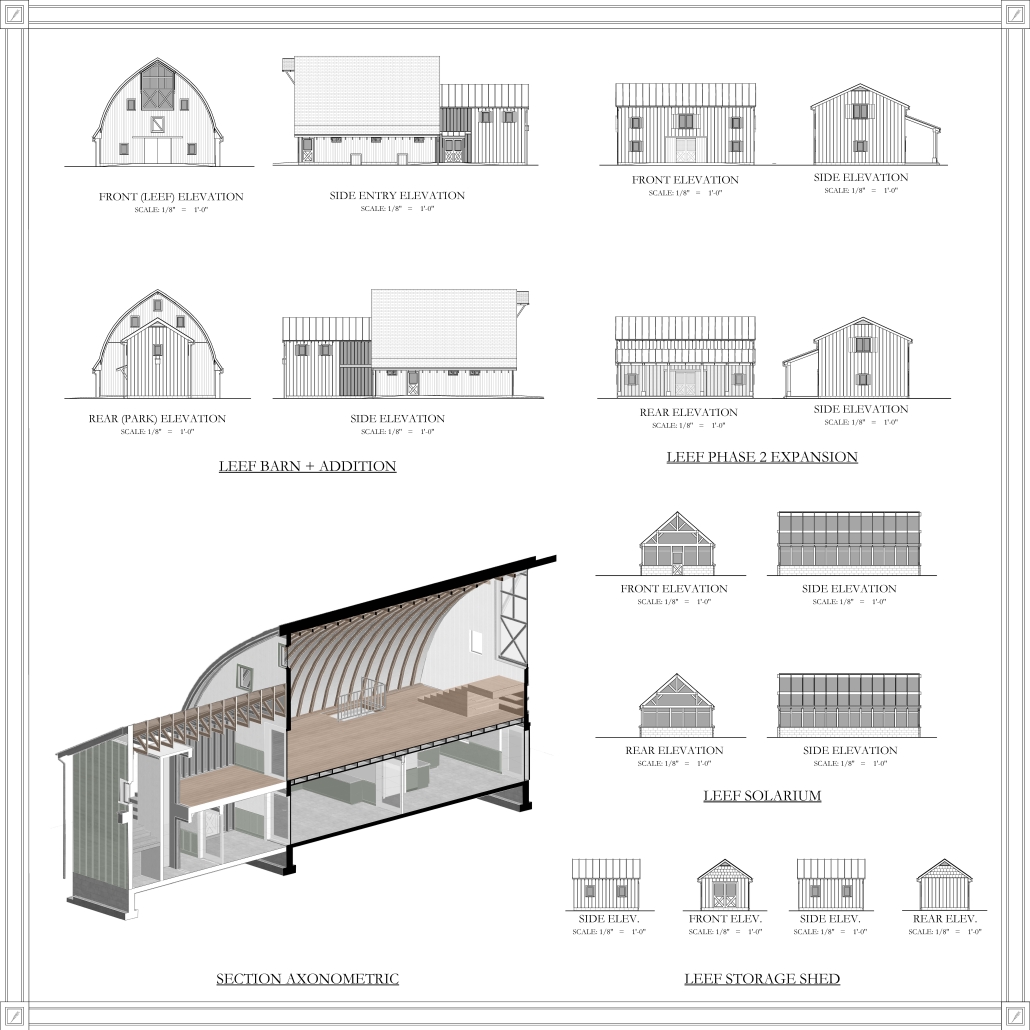

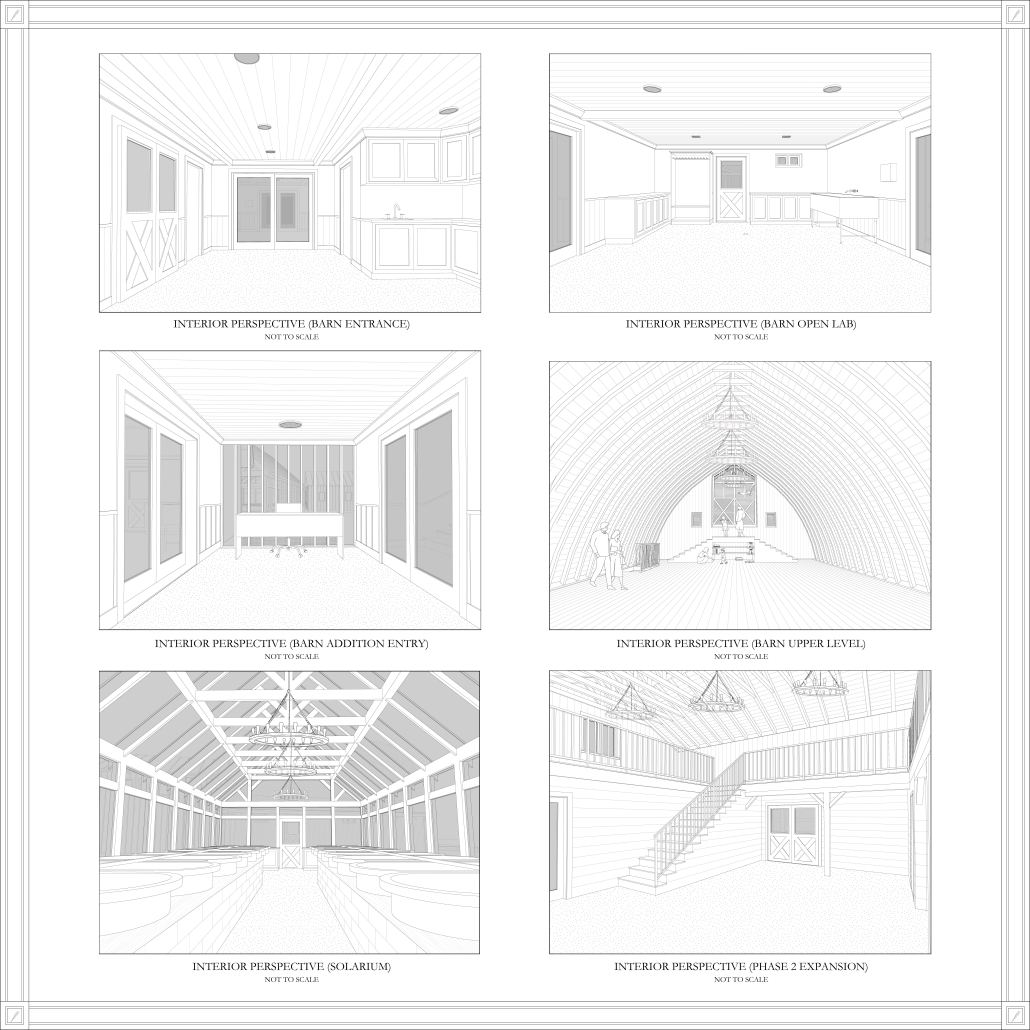

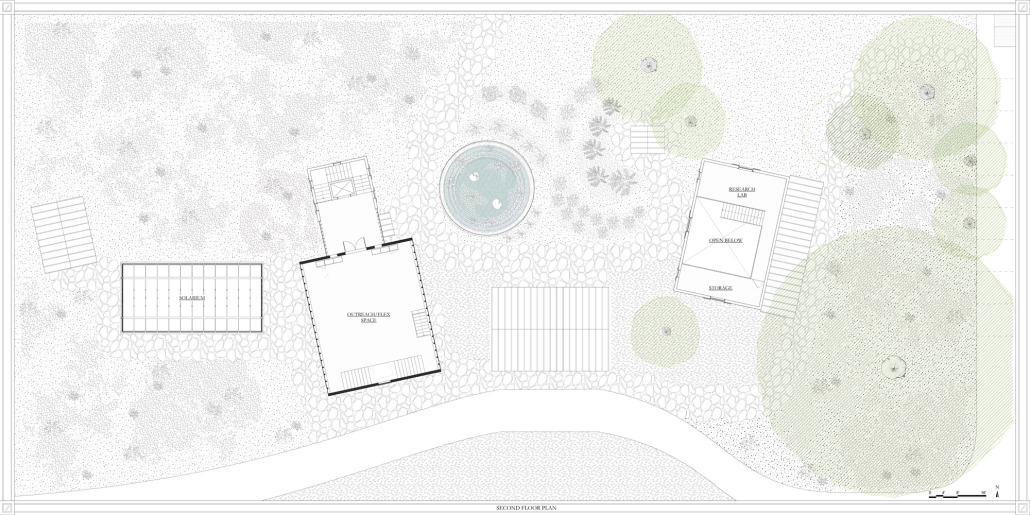

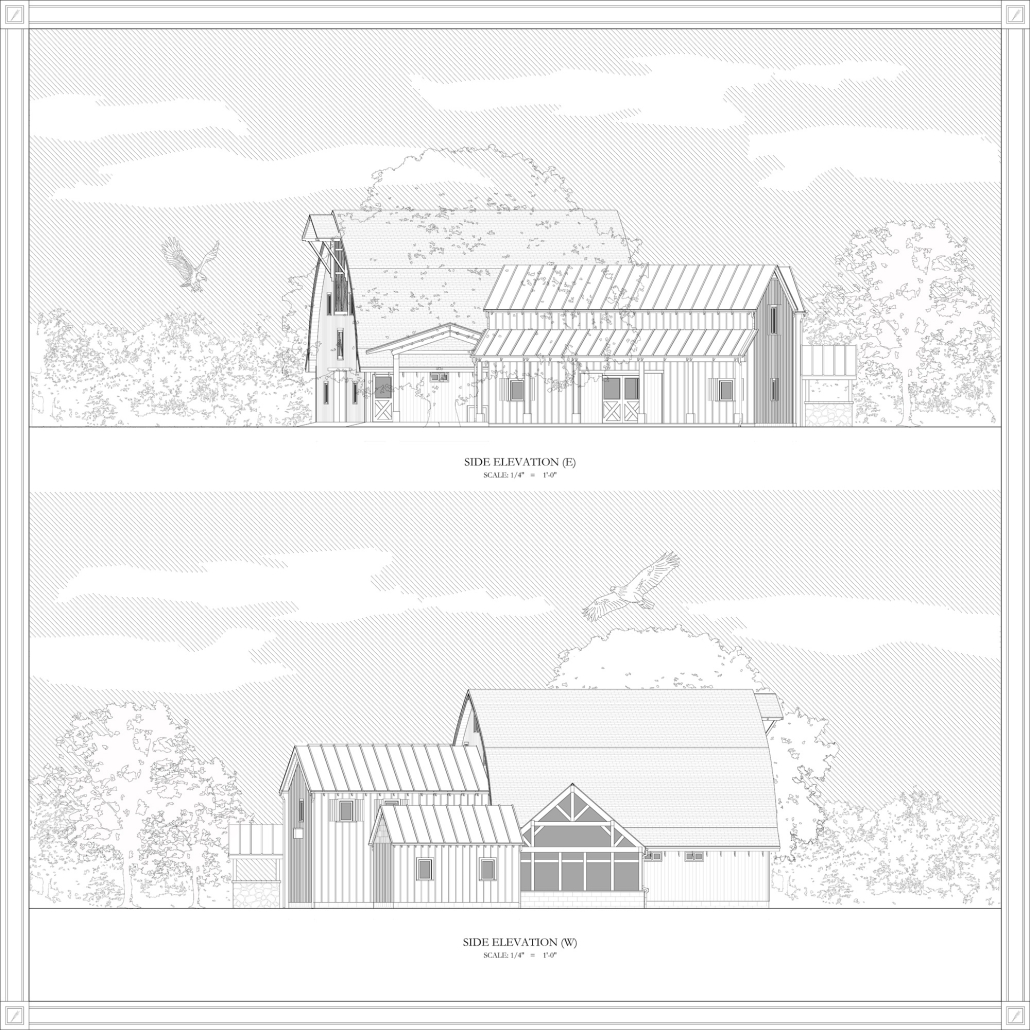

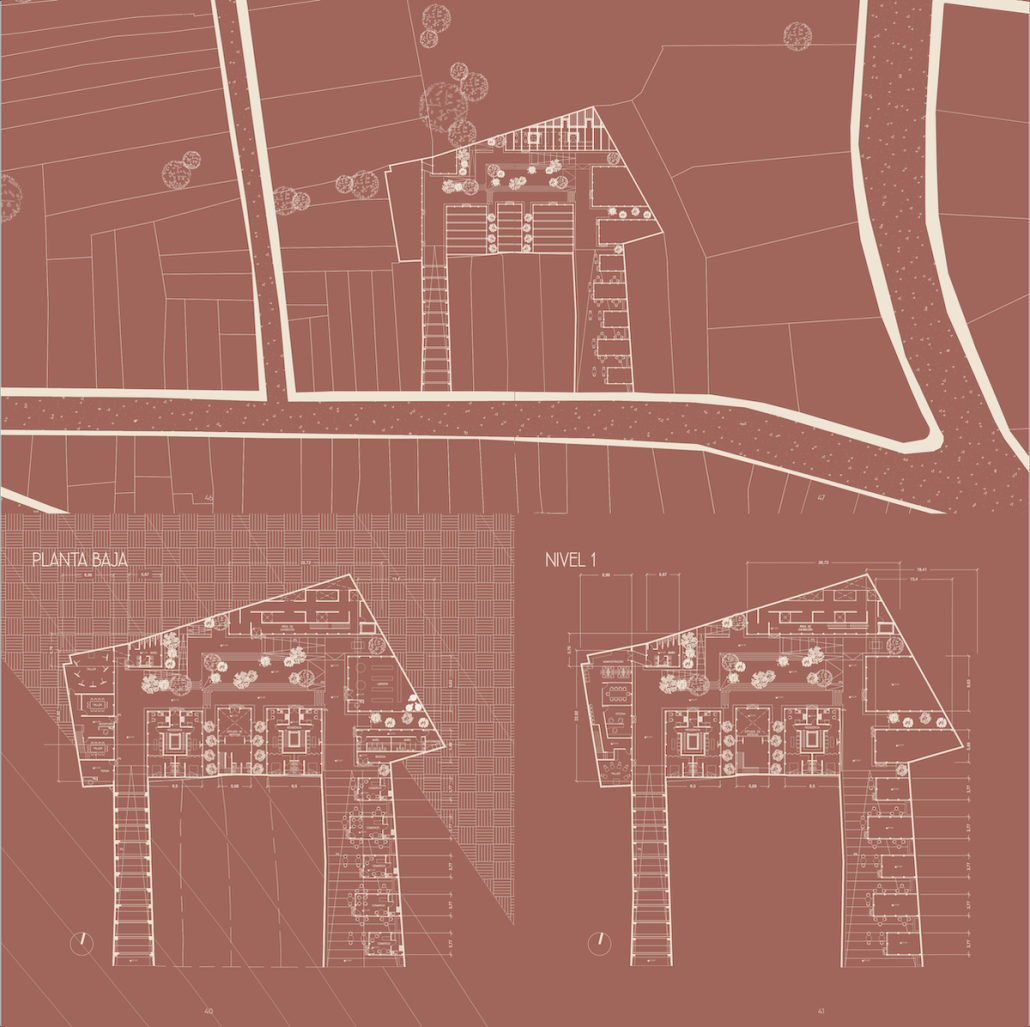

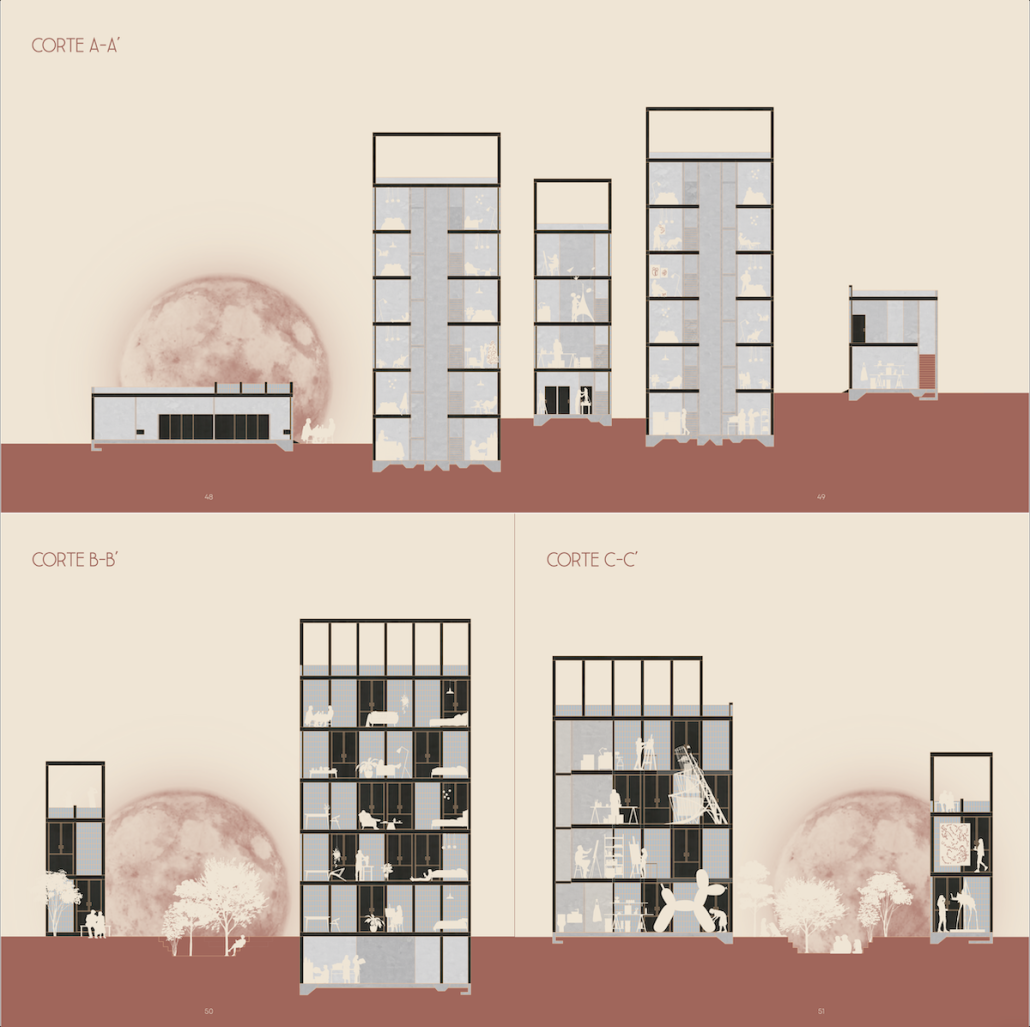

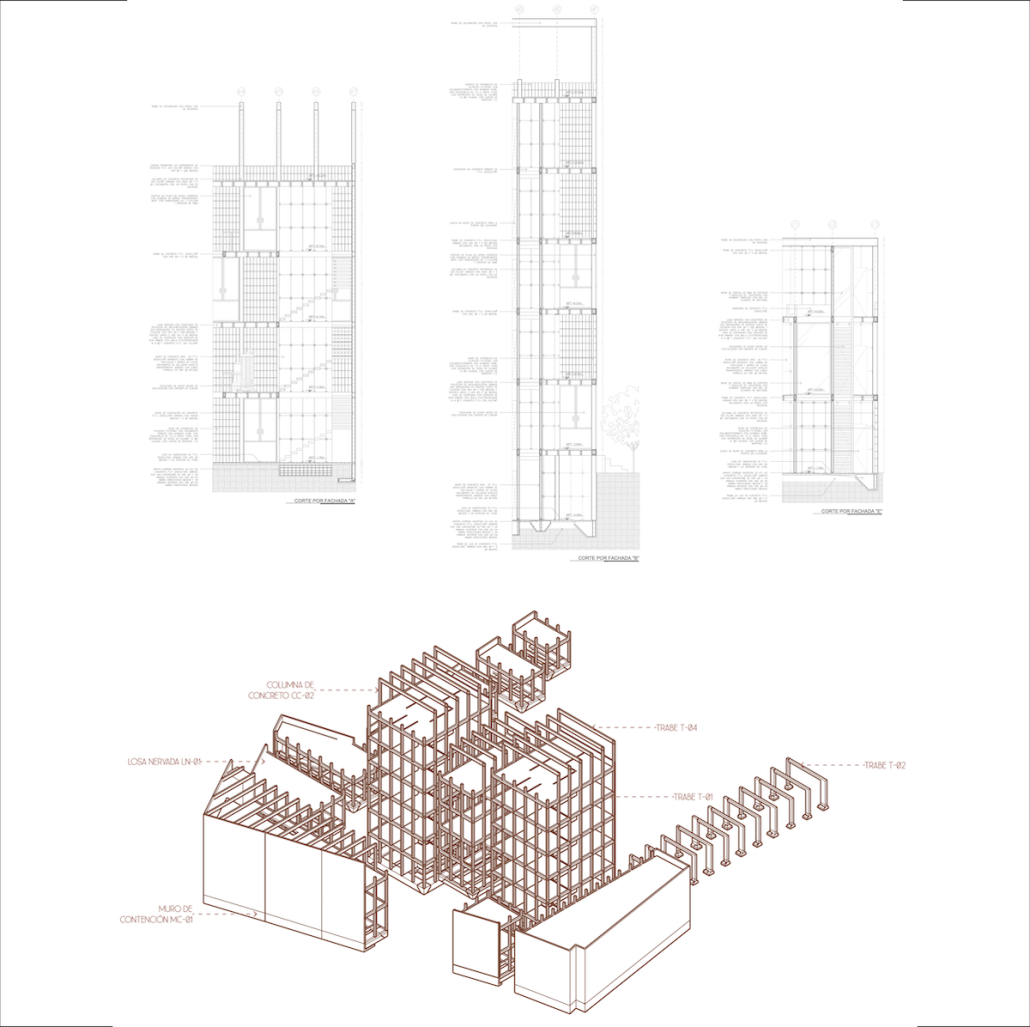

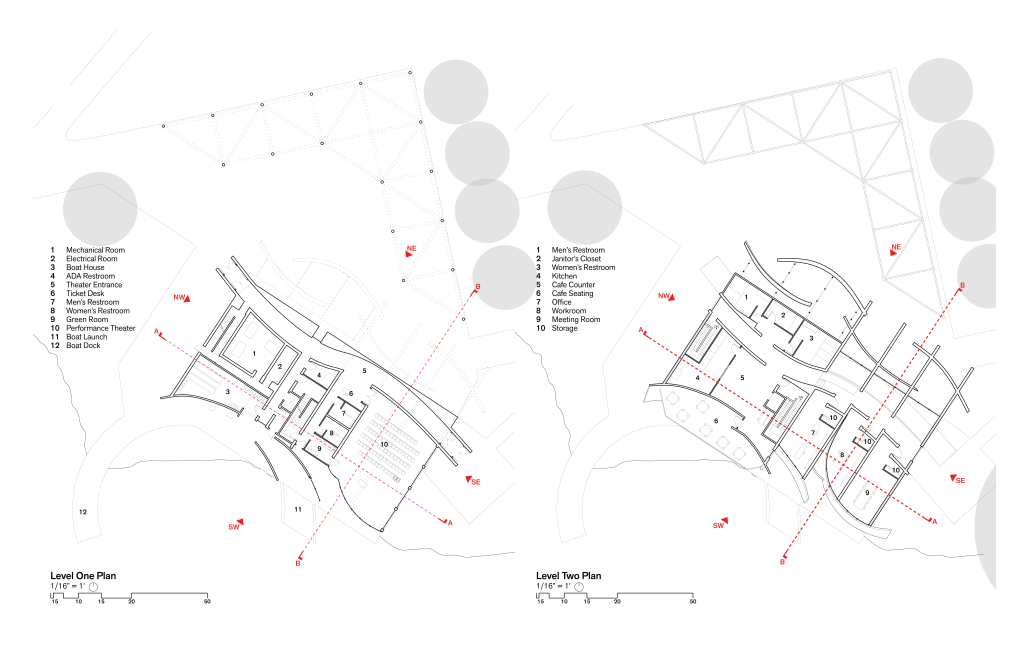

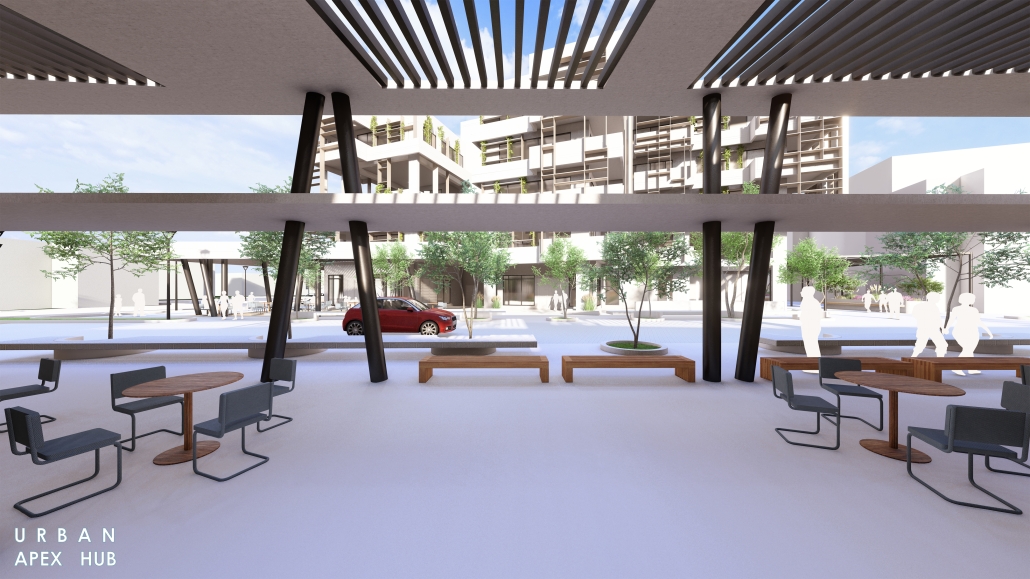

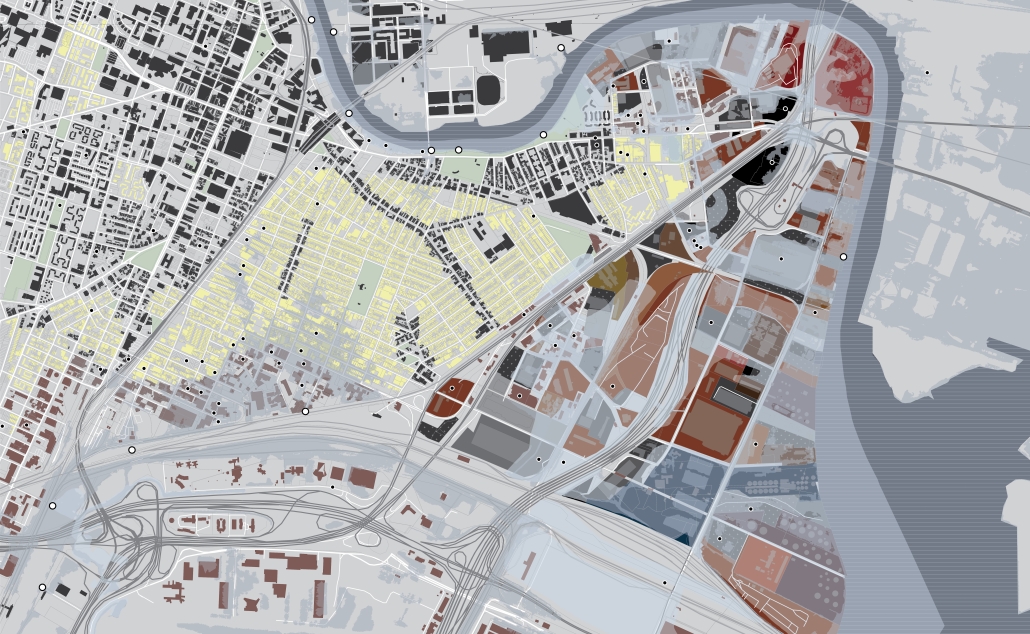

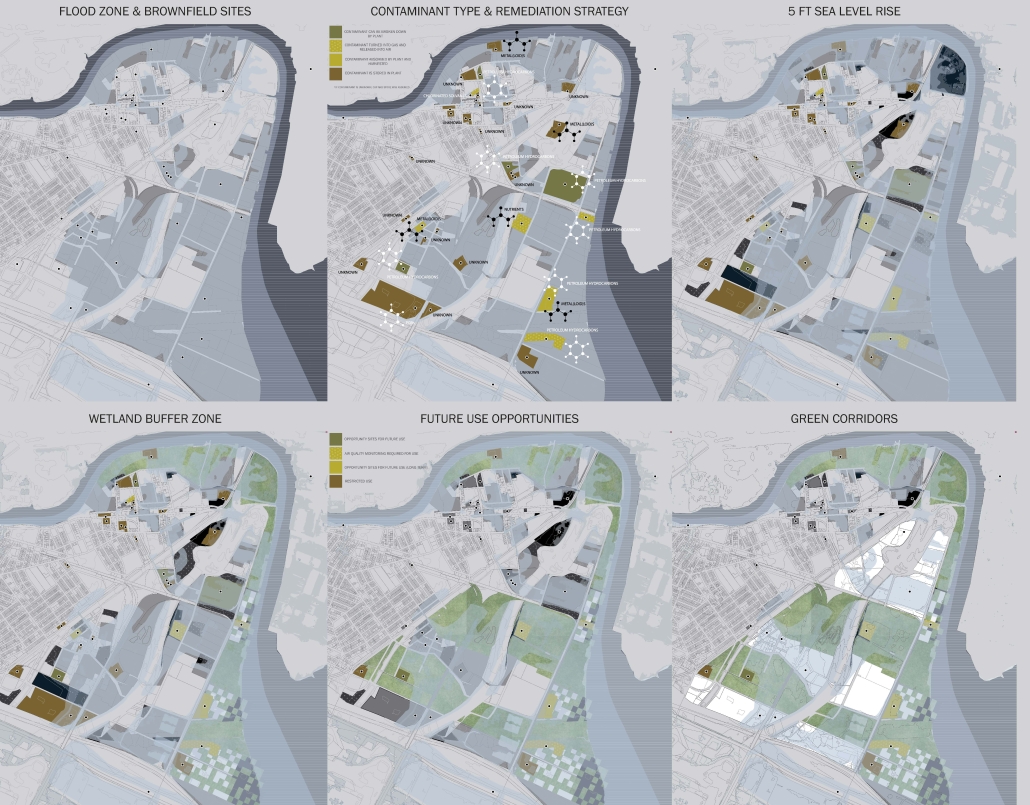

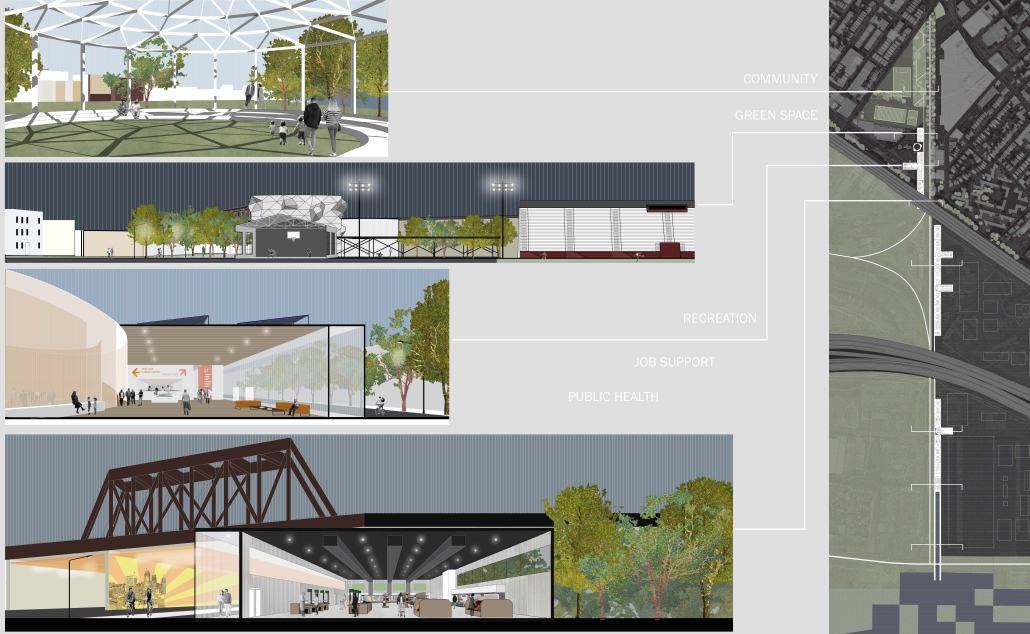

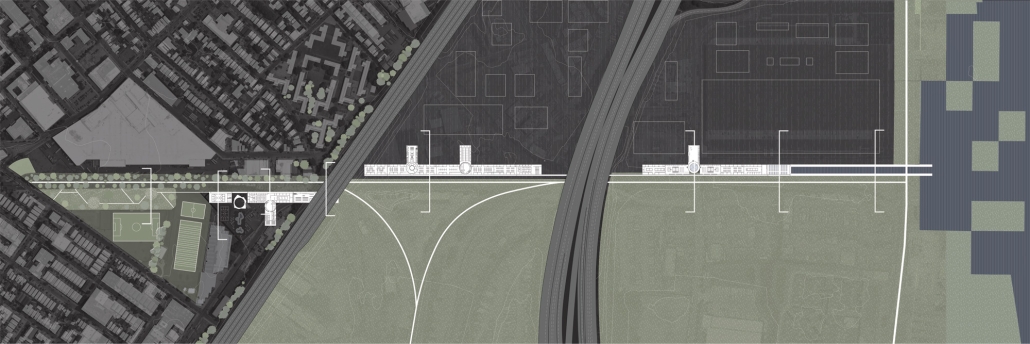

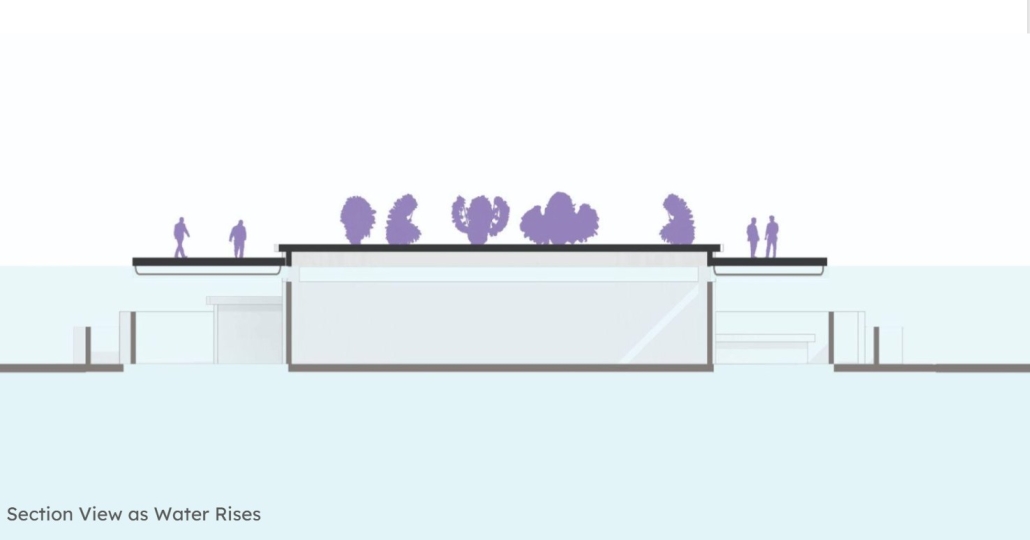

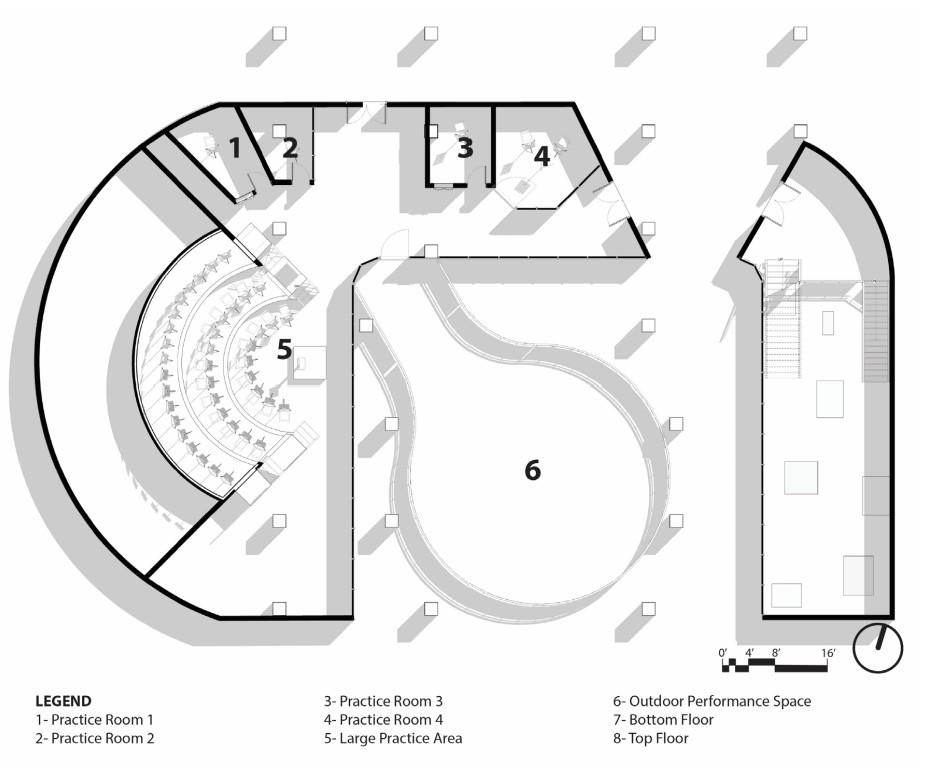

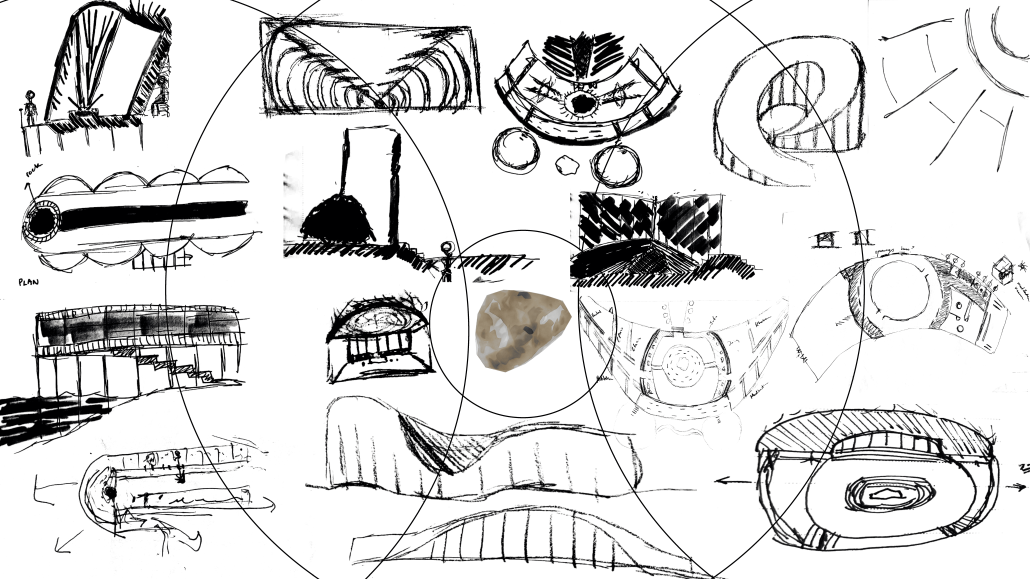

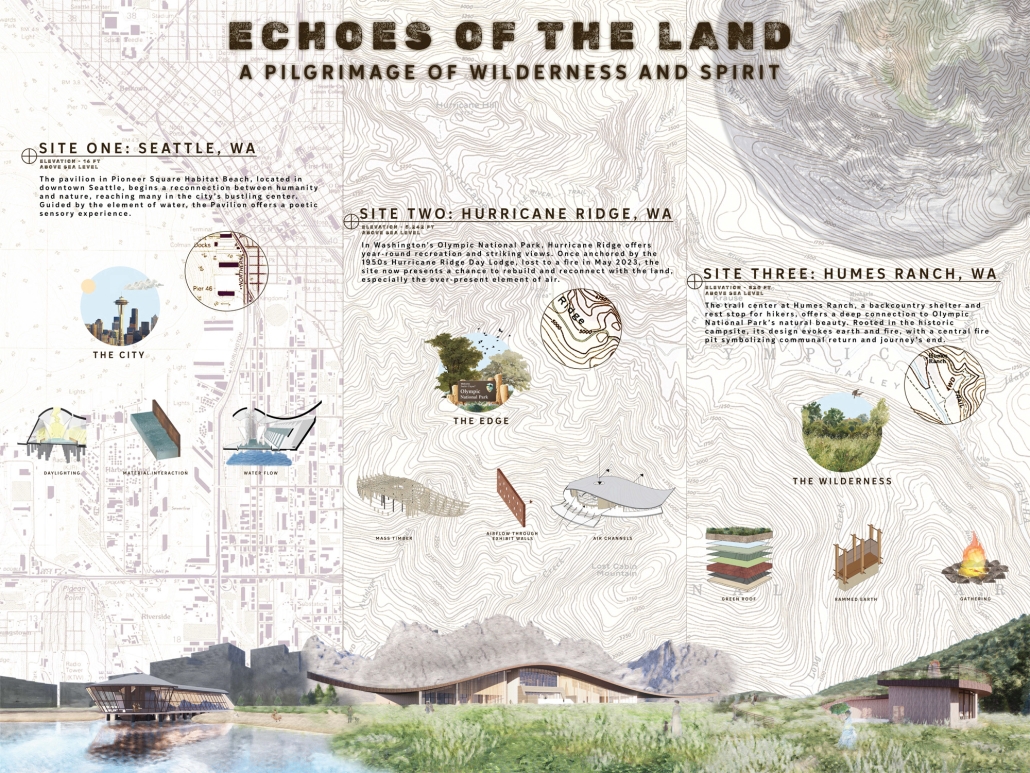

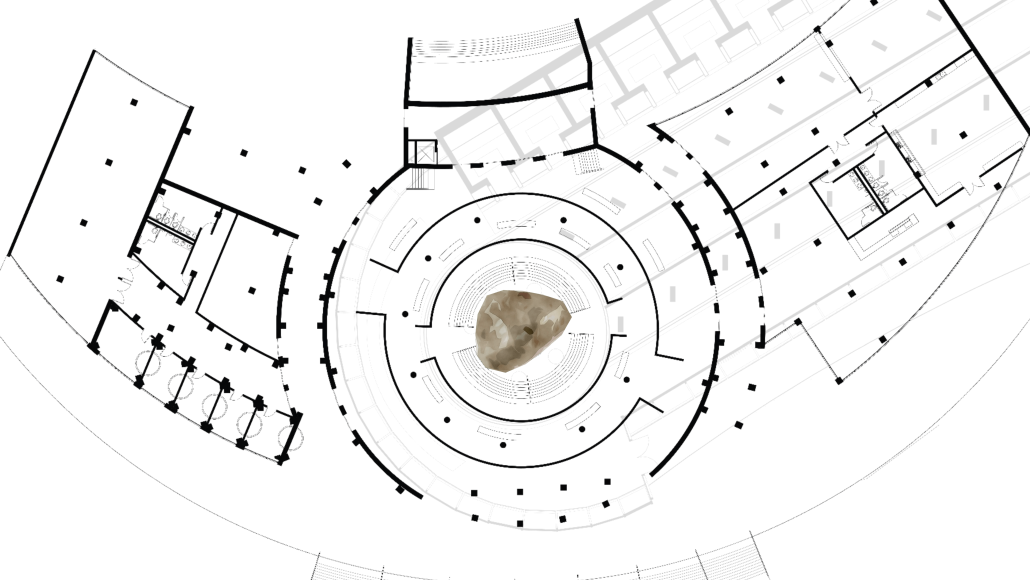

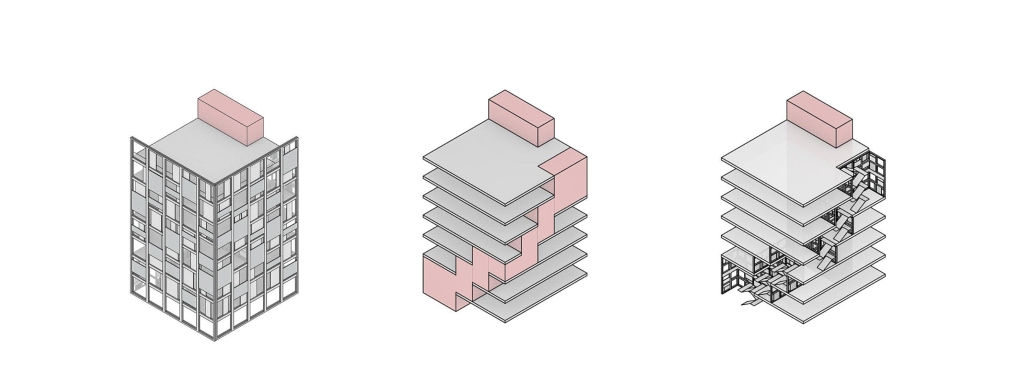

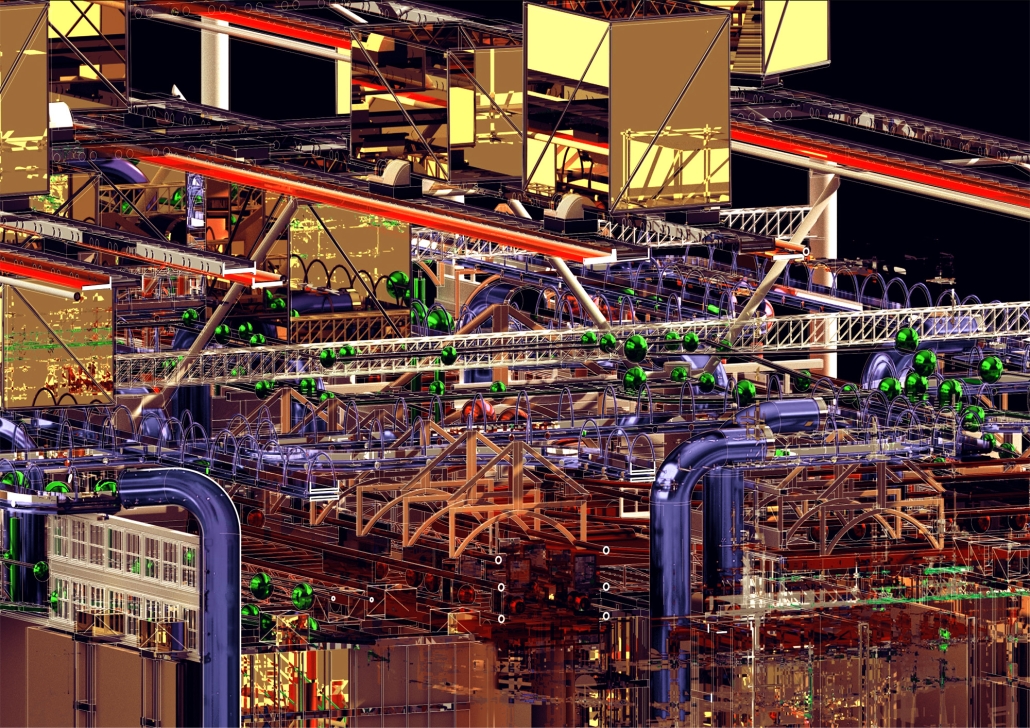

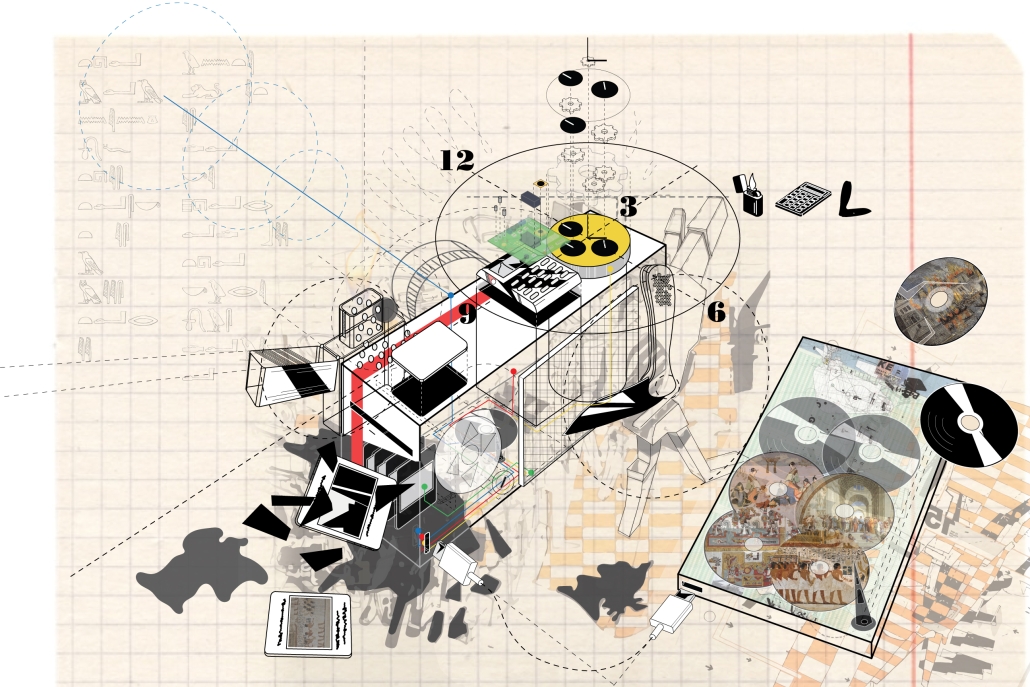

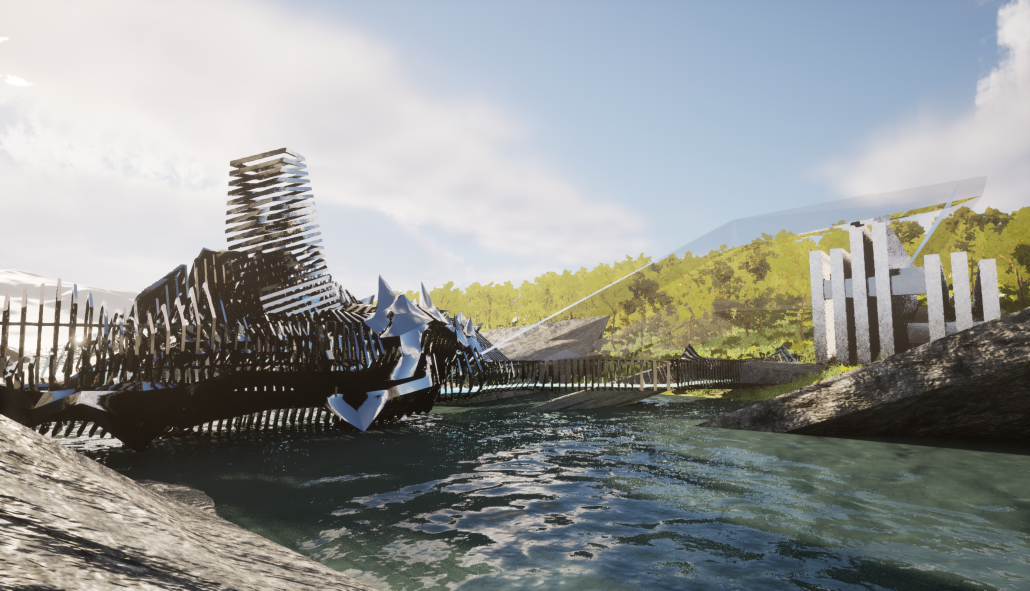

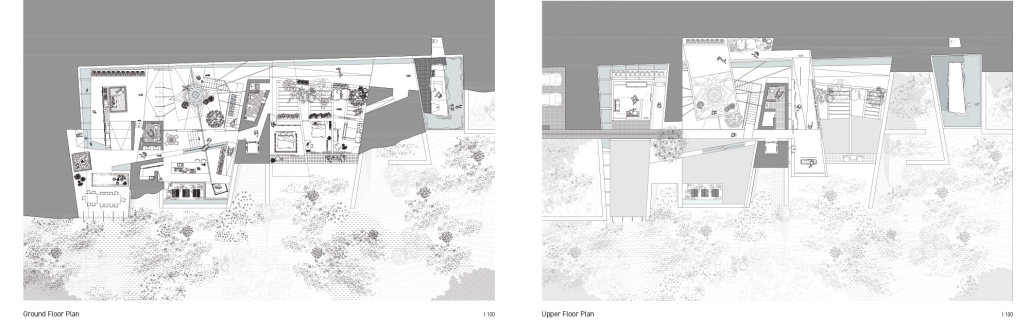

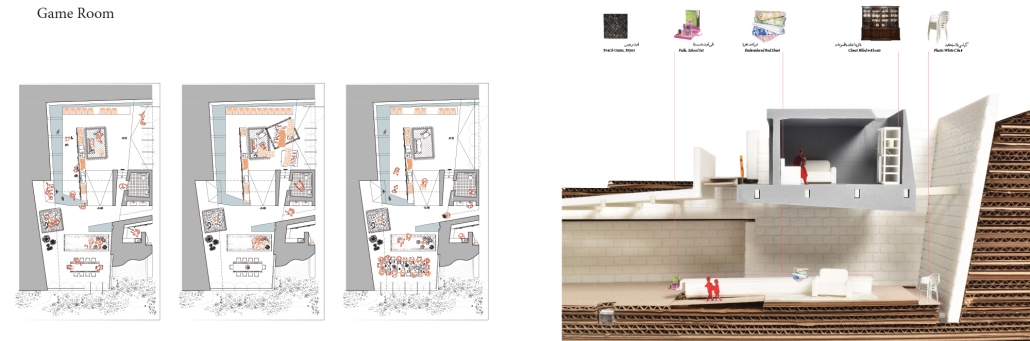

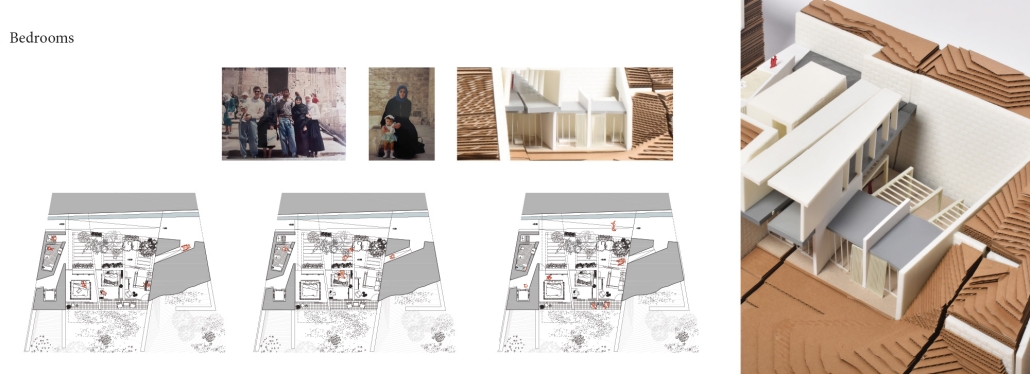

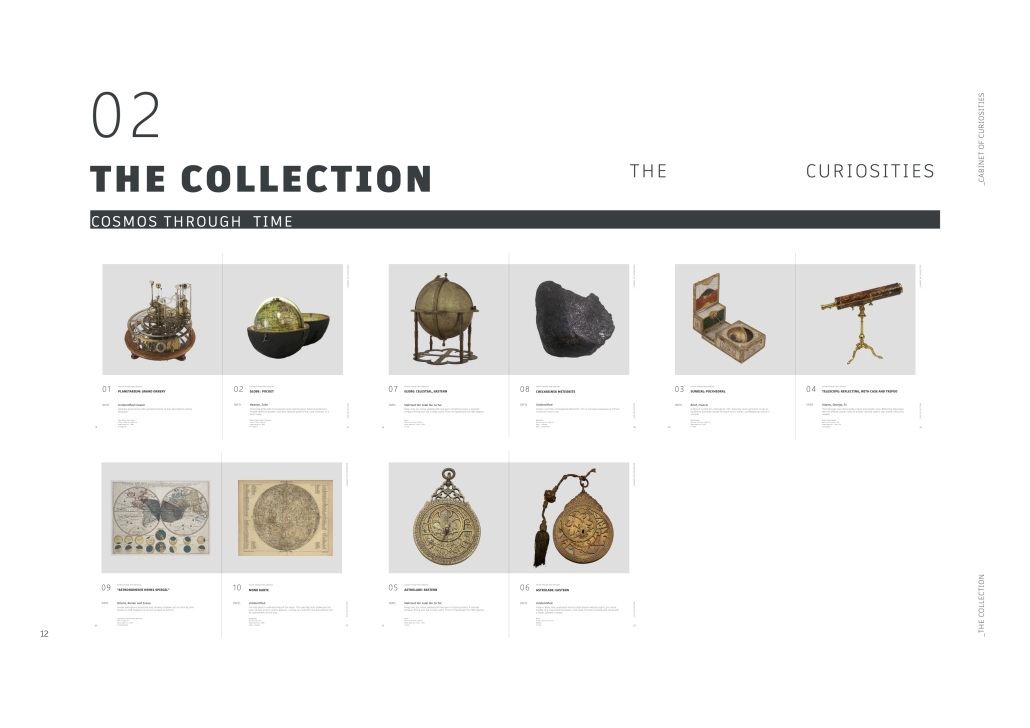

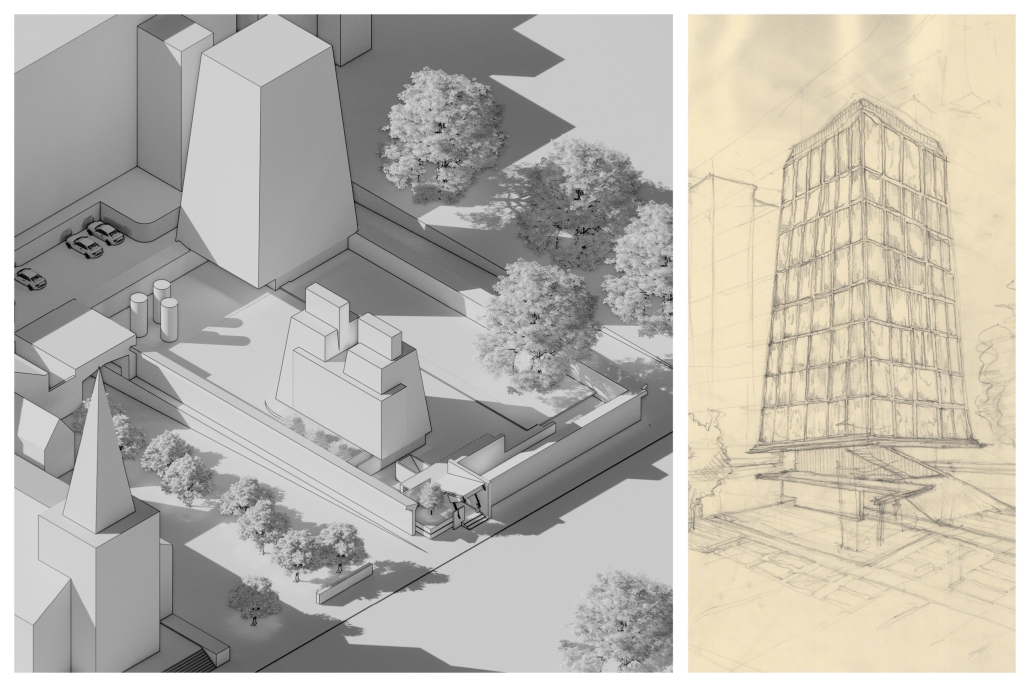

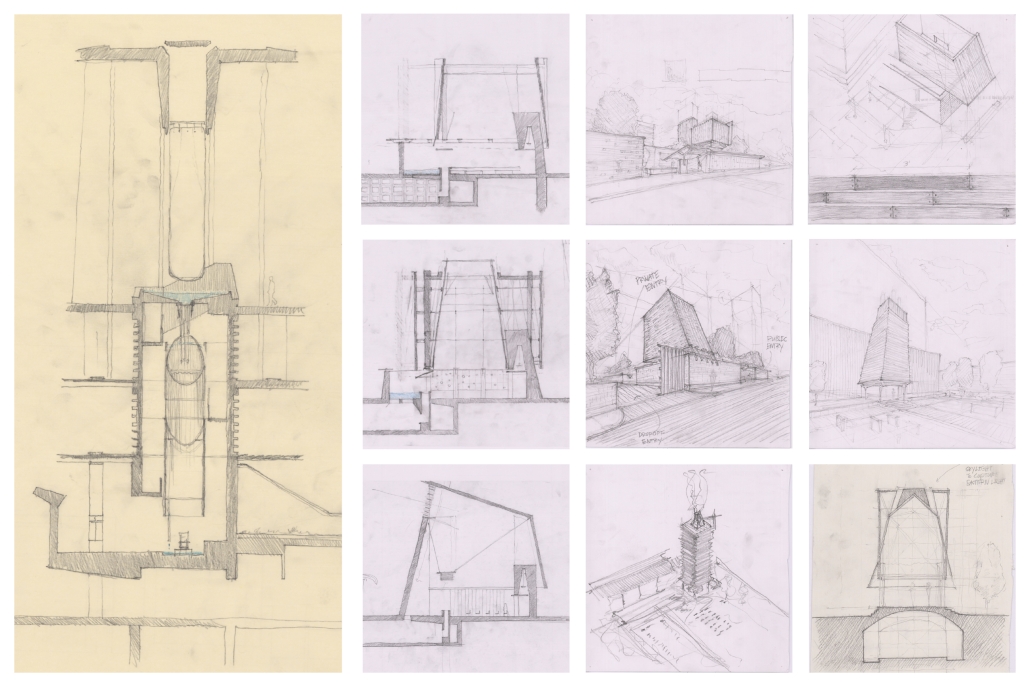

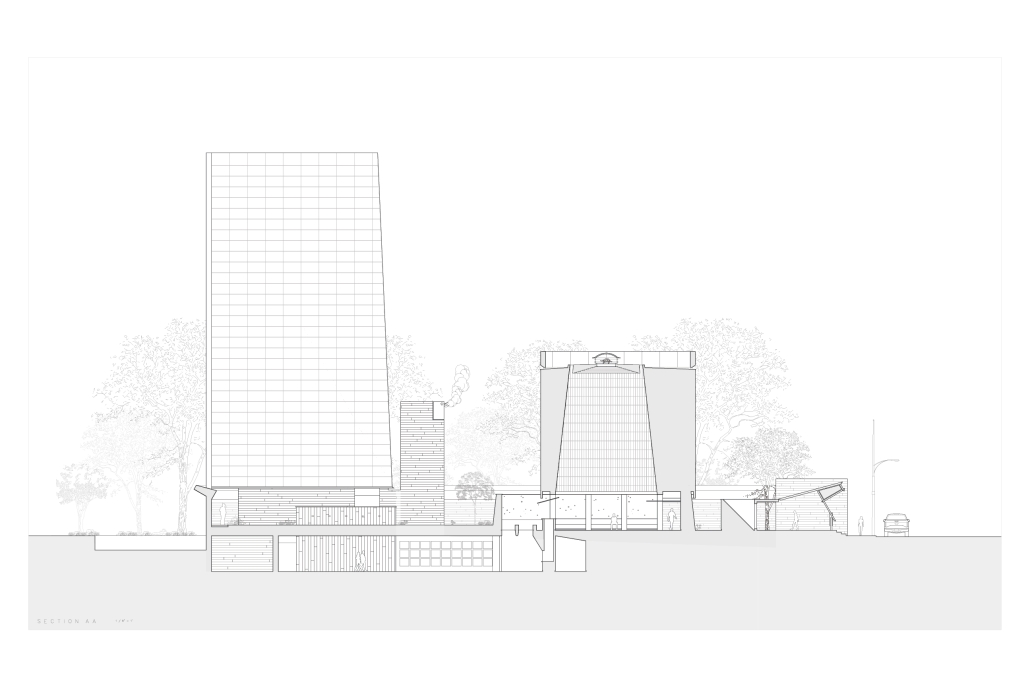

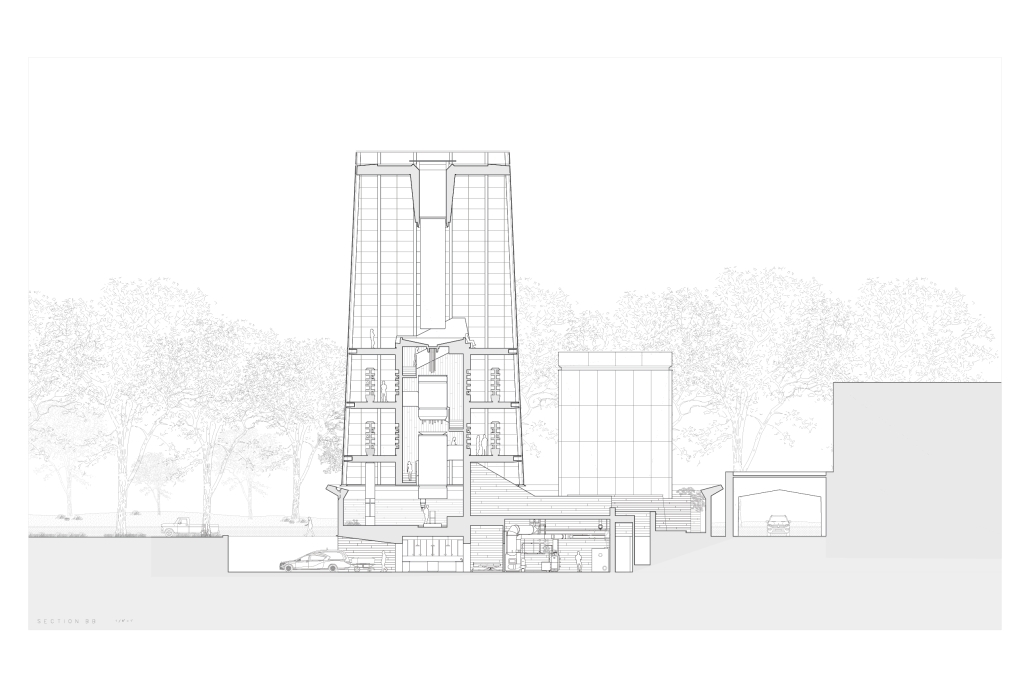

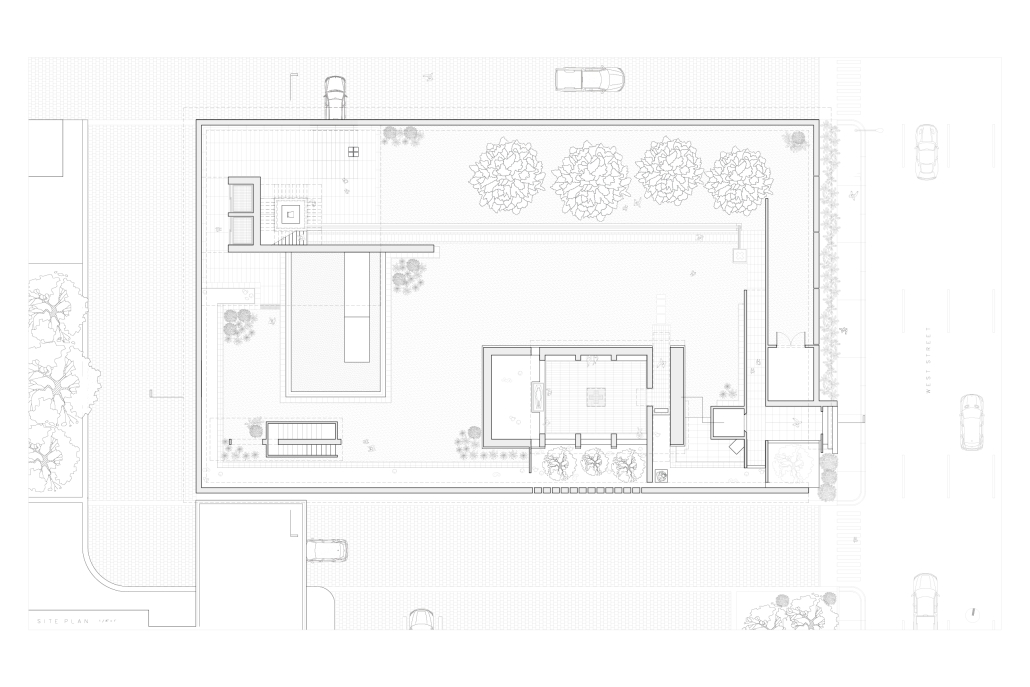

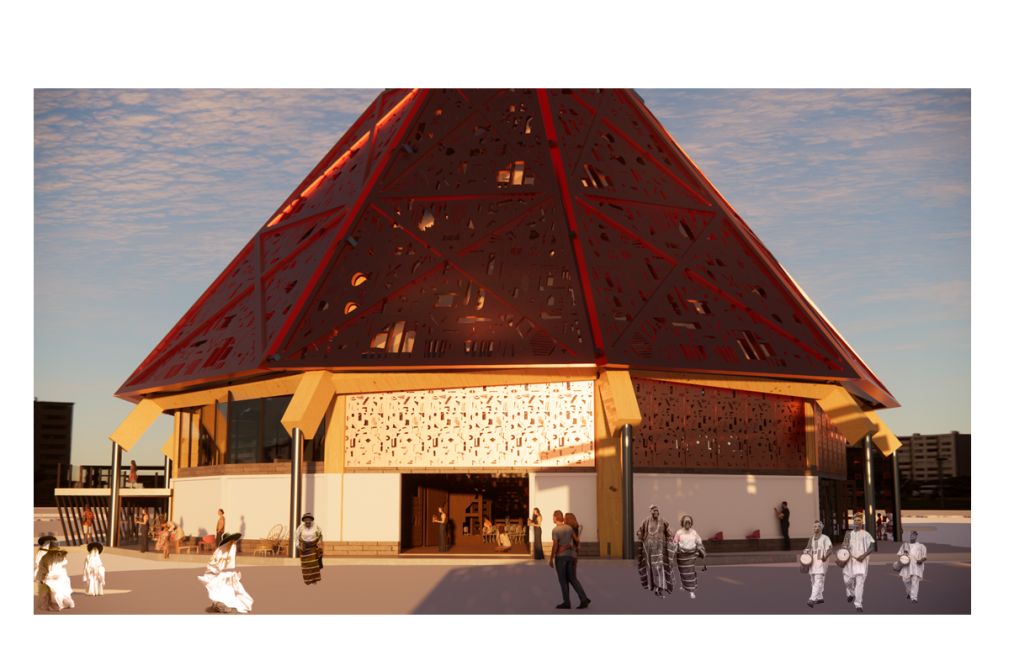

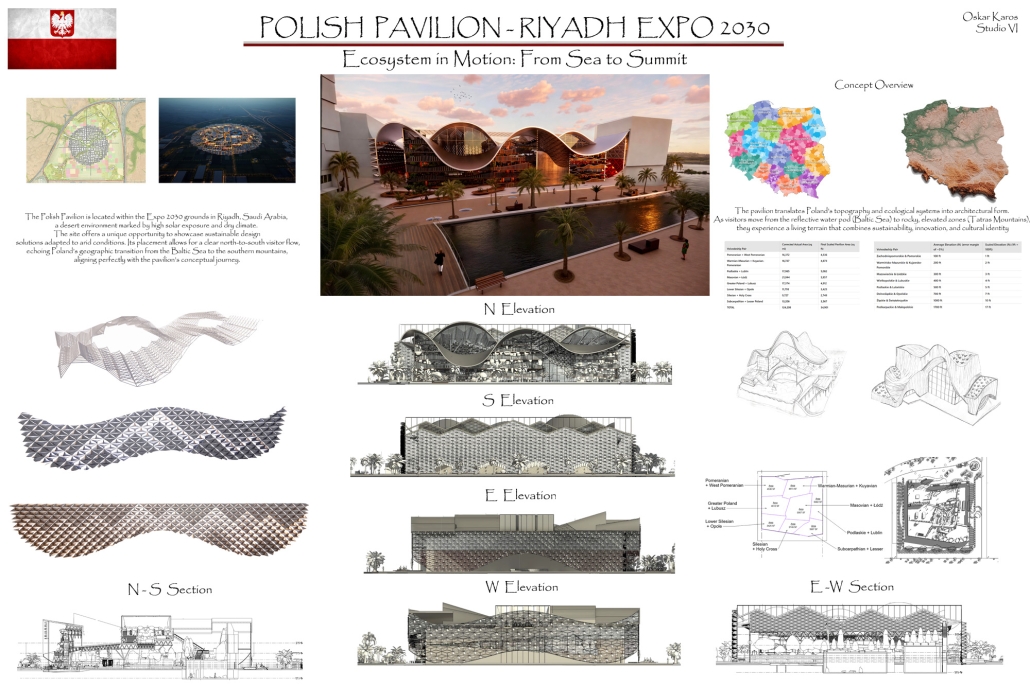

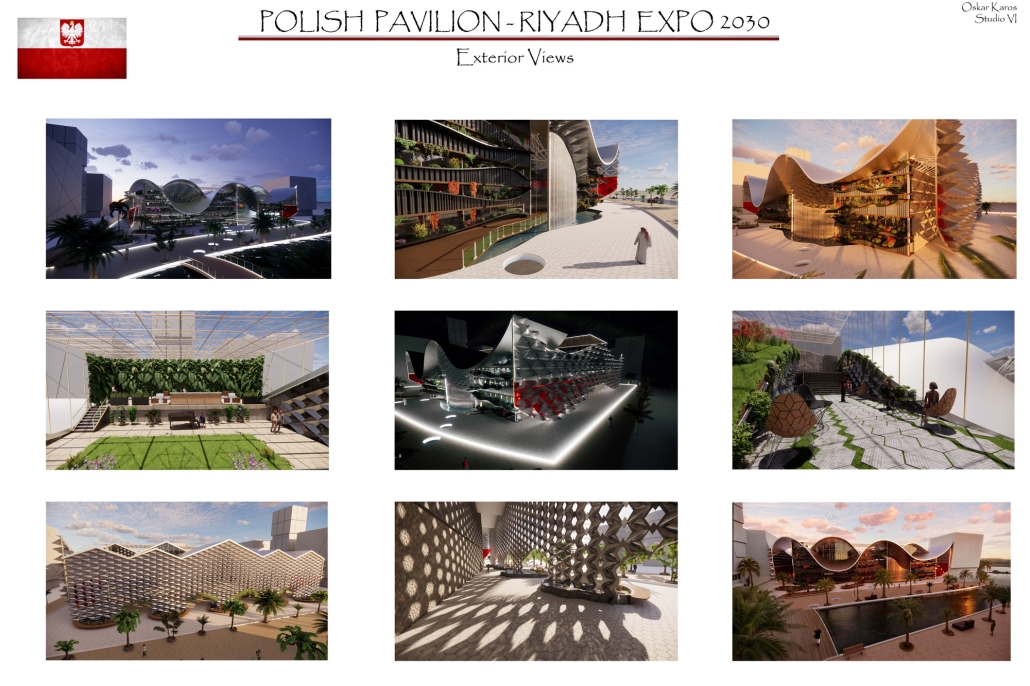

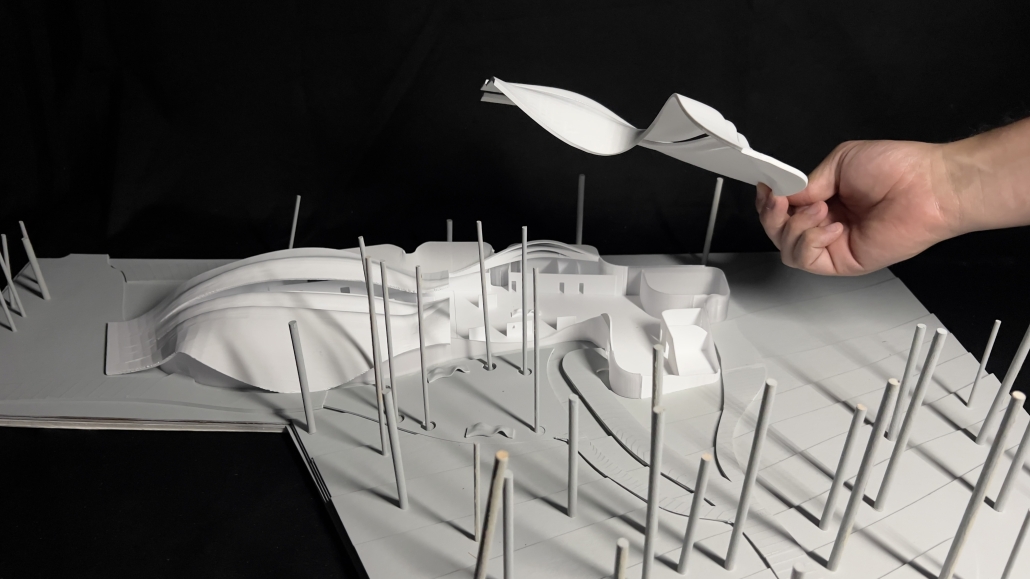

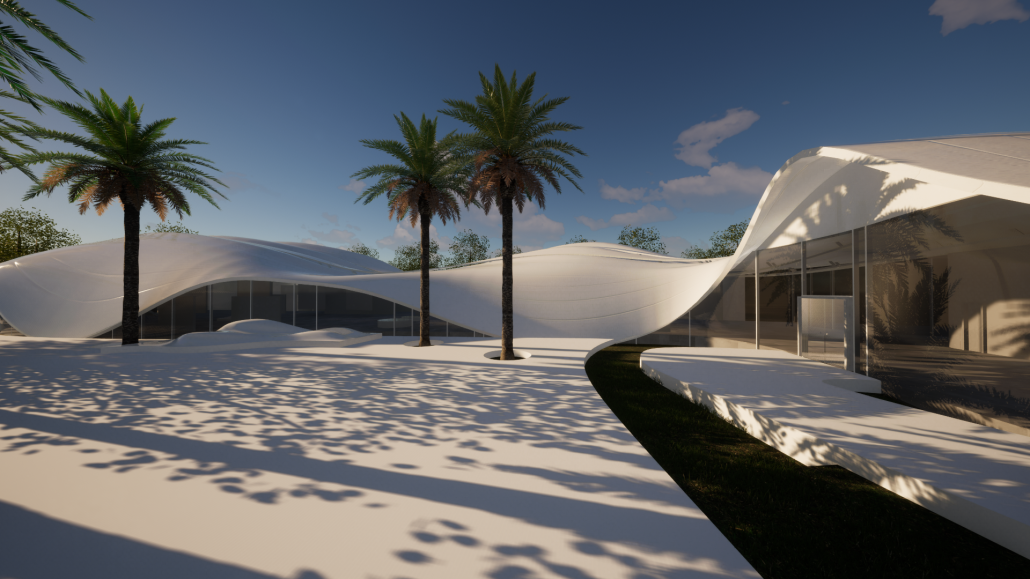

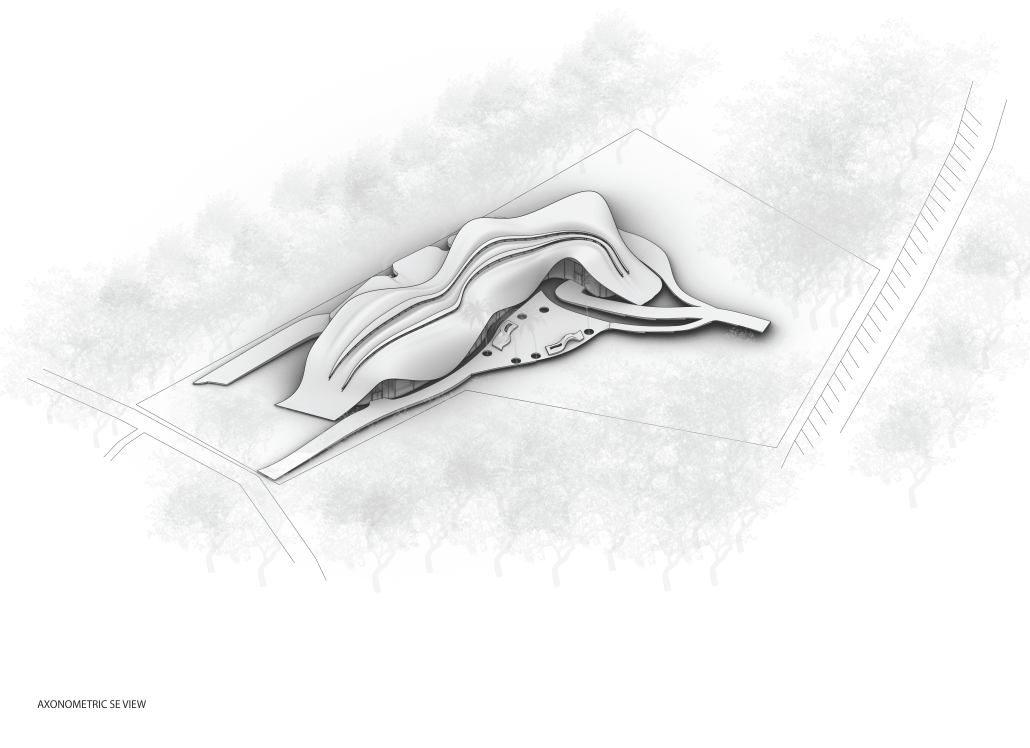

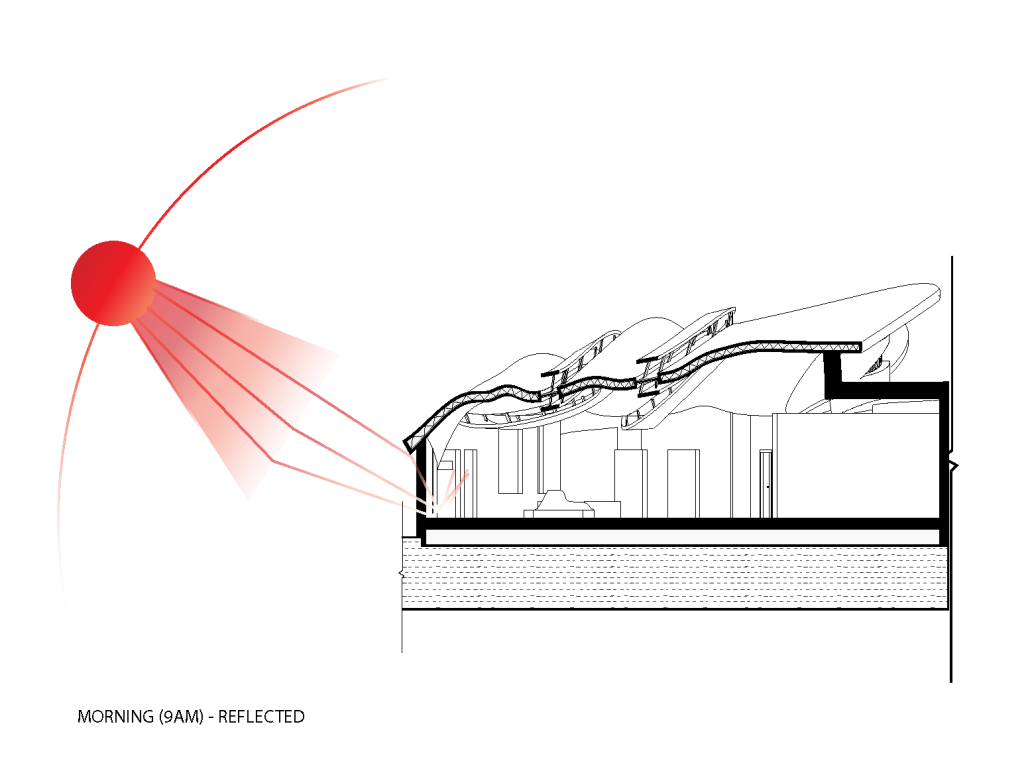

Share a Project You’re Proud of: I am most proud of my group project from our Collaborate studio, as alongside an interior design student and two other architecture students, we created a trauma-informed CTE (Career and Technical Education) campus for Lighthouse, a non-profit after-school program for middle school and high school students. The Lighthouse’s Trade and Industry Pathways Program nurtures the futures of local youth by fostering a sense of identity and belonging within its campus through opportunities for career and technical training, life skills development, and supportive social connection within a protected nature-centered community.

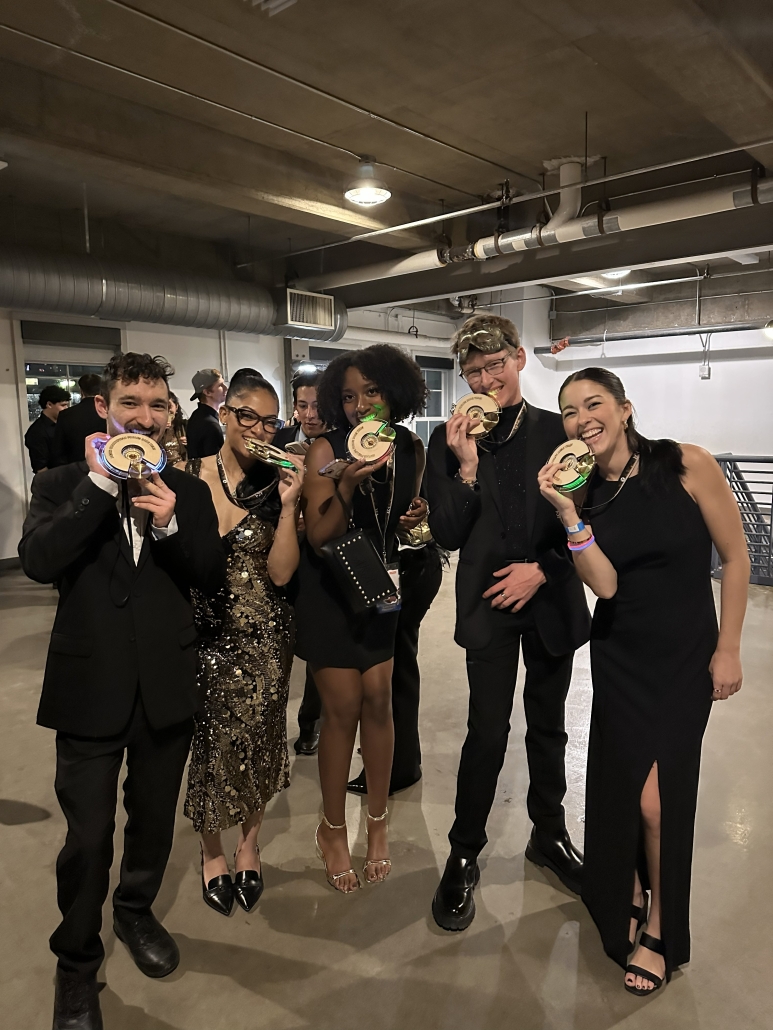

What Inspires You? I am inspired by the talent and passion of my peers, as their creativity is contagious and inspires me to collaboratively design in order to enhance the world and its populations. Engagement within a strong studio culture and robust architectural extracurriculars has inspired me to accomplish more than I ever thought possible, and I am forever grateful for the communities that have encouraged me throughout my academic journey.

What’s Your Student Superpower? My student superpower is never saying “no” to any opportunity or idea, as while it runs the risk of becoming over-committed, staying open-minded has allowed me to learn an incredible amount and greatly impact my communities. I encourage every single student to make the most of every single opportunity presented to them, as the wide range of experiences I have been honored to be a part of have greatly enhanced my education and imparted upon me valuable lessons on leadership, involvement, and service for my communities.

You can find Audrey on Instagram: @audreycherek

Interested in being featured? Email studyarchitecturedotcom@gmail.com for more details!