2023 Study Architecture Student Showcase - Part XVI

Welcome to Part XVI of the Study Architecture Student Showcase! Today, we explore the narrative of “othering” as it relates to architecture. The highlighted student work revisits norms by applying computational methodologies to the design process, positioning a tent city in an industrial zone, reimagining modernization without demanding the complete erasure of urban communities, and more. Read on for more information.

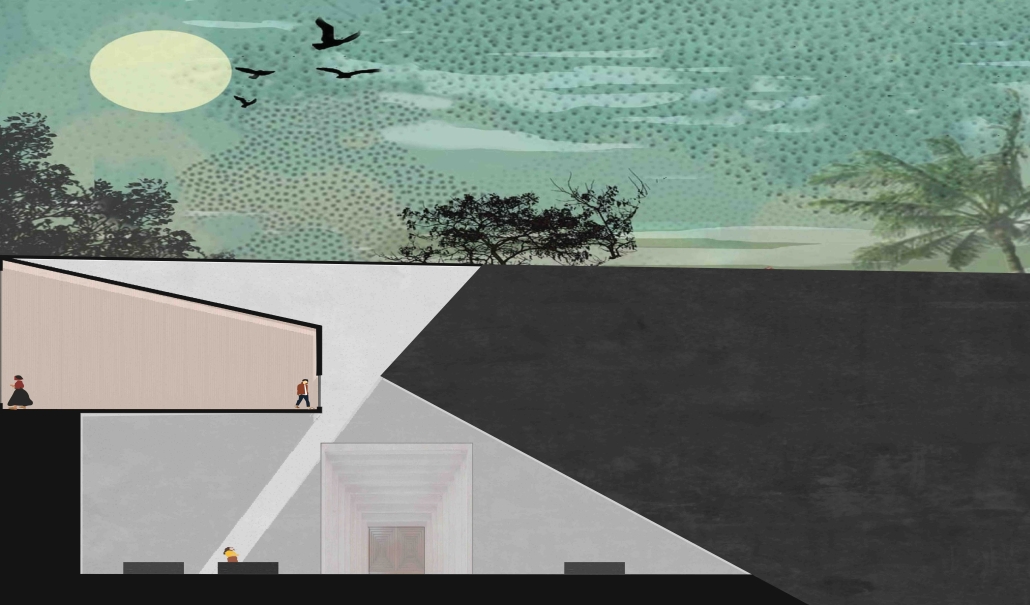

Alleviating Othering Spaces, AI Analysis, and Form in Negril, Jamaica by Caelyn Ford, Bachelor of Science in Architecture ‘23

Boston Architectural College | Advisor: Robert C. Anderson

Nothing will change until we acknowledge two truths about ourselves and the built environment; that architecture reflects, reaffirms, and legitimizes narratives of a society that ‘others’ and defines an individual’s role in society, begetting ‘othering spaces.’

That which can be physically confirmed is often prioritized over its cognitive counterpart. Design solely for the corporeal, neglecting the cognitive, is a lie of pretended humanism within the architecture profession. The thesis aims to develop a tool that expands the

capabilities of inclusive design to transform perceptual understandings of the self and ‘other’ by analyzing architecture through a neuro-phenomenological lens. This endeavor is two-fold: design for the mind and design for the other.

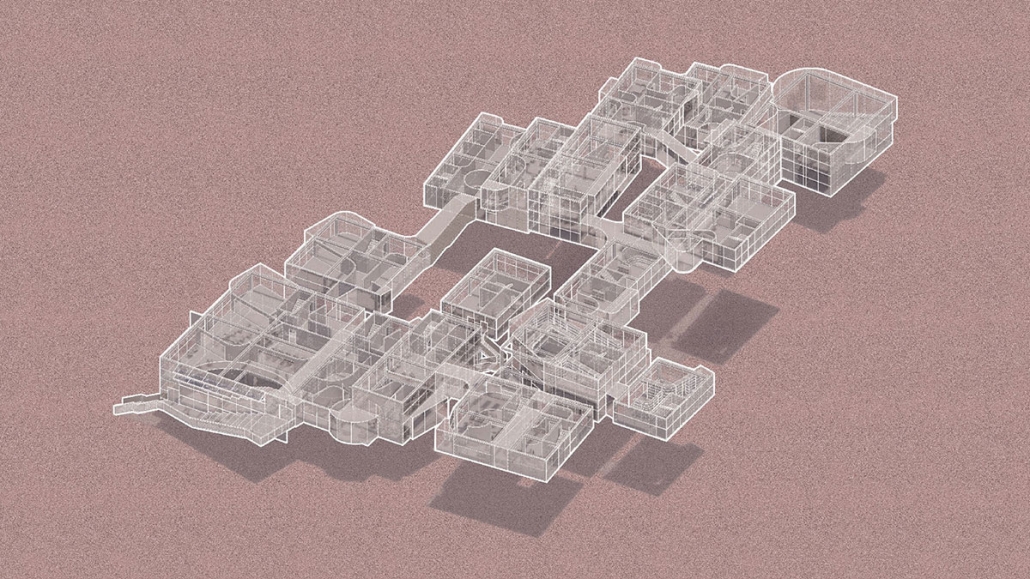

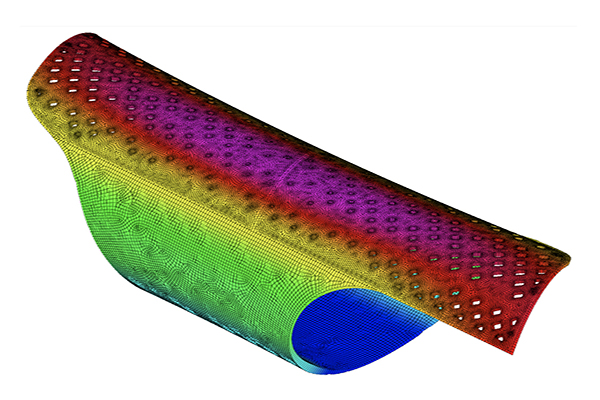

The thesis project investigates means of alleviating ‘spatial othering’ by quantitatively studying the building’s behavioral and emotional effect on its users to equalize the cognitive experience. Cognitive-Informed Design in architecture presents an opportunity to create paradigm shifts by applying computational methodologies to the design process. Recognizing the need for a system to connect with the end users efficiently during the design process, the potential of web-based VR, AI-generated eye tracking, brain mapping software, and biosensors was explored in this thesis to develop the design criteria.

This project was selected as the Best of Bachelor of Science degree project.

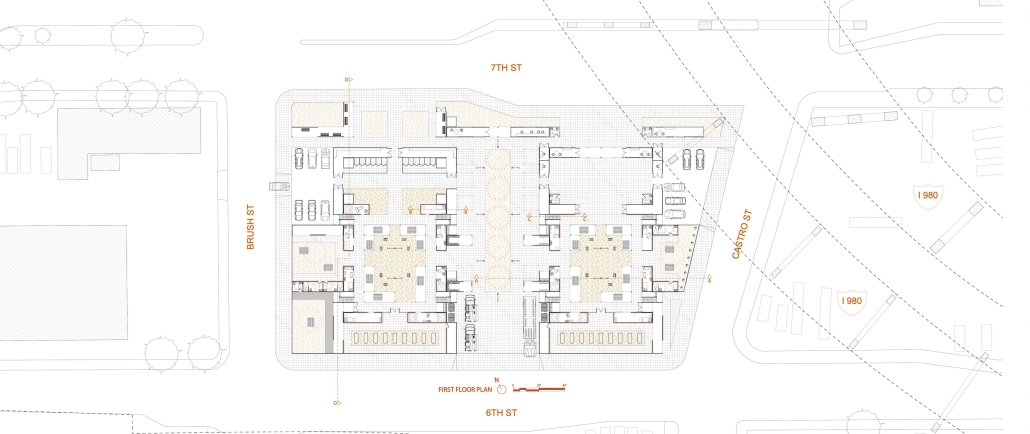

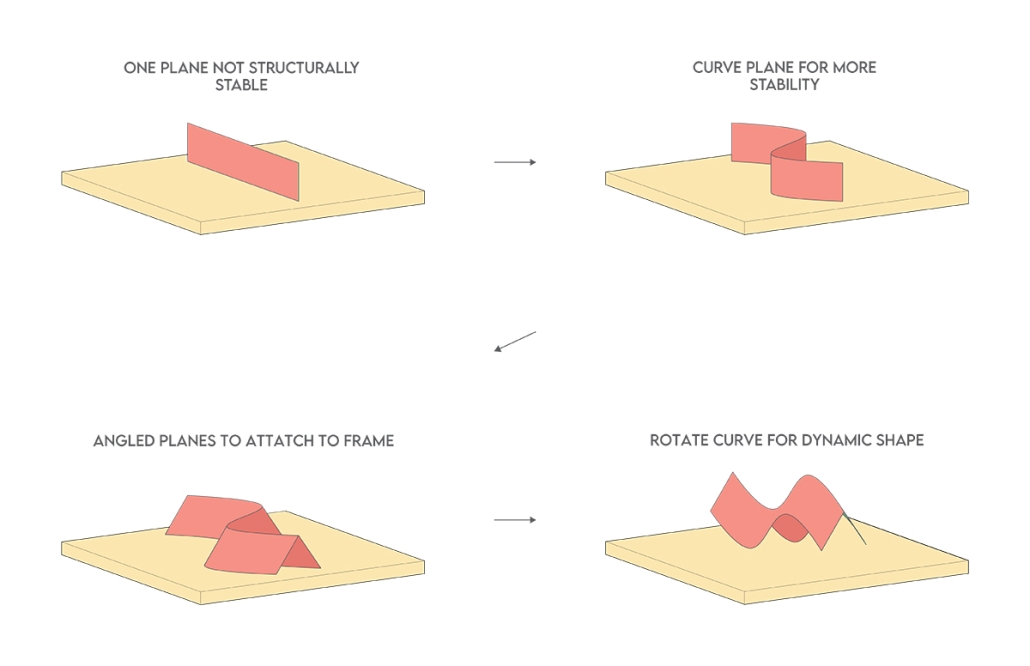

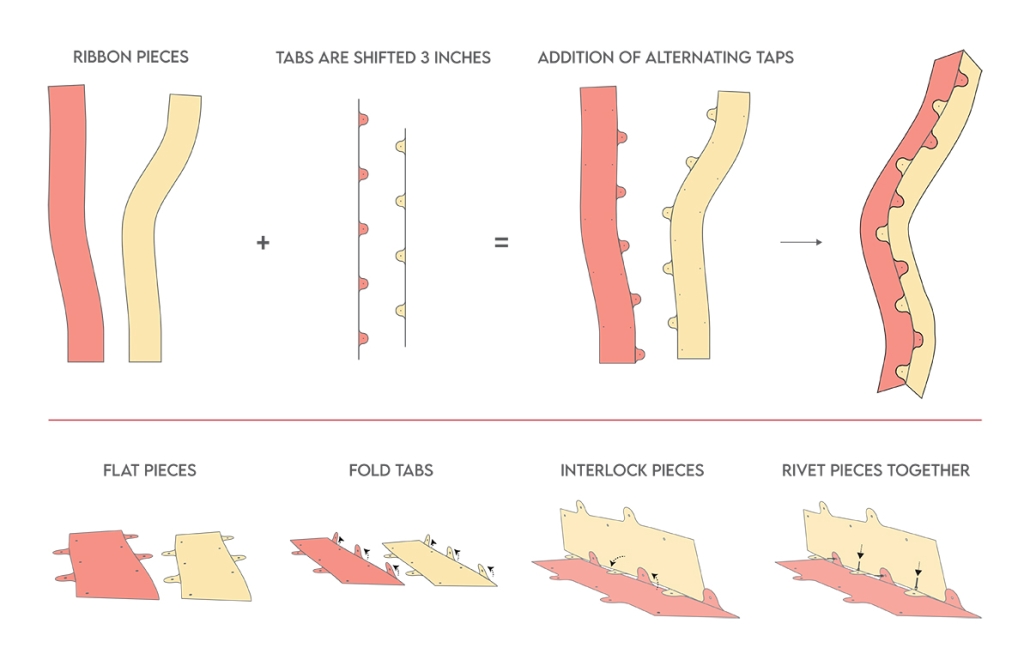

Urban Refuge: Assisting in the Development of Tent Communities Through Modular and Trauma Sensitive Design by Peter Hope, M. Arch ‘23

Academy of Art University School of Architecture | Advisor: Eric Reeder

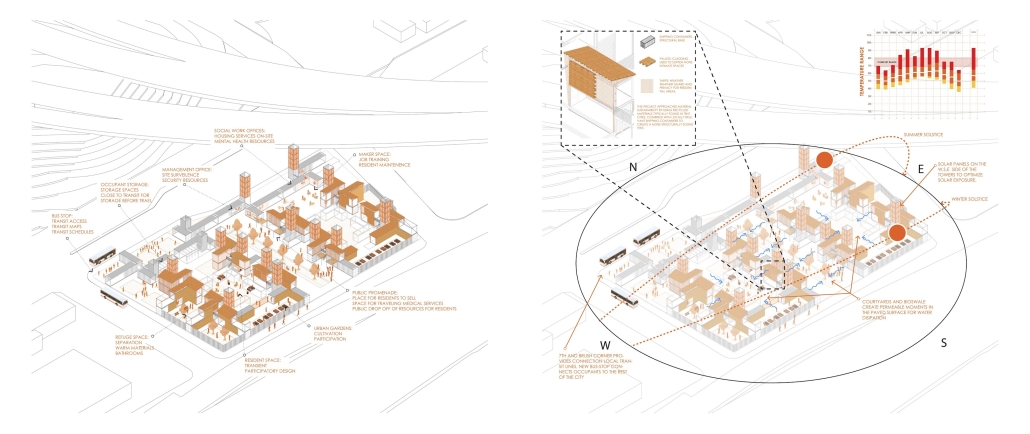

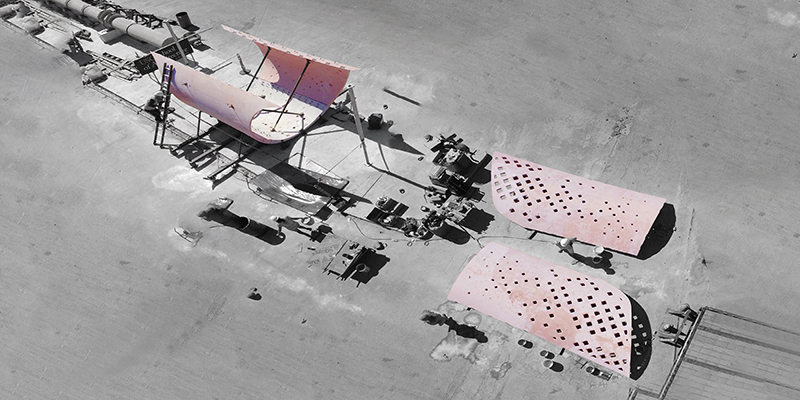

Homelessness in the United States is a problem that disproportionately affects California. According to the World Population Review, the homeless population in California is 161.5 thousand; that is 16x more homeless people than the national average of 11.4 thousand. It is suffice to say that the issue of homelessness is not going away any time soon. Of all the cities in the United States, three of the cities with the highest homeless population exist in the Bay Area. San Jose, Oakland, and San Francisco account for 10% of the homeless population of the entire state.

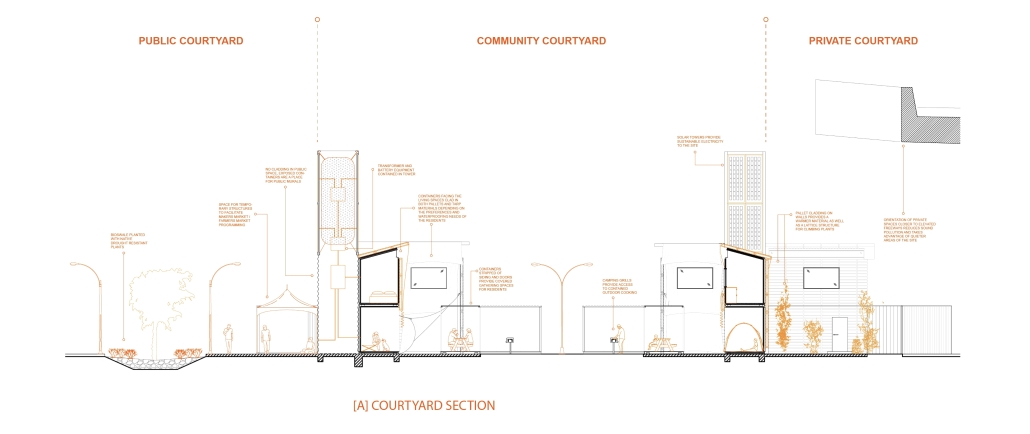

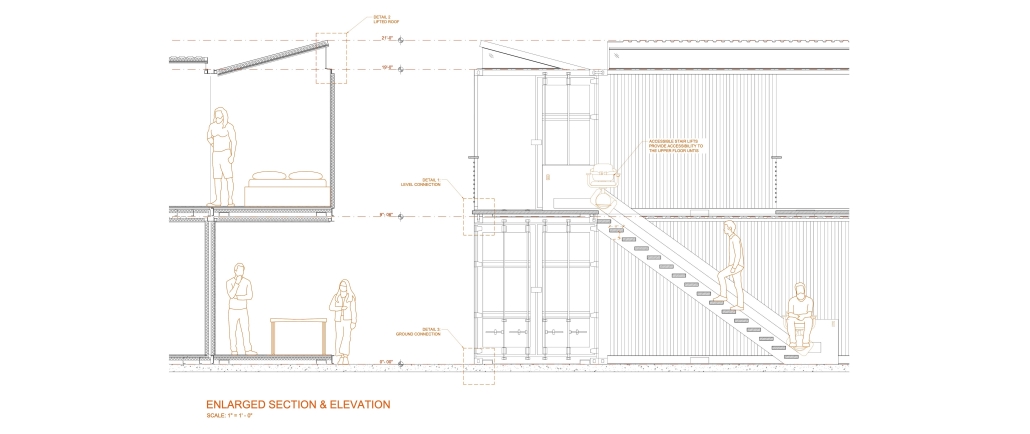

The objective of this thesis is to find ways to create better spaces of refuge for the unhoused residents of Oakland, who currently call tent cities home. Tent cities are one way that the unhoused communities organize themselves. Tent cities can pop up anywhere, from highway medians to the side of the road. The selected site for this project is inhabited by a fledgling tent city that has not quite found an organizational rhythm as others in Oakland have. It is also positioned in an industrial zone which presents opportunities for city sanctioning, should the project be successful.

Instagram: @ericreeder.architect, @_peterhope

Kalunitas by Alex Jauregui, Alex Lopez, Armando Torres, Ayah Milbes, Bailey Campbell, Chris Rosenbaum, Francisco Ramos, Hannah Gonzalez, Huda Shahid, Joshua Arriaga, Josue Garay, Justin Mai, Kavi Patel, Lucio Castro, Macey Mendoza, Sarah Trevino, Sophia Cruz, Valentin Torres, and Xavier Zamora, B.Arch ‘23

University of Texas at San Antonio | Advisor: Armando Araiza

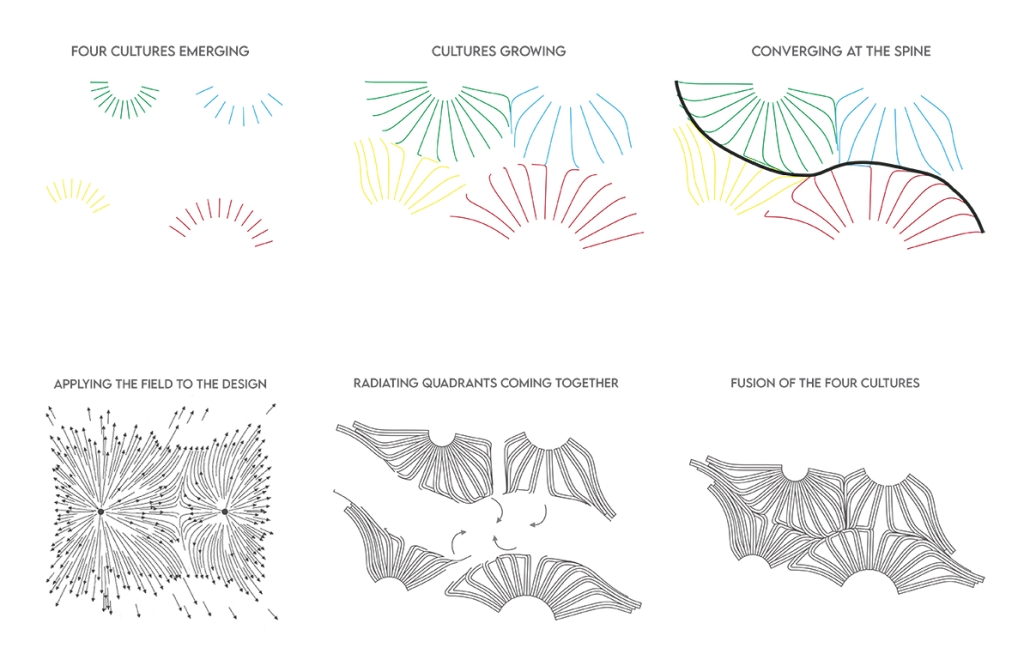

An installation that illustrates the movement of people to San Antonio throughout the past 300 years and beyond. The word “kal” derives from the indigenous language of the Coahuiltecans meaning “come together” and “unitas” being the Latin word for “unity.” Kalunitas expresses the convergence between four of the founding cultures that have made the San Antonio region one of the most diverse in the United States.

Instagram: @conetic_studio

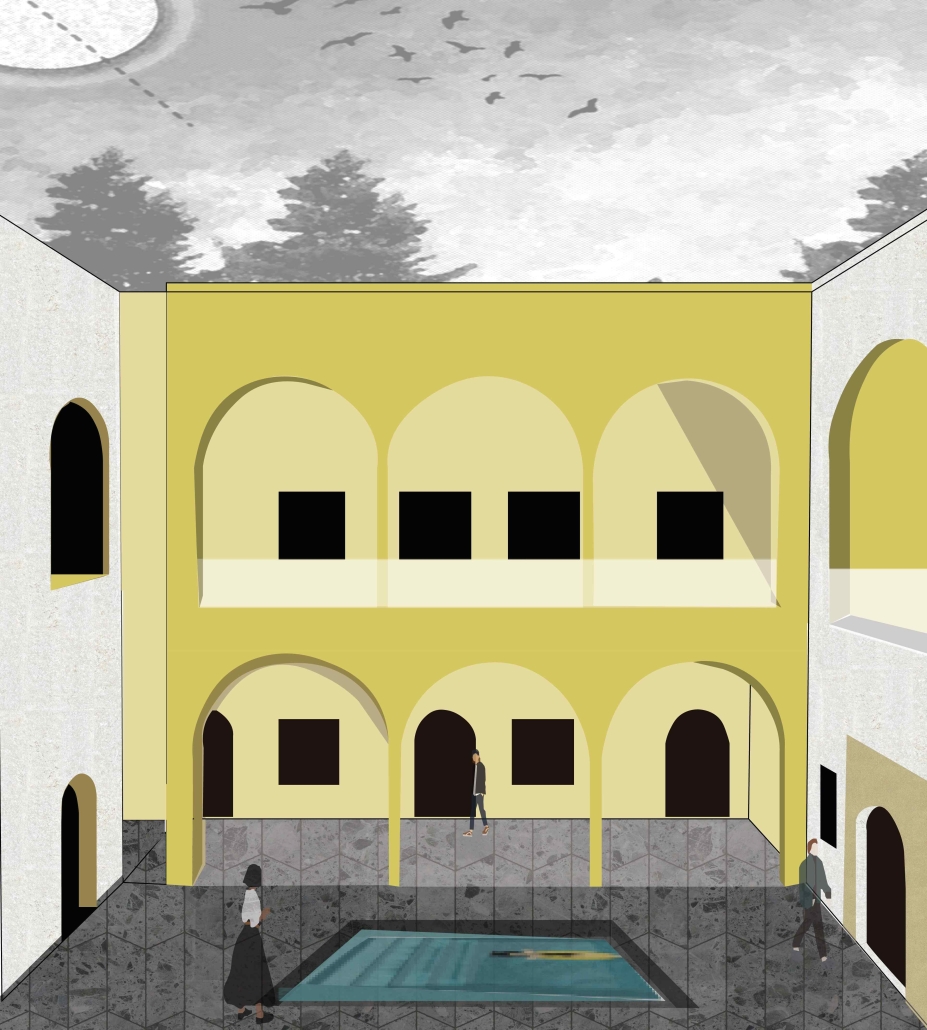

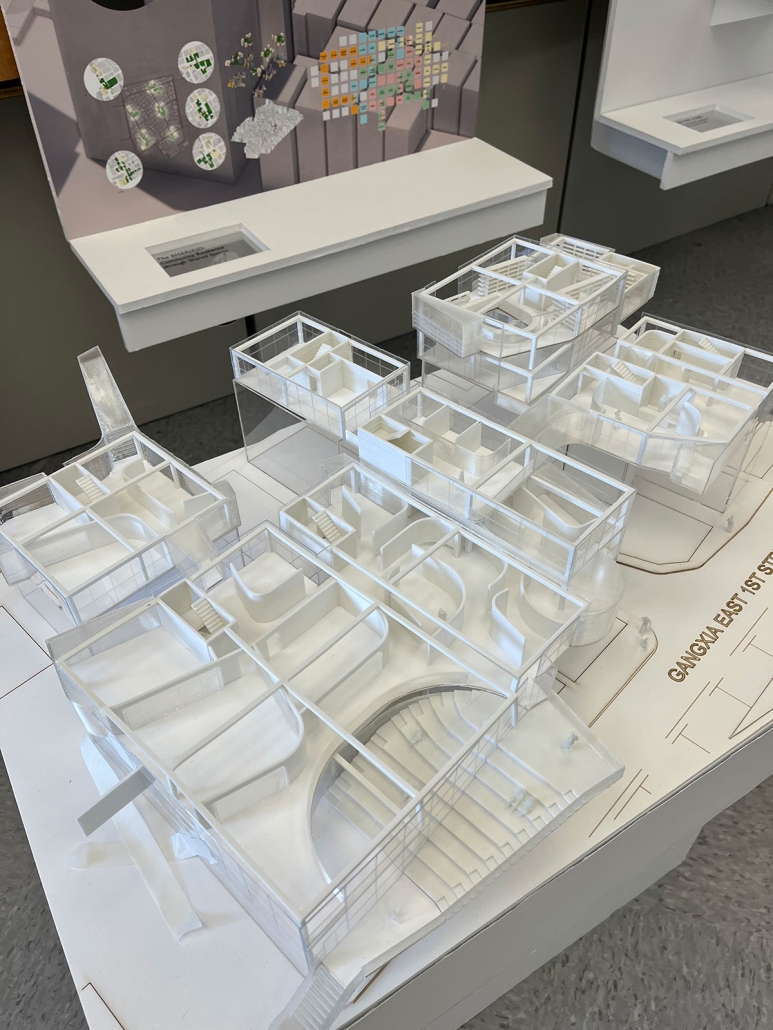

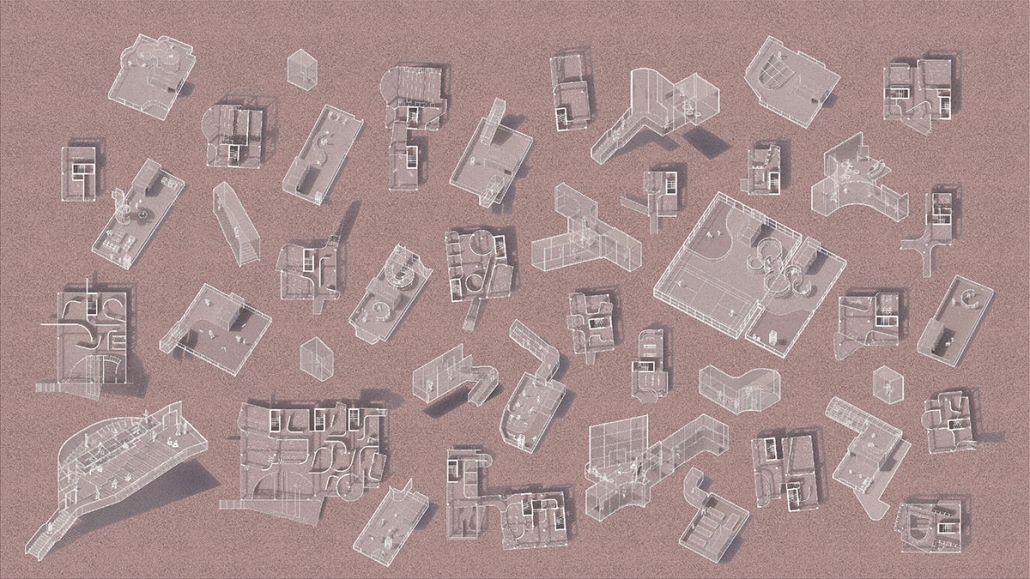

The Shar(e)d: Community Resilience Through Shared Spaces by Yiting Chen, M.Arch ‘23

University of Southern California | Advisor: Amy Murphy

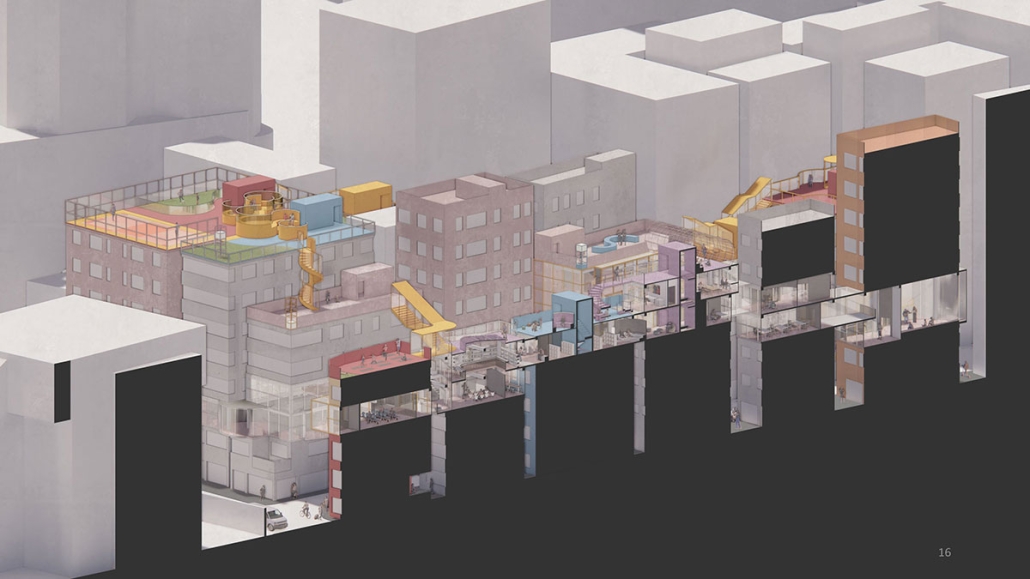

Cities’ growth and evolution can pressure existing communities by changing the urban landscape, as seen in the Shard in London, where the construction of a glass skyscraper risks displacing the economically poor and working class. Such development doesn’t necessarily bring true social progress to the neighborhoods. A large area of glass introduced in the neighborhood almost put a death sentence on the community. This trend can be observed in many communities near central business districts.

Is there another way towards modernization without demanding complete erasure?

How can the elements of the Shard be recombined into the urban landscape in a more sensitive gesture?

How can the use of glass be more about the place and the people?

This project focuses on the development of public and shared spaces in GangxiaVillage. The synergy of public spaces can be infused into this super-dense neighborhood to ensure that the benefits of progress and development are shared fairly.

The glass will bring active changes and connections while preserving the special urban fabrics and characters of the neighborhood. A network and system of resources will be introduced to serve the residents, and this network is expected to expand and evolve when future needs arise.

This project received the USC Master of Architecture Distinction in Directed Design Research.

Instagram: @sallychenyt, @amy_murphy143

See you next week for the next installment of the Student Showcase!