2023 Study Architecture Student Showcase - Part XXV

Biomaterials are the central theme of the projects featured in Part XXV of the Study Architecture Student Showcase. From BioRock to mushrooms and mycelium, the showcased work goes beyond the traditional uses of biomaterials to propose alternatives that offer symbiotic outcomes by simultaneously solving architectural challenges and promoting sustainability.

Toronto’s Terrestrial Reefs by Cameron Penney, M.Arch ‘23

Carleton University | Advisor: Lisa Moffitt

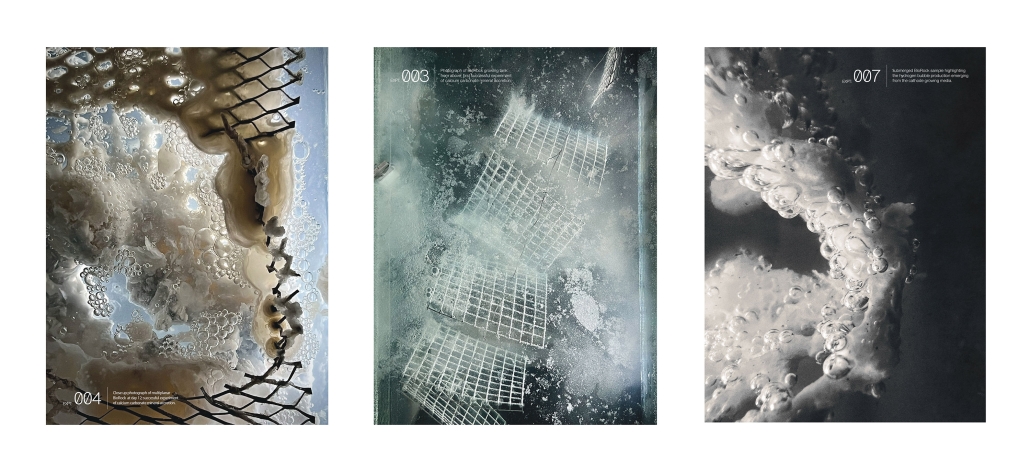

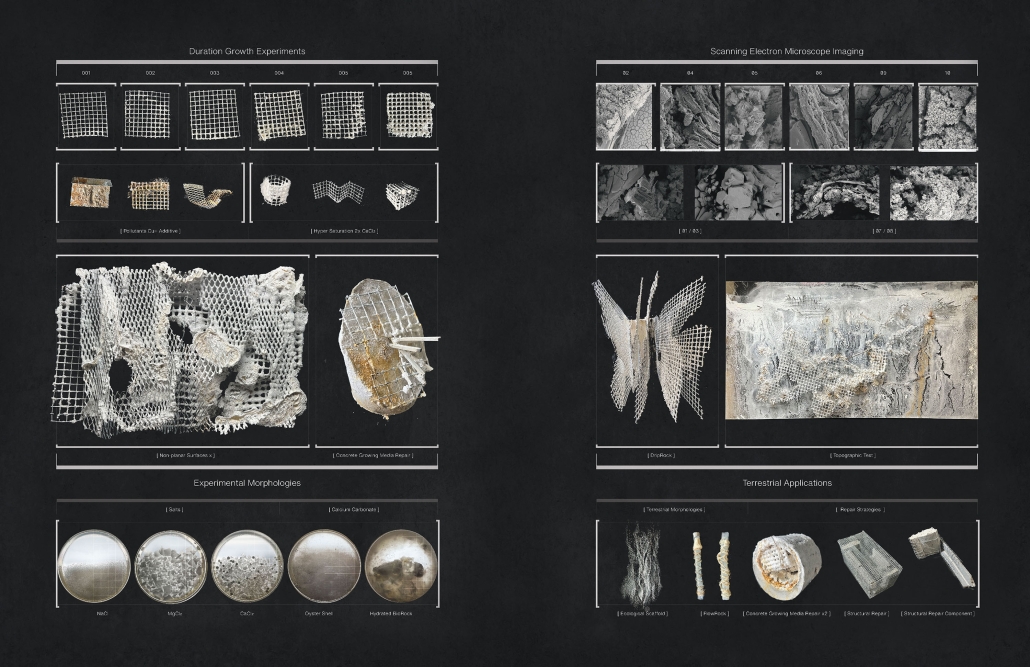

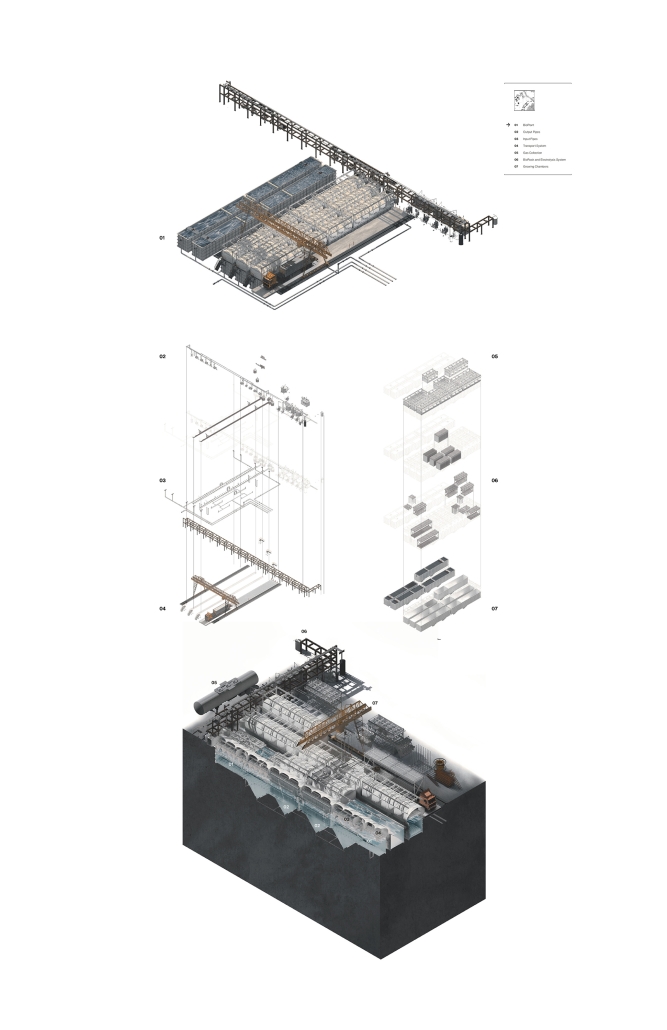

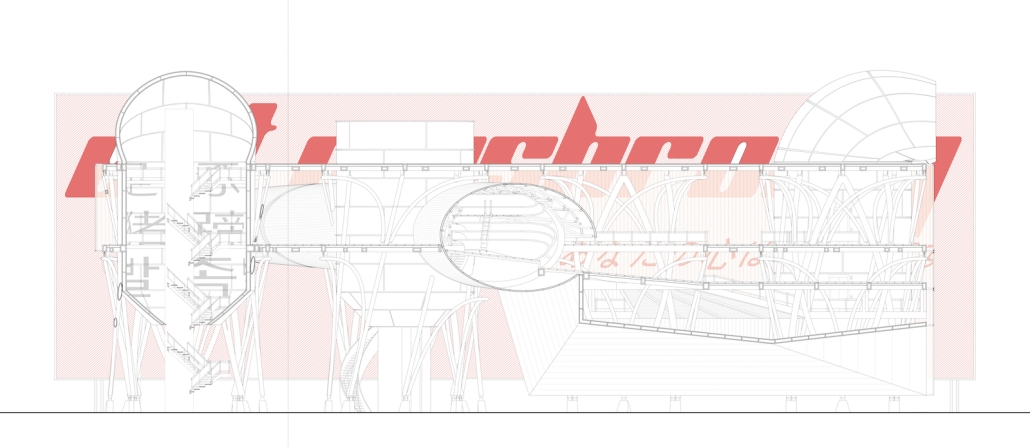

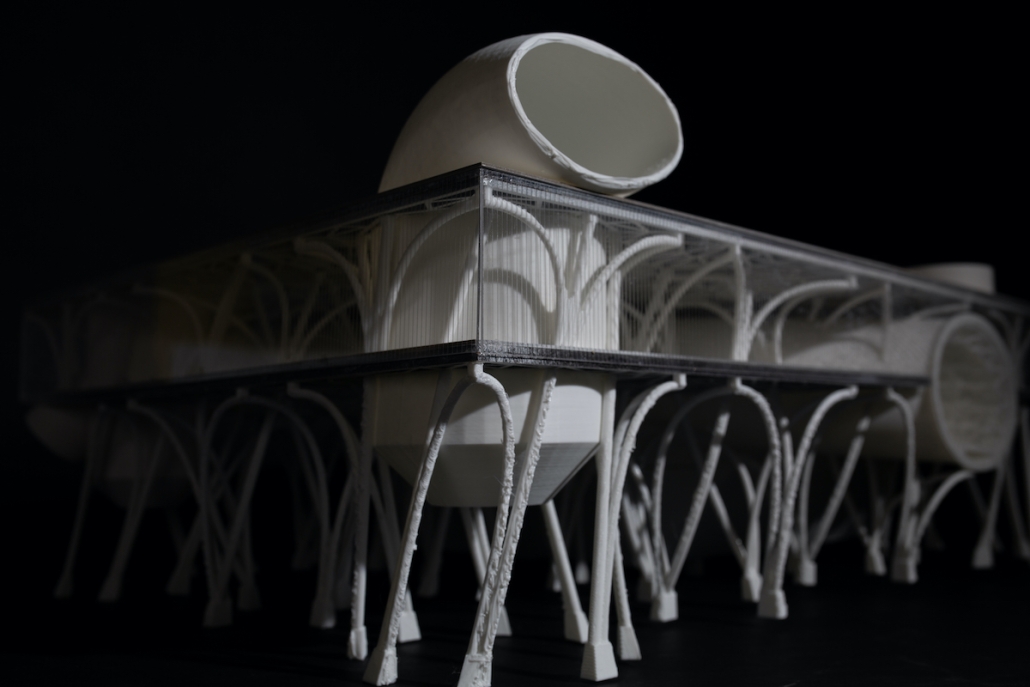

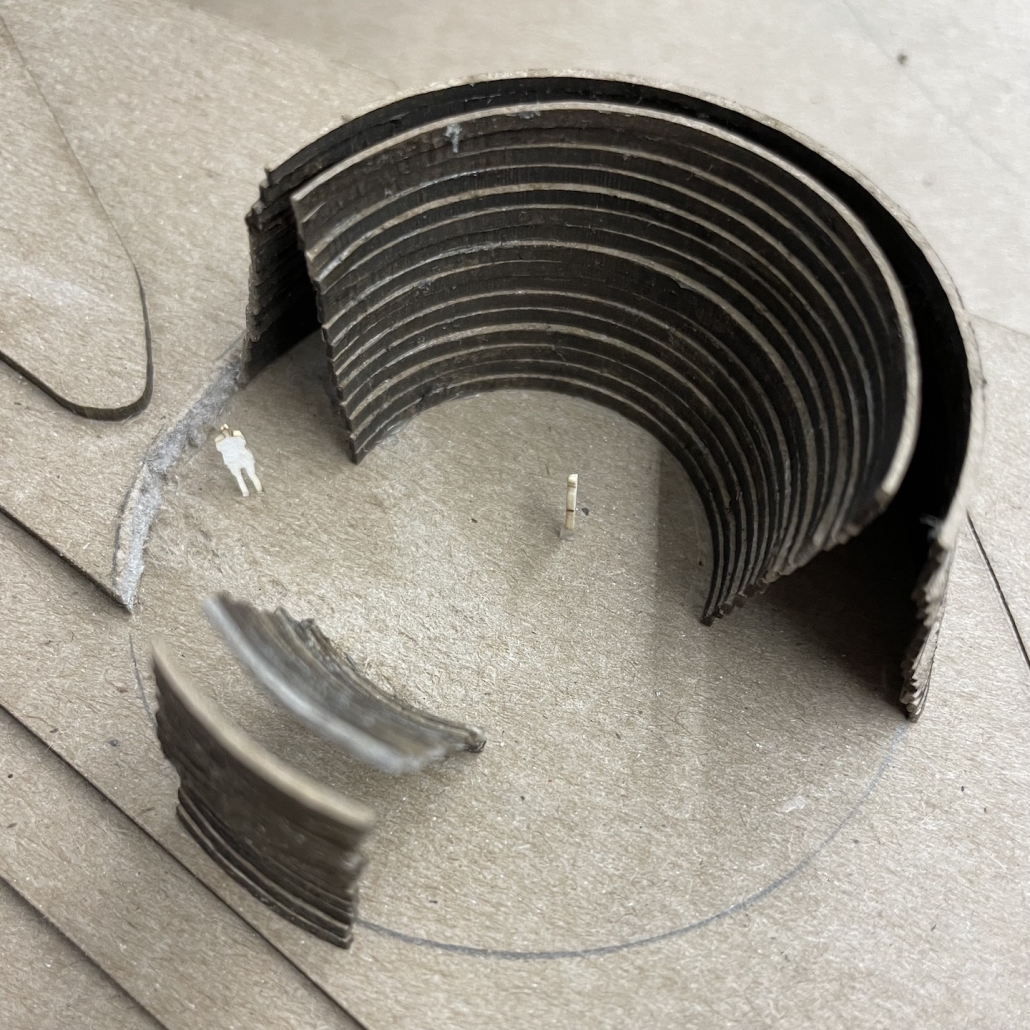

Toronto’s Terrestrial Reefs explores the design potentials of BioRock, an underutilized accreting material that simulates the reef-building processes of corals. BioRock is a grown limestone, alternative to concrete with a design agency that has many positive benefits including its ability to act as an ecological scaffold, sequester pollutants, and be highly sustainable. This work proposes three speculative applications of BioRock within urban Toronto that go beyond the typical marine-based applications that this material has been historically restrained to. These include the reintroduction of Alvar habitats as a landscape strategy, the remediation of obsolete reservoirs for BioRock production, and the in-situ repair of concrete bents supporting the Gardiner Expressway.

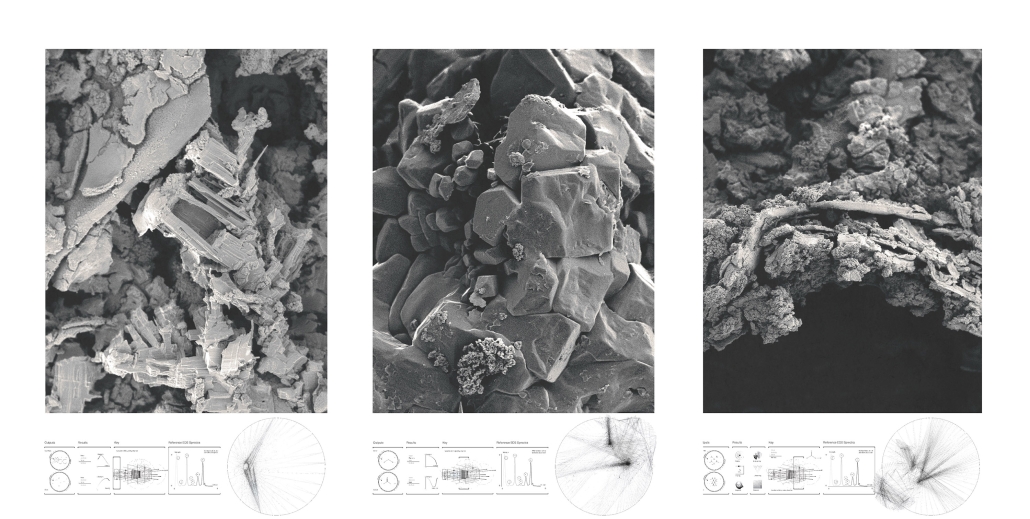

The research approach included material experiments, lab work, and data analysis. A series of experiments were conducted that tested various morphologies and growing conditions within a self-made wet lab. This means of working developed an understanding of the material from a hands-on perspective to speculate upon new uses for architectural design. Next, interviews were conducted with an interdisciplinary team of consultants which promoted conversations between research in material ecology and landscape ecology. First, a Professor of Biology and coral reef researcher, Dr. Nigel Waltho. This conversation shed insight on BioRock’s limiting factors including its growth rate. Second, a Professor of Chemistry, Dr. Bob Burk, spoke to the practicalities of BioRock industrial-scale synthesis. Thirdly, an Electrical Engineer, Dr. Jianqun Wang from the Carleton Nano Imaging Facility lab. By working with Dr. Wang, material samples were analyzed under a scanning electron microscope to determine the type of BioRock produced, the relative strength of the material, and its capabilities in the repair of concrete at the nanoscale. Finally, a Landscape Ecologist, Dr. Jessica Lockhart from the Geomatics and Landscape Ecology Research Lab. Informed by the literature produced at her lab, a landscape strategy via a habitat network modeling script was developed.

The resulting design was explored through these experimental models and test fragments of BioRock which formed a library of artifacts that traverse biogeochemical scales of speculation, assembling a collection of work in the form of a Terrestrial Reef.

This project won the Maxwell Taylor Prize.

Instagram: @_campenney

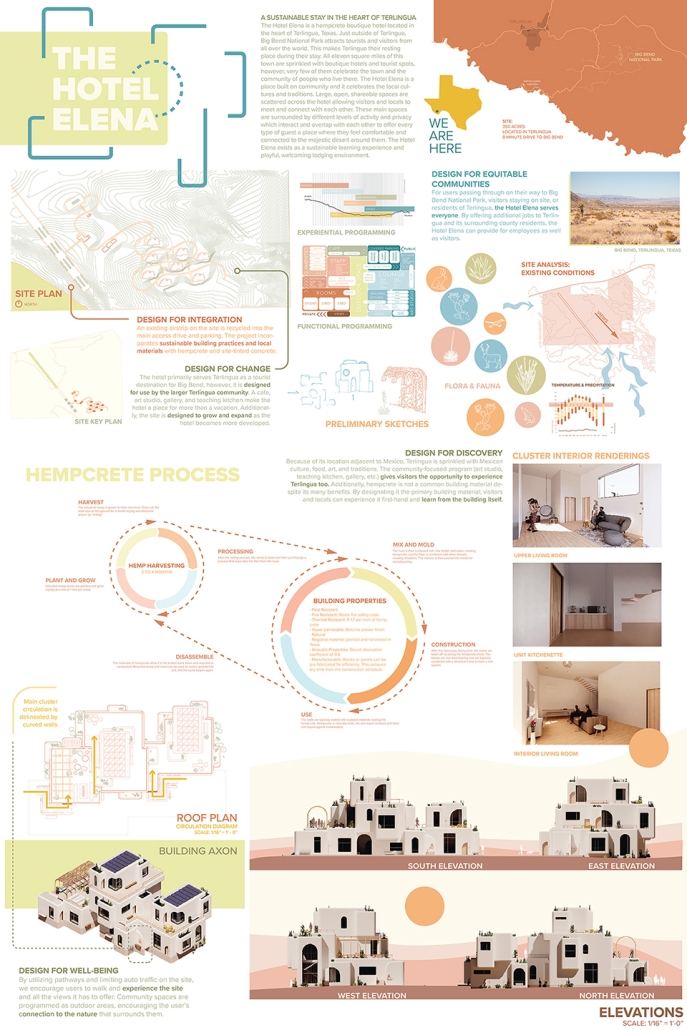

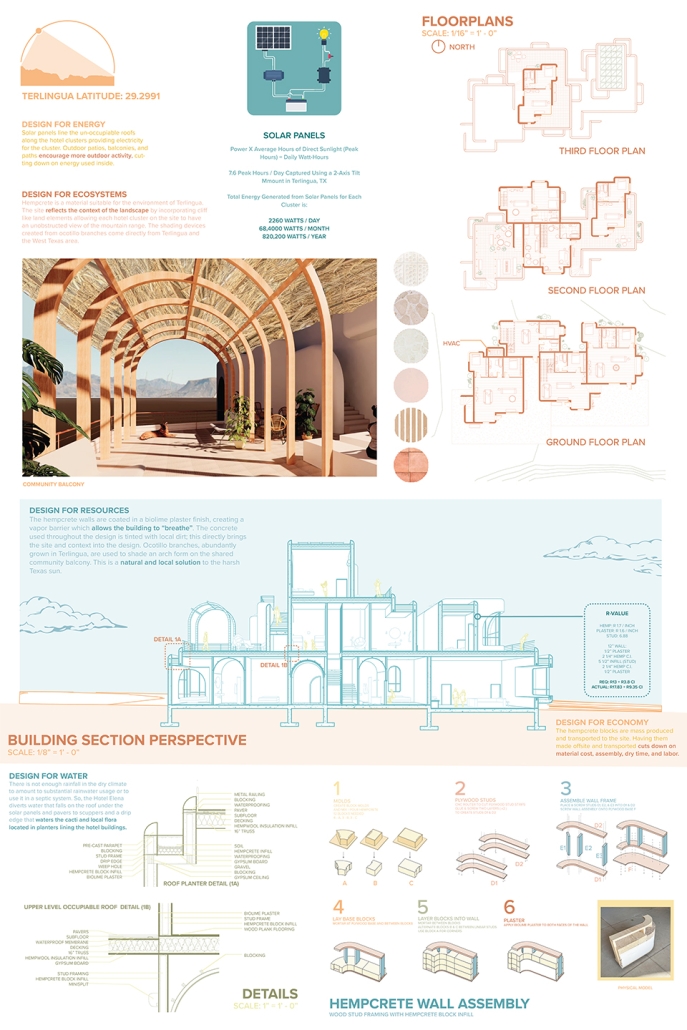

Hotel Elena by Kristi Saliba, B.Arch ‘23

University of Oklahoma | Advisor: Amy Leveno

Viva Terlingua!

The initial phase of this fifth-year undergraduate studio will run as part science lab/part sculpture studio/part fabrication shop. Students will break up into teams to research, explore, and document the process of creating hempcrete through hands-on explorations.

The second part of this studio will explore the role of natural building and hospitality through the design of a boutique hotel in Terlingua, Texas, a town just outside an entrance to Big Bend National Park. Students will work in teams to create a building that responds appropriately to the harsh beauty of the surrounding landscape through high design with a focus on natural building systems and sustainability. Students will also select their individual project sites around the area, define their target clientele, and craft a program that appropriately serves that site and demographic.

Knitting together the first and second parts of the studio will be the fabrication of a full-size wall section demonstrating how hempcrete is utilized in a typical wall section.

Instagram: @kristi.saliba

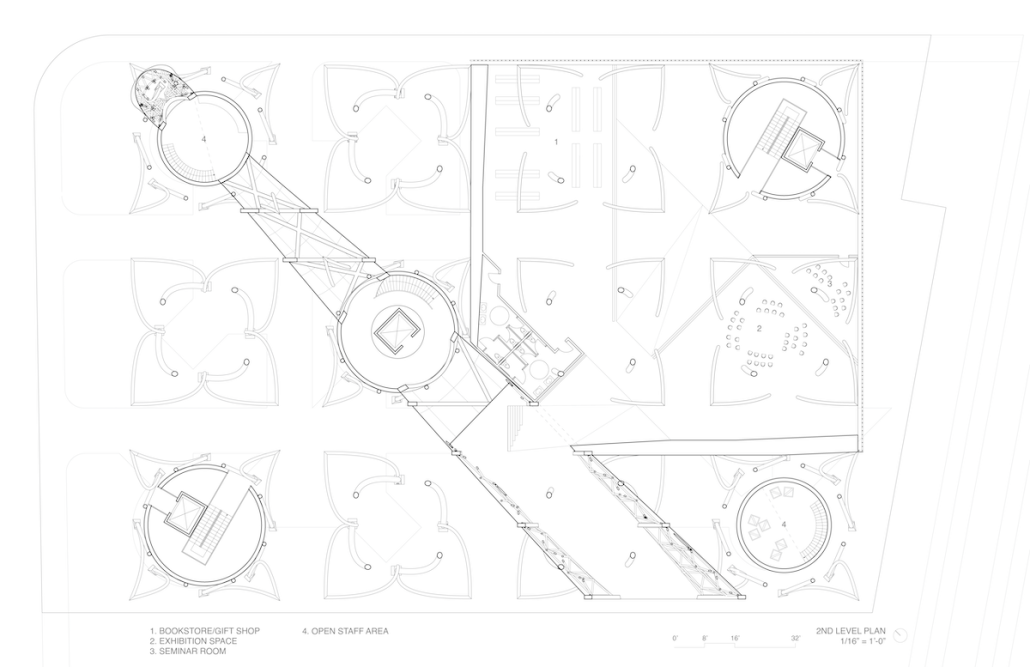

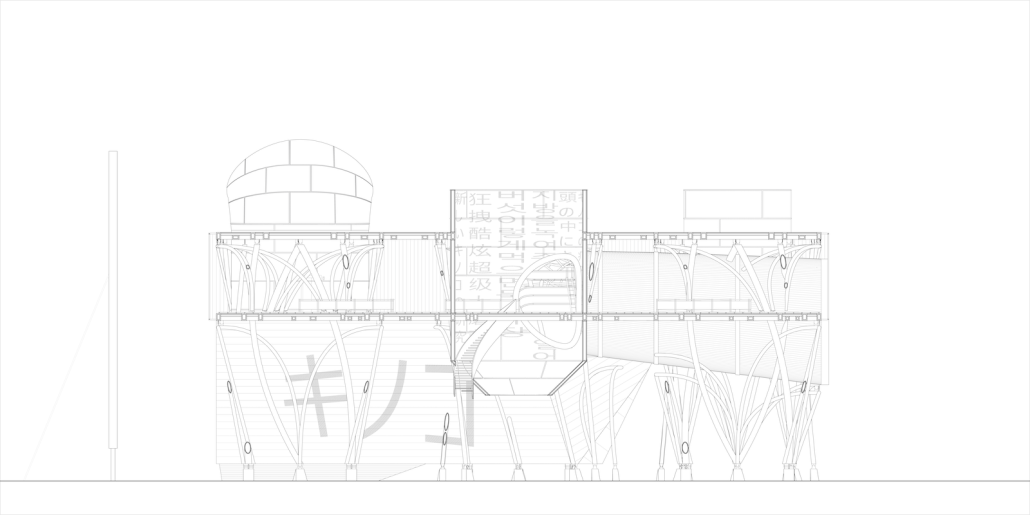

Fungus Among Us by Yitao Guo & Kinamee Rhodes, M.Arch ‘23

UCLA Architecture and Urban Design | Advisor: Simon Kim

Architecture of the future will be built with mycelium – the root structure of fungi. Mycelium is a renewable building material, currently in an experimental stage in the form of lightweight bricks, insulation, and flooring. This facility is dedicated to expanding the possibilities of this material, envisioning a post-anthropocentric world of mycological architecture. A forest of bent steel creates a pliant stack-floor building with post-into beams that allow for bounce and deflection. A bio-tunnel for cultivation and circulation intersects with the big-box typology. The spaces inscribed but never enclosed in the building reference Archizoom, lshigami, and Toyo Ito with their extensibility and density. Ultimately, the orchestration of sloping slabs and inside/outside structural clusters is a re-imagination of the principles of a myco-Raumplan.

Learning From Yucatan by Anna Hartley & Maggie Jaques, M.Arch ‘23

Kansas State University | Advisors: David Dowell, Ted Arendes, Salvador Macias, Magui Peredo & Diego Quirarte

LEARNING FROM YUCATAN: EXPLORATION JOURNEY THROUGH A SUSTAINABLE IDEA OF PLACE

Mexico is a very diverse cultural and natural mosaic. We have had the opportunity to work in several parts of the country, from our location in Guadalajara. Somehow we have worked as “foreigners” in our own country. However, from that foreign perspective, we have found particularly in the Yucatan Peninsula a place of enormous learning and a source of inspiration that continues to captivate us.

This region of the country is one of the most prolific in its biodiversity, abundance of natural resources, and extraordinary cultural past.

The Yucatan Peninsula witnessed the flourishing of the Mayan Culture. In Yucatan, a large part of the population today is still Mayan. Despite having more than two thousand years of existence, the Mayan communities still speak the original dialect, they give continuity to the gastronomic tradition, and above all, keep on living the same way: in small complexes that become a house, a bedroom, a garden, an orchard, a farmyard, a kitchen, etc. This fascinating and sustainable phenomenon has attracted and moved us deeply.

All of this has made the Yucatan Peninsula a huge international tourist magnet, but also a place of pilgrimage for contemporary life that seeks a sustainable, peaceful way of life, connected with nature and respectful of the environment. As if the Mayan way of life, in a certain sense, began to be “adopted” as a way of life by followers of their culture.

In 1972, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown published “Learning From Las Vegas,” the research project they made with their students understanding the city. Calling for architects to be more receptive to the ordinary and to overcome the forgotten idea of “symbolism” in modern architecture at the time.

The studio attempts, through the title, to recall this model of study and tries to provoke students to board on a similar journey of exploration. Like a foreigner who tries to examine a new and adverse territory, and interact with it without prejudgment in order to learn from it. That is why we introduce one of the many drawings that Frederick Catherwood made when he joined the American explorer John Lloyd Stephens on his discovery journey of the Yucatan Peninsula in 1839 and that they would publish in 1841.

From the learning and the reflection, we will invite students to produce contemporary ways of living based on the principles, the ways of life, the local conditions, and the ways of making this unique place.

This project won the 2023 Kremer Prize for Best Group Project.

Instagram: @ksudesignmake

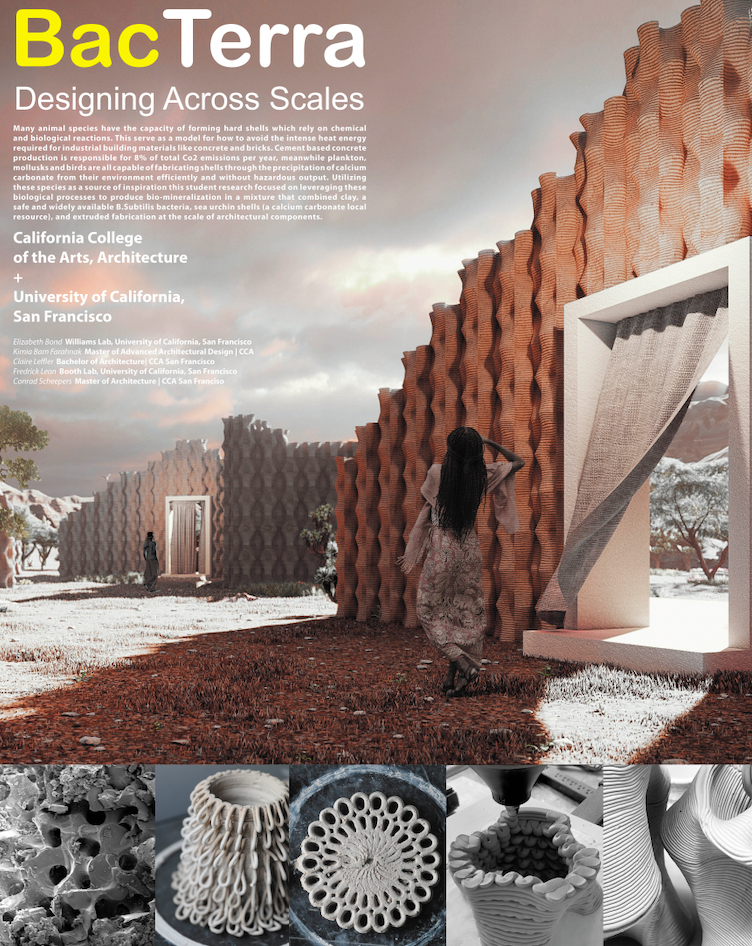

BacTerra: Designing Across Scales by Claire Leffler & Kimia Bam Farahnak,B. Arch, MAAD ( M. Advanced Arch Design) ‘23

California College of the Arts, Architecture Division | Advisors: Margaret Ikeda, Evan Jones & Negar Kalantar

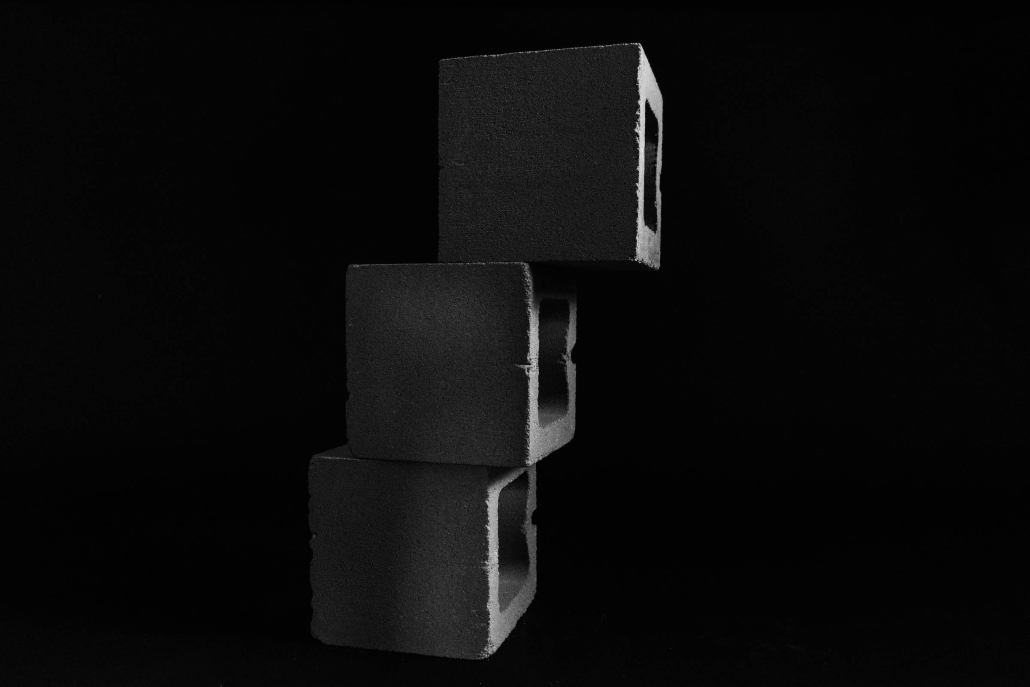

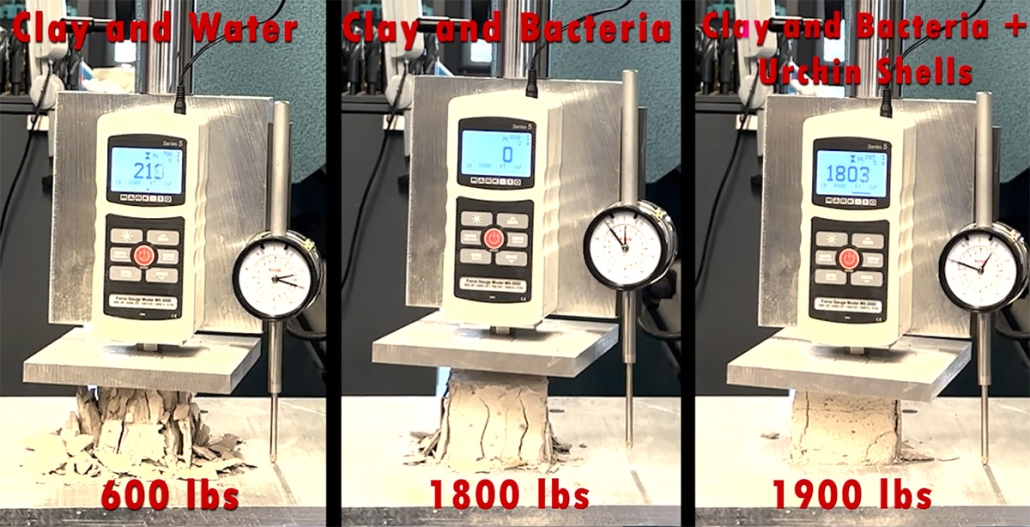

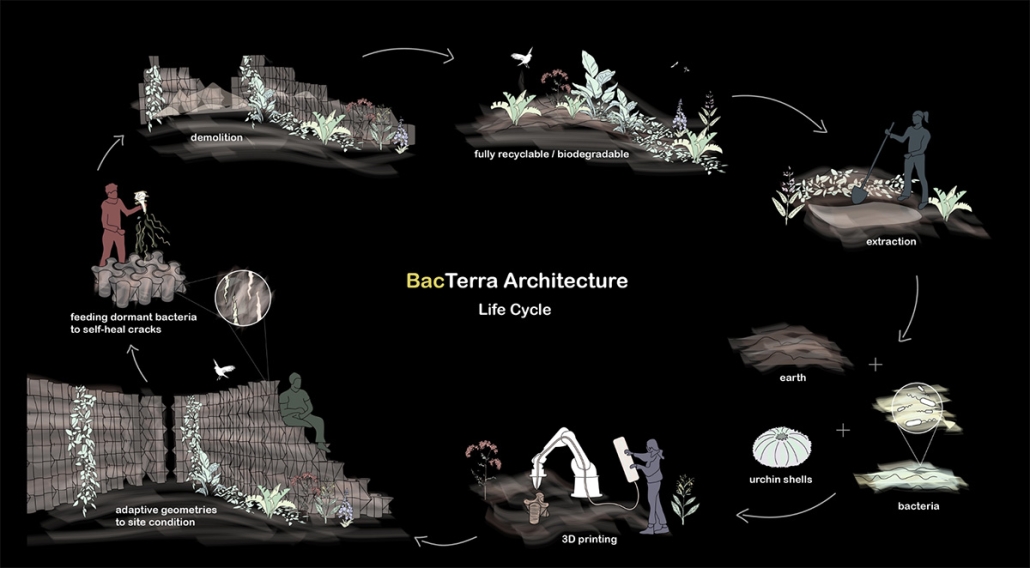

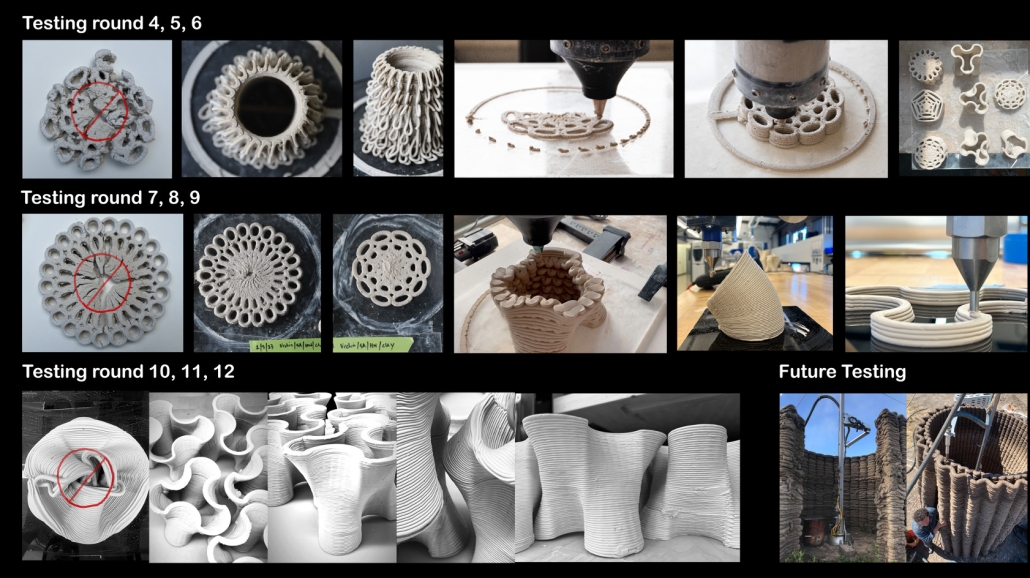

The research goal of BacTerra is to investigate the potential for a biomaterial to reduce embodied carbon in building components and to be accessible to communities around the world. Many animal species have the capacity to form hard shells which rely on chemical and biological reactions. This serves as a model for how to avoid the intense heat energy required for industrial building materials like concrete and bricks. Cement-based concrete production is responsible for 8% of total Co2 emissions per year, meanwhile, plankton, mollusks and birds are all capable of fabricating shells through the precipitation of calcium carbonate from their environment efficiently and without hazardous output. Utilizing these species as a source of inspiration the student research focused on leveraging these biological processes to produce bio-mineralization in a mixture that combined clay, a safe and widely available B.Subtilis bacteria, sea urchin shells (a calcium carbonate local resource), and extruded fabrication at the scale of architectural components.

This thesis was a BioDesign Challenge top 8 finalist and received the Outstanding Science Award.

Instagram: @architecturalecologieslab

MUTUALISME, Symbiotic bio-organization at the service of a living program by Anaïa Duclos, M.Arch. ‘23

University of Montreal | Advisor: Andrei Nejur

This project uses architecture to slow down the intensive transformation of territory by the food production sector. Between 2019 and 2020, 1,362,000 tonnes of construction waste were discarded. This represents 28% of all landfill waste in Québec. Gypsum board partitions are extremely prevalent in buildings and urban environments, but they are also highly polluting. During their deconstruction, they are mostly thrown away and buried in landfills.

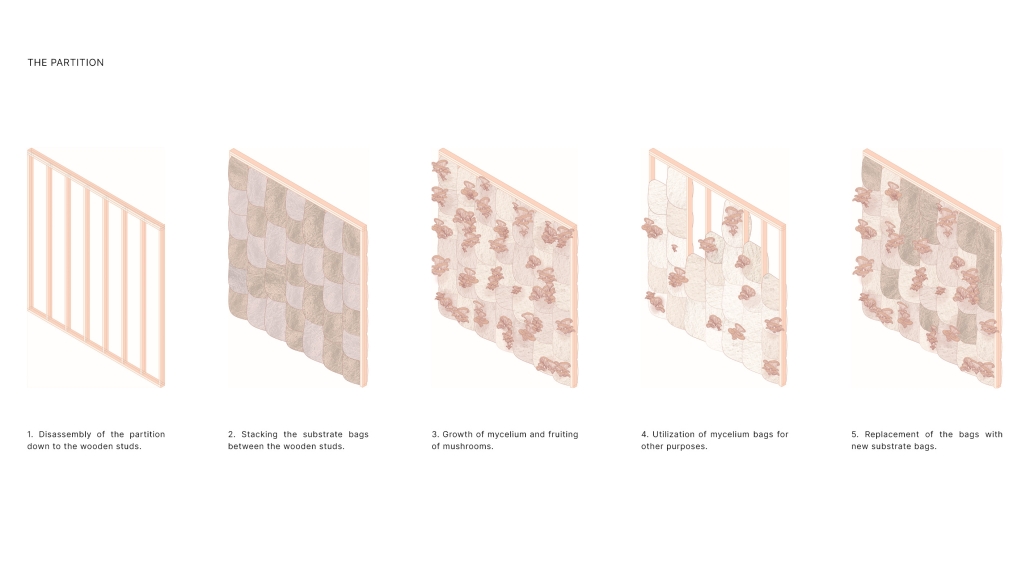

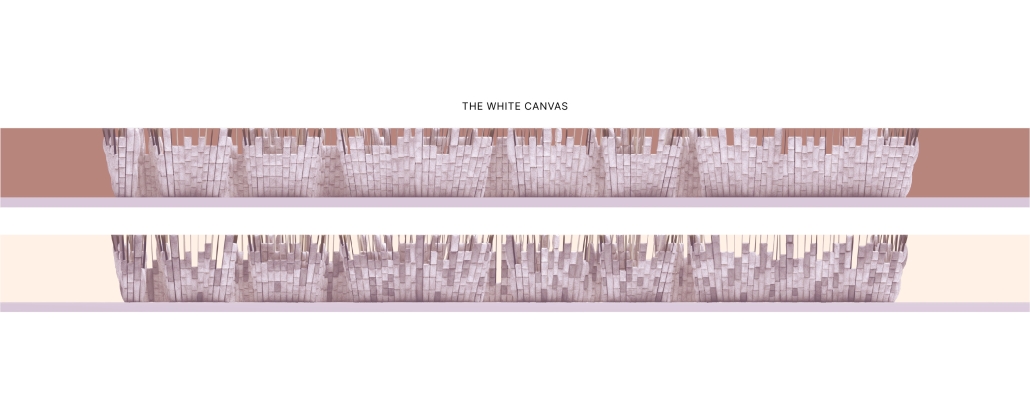

The project reappropriates gypsum board partitions to create a productive wall, thus slowing down the transformation of the territory. It addresses a new vital human need beyond that of housing, it provides food as well.

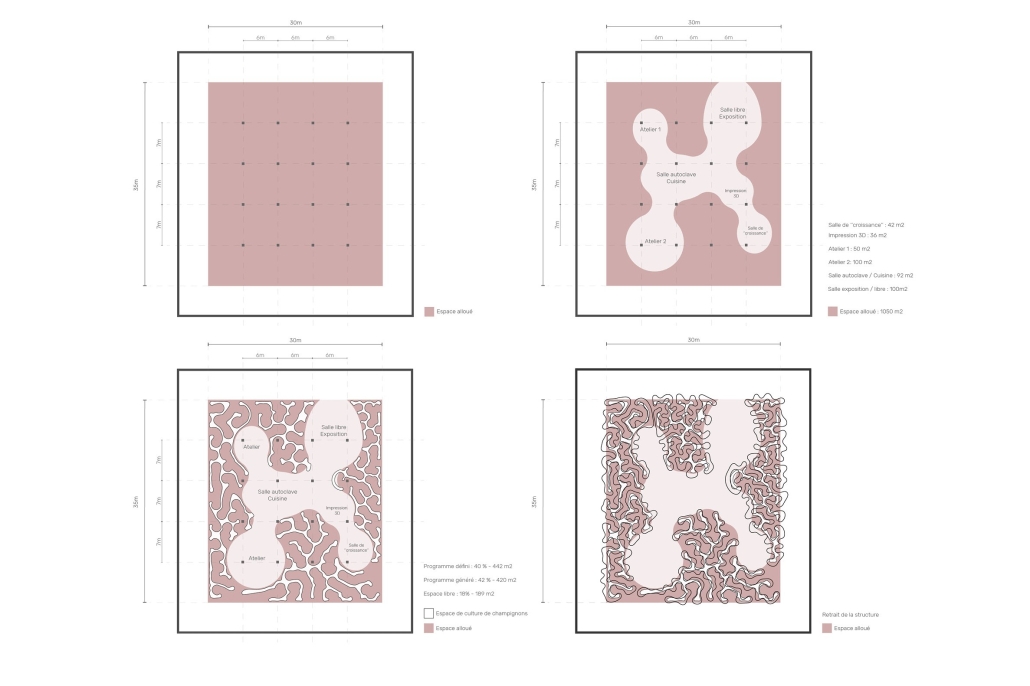

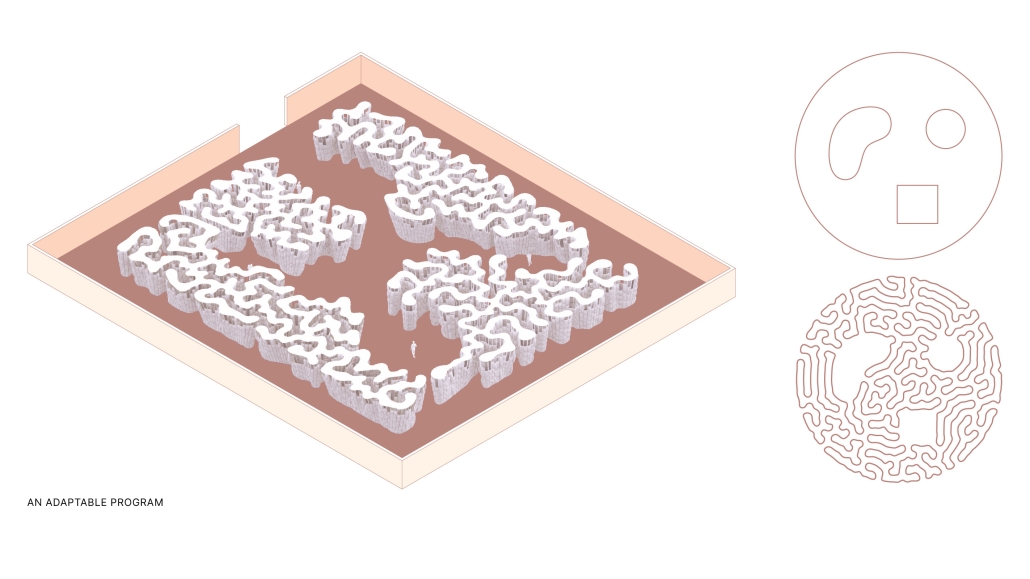

The living program is defined by the production of mushrooms through the structure of the traditional gypsum board partition. It infiltrates unused space and adapts to optimize its surface within a given area. Cracks and folds in the structure increase the surface area where mushrooms can grow. The human program offers workshop rooms on mycelium and its usage, creating a learning center for mycomaterials. Surrounding this program where human activities take place, is the living program in constant growth.

The process enriches the neighborhood users as well as the living program. Local residents bring their waste to the learning center, which serves as a substrate for the mycelium to enhance production. The transformed mycelium can then be collected by visitors, and the mushrooms are harvested for consumption. The result is a symbiotic relationship and mutual enrichment at the heart of the city.

Instagram: @anais.duclos, @nejur.xyz, @fac_ame_umontreal, @architecture.udem

See you in the next installment of the Student Showcase!