University of Minnesota Symposium on Architecture and Biology

(via Architect Magazine)

In April, several University of Minnesota colleagues and I hosted the symposium “Biologically Motivated,” in Minneapolis, to explore connections between architecture, art, and biology. Our interdisciplinary graduate group shares a common interest in the ways that creative fields are increasingly looking to biology for inspiration and guidance. We are also curious about how different fields approach working with biology and biological principles.

To probe these and other questions, we invited a representative associated with each of three disciplines—architecture, art, and biology—to give a public talk and participate in a shared panel discussion: Jeff Karp, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard University Medical School’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston; Amy Youngs, an associate professor of art at The Ohio State University, in Columbus, Ohio; and David Benjamin, an assistant professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and the founding principal of The Living, in New York.

While the lecturers, in their talks, focused on their own work, their collective presence highlighted several points of intersection, revealing strategies and raising implications for all disciplines interested in developing a closer relationship with biology.

Tracing Outcomes

One commonality concerns the measurable benefits that such work can deliver, despite its inherent difficulties. Karp, who is a biomedical engineer, described the near-insurmountable challenges his research team faced when developing a solution for individuals with atrial septal defect—a hole between the heart’s upper chambers. Working with colleagues at Gecko Biomedical, based in Paris, they developed a viscous, hydrophobic surgical glue inspired by several organisms, including snails and ivy. Composed entirely of organic materials, the biocompatible adhesive promises much higher success rates than existing sutures or medical-grade superglue.

In her 2010 installation at the Redline Gallery, in Denver, Youngs went beyond emulating biology to employing it. The highly interactive “River Construct” exhibit models a waterfront ecology with flowing water, vegetation, a domestic rabbit that generates feces, and worms that decompose it, providing nutrients for the plants.

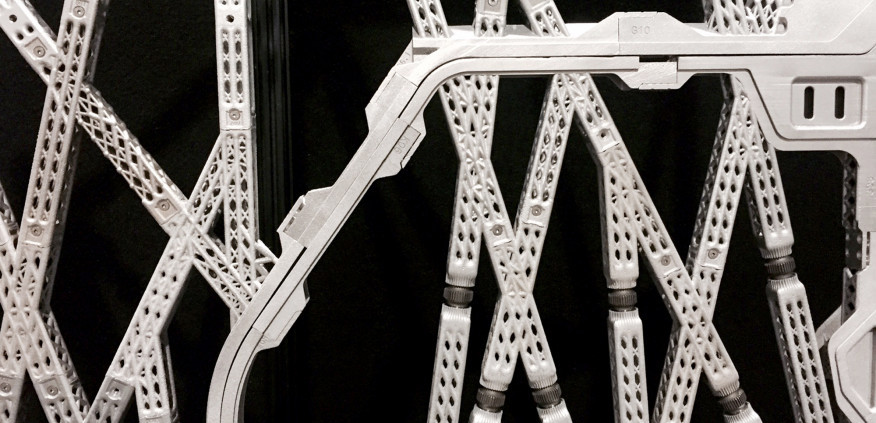

In the case of The Living’s Bionic Partition Project (top image), Benjamin created an optimized component for aircraft maker Airbus based on hundreds of computer-generated design permutations derived from natural structures. By utilizing this bio-computation process, he was able to generate a 3D-printed aircraft partition that is stronger and nearly 50 percent lighter than existing designs.

Rethinking Existing Paradigms

Another shared attribute among the lecturers was their unexpected approaches to typical circumstances, redefining current habits and practices. The Karp Laboratory’s solution to a nickel allergy—a skin ailment affecting between 10 percent and 15 percent of the U.S. population—isn’t wearing gloves, avoiding physical contact with metal objects, or using a conventional skin lotion. Rather, Karp and his colleagues developed a skin cream composed of calcium carbonate nanoparticles that bind with the nickel ions to ensure that the particles are too large to penetrate the epidermis.

Youngs’ 2008 “Cute Parasite” project (shown above) is a whimsical critique on existing cactus-related horticultural practices such as grafting and fluorescence, both of which require human intervention. The installation, which was featured at the the Hybrids Matchmaking exhibition in Trondheim, Norway, included cacti grafted with unanticipated elements such as bird feathers, rabbit fur, and colored twine, calling attention to these often-unquestioned techniques.

And Benjamin’s much-documented Hy-Fi pavilion, the winning entry to the 2014 MoMA PS1 competition, was clad in building modules made from mycological biocomposites instead of conventional bricks. The 10,000 lab-grown blocks had much less embodied energy than kiln-fired masonry and were composted after the event to enrich the soil of nearby community gardens.

(via Architect Magazine)

—

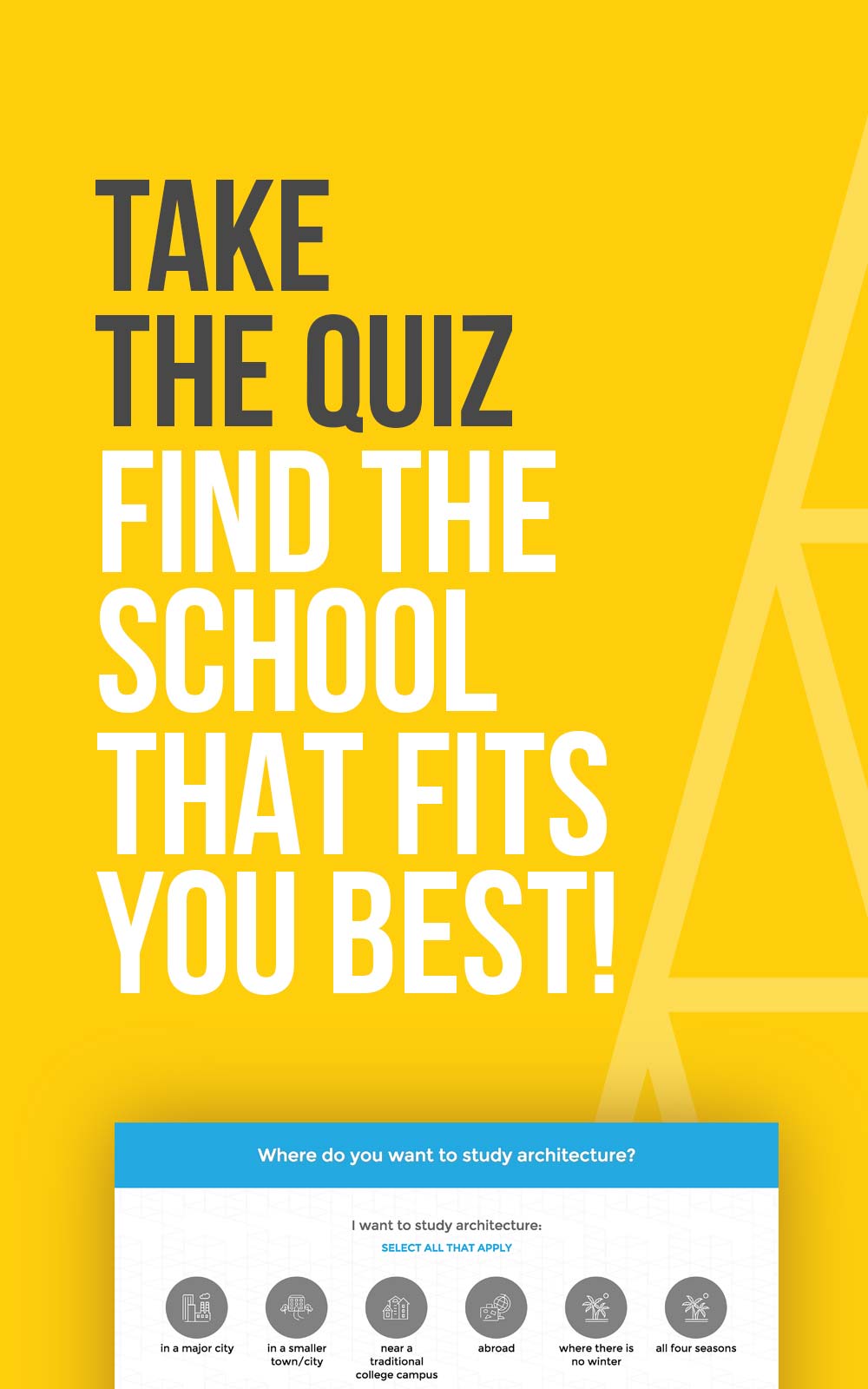

More on University of Minnesota’s Architecture Program here!