Study Architecture Program Spotlight: Tulane University’s URBANbuild Program

As an architecture student, you have the opportunity to access various programs that will expand your skills and provide you with hands-on experience. At Tulane University, URBANbuild is an award-winning design-build program that allows students to gain firsthand experience building homes in their local community in New Orleans, Louisiana.

The program was founded in 2005, with plans to launch that fall semester. However, the city of New Orleans was devastated when Hurricane Katrina made landfall later that August. Hurricane Katrina was one of the deadliest and costliest hurricanes in U.S. history. According to URBANbuild’s website, “the city was left 80 percent damaged with the population immediately reduced to one-third.”

(Image Credit: Tulane University)

(Image Credit: Tulane University)

“[Hurricane Katrina] really messed up our plans to start this new program, but more importantly and more rewardingly, it gave our program a new mission,” said Byron J. Mouton, Senior Professor of Practice at the Tulane University School of Architecture and Director of URBANbuild.

As New Orleans prioritized rebuilding, URBANBuild shifted its gears to not only assist in revitalizing the city but to also address New Orleans’ pre-Katrina problems including hesitancy to accept change. “When we first stepped into these communities, they were hesitant to buy into what we were doing,” said Mouton. “But then the second year came around and we returned and they were a little more receptive. And then it wasn’t really until we were there for three or four years that the community felt comfortable enough to engage with us.”

Community engagement and involvement is one of the most important qualities of URBANbuild. The program partners with local organizations including Bethlehem Lutheran Church, the Neighborhood Housing Services of New Orleans (NHS), and Urban Fabric. “We had to build that trust,” explained Mouton. “We also worked with an organization called Neighborhood Housing Services, which had been around before Katrina, and they specialized in helping people find ways to get homes. They were really the great connection between what we were doing as researchers and what the community needed.”

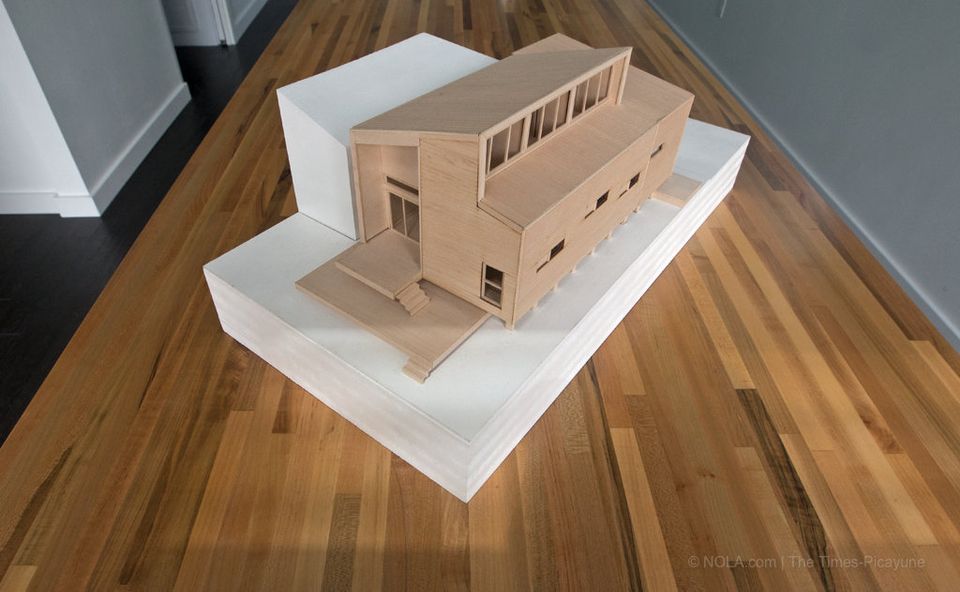

The URBANbuild program spans the fall and spring semesters, offering students the opportunity to engage in the home-building process from concept to construction. The fall semester focuses on planning and research. Participating students are tasked to investigate housing strategies, permitting regulations, drafting construction documents, the cultural fabric of the community, and other key considerations.

“[During the fall semester,] we get together with the students and we have a little in-studio competition. We identify our topic of research. They each develop a strategy, and then one is chosen. They select one at midterm, and then they work on the construction documents between midterm and the end of the semester,” explains Mouton.

Students get hands-on building experience as they begin the construction process during the spring semester. “We break ground in January of the spring semester and build the house by May,” Mouton continues.

(Image Credit: URBANbuild)

Over the span of 16 weeks, students learn construction techniques, communicate with tradespeople, and watch their project come to life. “[The students don’t come in with construction experience], but they do have the desire to learn and they work hard,” says Mouton. “And to be clear, they do everything except I have to hire an electrician, a plumber, and an air conditioning consultant installer. And then once in a while I’ll have a crew hang the sheetrock, but they do everything else.”

By the end of the semester, students are able to celebrate the product of their research, construction, and teamwork: a fully built home. Finished projects include tiny houses, single-family homes, duplexes, mixed-use facilities, and more.

According to UrbanBuild’s website, it’s during the spring semester that students develop strong bonds with the community’s residents. “Getting to work with NHS, I got to know the family [we worked with] very well, and I’ve been able to visit them years after,” shared URBANbuild alumna Karla Valdivia. “It’s great to get to know the family because you are creating something that really affects them. It has a very personal feel.”

Recently, URBANbuild garnered national attention when the program was featured on CBS News. Aired in October 2024, the segment highlighted 63-year-old Benjamin Henry moving into his new home, thanks to the work of Tulane students. In four months, the students transformed a vacant plot of land into Henry’s “forever home.” Formerly unhoused for over a decade, Henry shared his excitement for the new chapter and expressed his heartfelt thanks to the students. “Building someone’s forever home is crazy and so rewarding,” said Tulane graduate Elliot Slovis.

Graduates of the URBANbuild program have gone on to become licensed architects and designers. They credit the program for providing them with an in-depth understanding of the construction process and emphasizing the importance of community engagement. “[URBANbuild] gives you the real-life experience of what life is like after school,” shared Valdivia.

Design-build programs like URBANBuild are a great way to expand your skillsets and gain real-world experience before graduation. Visit the URBANBuild website to learn more about the program, browse the curriculum, and view finished projects.

Interested in learning more about Tulane University’s School of Architecture? Click here!

Questions about the URBANbuild program? Please contact Byron Mouton (bmouton@tulane.edu).