2020 Student Thesis Showcase - Part I

Have you ever wondered what students design in architecture school? A few years ago, we started an Instagram account called IMADETHAT_ to curate student work from across North America. Now, we have nearly 3,000 projects featured for you to view. In this series, we are featuring thesis projects of recent graduates to give you a glimpse into what architecture students create while in school. Each week, for the rest of the summer, we will be curating five projects that highlight unique aspects of design. In this week’s group, the research ranges from urban scale designs focused on climate change to a proposal for a new type of collective housing and so much in between. Check back each week for new projects.

In the meantime, Archinect has also created a series featuring the work of 2020 graduates in architecture and design programs. Check out the full list, here.

Redefining the Gradient by Kate Katz and Ryan Shaaban, Tulane University, M.Arch ‘20

Thesis Advisors: Cordula Roser Gray and Ammar Eloueini / Course: 01-SP20-Thesis Studio

Sea level rise has become a major concern for coastal cities due to the economic and cultural importance tied to their proximity to water. These cities have sustained their livelihood in low-lying elevations through the process of filling, bridging, and raising land over coastal ecosystems, replacing their ecological value with infrastructures focused on defining the edge between city and nature. Hard infrastructures have been employed to maintain urban landscapes but have minimal capacity for both human and non-human engagement due to their monofunctional applications focused on separating conditions rather than integrating them. They produce short-term gains with long-term consequences, replacing and restricting ecosystems and acting as physical barriers in a context defined by seasonal transition.

To address the issues of hard infrastructure and sea level rise, this thesis proposes an alternative design strategy that incorporates the dynamic water system into the urban grid network. San Francisco was chosen as the location of study as it is a peninsula where a majority of the predicted inundation occurs on the eastern bayside. In this estuary, there were over 500 acres of ecologically rich tidal marshlands that were filled in during the late 1800s. To protect these new lands, the Embarcadero Sea Wall was built in 1916 and is now in a state of neglect. The city has set aside $5 billion for repairs but, instead of pouring more money into a broken system, we propose an investment in new multi-functional ecologically-responsive strategies.

As sea levels rise, the city will be inundated with water, creating the opportunity to develop a new circulation system that maintains accessibility throughout areas located in the flood zone. In this proposal, we’ve designed a connective network where instance moments become moments of pause and relief to enjoy the new cityscape in a dynamic maritime district.

On the lower level, paths widen to become plazas while on the upper level, they become breakout destinations which can connect to certain occupiable rooftops that are given to the public realm. The bases of carved canals become seeding grounds for plants and aquatic life as the water level rises over time. Buildings can protect high-risk floors through floodproofing and structural encasement combined with adaptive floorplates to maintain the use of lower levels. The floating walkway is composed of modular units that are buoyant, allowing the pedestrian paths to conform and fluctuate with diurnal tidal changes. The composition of the units creates street furniture and apertures to engage with the ecologies below while enabling a once restricted landscape of wetlands to take place within the city.

The new vision of the public realm in this waterfront district hopes to shine an optimistic light on how we can live with nature once again as we deal with the consequences of climate change.

Unearthing the Black Aesthetic by Demar Matthews, Woodbury University, M.Arch ‘20

Advisor: Ryan Tyler Martinez

Featured on Archinect

“Unearthing The Black Aesthetic” highlights South Central Los Angeles’s (or Black Los Angeles’s) unique positioning as a dynamic hub of Black culture and creativity. South Central is the densest population of African Americans west of the Mississippi. While every historically Black neighborhood in Los Angeles has experienced displacement, the neighborhood of Watts was hit particularly hard. As more and more Black Angelenos are forced for one reason or another to relocate, we are losing our history and connection to Los Angeles.

As a way to fight this gentrification, we are developing an architectural language derived from Black culture. So many cultures have their own architectural styles based on values, goals, morals, and customs shared by their society. When these cultures have relocated to America, to keep their culture and values intact, they bought land and built in the image of their homelands. That is not true for Black people in America. In fact, until 1968, Black people had no rights to own property in Los Angeles. While others began a race to acquire land in 1492, building homes and communities in their image, we started running 476 years after the race began. What percentage of land was left for Blacks to acquire? How then can we advance the development of a Black aesthetic in architecture?

This project, most importantly, is a collaboration with the community that will be for us and by us. My goal is to take control of our image in architecture; to elevate, not denigrate, Black life and culture. Ultimately, we envision repeating this process in nine historically Black cities in America to develop an architectural language that will vary based on the history and specificities of Black culture in each area.

KILLING IT: The Life and Death of Great American Cities by Amanda Golemba, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, M.Arch ’20

Advisors: Nikole Bouchard, Jasmine Benyamin, and Erik Hancock / Independent Design Thesis

For decades, post-industrial cities throughout the United States have been quietly erased through self-imposed tabula rasa demolition. If considered at all, demolition is touted as the mechanism for removing unsightly blight, promoting safety, and discarding the obsolete and the unwanted. Once deemed unworthy, rarely does a building survive the threat of demolition.

In the last decade, the City of Chicago has erased over 13,000 buildings with 225 in just the last four months. Not only does this mass erasure eradicate the material and the spatial, but it permanently wipes the remnants of human bodies, values, and history — a complete annulment of event, time, and memory.

But why do we feel the need to erase in order to make progress?

Our current path has led to a built environment that is becoming more and more uniform and sterile. Much of America has become standardized, mixed-use developments; neighborhoods of cookie-cutter homes and the excessive use of synthetic, toxic building materials. A uniform world is a boring one that has little room for creativity, individuality, or authenticity.

This thesis, “KILLING IT,” is a design proposal for a traveling exhibition that seeks to change perceptions of the existing city fabric by visualizing patterns of erasure, questioning the resultant implications and effects of that erasure, and proposing an alternative fate. “KILLING IT” confronts the inherently violent aspects of architecture and explores that violence through the intentionally jarring, uncomfortable, and absurd analogy of murder. This analogy is a lens through which to trace the violent, intentional, and premature ending and sterilization of the existing built environment. After all, as Bernard Tschumi said, “To really appreciate architecture, you may even need to commit a murder.”1 But murder is not just about the events that take place within a building, it is also the material reality of the building itself.

Over the life of a building, scarring, moments in time, and decay layer to create an inhabitable palimpsest of memory. This traveling exhibition is infused with the palimpsest concept by investigating strategies of layering, modularity, flexibility, transparency, and building remains, while layering them together to form a system that operates as an inhabitable core model collage. Each individual exhibition simultaneously memorializes the violence that happened at that particular site and implements murderous adaptive reuse strategies through collage and salvage material to expose what could have been.

If we continue down our current path, we will only continue to make the same mistakes and achieve the same monotonous, sterilizing results we currently see in every American city and suburb. We need to embrace a new path that values authenticity, celebrates the scars and traces of the past, and carries memories into the future. By reimaging what death can mean and addressing cycles of violence, “KILLING IT” proposes an optimistic vision for the future of American cities.

-

-

- Tschumi, Bernard. “Questions of space: lectures on architecture” (ed. 1990)

-

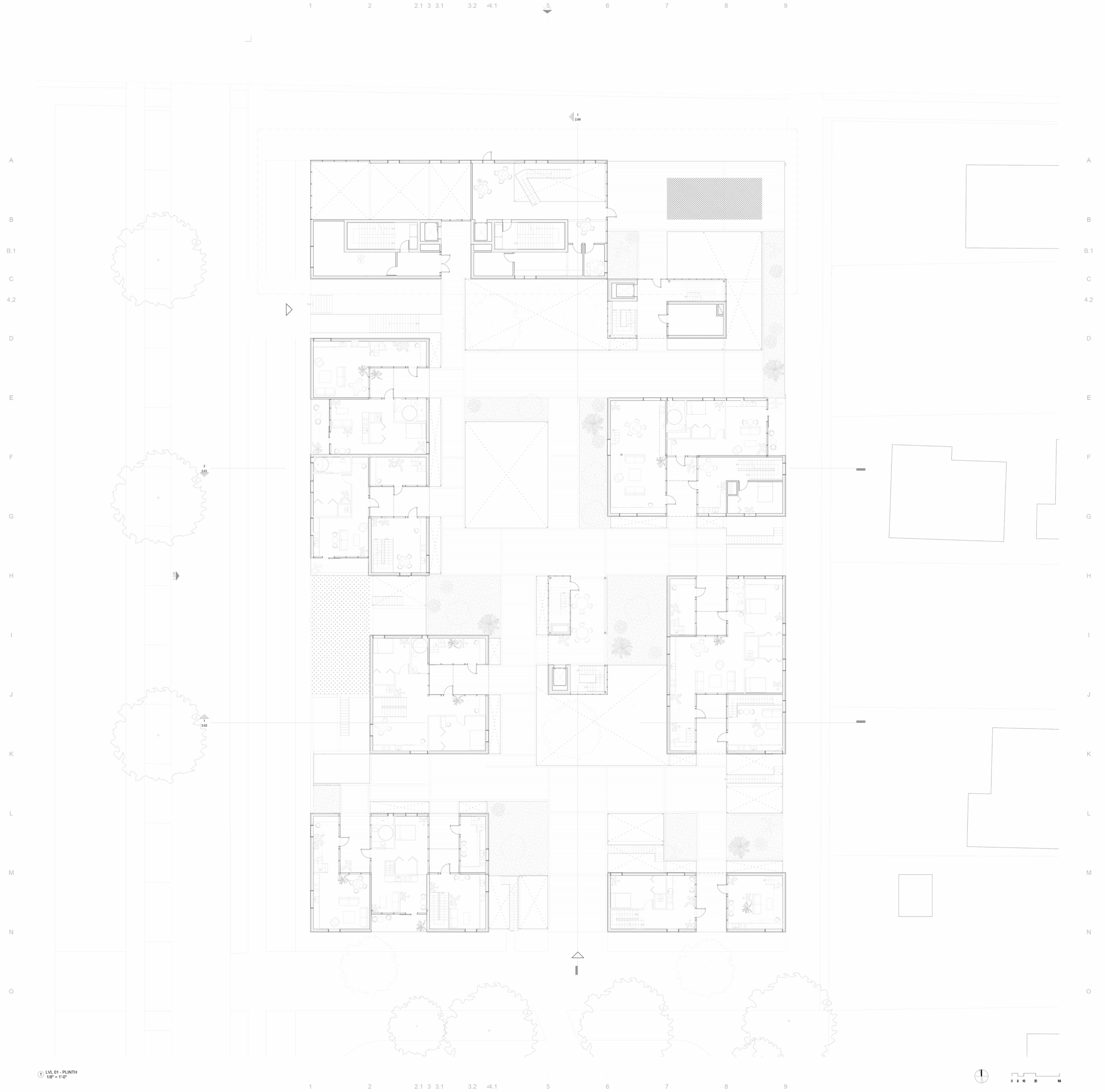

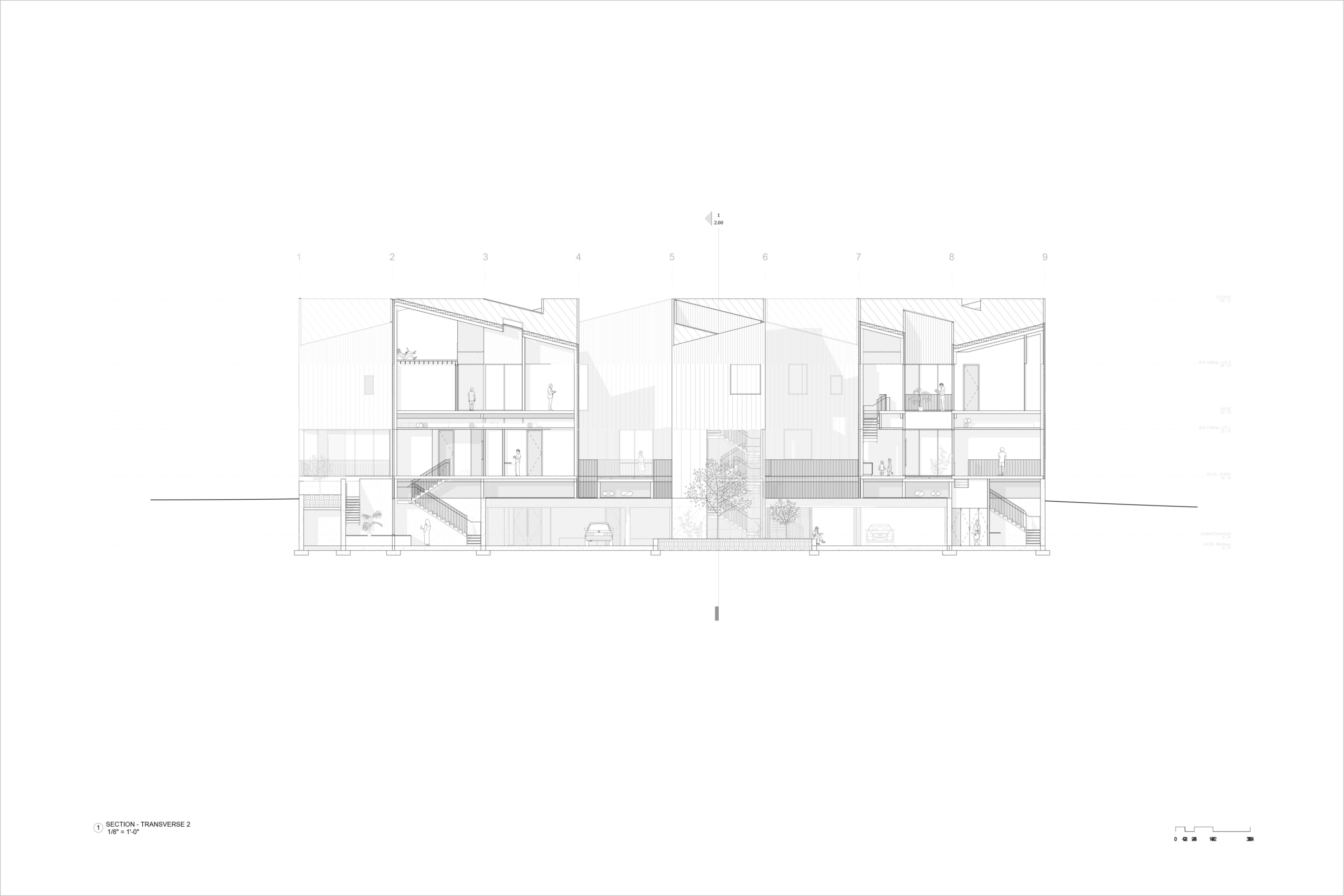

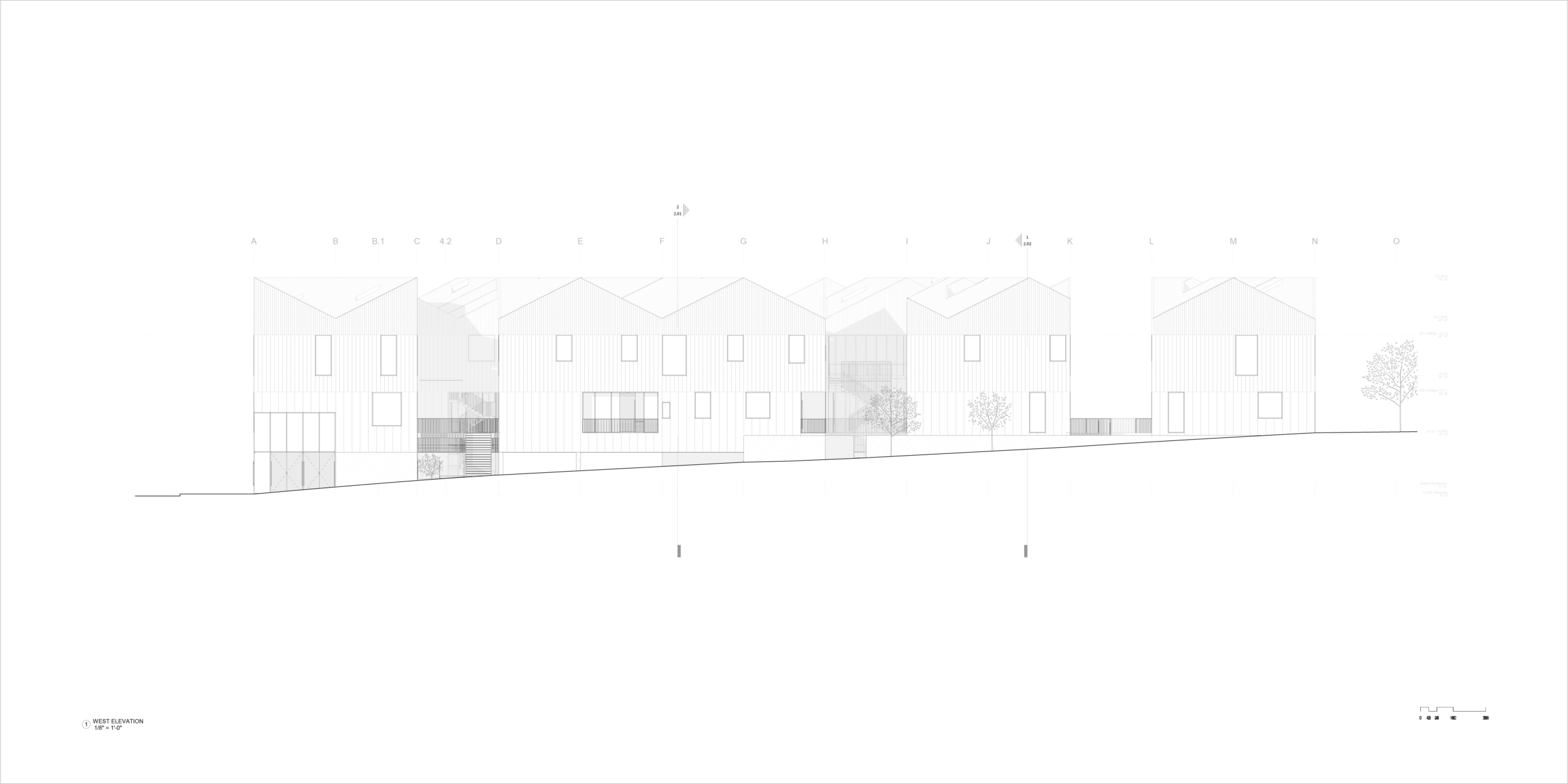

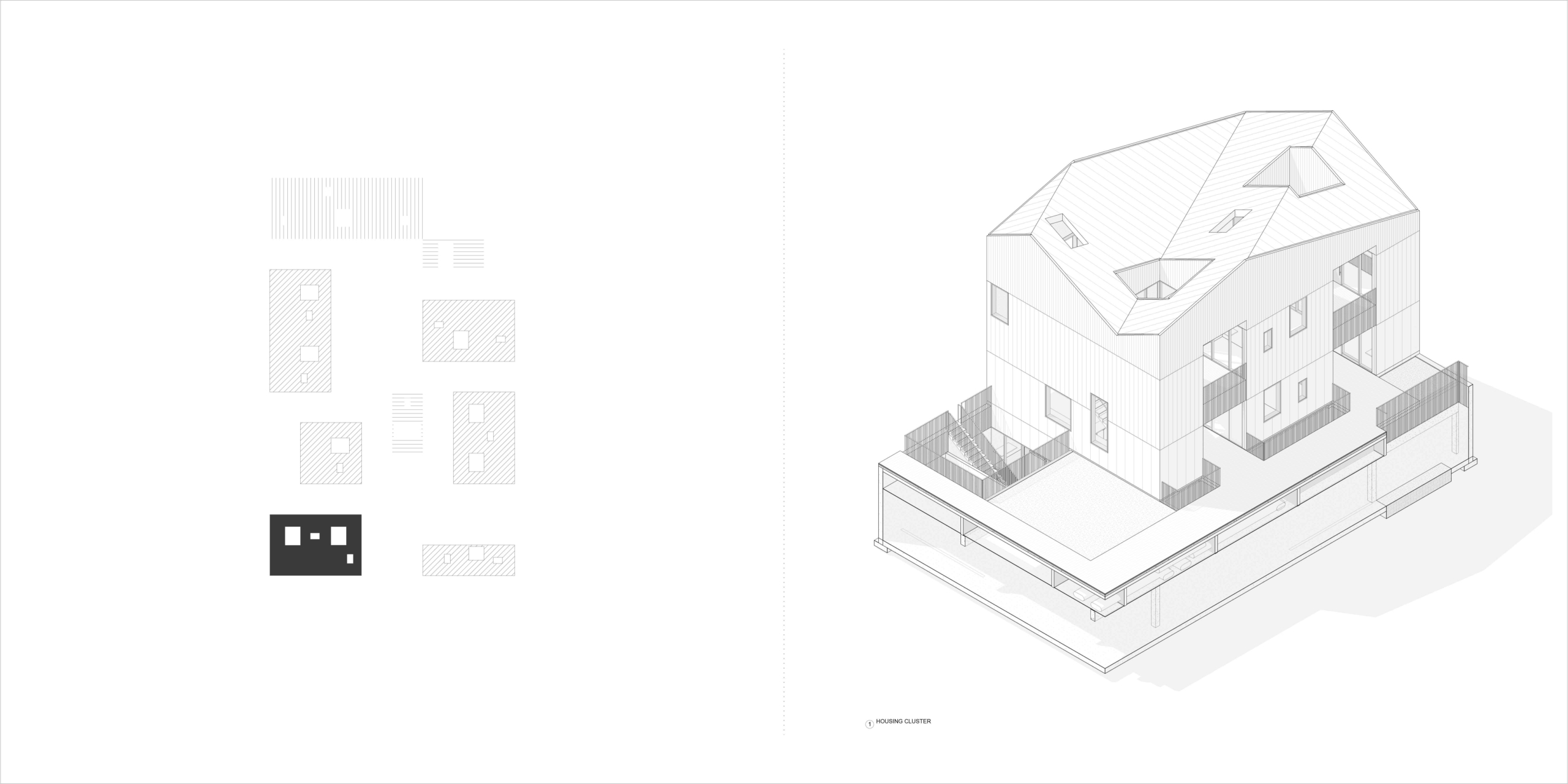

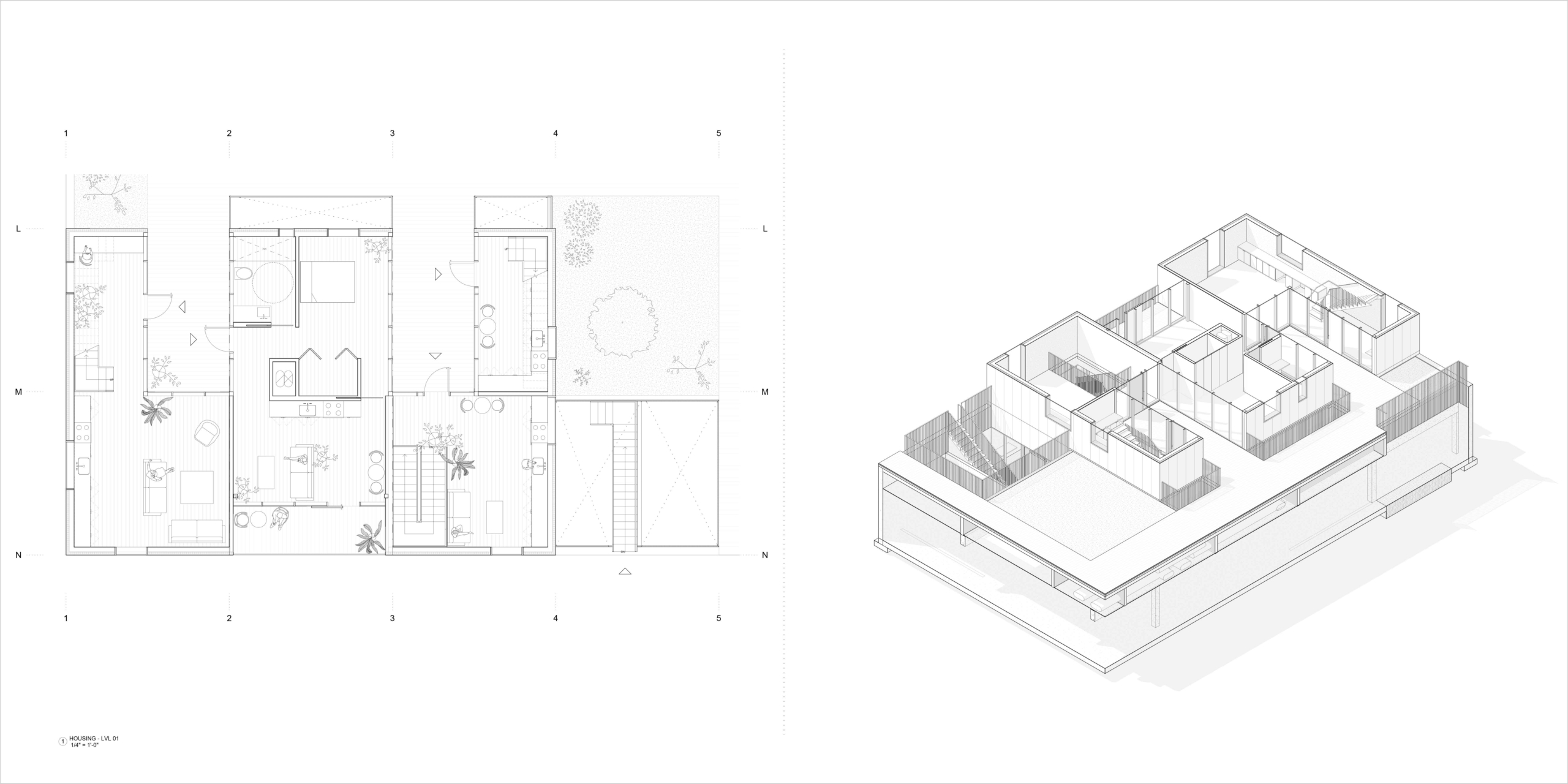

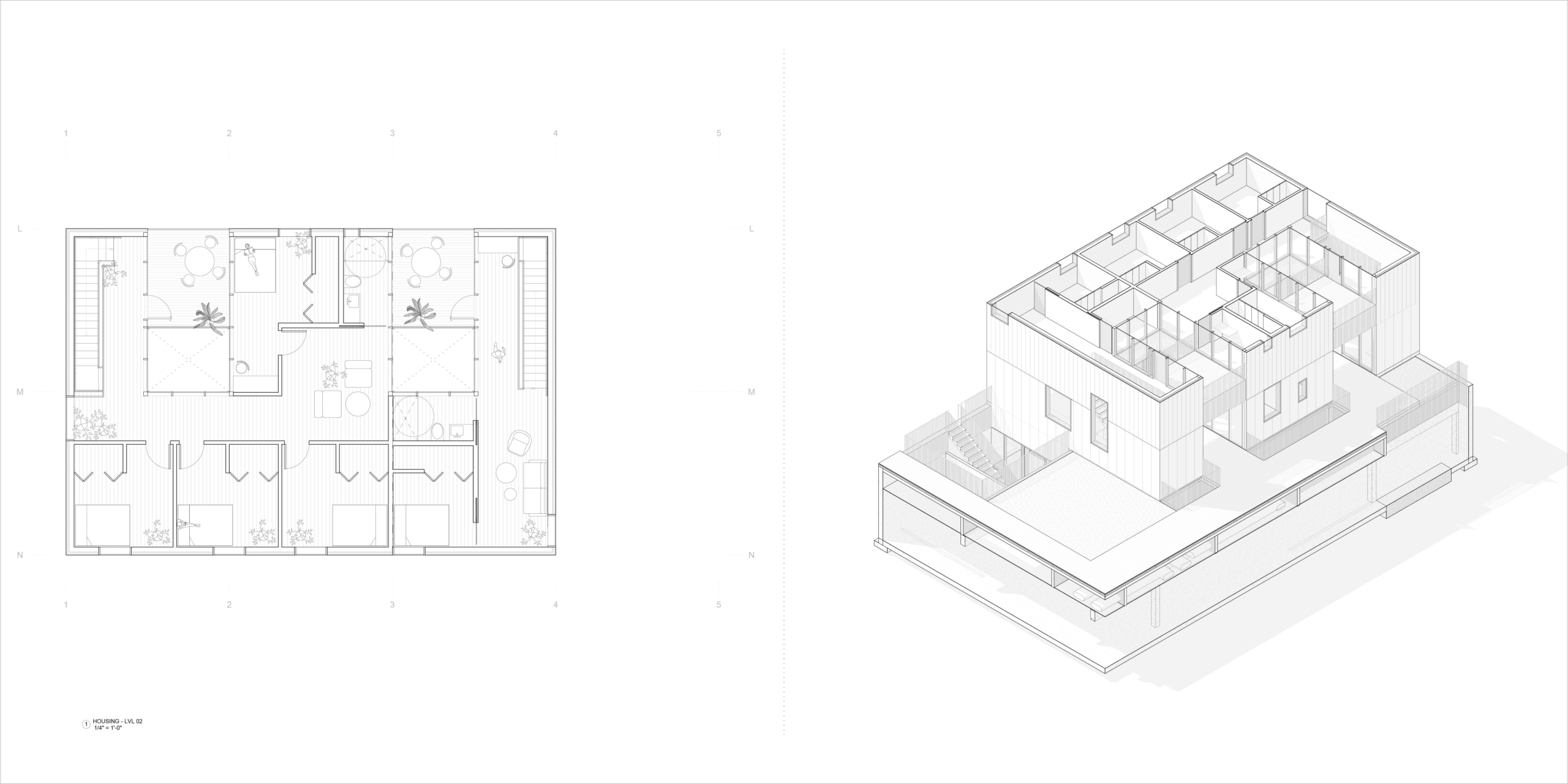

A New Prototype for Collective Housing by Juan Acosta and Gable Bostic, University of Texas at Austin, M.Arch ‘20

Advisor: Martin Haettasch / Course: Integrative Design Studio

Read more: https://soa.utexas.edu/work/new-prototype-collective-housing

Austin is a city that faces extreme housing pressures. This problem is framed almost exclusively in terms of supply and demand, and the related question of affordability. For architects, however, a more productive question is: Will this new quantity produce a new quality of housing?

How do we live in the city, how do we create individual and collective identity through architecture, and what are the urban consequences? This studio investigates new urban housing types, smaller than an apartment block yet larger and denser than a detached house. Critically assessing existing typologies, we ask the question: How can the comforts of the individual house be reconfigured to form new types of residential urban fabric beyond the entropy of tract housing or the formulaic denominator of “mixed-use.” The nature of the integrative design studio allowed for the testing of material systems and construction techniques that have long had an important economic and ecological impact.

“A New Prototype for Collective Housing” addresses collectivity in both a formal and social sense, existing between the commercial and residential scales present in Austin’s St. John neighborhood as it straddles the I-35 corridor; a normative American condition. A diversity of programs, and multigenerational living, create an inherently diverse community. Additionally, a courtyard typology is used to negotiate the spectrum of private and shared space. Volumes, comprising multiple housing units ranging from studio apartments to four bedrooms, penetrate a commercial plinth that circulates both residents and mechanical systems. The use of heavy timber ensures an equitable use of resources while imbuing the project with a familiar material character.

ELSEWHERE, OR ELSE WHERE? by Brenda (Bz) Zhang, University of California at Berkeley, M.Arch ’20

Advisors: Andrew Atwood and Neyran Turan

See more: https://www.brendazhang.com/#/elsewhere-or-else-where/

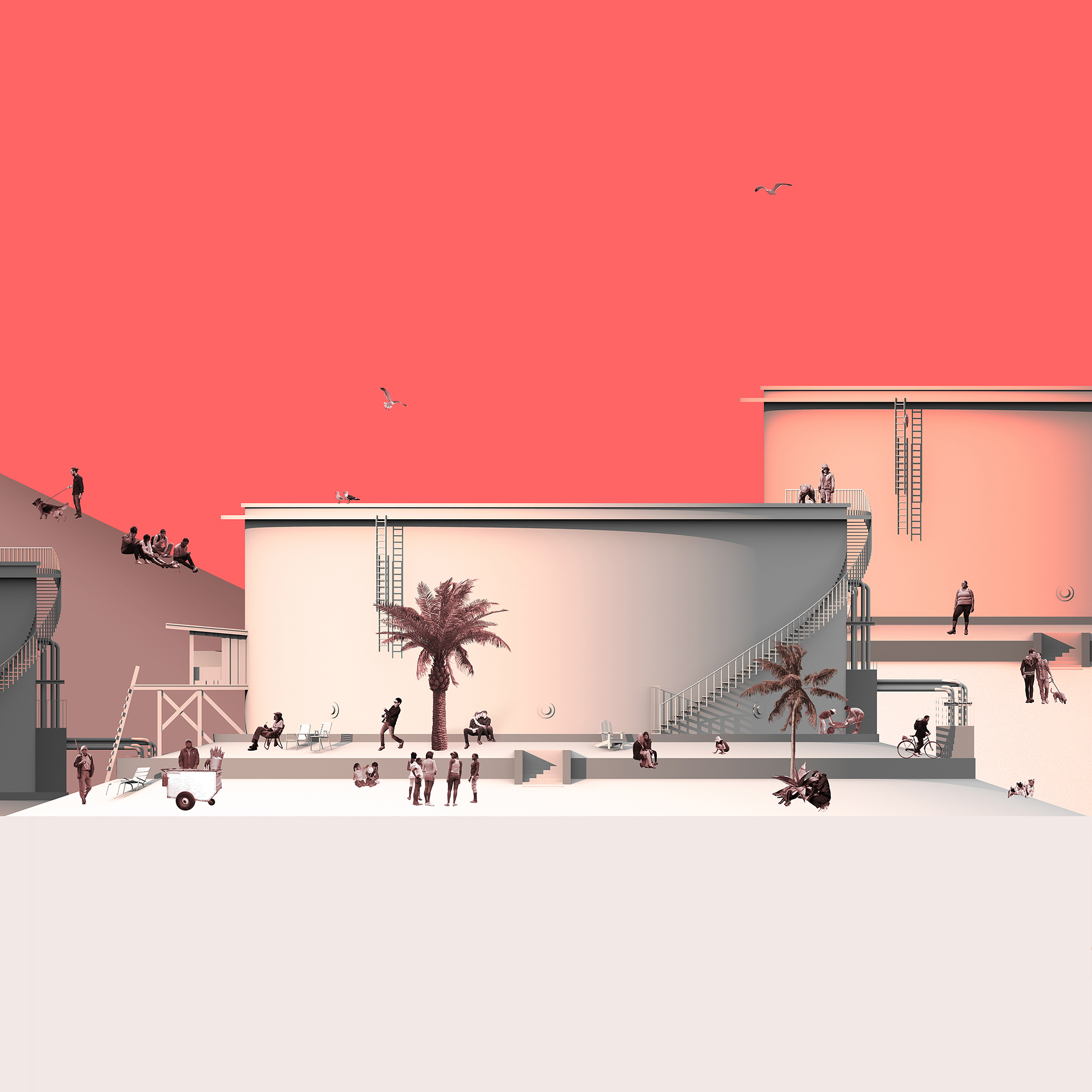

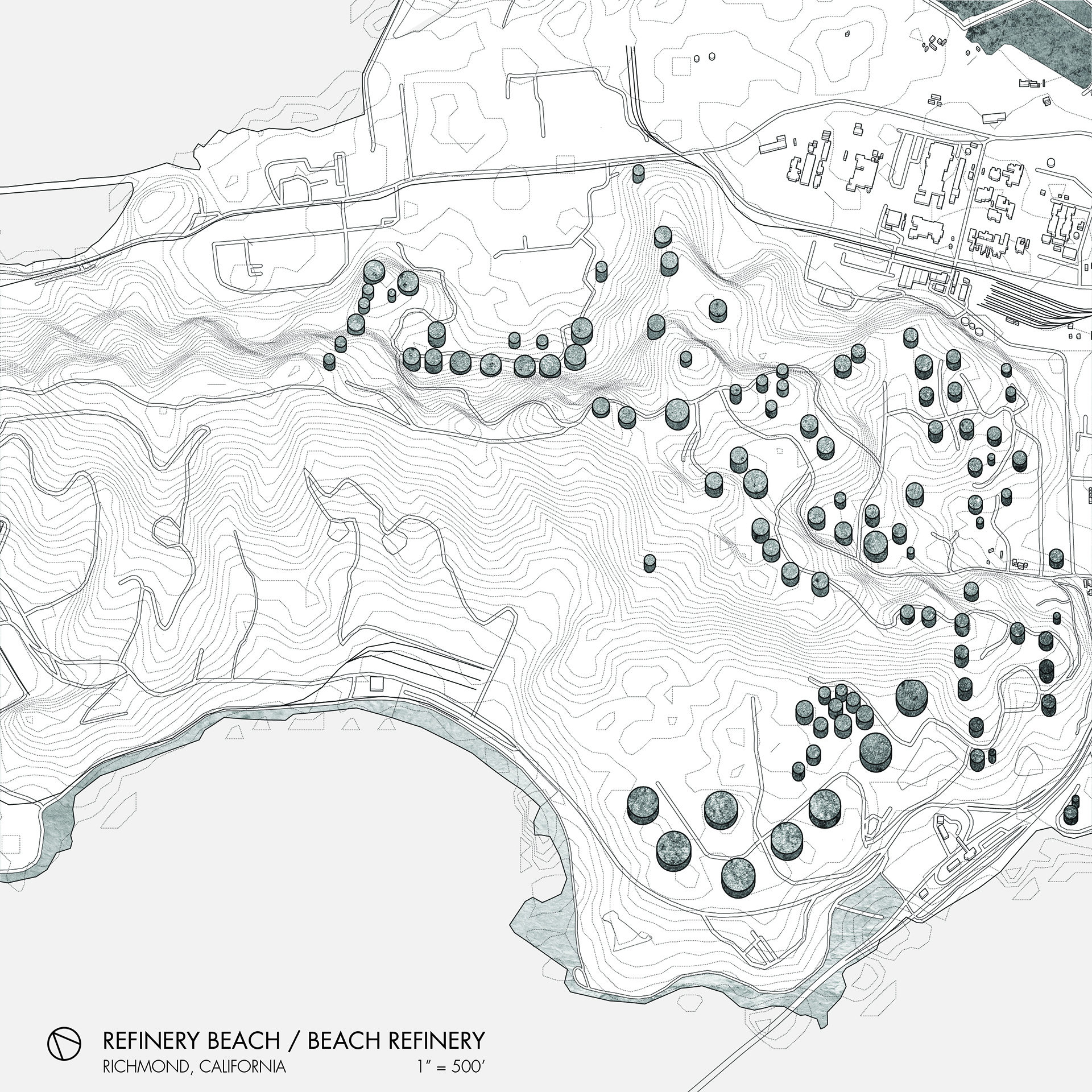

“ELSEWHERE, OR ELSE WHERE?” is an architectural fever dream about the San Francisco Bay Area. Beginning with the premise that two common ideas of Place—Home and Elsewhere—are no longer useful, the project wonders how disciplinary tools of architecture can be used to shape new stories about where we are.

For our purposes, “Home,” although primarily used to describe a place of domestic habitation, is also referring generally to a “familiar or usual setting,” as in home-base, home-court, home-page, and even home-button. As a counterpoint, Elsewhere shifts our attention “in or to another place,” away. This thesis is situated both in the literal spaces of Elsewhere and Home (landfills, houses, wilderness, base camps, wastelands, hometowns) and in their culturally constructed space (value-embedded narratives determining whether something belongs, and to whom). Since we construct both narratives through principles of exclusion, Elsewhere is a lot closer to Home than we say. These hybrid spaces—domestic and industrial, urban and hinterland, natural and built—are investigated as found conditions of the Anthropocene and potential sites for new understandings of Place.

Ultimately, this thesis attempts to challenge conventional notions of what architects could do with our existing skill sets, just by shifting our attention—Elsewhere. The sites shown here and the concerns they represent undeniably exist, but because of the ways Western architecture draws thick boundaries between and around them, they resist architectural focus—to our detriment.

In reworking the physical and cultural constructions of Homes and Elsewheres, architects are uniquely positioned to go beyond diagnostics in visualizing and designing how, where, and why we build. While this project looks specifically at two particular stories we tell about where we are, the overall objective is to provoke new approaches to how we construct Place—both physically and culturally—within or without our discipline.