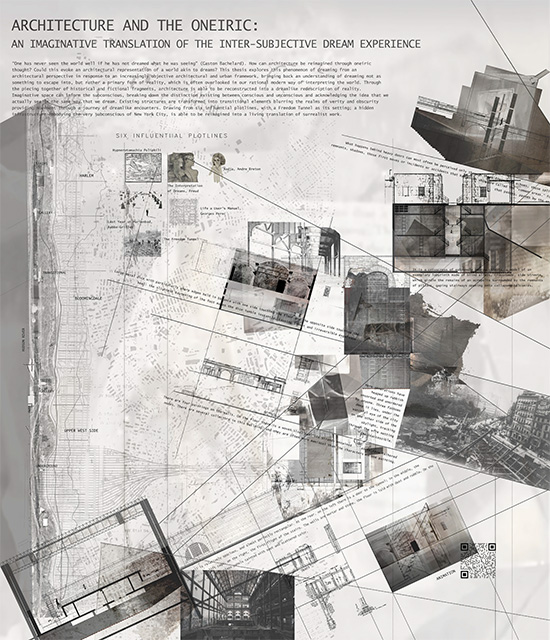

Architecture and the Oneiric: An Imaginative Translation of the Intersubjective Dream Experience by Amanda Scott, M.Arch ’22

North Dakota State University | Advisor: Stephen Wischer

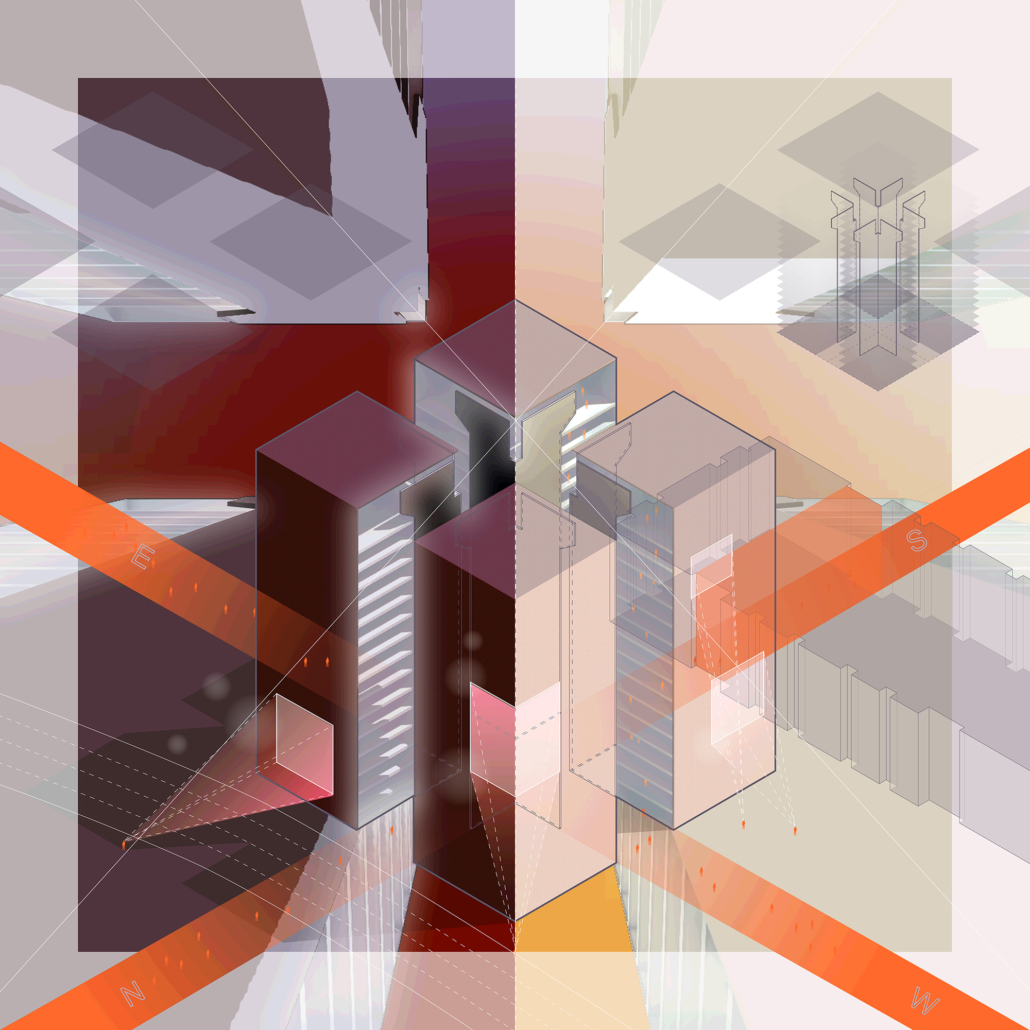

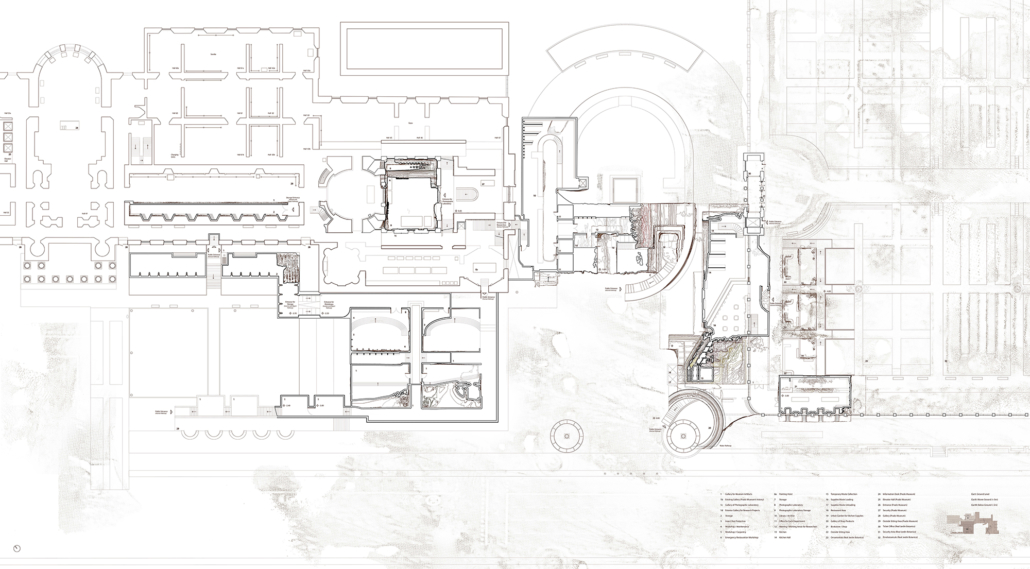

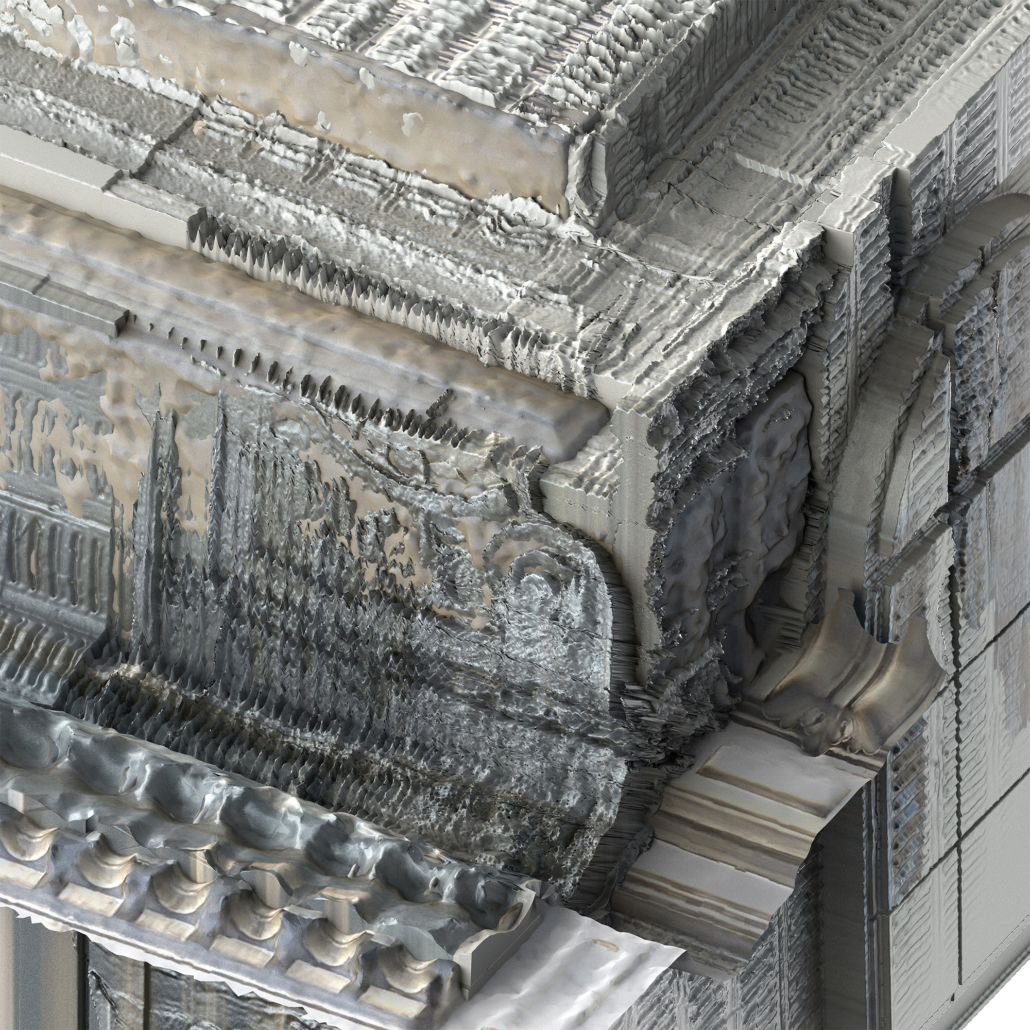

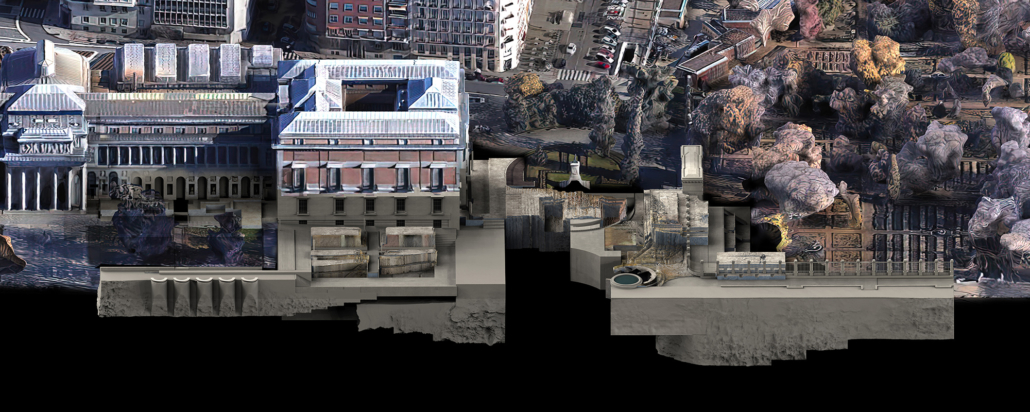

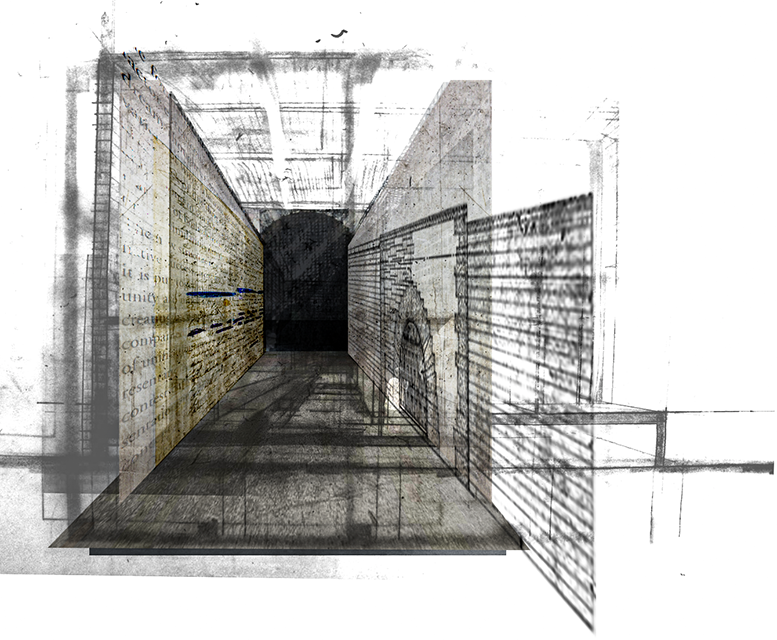

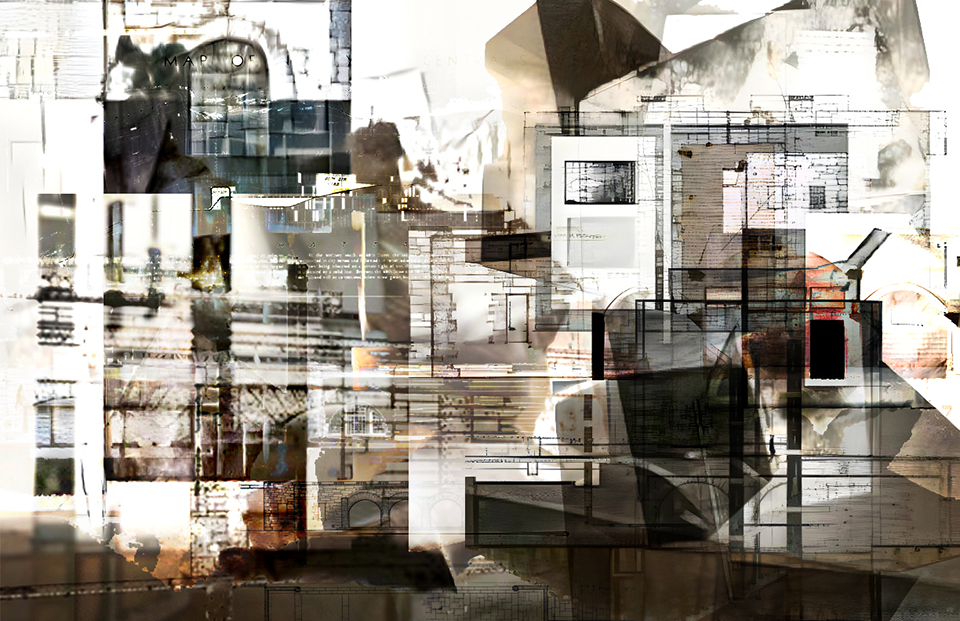

“One has never seen the world well if he has not dreamed what he was seeing” (Gaston Bachelard). How can architecture be reimagined through oneiric thought? Could this evoke an architectural representation akin to dreams?

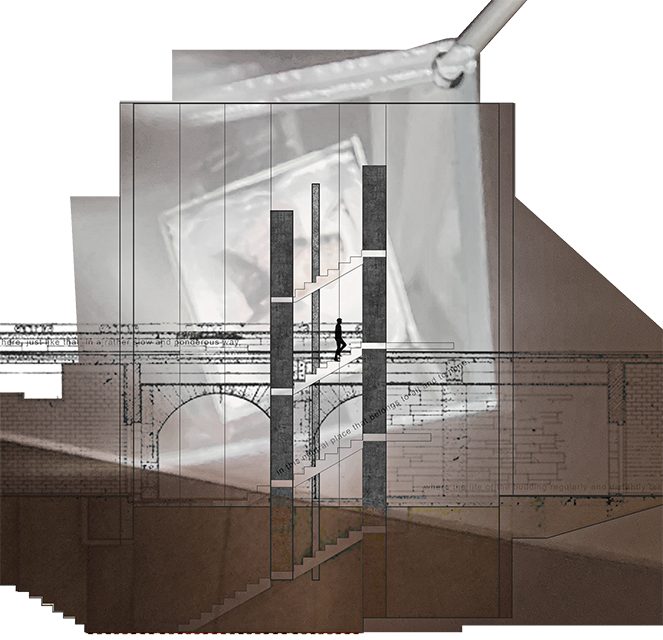

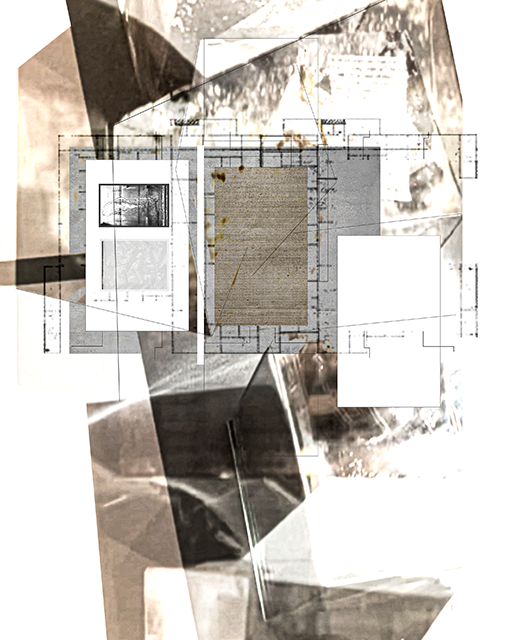

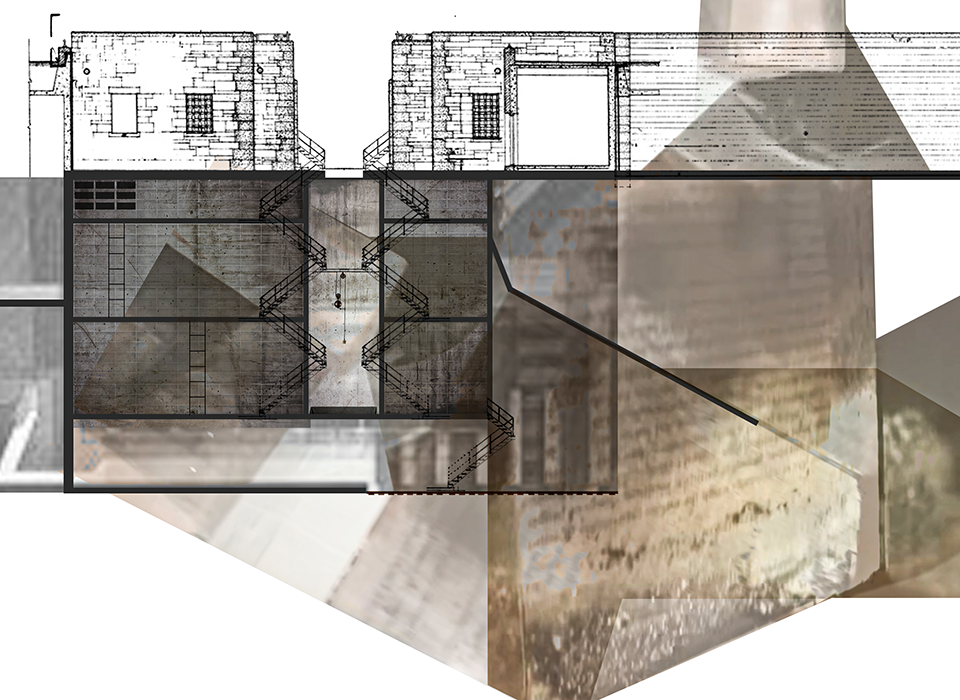

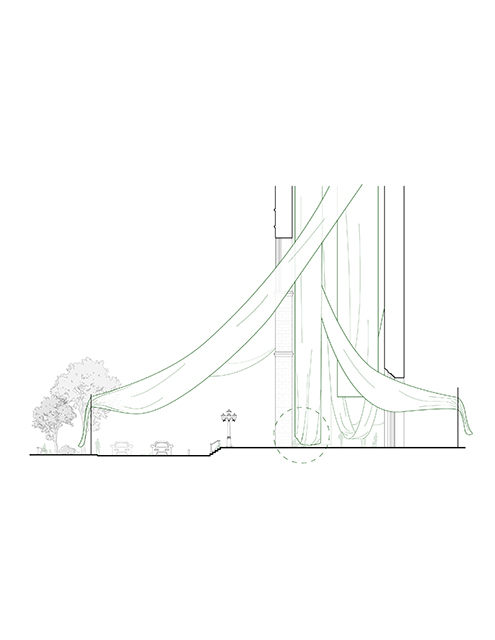

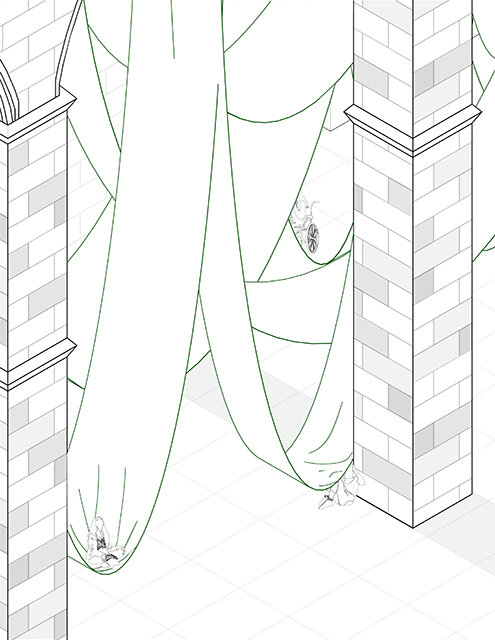

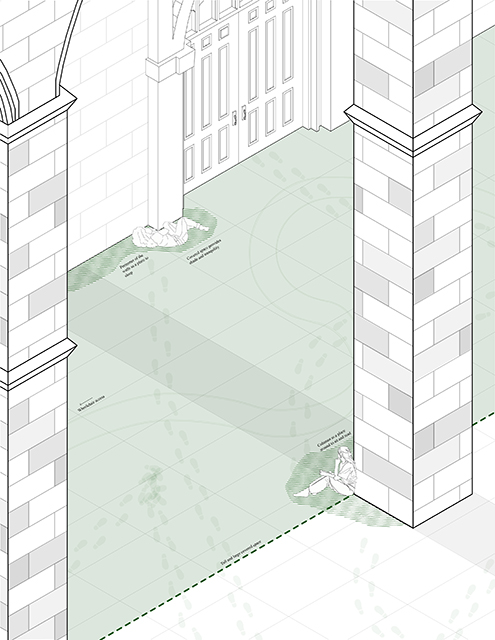

This thesis explores such questions by examining the phenomenon of dreaming from an embodied architectural perspective in response to an increasingly objective architectural framework. Drawing from psychological, philosophical, artistic, and mythical sources, we can examine aspects of dreaming not as something to escape into, but rather a primary form of reality, which is often overlooked in our rational, modern way of interpreting the world. Through the piecing together of historical and fictional fragments, architecture is reconstructed into a dreamlike re-description of reality that breaks down the distinction between real and imaginary, inside and outside, conscious and unconscious, acknowledging that we may actually see in the same way that we dream.

Walking along Freedom Tunnel in New York City, existing structures are transformed into transitional elements blurring realms of verity and obscurity, providing movement through a journey of dreamlike encounters. Drawing from six influential plotlines, with the hidden infrastructure of the tunnel as its setting; surrealist spaces are reimagined through a living translation of oneiric experience.

Instagram: @amandaa_scottt, @ndsu_sodaa

The Forever Home: Redefining Aging-In-Place by Laura Deacon, M.Arch ’22

University of British Columbia | Advisor: Inge Roecker

How do we house our aging population? This question – often overlooked, is one that requires an immediate solution. The population of individuals over 65 in Canada is projected to nearly double from 2020 to 2046, reaching 22% of the overall population. With this in mind, it is essential that architectural solutions are able to meet the dynamic needs of this aging demographic. The existing housing stock consist of reactive solutions, whereby individuals sequentially progress from one typology to another in accordance with their needs. This causes strain, confusion, and requires extensive support from the community as individuals orient and adapt to a new environment.

The primary objective of this thesis is to create an engaging environment that eliminates the burden of aging by allowing individuals to age-in-place throughout ones entire lifespan, in a vibrant community that facilitates architectural flexibility while simultaneously building resilience for future generations.

The Forever Home is a seven-story development situated in the heart of Yaletown, Downtown Vancouver, within close proximity to surrounding amenities and services. The proposed development features 196 adaptable modular units that allow for families to expand, contract, and divide at various stages of life, supplemented with a palliative care unit and guest suite located on each floor. Units are configured in a single-loaded corridor typology shaped around a central courtyard, which ensures adequate natural daylighting and cross ventilation is achieved. Residences are dichotomized into blocks consisting of eight units clustered around shared residential green space. Units also feature a semi-private buffer space between the public corridors and private units, which promotes socialization and neighborly connections amongst residents. Reverse community integration is achieved using a public grocery store, child care and adult daycare facility, restaurant, and smaller scale shops dispersed vertically throughout the building. In addition, residential amenities are also located on each floor. A clear wayfinding strategy assists residents to circumnavigate the building using a bright red bulkhead and a highly contrasting change in floor material, colour, and texture.

Instagram: @laurdeacon @ubcsala

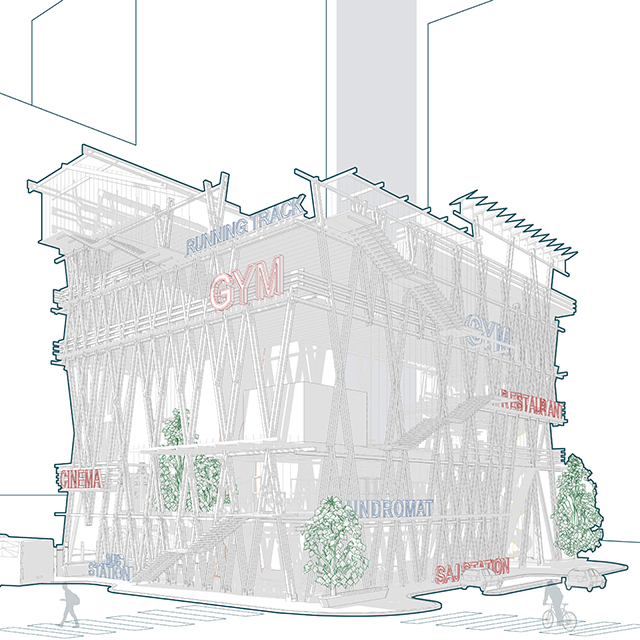

Changing Place: A Persuasive Multipurpose Park for Healthy Lifestyles by Cesar Tran, M.Arch ’22

NewSchool of Architecture and Design | Advisor: Michael Stepner, Kurt Hunker and Rebekka Morrison

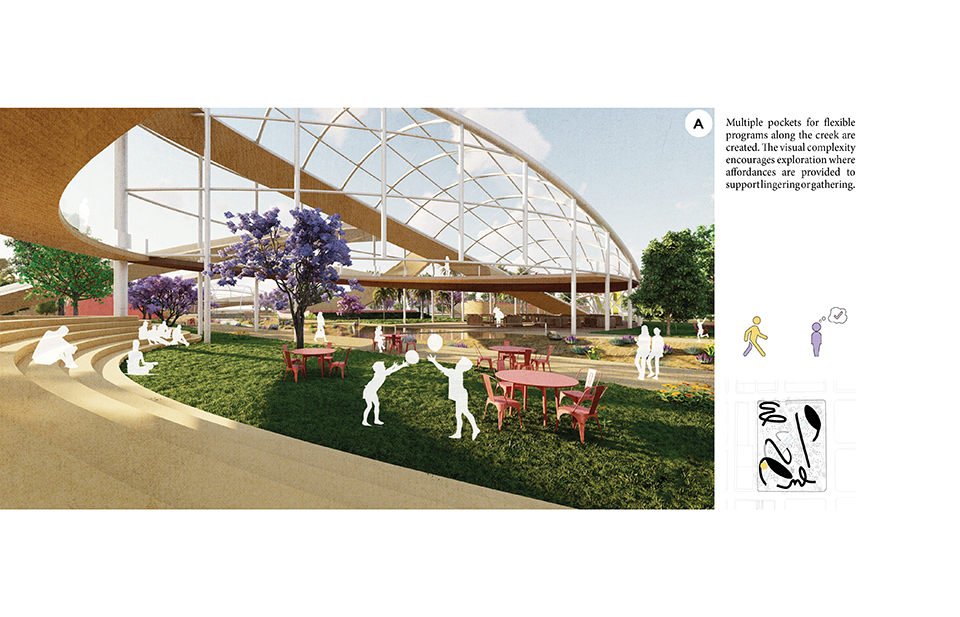

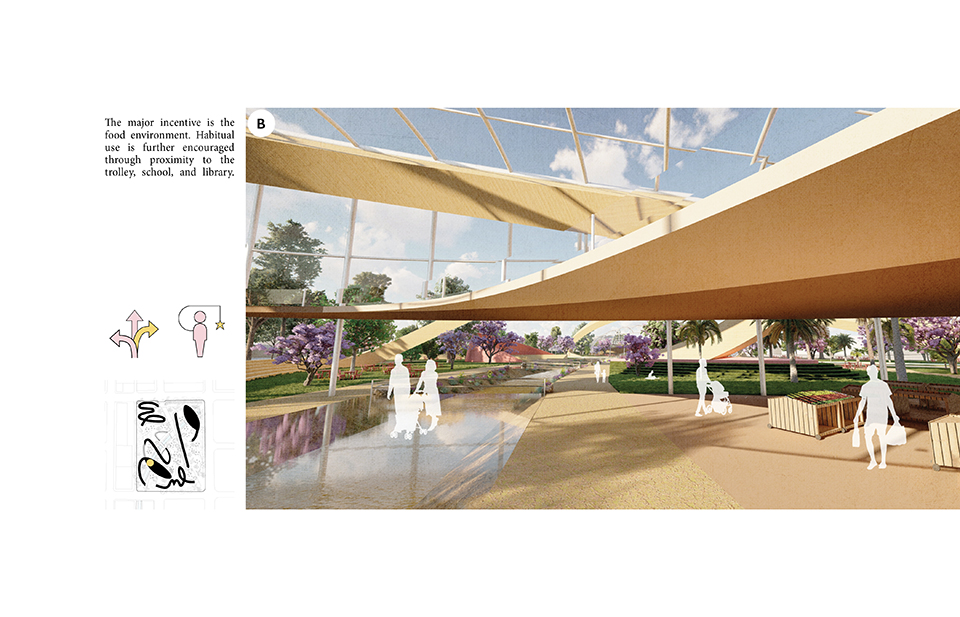

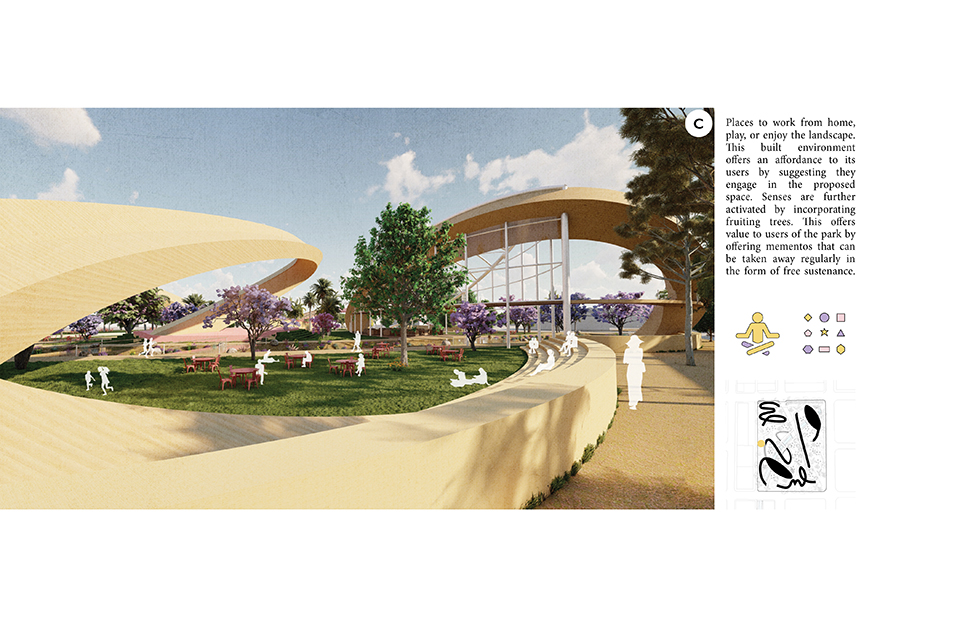

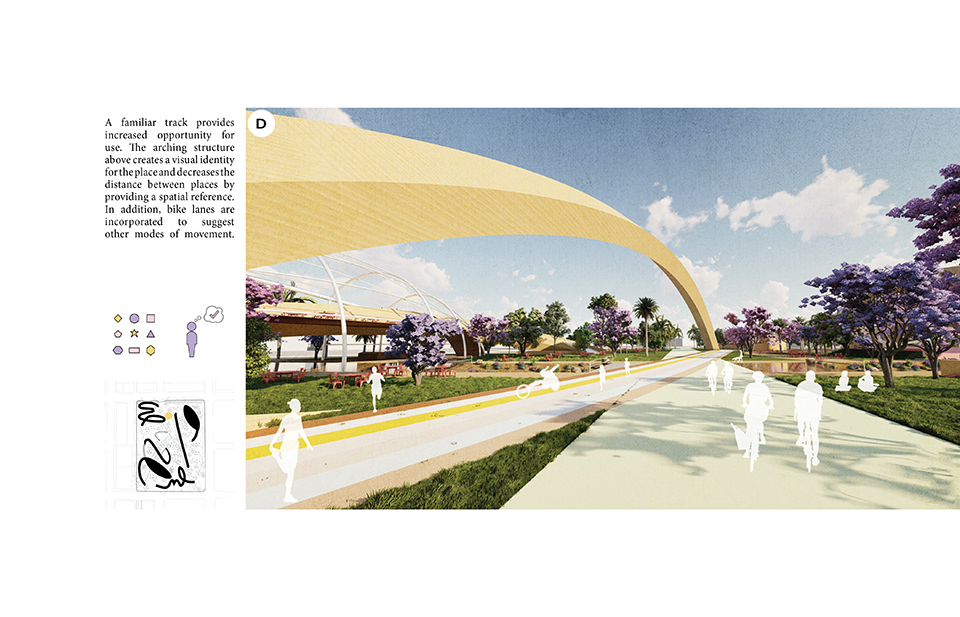

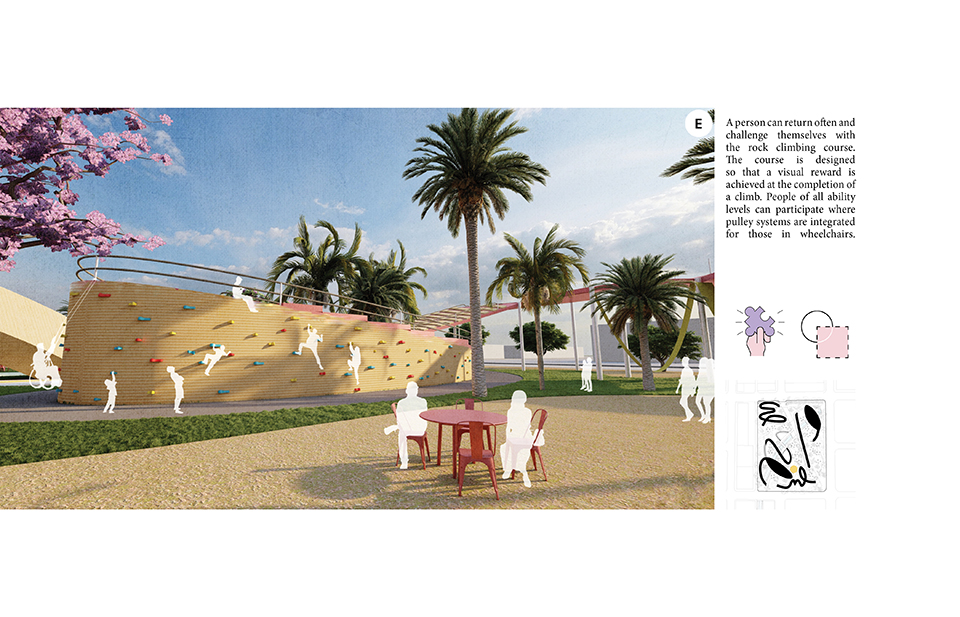

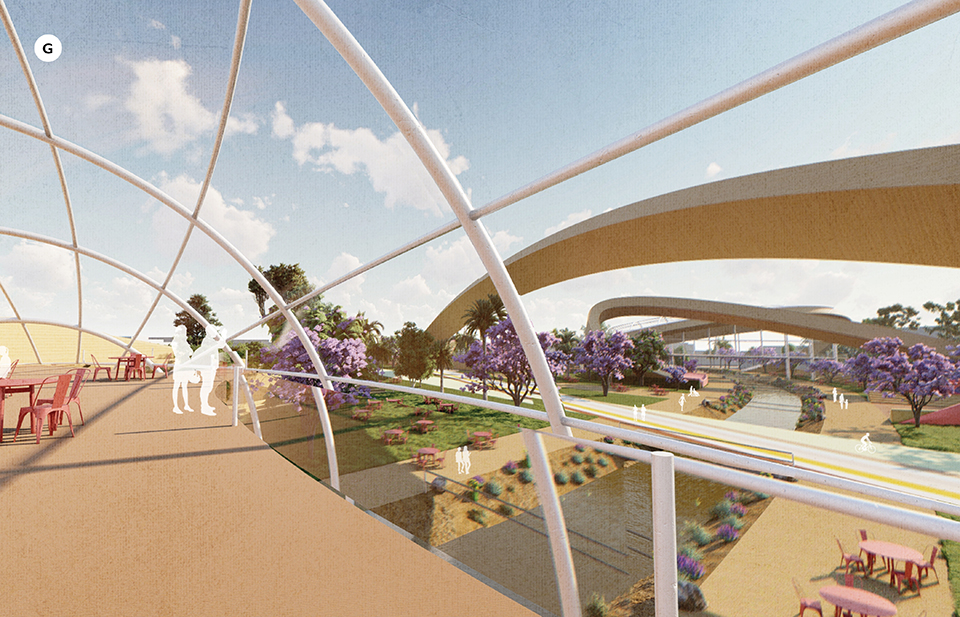

Sedentary lifestyles are becoming a standard that may lead to adverse health impacts over time. Surmounting these impacts include daily non-exercise physical activity (NEPA) to support mental, social, and physical health. In many scenarios, providing the space for NEPA may not be enough to encourage participation. Built environment designers can combat this by incorporating persuasive psychological techniques for physical activity. These methods are typically found to stimulate consumerism and addiction, therefore, this thesis reclaims these methods to promote wellness through the suggestion of healthy lifestyles.

A literature review was conducted to better understand the components of a healthy life, the types of psychology employed for increased engagement, and the different architectural environments that encourage NEPA with or without intention. The review culminated with the creation of a framework consisting of nine strategies that can be considered in architectural design for habitual NEPA. Case studies were then analyzed to better understand the usage of the strategies in today’s built environment. The results were then utilized and demonstrated in a theoretical project to encourage NEPA in National City, CA which is known to have high rates of coronary heart disease and stroke.

A multipurpose park with flexible food markets and co-working spaces was designed to attract community members to participate in NEPA. The primary reason to journey here is to satisfy a person’s basic needs, sustenance. Pairing this program with multiple incentives associated with stress relief and play creates convenience for users which can lead to a routine over time. This example supports the thesis through framework application and exhibits one of the ways the built environment can encourage healthy routines through the power of persuasion.

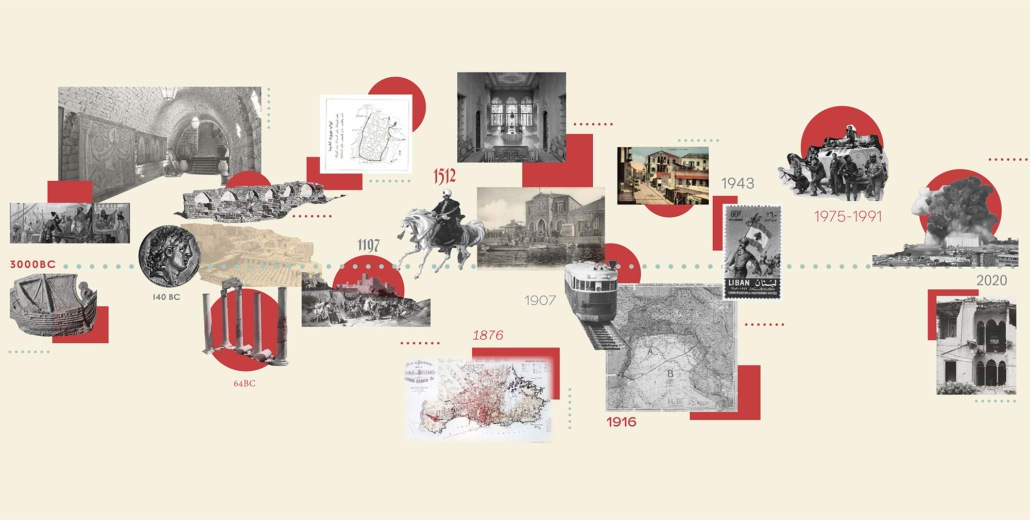

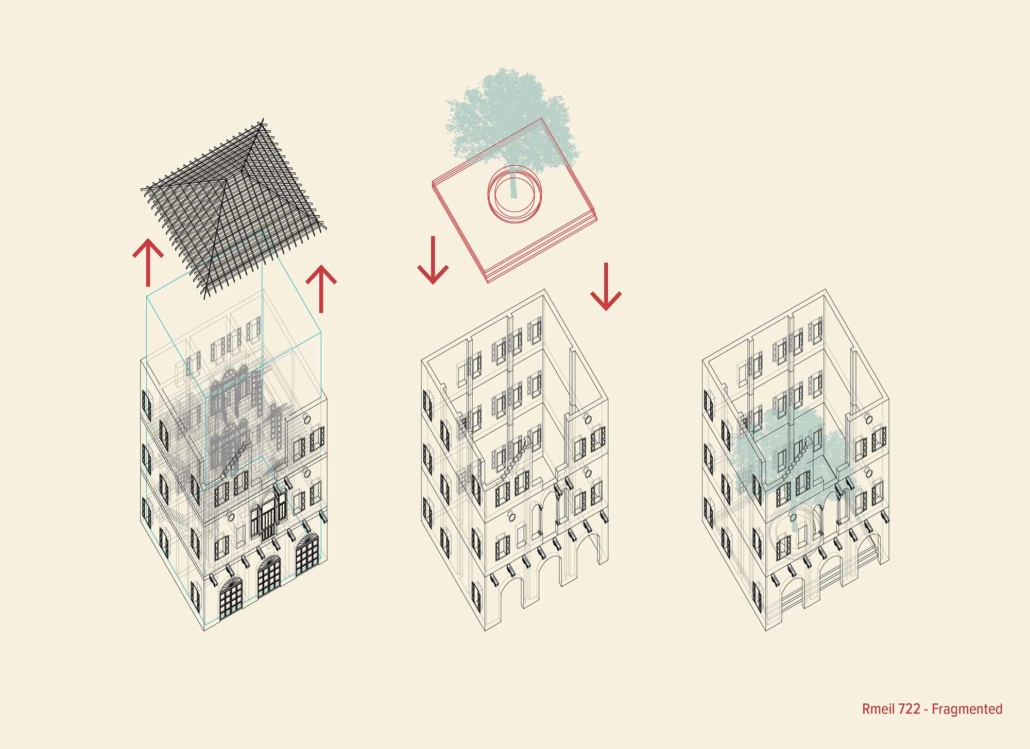

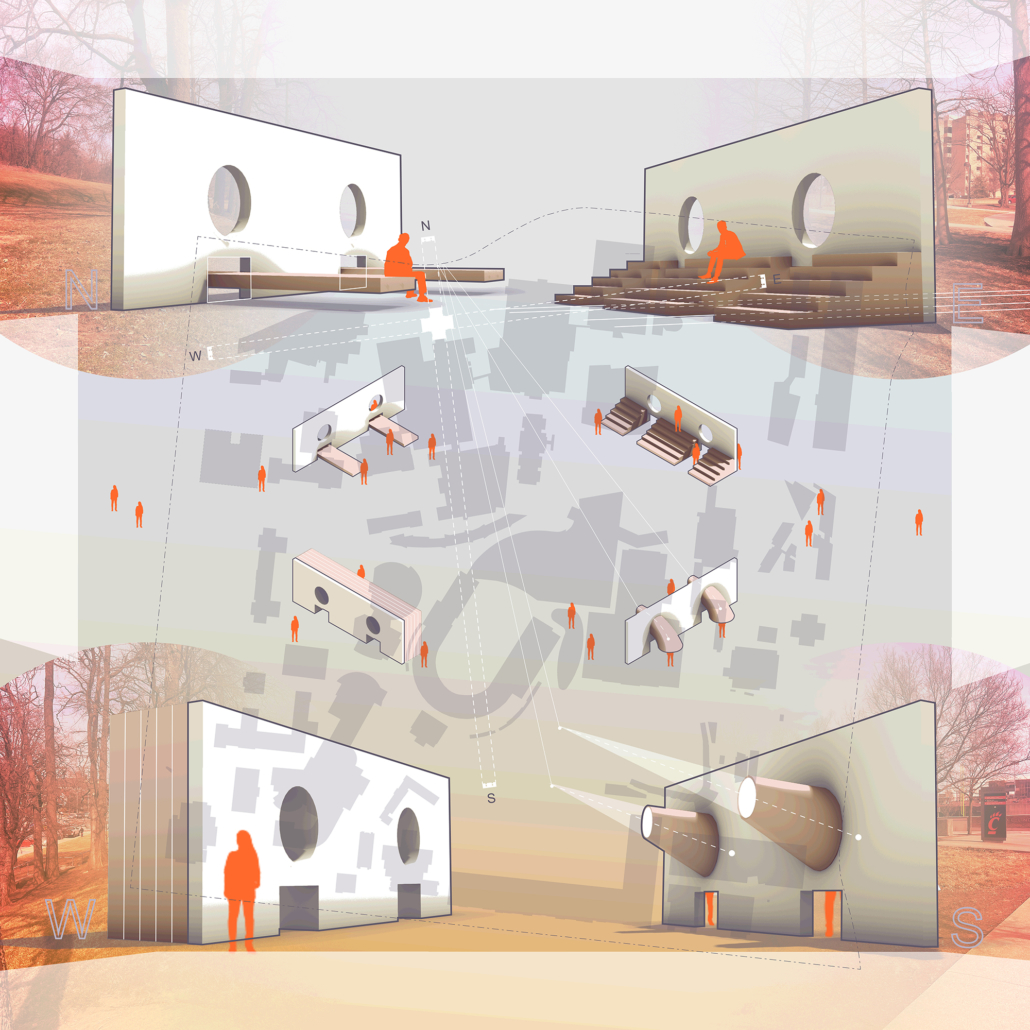

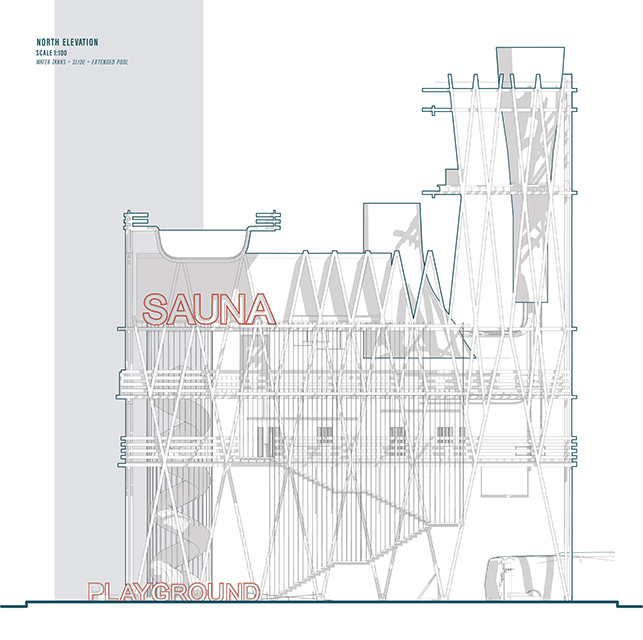

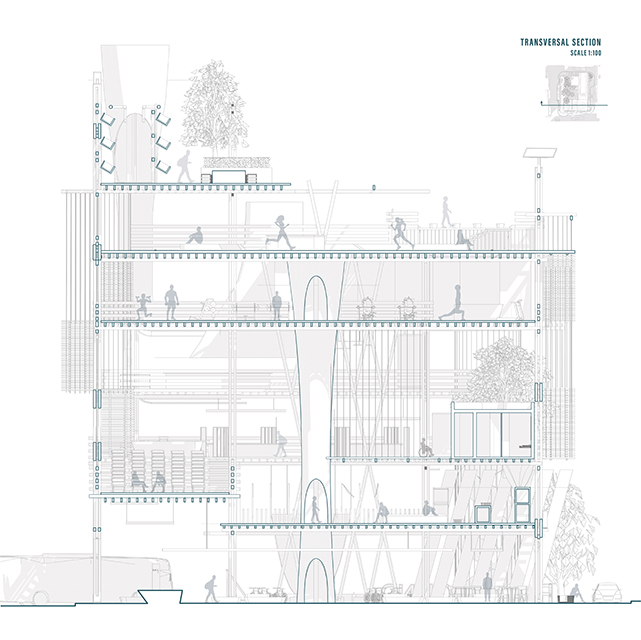

[A]WAITING TO DIFFUSE by Joseph Chalhoub, B.Arch ’22

American University of Beirut | Advisor: Carla Aramouny

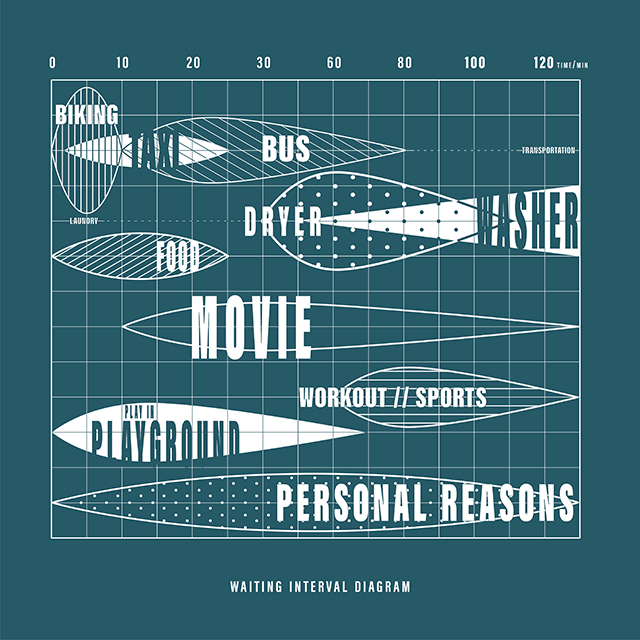

When starting any design project, we, as architects, always start by analyzing the site, mapping out conditions and studying human behavior in order to better understand how we can intervene. However, while we look at walking patterns, climatic conditions and many other aspects, we are always neglecting one very important factor: WAITING.

During the most recent economic and infrastructural collapse Lebanon has been going through, the project zoomed into ‘waiting’ as a research topic. At the time, waiting was something happening on various scales, from existential waiting to waiting in line for gas.

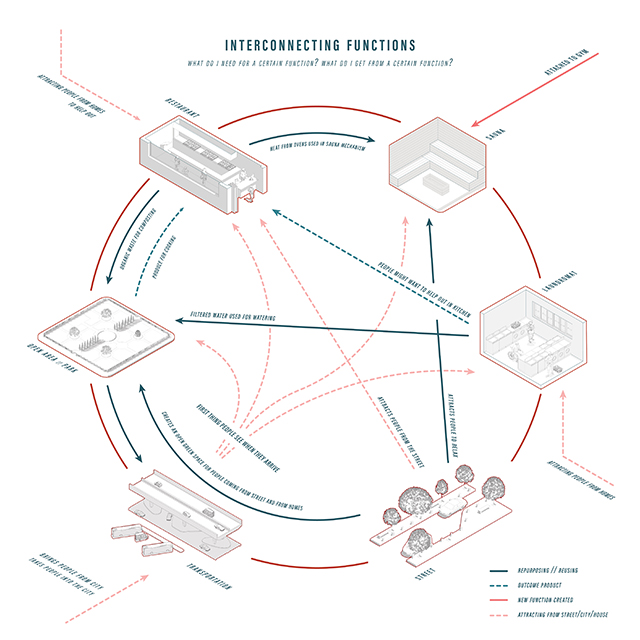

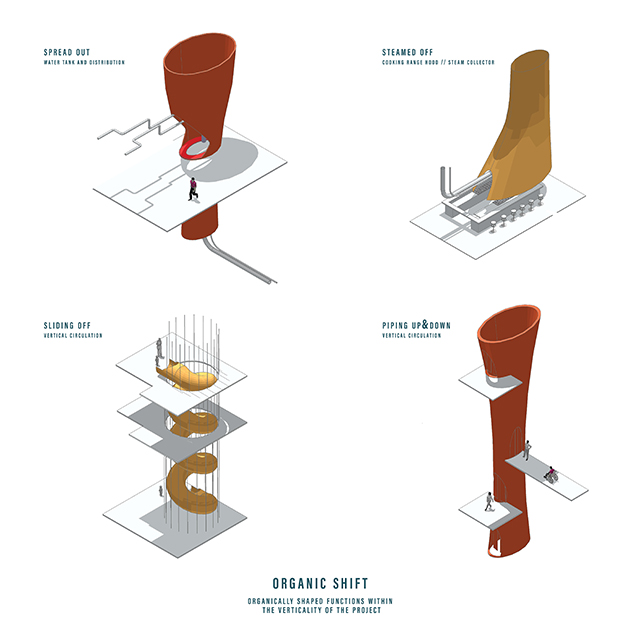

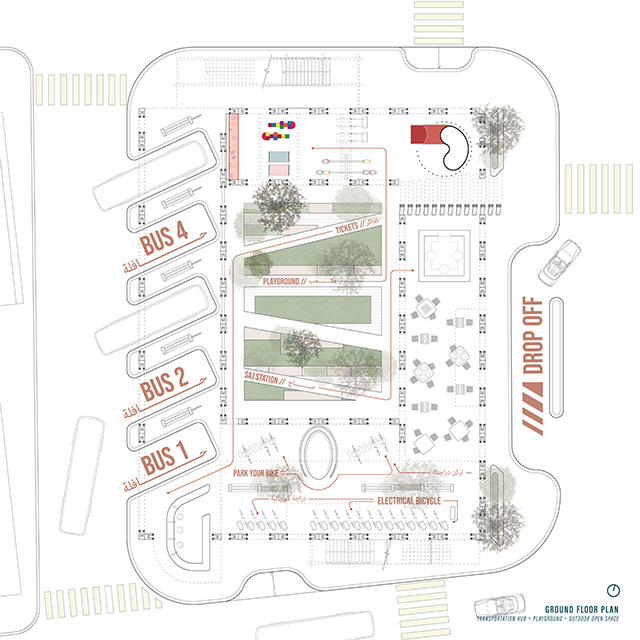

With a blend of anthropological research, design experiments, and research in the arts, architecture, and placemaking, the project tackles how the notion of waiting can be repurposed, reused and activated to make the most out of this urban condition. In fact, the project presents a set of functions tailored to the needs of the neighborhood and encourages users to participate and help out in the different activities. Here lies the notion of interconnected functions. By taking the waiting out of certain functions, we can repurpose them towards others and so on and so forth.

This type of adaptive reuse can feed back into the architectural intervention in more than one way. Waiting would be recycled by giving the individual multiple outlets for their time. The project presents a new kind of “Waiting Typology” that can possibly be adapted and integrated into different neighborhoods in order to answer the need of the person waiting and change depending on the site specifications. Waiting then becomes something that we can use within our research, something that is regenerative, something that is awaiting to be diffused.

Instagram: @joeych99, @ard_aub

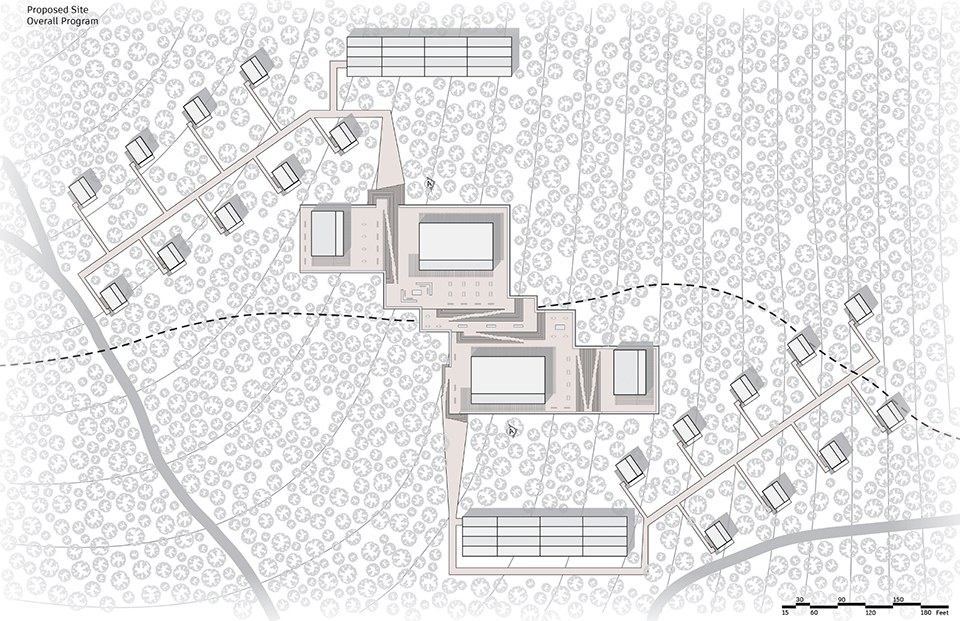

Wellness in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ): Connecting with Culture and the Environment by Briana Pereira, B.Arch ’22

New York Institute of Technology | Advisor: Dongsei Kim

The Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea is one of the most militarized areas in the world. Protected from urbanization for the last 69 years, the DMZ has become an involuntary park for flourishing flora and fauna with minimal human intervention.

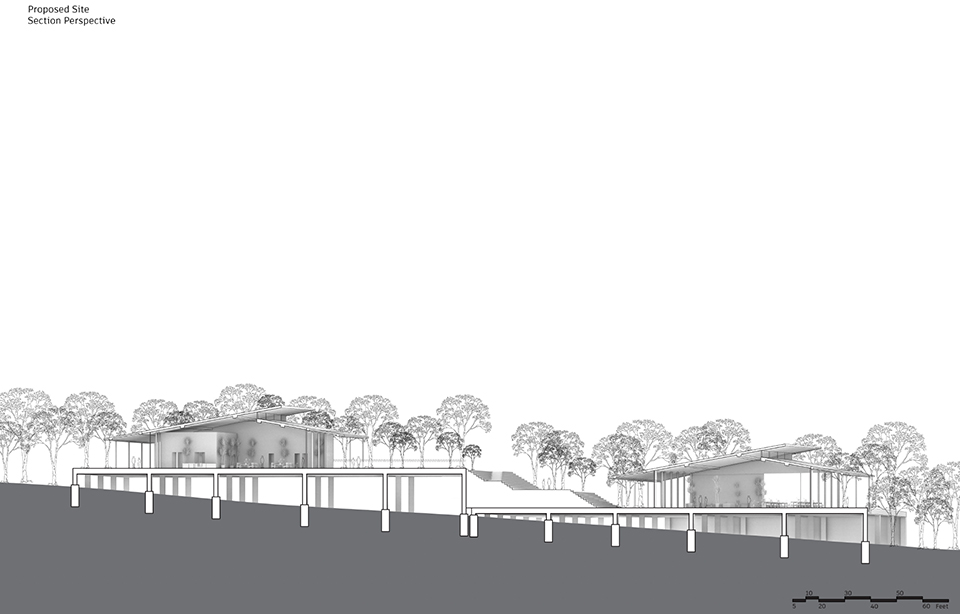

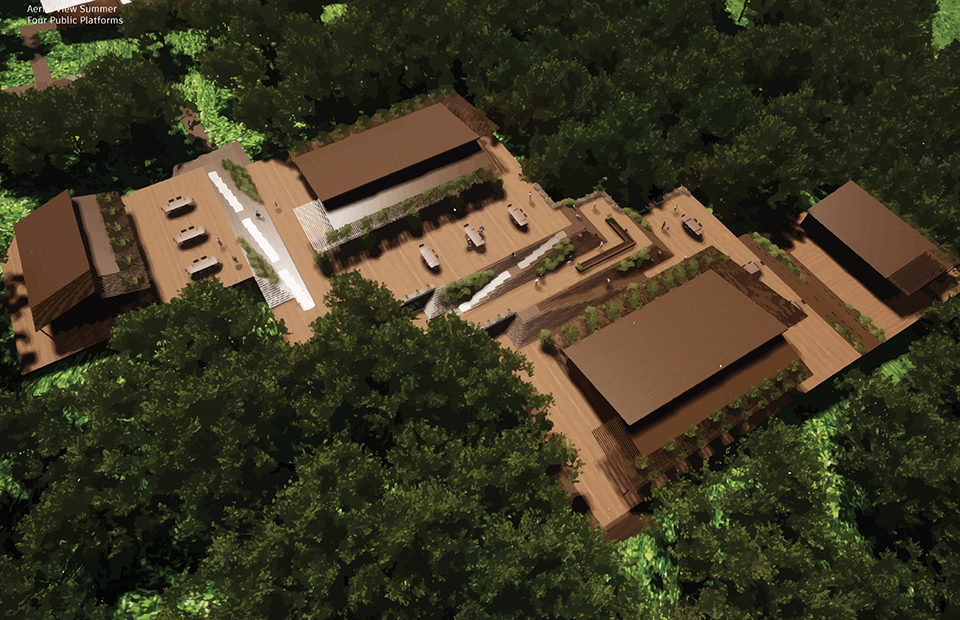

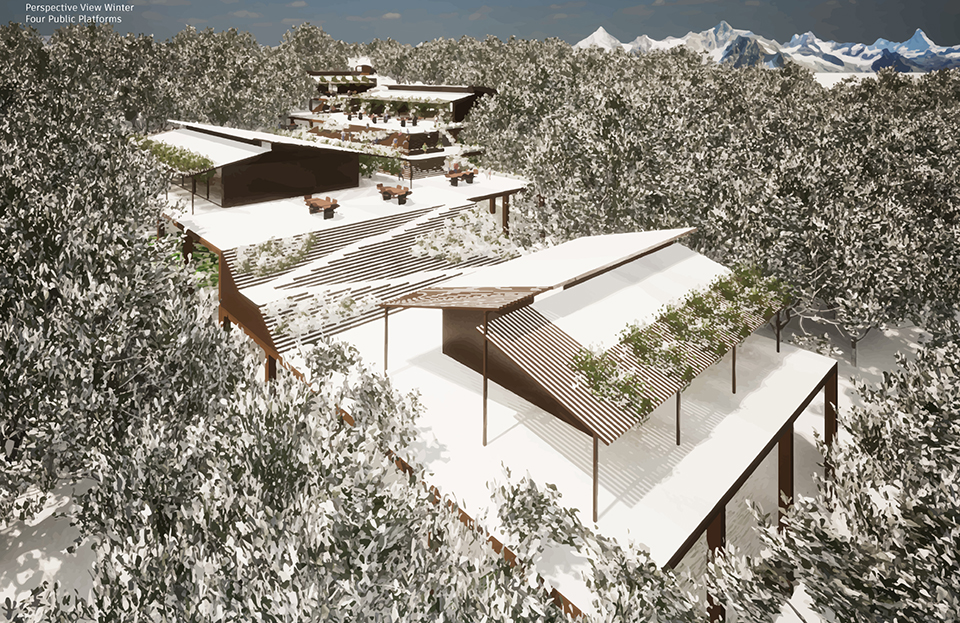

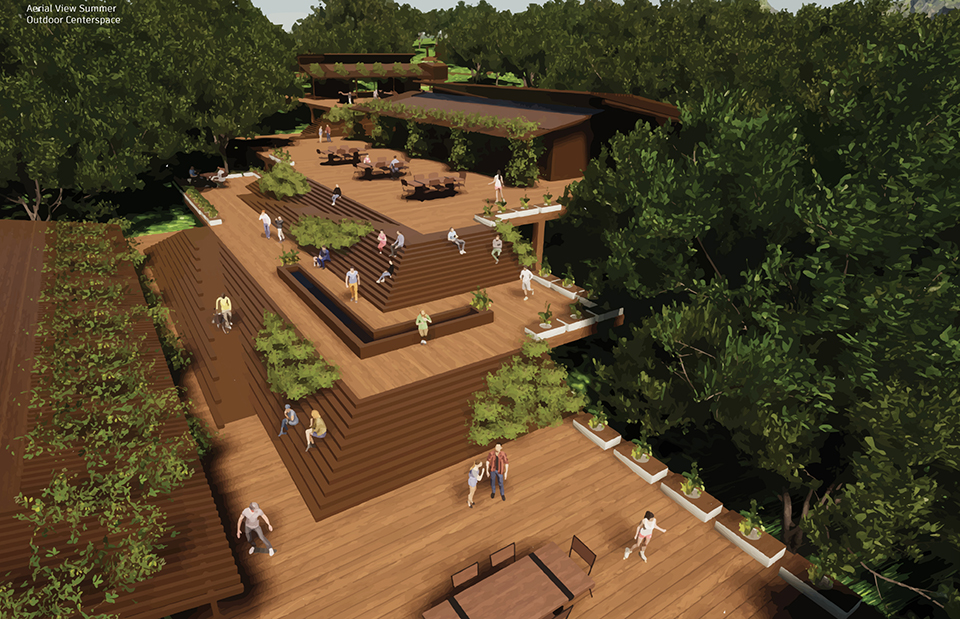

This project takes advantage of this unique condition and nature’s healing ability to house a new mental health wellness center within the DMZ open to both Koreans and foreigners. Located on the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) within the DMZ, the project is integrated into the cascading landscape in the heavily forested eastern region of the DMZ. Immersed in nature, visitors engage the natural environment through the project’s landscape and architectural spaces to recuperate and improve their mental health.

In addition, visitors engage in traditional Korean cooking and pottery, tea ceremonies, meditation, yoga, reading, walking, and other reflective programs and activities to improve their mental health. Here architecture becomes a container for shared Korean cultures. Further, the project benefits visitors’ mental wellness through how the architecture frames the immediate mountain ranges’ beauty and how it captures the Korean peninsula’s four distinct seasons.

Instagram: @briana_pereira_, @dongsei.kim

Wood is Good: Informing Wood Architecture Through the Investigation of Craft in Furniture by Daniel Rodrigues, M.Arch ’22

Laurentian University | Advisor: Randall Kober

The act of craftsmanship, specifically woodworking, gives a sense of accomplishment that is therapeutic. Improving the well being of someone who is part of this maker culture yields positive benefits to the state of their mental health from making as a form of therapy in a nonclinical manner.

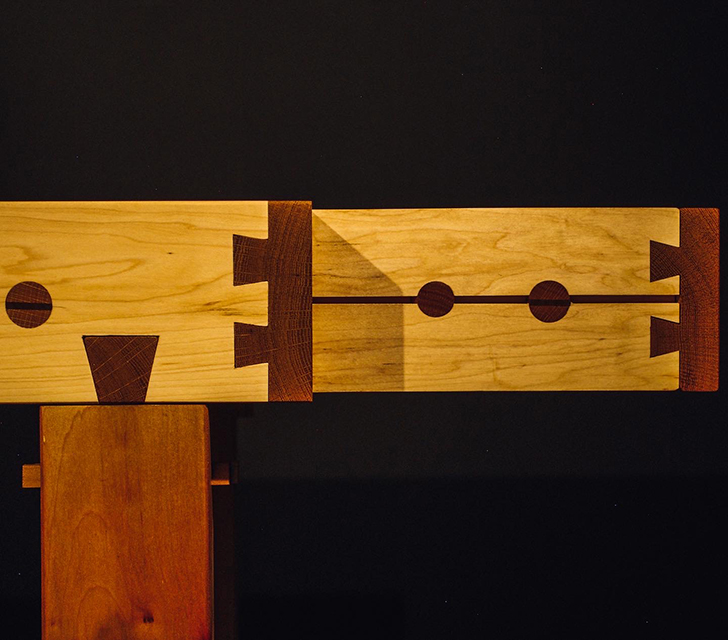

The final project will be a community oriented woodshop, located in the downtown of Sudbury, Ontario. This is a methodology driven thesis, where the primary method is learning through making; specifically, the design and construction of an intricate workbench as the most important experiment.

The focus of the research is to investigate how the design and craft of furniture can inspire and inform contemporary wood architecture at varying scales. This architecture will be didactic in nature, exemplifying craft through the tectonic connections of complex wood joints that embody the inherit potential of wood as a building material.

Instagram: @danielrodrigues343, @randallkober

I WENT FOR A WALK Observations, Reflections, and Imaginings upon Montréal’s Everyday Thresholds by Shane Villeneuve, M.Arch ’22

Carleton University | Advisor: Piper Bernbaum

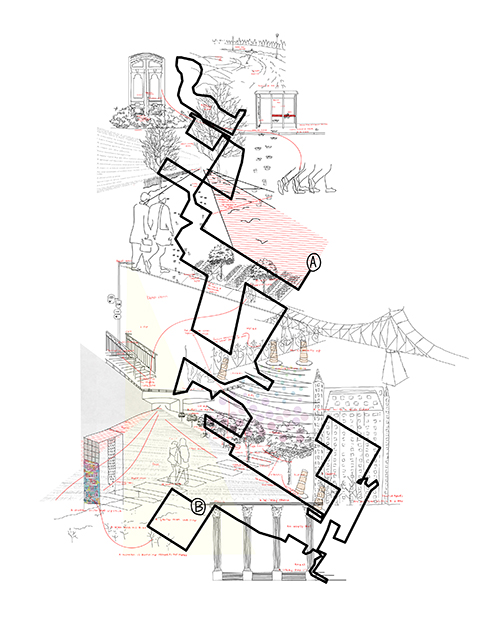

I went for a walk.

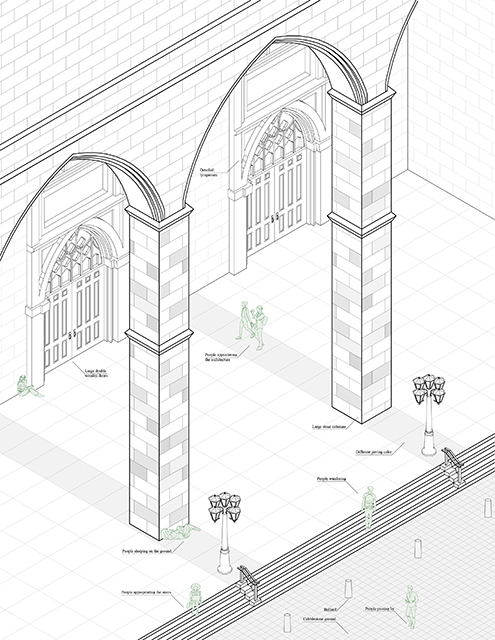

Borrowing from the methods of The Situationist Movement and setting out to explore “the in-betweenness” of the city of Montréal, this thesis engages in a series of personal “drifts.” The moments explored in the work are liminal spaces – most commonly defined in architectural practice as thresholds. A threshold is a space of anticipation existing at the convergence between different spatial conditions. It possesses such depth that it may elicit a profound stimulation of the senses in the human body. Perception is personal and tied to our own needs, desires, and experiences; a wanderer may perceive a threshold in the public sphere of the city as monumental or banal depending on their subjective and personal relationship with it.

Therefore, this thesis attempts to explore and question the most mundane experiences of the everyday thresholds encountered in the drifts and consider what extraordinary value is found in some of the most overlooked spaces. How do we slow down? How do we feel safe? How do we learn from the way space is used and appropriated, and the complexity of how it serves the city through its everydayness instead of only considering it for how it was originally designed? Thresholds become places of crossing over, of repose, of exchange and of transition, and become a space where the public can engage in the architecture of the city in the in-betweenness. Through “drifting”, this thesis eventually becomes a space to imagine new threshold conditions revealing and amplifying the potential that these moments offer to everyday citizens.

Instagram: @villeneuves @piperb @carleton_architecture

Stay tuned for Part VIII of the Student Showcase!